To Save Your Sanity, Take Stephen Leacock’s Nonsense Novels and Call Me in the Morning (or, Why Are Canadians Funny?)

You need a good laugh right now. How do I know this? I know this because I need a good laugh right now. Everyone I know needs a good laugh right now, so it stands to reason that you need one too, doesn’t it?

So… where to go for that much-needed laugh? Well, there are standup specials on Netflix and the other streamers, you’ve got SNL, there are the many late-night topical jokemeisters — all the usual suspects. Now if that stuff really makes you feel better, more power to you; there’s so much of it available these days, you’re in the enviable position of being a kid locked in a candy factory. For me, though, none of those folks can talk for two minutes without referring to you-know-who who lives you-know-where and is up to you-know-what, and I’m sorry, but all that usually ends up making me feel worse.

To maintain minimal sanity, sometimes what I need most is something that will take me to a place that Thomas Hardy (who briefly hosted the Tonight Show after Conan O’Brien was fired) called “far from the madding crowd.” I don’t want something that’s out to earn my approval because it’s correct; I want something that’s out to make me laugh because it’s funny.

Fortunately, several years ago, I found a fabulous device that accomplishes just that. It’s called… are you ready for this? It’s called a book. And that’s not the half of it. It was written by a fellow named Stephen Leacock, and this guy was… I can’t believe I’m saying this… he was… a Canadian.

How can a Canadian be funny? The answer to that is above my pay grade (could it have anything to do with the fact that for the past two hundred and fifty years, Canadians have had a south-facing front row seat at the world’s most outrageous farce… nah, that can’t be it), but I do know that Canadians are funny, and I’ve known it ever since the mid 70’s when I fell head over heels in love with SCTV, which I believe to be the greatest sketch comedy show of all time, despite the fact that it was mostly a product of Canada. I stopped watching SNL over forty years ago, but I still regularly pop in an SCTV DVD; I just watched one last night, as a matter of fact. In any case, even if Bobby Bitman and Lola Heatherton and Johnny LaRue and Bill Needle and Gerry Todd had never existed, you could still win your Canadian Comic Case by offering Stephen Leacock as exhibit A, and if you won’t take my word for it, the man was Groucho Marx’s favorite comic writer — of any nationality. Think about that — he made Groucho Marx laugh.

That’s funny – he looks funny, but he doesn’t look Canadian

That’s funny – he looks funny, but he doesn’t look Canadian

And yes, he was really a Canadian; though born in England in 1869, Stephen Leacock lived in Canada from the age of six. He was a resident of Montreal and taught economics at several Canadian universities.

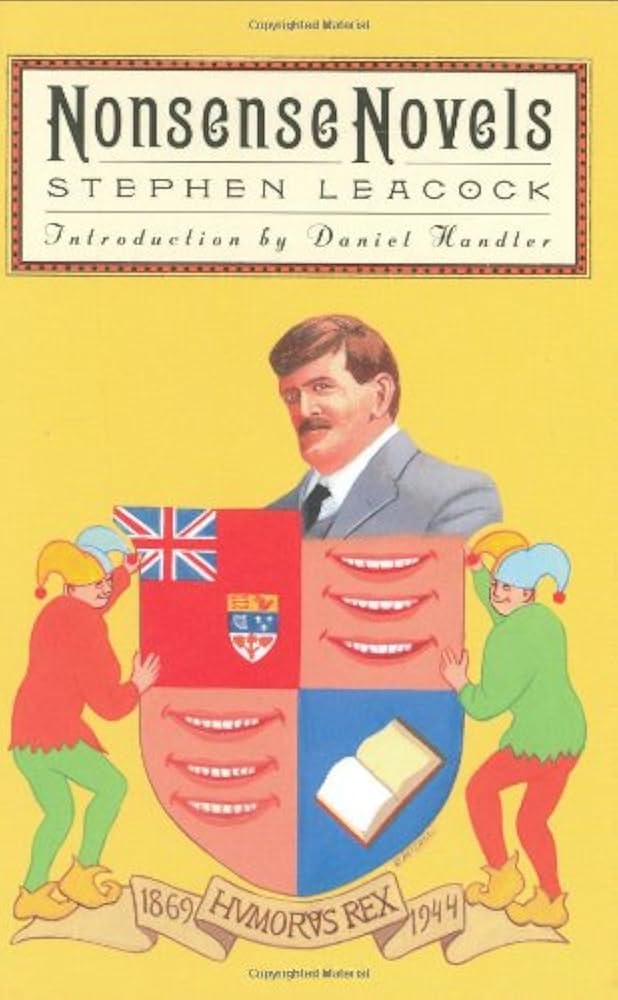

But what you want to know right now is the name of his book, right? The one I’m talking about (he wrote many more) is called Nonsense Novels, and it was first published in 1911. It’s currently available in a few different paperback editions, though the one I have, a nice hardcover from New York Review Books, is unfortunately out of print. I say unfortunately because hardcovers hold up better than paperbacks, and in the time that I’ve had my copy, it’s gotten a lot of hard use. I imagine the same will be true of whatever copy you get your hands on.

Nonsense Novels consists of ten short chapters (each one anywhere from ten to fifteen pages; my NYRB edition is only 159 pages long), and each chapter is a self-contained parody of a nineteenth or early twentieth century popular fiction genre, most of which have been deposited on the ash-heap of publishing, though a few are still alive and kicking. That doesn’t matter, though — the customary devices, the stock characters and situations, the tropes and cliches of each genre have long since been engraved on our cultural memory (through movies, if nothing else) and you’ll have no problem getting the jokes.

So, what we have here are spot-on send-ups of:

The Sherlock Holmesian tale of deduction and ratiocination (Maddened by Mystery or, The Defective Detective), in which the Great Sleuth masterfully assembles all of the clues and comes to the conclusion that the missing “Prince” he’s searching for is not, as he first thought, one of the crowned heads of Europe whose absence will precipitate an international crisis, but is in fact a dachshund whose presence is required at the dog show. He doesn’t locate the animal, but being a master of disguise, a solution easily presents itself to his keen mind: “Rise, dear lady,” he continued. “Fear nothing. I WILL IMPERSONATE THE DOG!!!”

The ghost story (“Q.” A Psychic Pstory of the Psupernatural). “At the moment when Annerly spoke of the supernatural, I had been thinking of something entirely different. The fact that he should speak of it at the very instant when I was thinking of something else, struck me as at least a very singular coincidence.”

A Walter Scott-style hearty historical (Guido the Gimlet of Ghent or, A Romance of Chivalry). “First Guido, raising his mace high in the air with both hands, brought it down with terrible force on Tancred’s mailed head. Then Guido stood still, and Tancred raising his mace in the air brought it down upon Guido’s head. Then Tancred stood still and turned his back. And Guido, swinging his mace sideways, gave him a terrible blow from behind, midway, right centre. Tancred returned the blow. Then Tancred knelt down on his hands and knees and Guido brought the mace down on his back. It was a sheer contest of skill and agility.”

A heart-wrenching story about the trials and travails of a spunky lower-class heroine (Gertrude the Governess or, Simple Seventeen), which begins, “Synopsis of Previous Chapters: There are no Previous Chapters.” The modest charm of the orphaned Gertrude makes her everyone’s favorite: “Even the servants loved her. The head gardener would bring a bouquet of beautiful roses to her room before she was up, the second gardener a bunch of early cauliflowers, the third a spray of asparagus, and even the tenth and eleventh a sprig of mangel-wurzel or an armful of hay. Her room was full of gardeners all the time, while at evening the aged butler, touched at the friendless girl’s loneliness, would tap softly at her door to bring her a rye whiskey and seltzer or a box of Pittsburgh Stogies.”

An inspiring Horatio Alger up-from-nothing success story (A Hero in Homespun or, The Life Struggle of Hezekiah Hayloft). “Such is the great cruel city, and imagine looking for work in it. You and I who spend our time in trying to avoid work can hardly realize what it must mean. Think how it must feel to be alone in New York, without a friend or a relation at hand, with no one to know or care what you do. It must be great!”

A Dostoyevskian drama of living-in-Russia-induced existential madness (Sorrows of a Super Soul or, The Memoirs of Marie Mushenough, Translated, by Machinery, out of the Original Russian). “How they cramp and confine me here — Ivan Ivanovitch my father, and my mother (I forget her name for the minute), and all the rest. I cannot breathe. They will not let me. Every time I try to commit suicide they hinder me. Last night I tried again. I placed a phial of sulphuric acid on the table beside my bed. In the morning it was still there. It had not killed me. They have forbidden me to drown myself. Why! I do not know why? In vain I ask the air and the trees why I should not drown myself? They do not see any reason why. And yet I long to be free, free as the young birds, as the very youngest of them. I watch the leaves blowing in the wind and I want to be a leaf. Yet here they want to make me eat. Yesterday I ate a banana. Ugh!”

A Robert Louis Stevensonish saga of Scotland (Hannah of the Highlands or, The Laird of Loch Aucherlocherty), which chronicles the tragic feud between the McShamuses and the McWhinuses: “It had been six generations agone at a Highland banquet, in the days when the unrestrained temper of the time gave way to wild orgies, during which theological discussions raged with unrestrained fury. Shamus McShamus, an embittered Calvinist, half crazed perhaps with liquor, had maintained that damnation could be achieved only by faith. Whimper McWhinus had held that damnation could be achieved also by good works. Inflamed with drink, McShamus had struck McWhunus across the temple with an oatcake and killed him.”

A Jack London-like sea story (Soaked in Seaweed or, Upset in the Ocean: An Old-Fashioned Sea Story). “By noon of the next day the water had risen to fifteen-sixteenths of an inch, and on the next night the sounding showed thirty-one thirty-seconds of an inch of water in the hold. The situation was desperate. At this rate of increase, few, if any, could tell where it would rise to in a few days.”

A heartstring-tugging Christmas story (Caroline’s Christmas or, The Inexplicable Infant) — the subtitle alone always makes me laugh out loud. “What was that at the door? The sound of a soft and timid rapping, and through the glass of the door-pane a face, a woman’s face looking into the fire-lit room with pleading eyes. What was it she bore in her arms, the little bundle that she held tight to her breast to shield it from the falling snow? Can you guess, dear reader? Try three guesses and see. Right you are. That’s what it was.”

And finally, an H.G. Wells style scientific romance (The Man in Asbestos: An Allegory of the Future): “It seemed unfair that other writers should be able at will to drop into a sleep of four or five hundred years, and to plunge head-first into a distant future and be a witness of its marvels. I wanted to do that too.” The narrator induces his centuries-long sleep by a novel method: “I bought all the comic papers that I could find, even the illustrated ones. I carried them up to my room in my hotel; with them I brought up a pork pie and dozens of doughnuts. I ate the pie and the donuts, then sat back in bed and read the comic papers one after the other. Finally, as I felt the awful lethargy stealing upon me, I reached out my hand for the London Weekly Times, and held up the editorial page before my eye.” That does it; when he wakes up it’s 3000 A.D.

These stories are all unfailingly funny, some riotously so. Leacock hits the genre bull’s-eyes every time; the absurdities of each kind of tale are instantly identified and gleefully exploited, but there’s nothing mean-spirited about these literary burlesques. To write such unerring parodies Leacock had to be well-read in the target genres, and you can see his knowledge, and even more, his affection in every chapter. The book is like a bag holding ten gleaming jewels, but not plastic fakes like the ones kids used to be able to buy at Disneyland for about ten dollars more than you had been planning to spend; every one of Leacock’s treasures is the real thing, a genuine gem sparkling with purest comedy.

Every day we’re faced with a barrage of bad news, and that makes a book as delightful as Nonsense Novels a priceless treasure indeed. Give it a try and I guarantee you’ll feel better; you’ll laugh out loud, not once, but many times, and maybe — just maybe — you’ll even save your sanity.

And by the way — if you know why Canadians are funny, send the answer and five dollars (American) to me care of Black Gate. Cash only — no checks or money orders, please.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was You Are Cordially Invited to a Dinner Party in Hell: The Exterminating Angel

No, he’s not Canadian. Just like we don’t call P.G. Wodehouse American, Leacock isn’t Canadian. They’re just Englishmen who have come to their senses.

Spoken like a true Frenchman!

I’m a longtime Leacock fan, a bit surprised but glad to see him celebrated here. I started out reading early-twentieth-century humorists like Robert Benchley, James Thurber, Ring Lardner, etc. When I found out that the great Benchley and, as you said, Groucho revered Leacock, I had to check him out for myself, and I started with “Nonsense Novels.” He really is the source from which all those others sprang. He wrote in different styles and tones, both humorous and not, but if you love “Nonsense Novels” — and if you can find a copy — try “Over the Footlights” — it’s a collection of parodies of popular genres of plays, and it’s just as funny.

I agree about everyone you mentioned, and would add S.J. Perelman. And of course, how much do so many of them owe to Mark Twain?