A Metaphysical Nightmare: Brian Moore’s Cold Heaven

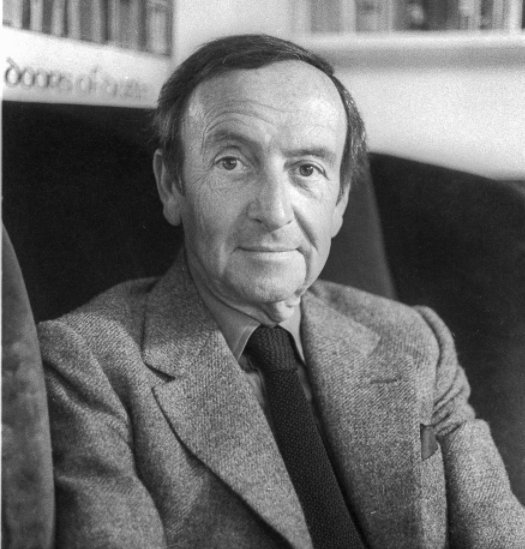

The Irish writer Brian Moore, who died in 1999 (he pronounced his first name in the Irish fashion — Bree-an) was one of the most interesting novelists of his time, at least based on the four books of his that I’ve read, all of which deal with areas where the supernatural, the philosophical, and the theological intersect and blur into each other.

Catholics (1972) is set in the near future after a hypothetical Fourth Vatican Council has banned private confession, clerical garb, and the Latin mass, while the fictitious Pope of the novel is engaged in negotiating a formal merger of Roman Catholicism and Buddhism, radical changes that are resisted by a handful of monks living on a small island off the coast of Ireland. In The Great Victorian Collection (1975), a scholar dreams of a fabulous collection of Victorian artifacts, and when he wakes up, it has actually appeared in the parking lot outside his California motel room. Who will believe such a thing? Can he believe it himself? Black Robe (1985) is a painstakingly detailed — and bracingly unsentimental — historical novel about the material and spiritual struggles of a Jesuit missionary to the Hurons in seventeenth century Canada.

Cold Heaven (1983) was the first Moore novel I read. That was over thirty years ago, and though the details faded over the decades, I retained a fairly strong memory of the theme and overall shape of the story. The impression that remained the strongest, however, was a feeling of general dislike. Because I very much enjoyed the subsequent Moore novels I read, I’ve often wondered whether my tepid response to Cold Heaven was my own fault; perhaps I just didn’t know how to read the book all those years ago. It was in this frame of mind that I recently reread the novel, reconfirming some of my original impressions and altering others.

Issues of faith and belief are central to all four of these books. Moore was raised a Catholic (and not just any Catholic — an Irish Catholic), though by the time he began his writing career he was no longer a believer. Though faith is a closed issue for most believers and non-believers alike — they’ve just come to different conclusions — for Moore the question is far from settled. Despite his rejection of his religious upbringing, in his books dealing with faith isn’t like picking up a lifeless broom handle — it’s like grabbing a snake. You can never be sure you’ve got a secure hold on it, and you have to adjust your grip constantly, because the thing you’re dealing with is alive, with a will of its own.

Before going any farther, a disclaimer — I am not a Roman Catholic, but I am a Christian, and though I am unable to entirely set aside my philosophical and theological convictions when I read a piece of fiction, I do make a good faith effort to take a writer’s work on his or her own terms. Given the subject of this book, I tried especially hard to assume as “neutral” a position as possible. I will say that Moore didn’t make that easy, which was probably his intention.

Cold Heaven is told (almost) entirely from the point of view of a young American woman in her mid-twenties named Marie Davenport. When the story begins, Marie is on vacation with her physician husband, Alex, in the south of France, where he is attending a medical convention. Marie has decided to leave Alex, an arrogant, controlling, selfish man, for her lover Daniel, whom she has secretly been having an affair with for over a year. Marie hasn’t yet summoned the courage to tell Alex this, however.

Before Marie can bring herself to confront her husband with her decision, Alex is struck by a motor boat while swimming in the Mediterranean and suffers a skull fracture. He is taken to a hospital, where he dies without ever regaining consciousness.

Things immediately shift from the tragic to the bizarre and inexplicable when Alex’s body disappears from the hospital. Has it just been “misplaced”, or is there something else going on? Marie begins to think the latter when she checks her hotel room and discovers that Alex’s clothing is gone and that someone has used his airline ticket to return to the states. Marie follows and catches up with this person, who turns out to be Alex, very much alive — sort of.

What happened? All Alex knows is that he woke up in the hospital morgue; confused and seized by panic, he fled the hospital and the country. When Marie finds him, he is wildly unstable; sometimes he seems almost normal, but most of the time he swings between combative agitation, and most frightening to Marie, a dull, glassy-eyed affectlessness when he seems little more than a zombie. Physically, his vital signs also go through extreme fluctuations; at times, his pulse and temperature readings are so low as to literally be impossible, and sometimes he seems to again be dead. Alex is apparently helplessly suspended between life and death.

Unwilling to abandon him in this condition, Marie wonders whether her husband is being used to punish her for something that happened a year before, and it is this mysterious event and Marie’s response to it that form the crux of the novel.

Exactly one year before Alex’s accident, Marie had been in Carmel, California for a tryst with Daniel. She had been taking a solitary stroll along the cliffs by the ocean when the figure of a young girl appeared lower down the cliff side, in a spot where it would have been virtually impossible for a person to be. Bathed in an eerie, unearthly light, the girl called Marie by name and told her, “I am your mother. I am the Virgin Immaculate.” She also instructed Marie to tell the priests of this encounter, because that spot must become “a place of pilgrimage.” These pronouncements were immediately followed by lightning and thunder, after which the figure faded away.

Such an experience would startle and discomfit almost anyone, but it especially shakes Marie, and for a very good reason — she’s an atheist who has nothing but hatred and contempt for religion and mistrust and suspicion for religious people.

Marie’s mother was a barely-practicing Catholic and her father wasn’t religious at all. When her mother died, Marie’s father put her into a Catholic boarding school in Montreal simply to have the girl out of his hair. She hated it there and never forgave her father for ignoring her pleas and abandoning her in a place that tried to indoctrinate her in an unwanted faith. (A convent of the same order as the despised school is in Carmel, near the spot where Marie saw the apparition.)

In the year between her experience in California and the disaster in France, Marie has gone about her life as if the vision never happened; not only did she not tell any priests about it, she has never told anyone else, either. She treats this possible encounter with the divine as if it were a shameful, dirty secret.

Alex’s accident and his strange condition coming exactly one year later — can it just be a coincidence? Marie thinks not; she very much fears that she is being punished for her disobedience, and that her husband is a kind of hostage, that through him she is being compelled to obey the apparition’s directions. She finally speaks to a sympathetic member of the Catholic clergy, Monsignor Cassidy, a cautious, commonsense religious bureaucrat who is nevertheless not insensitive to higher things. Marie’s main concern is not to be publicly implicated or involved in any way in this situation, whatever the church decides to do about it.

As Monsignor Cassidy tries to decide how to handle this situation (he would much rather be swimming or on the links) and Alex continues to lurch between extremes, Marie frantically tries to escape something that she can only think of as a trap; seeing herself as a victim of unseen forces, she suspects every word spoken, every action taken by anyone she meets as a move in a sinister chess game, the object of which is to steal her life from her. With a barely suppressed hysteria, she comes to see herself and everyone else in this drama as little more than powerless marionettes.

Her extraordinary dilemma is finally resolved when the apparition appears again, this time to a nun from the nearby convent. (Marie is present when this happens, but rather than see the vision again she closes her eyes, places her hands over her ears, and flings herself face down on the ground.) As the charge has now been “passed on” to someone else (due to Marie’s adamant refusal?), Monsignor Cassidy assures her that he will completely leave her out of the report that he will make to his superiors. She is free to resume her old life on her own terms.

People are sometimes spoken of as “clinging desperately” to belief; throughout the book, Marie has clung desperately to unbelief, and in the end, she has successfully outrun the Hound of Heaven. At one point, she declares (repeating Catholic doctrine, no doubt unintentionally), “a person has a right not to believe.” Monsignor Cassidy agrees: “I think God has let you go.”

It did not take long for me to remember why I felt a vague dislike when I thought of Cold Heaven — the reason is Marie; she’s a difficult character to warm up to, to say the least. We’re in her head for virtually the entire book, and for the whole course of the story, she’s driven by nothing but fear, hatred, anger, resentment, and suspicion that frequently crosses over into outright paranoia. Even if you think that these reactions are entirely understandable and justified, it’s still extremely unpleasant to be locked up with such a person for two hundred and fifty pages.

She’s also a frustrating character because the above-mentioned reactions and attitudes make her, quite literally, stupid. When she talks to the good-humored and reasonable Monsignor Cassidy or the friendly nuns from the convent, her preconceptions about them and her absolute refusal to concede that their worldview might have anything at all going for it, cause her to be almost literally unable to see them, unable to hear them, unable to understand the simplest things that they say to her, unable to extend them the smallest degree of trust or sympathy. (At one point, when she sees a minister in the hospital, she immediately bristles. She knows that there are always ministers around such places, “bothering people.” It never occurs to her that some people may actually want a minister, may benefit from their presence. If she were told that, she would likely stare blankly; the words wouldn’t even register.)

As she avoids the apparition’s directions, so she avoids any uncomfortable question or issue. She never once confronts the fundamental incoherence of her position, that of thinking that her husband is being threatened and that she’s being blackmailed by something that she doesn’t even believe exists. (Most of the time, she reflexively thinks that some unnamed “they” are forcing her to do what she doesn’t want to do. But exactly who are “they?” A golf-playing prelate and some dirt-poor nuns couldn’t be pulling the strings in a cosmic conspiracy, could they?)

We’re not much better off than Marie, because we never get a clear enough view of this struggle to be able to render a judgment on it — Marie seems to be just a recalcitrant piece of rope in a game of tug-of-war, the real nature of which we never understand, because we never know who’s holding the ends of the rope.

On a more down-to earth level, Marie never understands that she’s just like her hated father, who also would admit no impediments whatsoever to living his life precisely the way he wanted. Likewise, she avoids thinking about the irony of being desperate to save her husband… so that she can tell him that she’s leaving him because she never loved him. (After all, isn’t Alex as much a threat to the life Marie wants to live as any apparition?)

Still, despite its frequently infuriating protagonist, simply taken as an intricate, offbeat thriller, Cold Heaven is often a gripping read. If it ultimately feels somewhat unsatisfactory, that may be because of all the issues that are never addressed, the greatest of which is this — Marie “wins”, in that she successfully rejects the call that was placed on her (which, from everything that we can see, was a genuine one, not a dream, not a hallucination)… but in this context, what does winning mean? Has she really won a hard-fought victory, or has she actually suffered a defeat — one that may have eternal consequences?

That’s the question of questions, but a definitive answer to it can’t be given within the bounds of the story that Brian Moore has given us; perhaps one of the things that he was saying in Cold Heaven is that it’s a question that can’t be answered within the bounds of the “story” that we’re all in, this little life that begins in darkness and ends with a blank wall that it’s impossible to see over.

More now than after my first reading, though, I believe that Brian Moore was canny enough a writer to know what questions his book was posing but not answering, and also to know just what kind of impression Marie is likely to make on readers. I do wonder, though, if it might it not have been better to have given her some corner of herself, however small, that was beguiled — “tempted”, even — by the apparition’s call; it certainly would have made her a less strident, more interesting, more nuanced and sympathetic character. Moore almost certainly considered such a strategy, but we must assume that the Cold Heaven that would have resulted from that change is not the Cold Heaven he wanted to write.

In the end, it might be best to regard this odd, ambitious, unsatisfactory yet haunting novel as a sort of metaphysical nightmare. Some of my favorite books fall into this category — The Man Who Was Thursday by G.K. Chesterton, The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag by Robert A. Heinlein, The Third Policeman by Flann O’Brien, The Land of Laughs by Jonathan Carroll, The Arabian Nightmare by Robert Irwin, Typewriter in the Sky and Fear by L. Ron Hubbard, The Mysterious Stranger by Mark Twain, UBIK by Philip K. Dick, and Conjure Wife by Fritz Leiber are some outstanding examples.

These are books in which the face of reality is veiled, and more than that, in which there is a strong implication that we can never pierce that veil, not because of any inherent limitations in our perception but because the appearance of things has been consciously contrived to deceive us. Contrived by whom? Ah, now that’s a question…

In a metaphysical nightmare, not only is there a sense that reality is inexplicable and sinister (that it’s somehow fundamentally wrong), but the characters must also have an overpowering feeling that they are trapped in that warped reality with no possibility of escape; that’s the nightmare aspect of the story. (The nightmares are literal in several of the books I mentioned, Fear and The Arabian Nightmare, especially, and even in Cold Heaven, where Marie begins having terrifying dreams after she first sees the apparition.)

Metaphysical nightmares are the very opposite of comforting, and reading one can give you a chill that can’t be dispelled by turning up the thermostat; certainly they’re not stories that you read for reassurance. Is the world really like that, though — are we actually living in a metaphysical nightmare? I don’t think so, but I know some people do. (I have to admit that there are days when it’s difficult to disagree with them.) I do know this, though — in a world like that, options are reduced to just a few: faith, despair, madness, or, as in the case of the triumphantly intransigent Marie Davenport, just lower your head, charge forward in your chosen direction, and whatever you do, avoid asking certain questions.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was To Save Your Sanity, Take Steven Leacock’s Nonsense Novels and Call Me in the Morning (or, Why Are Canadians Funny?)

Thank you for the frank discussion of this book, especially given how its subject matter, progression, and character have extra tones and overtones from a Christian perspective. I could have wished for such an in-depth treatment of the first Dekker book I ever picked up, which left similar senses of unresolved questions about a larger existential multi-plane.

I tend to divide books and movies into two apparent perspectives on the universe. “Light Universe” works present the universe as headed toward a good/happy/truthful/correct/positive conclusion, and all troubles presented are those which must be fought for a time but will not ultimately prevail. “Dark Universe” works present the universe as tending toward an evil/sad/puzzling/closed/negative state, and all struggles in the work are for moments of peace or happiness, because a fight is the only way the characters are going to get anything to their benefits. It’s a simplistic division, granted, but difficult not to utilize when the vast majority of works fit so neatly into each category. From my understanding of your article here, “Cold Heaven” fits firmly into the “dark universe” category; would that be a correct understanding?

I would say that that’s so, if for no other reason than the fact that we experience (almost) everything from Marie’s perspective, and that’s definitely how she experiences what’s going on. (The couple of scenes where we get away from her – mostly involving Monsignor Cassidy – feel like a vacation.) I think the nature of what I’ve called metaphysical nightmares (my daughter said I should have called them gnostic nightmares) is fundamentally dark, even if they seem to resolve “happily” (as in The Man Who Was Thursday).

I didn’t mention that the book was filmed in (I think) the late 80’s. I would guess that it’s terrible (It’s IMDB rating is very low) – I can’t imagine how the book could be filmed and retain any of its quality.

That it was filmed is very interesting. I wouldn’t have expected that sort of storyline to be green-lit.

Your daughter has an interesting perspective about “gnostic nightmares” rather than “metaphysical nightmares.” That terminology makes a lot of sense, in nuance. Has she read this book as well?

Not yet!

As for the movie, a little checking shows that it starred Theresa Russell and Mark Harmon (?!) and was directed by Nicholas Roeg, who was sometimes good with weird stories (The Man Who Fell to Earth). Still, I wouldn’t think this would put the butts in the seats…

K. Jesperson’s comment reminds me of the Yea-Sayer, Nay-Sayer topic discussed here:

https://www.sffchronicles.com/threads/567234/

It derives from an issue of Esquire in which Isaac Bashevis Singer (yes) and Eugene Ionesco (No) were asked — well, visit the link and see the discussion.

Thanks Mr. Parker for a thoughtful review and for bringing Black Robe to mind, another book I read many years ago & might reread soon. (I’ve been compiling a list of read-long-ago-might-reread books & Black Robe will be added. Other such books are C. J. Koch’s The Year of Living Dangerously, L. P. Hartley’s The Shrimp and the Anemone, Bruce Chatwin’s On the Black Hill, Dominic Cooper’s Men at Axlir, G. B. Edwards’s The Book of Ebenezer Le Page, A. S. Byatt’s Possession, John Meade Falkner’s The Nebuly Coat, Iris Murdoch’s A Word Child, etc.

Iris Murdoch is someone I need to be better acquainted with, as she deals with many of the issues that I find most interesting. The only problem is that I deeply disliked the one novel of hers that I’ve read (The Unicorn). I’m determined to have another go at her sometime, though.

Thank you for sharing the link to that discussion, Mr. Nelson. Getting to read Isaac Bashevis Singer’s perspective in response to the original question was rather edifying. The discussion of trying to sort authors into the two categories also brought up some valuable points, but I think I most agree with the undercurrent commentary that the authors themselves don’t necessarily fit into the categories as well as particular storylines did.