You Are Cordially Invited to a Dinner Party in Hell: The Exterminating Angel

Social interaction is a minefield, isn’t it? Whether it’s gathering with the family for the holidays, relating to people at the workplace, or making small talk with the checker at the supermarket, any encounter with other people, no matter how casual or seemingly benign, is fraught with uncertainty and even, sometimes, menace. That may be why such interactions have so often been depicted as a form of combat. (It may also be why the trend towards “contactless” social transactions that reached warp speed with the advent of COVID isn’t going anywhere, but just continues to gain ground even as the Coronavirus era recedes.)

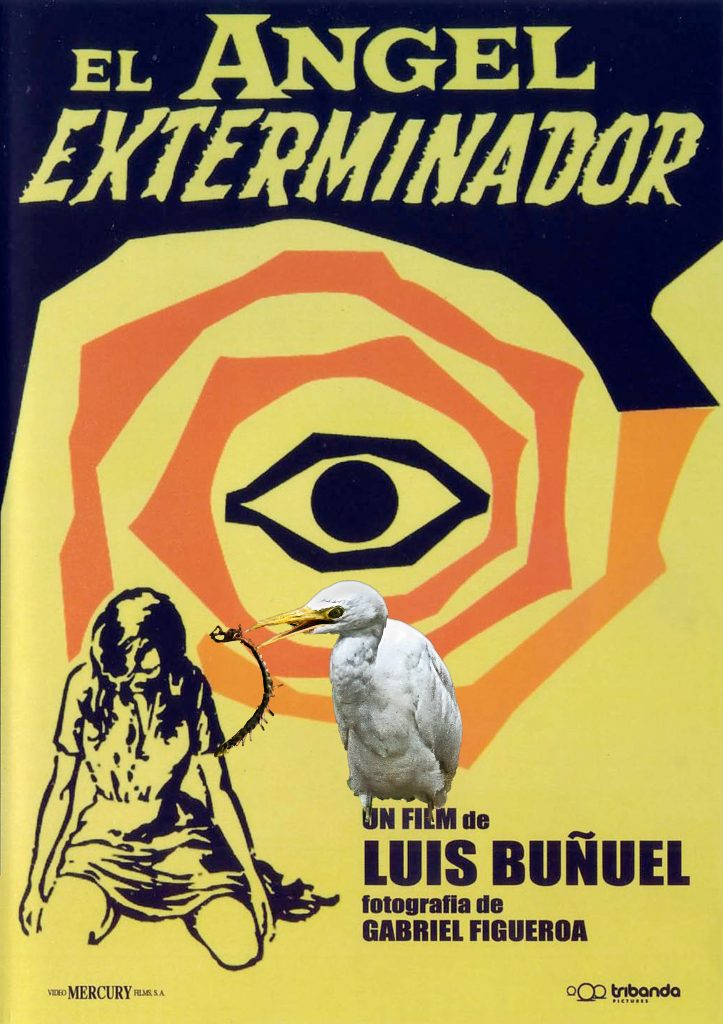

Of all the opportunities for social victory and defeat, triumph and humiliation, the party may be the most hazardous, but no party has ever been such an ordeal as the one endured by the hapless dinner guests in Luis Buñuel’s merciless 1962 nightmare, The Exterminating Angel (in its original Spanish, El ángel exterminador).

Filmed in Mexico and set in a “wealthy district” in an unnamed country (Roger Ebert declares that it’s Spain and that the movie is an attack on the regime of Francisco Franco, but I know of no statement by Buñuel that places the film so specifically or that defines its meaning so narrowly), The Exterminating Angel is the blackest of black comedies; I have no doubt that it would have made the chap who invented the rack and thumbscrews giggle uncontrollably.

Buñuel was one of the original cinematic surrealists, beginning his career in the mid 1920’s and earning his first fame — or notoriety — with two films made in collaboration with Salvador Dalí: that bane of unsuspecting college film students, Un Chien Andalou (1929), with its sudden, shock shot of an eye being sliced open by a razor blade (it was actually a cow’s eye) and 1930’s L’Age d’Or, which provoked scandal and rioting with its unbridled attacks on the Catholic Church.

Buñuel spent the next three decades bouncing between his native Spain, the United States, Mexico, and France, all the while producing work that was unconventional, to say the least. This period culminated with The Exterminating Angel, a film which inaugurated his final and greatest phase, a period which saw him produce his subversive masterpieces Belle de Jour, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, The Phantom of Liberty, and That Obscure Object of Desire.

The Exterminating Angel opens on a beautiful and tranquil night on the Calle de la Providencia, an elegant, upper-class street, as Edmundo Nóbile (Enrique Rambal) and his wife Lucia (Lucy Gallardo) return from an evening at the opera, bringing with them seventeen guests, artists and professional people whom they have invited to join them for a post-performance dinner party. As the gay and sparkling group walks in the luxurious mansion’s front door, the Nóbile’s large domestic staff is rushing out the back; spurred by some obscure impulse that they scarcely understand, cooks, maids, and servers all flee into the night with no intention of ever returning.

Soon the only ones left are several sheep and a bear that the hostess is planning to use for some strange and never-to-be-enacted entertainment, and the Nóbile’s butler, Julio (Claudio Brook), whose total identification with his employers apparently inoculates him against the “running sickness” that is affecting the other servants.

The festivities begin in the time-honored way — the guests sit around the huge table, and oozing well-mannered malice, lean toward their neighbors and cheerfully gossip about the other people at the party, the sexual proclivities and perversions of their “friends” being an especially popular topic. (Other people’s medical conditions are also freely discussed, and an army colonel casually confides to the woman next to him that he doesn’t give a damn about the Fatherland he ostensibly serves.)

After Julio has served the meal, the group repairs to the spacious drawing room, which is only separated from the dining room by an open archway (which looks suspiciously like a theater proscenium), where one of the guests entertains everyone by playing a classical piano piece. More socializing ensues, masks of politesse and good breeding barely concealing the contempt and jealousy that lie beneath. (More than the usual spite and backbiting are hiding behind the polished social surface, however; during the piano recital, a woman opens her purse and has to dig beneath its other contents to reach her handkerchief. What has this elegant society lady brought with her? Lipstick and a compact? No, the feathers and feet of a chicken, the elements of a Cabbalistic ritual.) Finally, as the hour grows late, the partygoers begin to gather coats and purses, in preparation for their leave-taking. Only…

No one leaves. A few people hesitantly walk up to the archway leading to the dining room, which they must pass through in order to reach the cavernous entry hall and the front door, but they pause at the threshold, seemingly unable to take a step further. They stand bemused, expressions of confusion and even fear flickering across their faces, like skydivers at the door of an airplane who suddenly realize that they’re not wearing parachutes (or people standing at the brink of “The undiscovered country from whose bourn / No traveler returns”, perhaps?) They mutter a few weak justifications for staying just a little longer, and retreat back into the drawing room.

It soon becomes obvious that no one is going to leave, as people settle down for the night on couches (the lucky ones), in chairs, or on the floor. At first, the Nóbiles are outraged at this shocking breach of etiquette, but when they realize that they too are powerless to walk out of the drawing room, they find their own places to bed down for the night.

In the morning, Julio wheels in a tray with some breakfast… and finds that he too cannot leave the drawing room, and the new day has brought no change for anyone else, either — no one can leave. The group fumblingly tries to figure out what is happening; almost as frustrating as their inability to leave the room is their inability to understand why they cannot leave the room. Dr. Carlos Conde (Augusto Benedicio), the party’s leading rationalist, counsels that only “dispassionate analysis” can solve the problem, but no one seems much interested in that approach, not that there’s any indication that it would work if they tried it. In the meantime, people are making what arrangements they can — a closet in which large ornamental vases are stored becomes the de facto bathroom, and a pair of young lovers finds another closet where they can be alone; Buñuel allows you to imagine for yourself exactly what they’re up to in there.

As the days pass, territory is staked out, accusations are made and recriminations are hurled, and hunger grows. The lower-class Julio takes to eating paper as he did when a schoolboy and recommends it to the others; it’s better than nothing. An ornamental axe is used to chop through the wall to get to a water pipe; anarchy briefly reigns when water spurts from the pipe, but order is quickly restored — ladies first.

As the prisoners wonder why no one has come to rescue them, we are able to see outside the mansion, where police and crowds of onlookers have gathered, powerless; the same strange force that prevents exit also prevents entrance.

Inside, some react with hysteria, some with lethargy; some fight to maintain hope, some give way to despair. Some people cling to rationality while others call on occult powers, seek help through Masonic rituals, or promise a special mass for their deliverance. All the while, death is a force to be reckoned with inside the house just as it on the outside; lacking his medication, one of the older guests who was in poor health dies after the first night. (Just before the end, he mutters, “I’m happy I won’t see the extermination.”) They put him in the lovers’ closet, which is only fitting, as the pair — who were to be married later in the week — eventually commit suicide together in their trysting place.

An overpowering stench from the improvised lavatory (and morgue) and sweaty, unwashed bodies soon makes the air in the crowded room fetid and foul, and though they can toss their trash into the dining room (despite not being able to enter it), after a few days the drawing room is a filthy, cluttered shambles. Under these conditions, the thin veneer of civilization flakes off as people grate against each other physically and emotionally. Insults and fists fly, and the last tattered remnants of civility begin to disintegrate.

When the erstwhile members of the upper crust are approaching the last extremity, starvation is fended off when the animals escape from the kitchen. While the bear roams the upper floors, emitting eerie moans and cries, the sheep providentially trot into the drawing room; whatever sardonic divinity presides over this hell, he is at least willing to provide manna for his erring children. A fire is made from smashed furniture and soon roast mutton is being devoured by people indistinguishable from their primitive ancestors, who also squatted around open fires, eagerly tearing meat off of bones with their teeth.

Full stomachs only sharpen the edge of the guests’ desire to escape their prison, however, and a group of women (among them the devotee of Kabbalah) begin to push the idea that only a sacrifice — a human one — will free them. Who should the victim be? Who better than their host, the man who got them all into this mess with his impertinent dinner party invitation, Edmundo Nóbile? (Who, it must be said, has lived up to his name by comporting himself with more dignity and self-control than almost anyone else.) Some oppose this move, the ever-reasonable doctor most prominent among them (for his pains, someone shouts that they should get rid of him too) and the two sides, those for human sacrifice and those against it, wind up wrestling in the middle of the ruined room.

Just as the pro-sacrifice faction seems to be getting the upper hand and someone is reaching for the same knife that was used on the sheep, Nóbile tells them all that it won’t be necessary — taking a pistol from a drawer, he says that he can easily solve their problem for them. But before he can use the gun on himself, one of the women, Leticia (the wonderful Silvia Pinal, a Buñuel regular) tells everyone to stop where they are — she has realized that are all in the exact same places they occupied when the nightmare began, countless ages ago. If everything is repeated — positions, music, words, gestures, might that not free them from this spell? (Buñuel has slyly prepared for this by repeating several shots in the film; for instance, the shot of the guests first entering the house, along with the accompanying dialogue, is shown twice in succession. The only difference is a slightly different camera angle. Buñuel claimed that there are about twenty of these repetitions in the film.)

Everyone (except the dead) exactly repositions themselves as they were that unlucky night. The last few bars of the piano piece are played, followed by the same words that were spoken, and the doors of the sorcerer’s castle (“after all, this is not a sorcerer’s castle” someone rashly declared after the first night) are miraculously unlocked, and the captives are free. They immediately sense that whatever was restraining them has disappeared, and they ecstatically rush out the front door to meet the people waiting outside, who are also now freed to run to meet them. (Even the servants are there, seemingly drawn back by the same force that impelled them to run away.)

The curse has been lifted and the evil dream can fade from memory as all dreams do.

Well, if you think that, you don’t know Luis Buñuel. Of course, this deliverance is illusory; the torture master has withdrawn the knife only to reinsert it, merely repositioning the blade for the final, fatal twist.

The last scene of The Exterminating Angel shows all the dinner guests, again clean and fresh, immaculately groomed and expensively dressed, gathered together in church along with hundreds of other worshippers, attending the special mass that they promised to celebrate if they were saved from their ordeal.

As the service ends and the bells toll, the priests start to walk out of the nave… and stop.

They cannot leave, and neither can anyone else; they all stand paralyzed, new captives and old alike unable to walk through the door in front of them, and not long afterward, as panic mounts inside the church, shouts are heard from the outside, where mounted police are clashing with a large crowd. Rioters or the merely curious? Does it matter? The disorder and chaos that leaked from the human heart into an elegant upper-class drawing room has now overflowed into the wider world, spreading through the streets like a plague.

But have no fear; the degraded human race, corrupt and corrupting, will be looked after. The final shot of this extraordinary film shows a large flock of sheep, placidly trotting through the doors of the church while the city outside echoes with screams and gunfire. FIN.

The Exterminating Angel is one of the greatest films ever made, bursting with resonant, unforgettably suggestive images — a bear climbing the pillar of a chandeliered hall, crying with what sounds like anguish; sheep roaming up the wide stairways and through the deserted rooms of a richly-appointed mansion; ragged people listlessly standing around in the shattered ruins of what was once an elegant drawing room, hopeless as damned souls in hell; Nóbile and Leticia sitting with a sheep between them — as Leticia blindfolds the animal and hands Nóbile a knife, the doomed creature tenderly lays its head on its executioner’s shoulder. (Buñuel later said he wished that he had left the animals out of the film, because then he would have been able to make his people resort to cannibalism. Fun guy, that Luis.) Though there are a few other works it brings to mind (Jean-Paul Sartre’s play No Exit, which came before the film, and J.G. Ballard’s novel High Rise and Jean–Luc Godard’s film Weekend, which came after) The Exterminating Angel is very much its own thing, a bracingly original achievement, a ticking time bomb placed under the padded chairs of the complacent.

What is the meaning of this savage allegory? Does it say that hypocrisy and malice constitute the irreducible baselines of human behavior? That the comfort and luxury that we almost all desire are nothing but degrading prisons? That life is defined by its frustrations? (Later, in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, Buñuel plays a variation on the impediment faced in the earlier film; in Discreet Charm the people of the privileged class can go where they want, but every time they sit down to dinner, something prevents them from eating; they are never allowed to complete a meal.) Does it say that the world is nothing but a desert island where we are all shipwrecked? (In 1954, Buñuel had filmed his own version of Robinson Crusoe.) Is it about the loss of belief that can suddenly undermine the most powerful regime? (Buñuel didn’t live to see the Soviet Union collapse overnight, but if he had, I can’t imagine that he would have been very surprised.) Is it a parody of the Book of Exodus? (When the Destroying Angel passed over Egypt, the Children of Israel couldn’t leave their houses.) Is it a monument to misanthropy, a horror movie in which the monsters are other people?

Hell, maybe if you could have administered a truth serum to the cagey Spaniard, he would have told you that the movie isn’t about the people at all — it’s about the sheep.

All respect to Roger Ebert, but whatever this singular film is, it has to be more than just a declaration that under Francisco Franco, Spain was oppressed by a corrupt and evil government. We know that already, and having grasped that fact, there’s nothing more to add. But The Exterminating Angel is deep enough to convey that specific meaning and many, many more. Like all the greatest works of art, it’s almost limitlessly expansive; it contains more and means more every time you see it. (Watching in 2025, it’s hard not to attach a meaning to it that it couldn’t have had for its director or original audience in 1962; the film works perfectly as an allegory of the anxiety and isolation of the COVID era.)

In watching this eccentric masterpiece, you may find yourself appalled, shocked into bitter laughter, filled with pity and dismay at the irremediably tainted human race and its benighted condition. What you won’t be is bored or dismissive; you’ll have no doubt that you’ve seen something absolutely unique and uncomfortably pertinent to the human dilemma, and you’ll find yourself turning it over and over in your mind long after the final credits have rolled, looking for a way out.

Really, what more could we poor, stupid sheep ask for?

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was The Beating Heart of Science Fiction: Poul Anderson and Tau Zero

Part of me wants to be done with the spectacle you’ve so carefully described by saying something trite, like, “Well, that’s a load of nightmare fuel.” The rest of me already can’t let it go, regarding the movie askance and trying to figure it out. Visions of a world with pity but without grace? Perhaps not, if Bunuel desired to remove even the sheep on second consideration, because then there would be no pity to cast into relief the lack of grace.

Some form of lesson inscrutable to the living, only perceived by the dead or dying, that was not sufficiently learned in the first go-around? Or a supernatural experiment deemed a success in small application, so expanded to a larger population? And if it gradually expanded to the whole world, would the nature of whatever is going on be able to be fulfilled at the point when there are no longer groups of sheep to send in to new groups of the trapped?

Urgh. I don’t think I need to watch the movie. You have sufficiently related it to turn my brain into a pretzel, Mr. Parker. Very well done.

Buñuel was adamant that in contrast to Sartre’s No Exit, his people weren’t dead. The Exterminating Angel is certainly some sort of allegory, but it’s not an allegory of any kind of afterlife.

You should certainly give it a try – believe it or not (and I can see why it would be a “not”), it’s great fun to watch!