The Beating Heart of Science Fiction: Poul Anderson and Tau Zero

Science fiction — what is it, really? What elements place a story firmly in the genre? For any requirement that you can think of, there is probably a great sf story that violates it, and rather than cobble together some dictionary-ready definition, it’s easier to just think of particular books that you would hand to someone unacquainted with the genre with the words, “Here — read this; this is science fiction!”

Everyone would have their own choices for such a list, of course, and those choices would amount to your de facto definition. For me, some of those books would be Rendezvous with Rama by Arthur C. Clarke, The Stars My Destination by Alfred Bester, and Man Plus by Frederik Pohl, but the very first book on my list would be Poul Anderson’s 1970 novel Tau Zero. Why? What does this book have that makes it a quintessential work of science fiction?

Maybe it’s this — it’s a grand voyage, a brave excursion into the great out there, and it also has a grand perspective shift, like a camera pulling back in a movie, a maneuver that radically alters everything that you had previously thought about the story, something that’s not a minor adjustment, but a move that completely explodes the frame. You think the story is this, but it’s really that, you think you’re here, but you’re really there; the here where you thought you were turns out to be the tiniest corner of there, a there that is larger and stranger and more dizzying than you ever could have originally imagined. (In The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Peter Nicholls calls this kind of maneuver a “conceptual breakthrough.”)

Tau Zero begins as a straightforward story of an interstellar voyage, but it ends as far away from that prosaic beginning (prosaic by the standards of science fiction, I mean) as it is possible to imagine. Farther than that, really, and I think that’s the whole point.

Sometime in the 23rd century, the colonization ship Leonora Christine sets out from earth for a planet thirty light-years away. Unlike many stories of this type, the voyage isn’t prompted by the world coming apart at the seams; generally, things are going quite well, which is largely due to the people of the planet submitting to a global government run exclusively by… Scandinavians. Everyone just handed the reigns to the Nordic folk because of their universally acknowledged rationality, efficiency, impartiality, and lack of any pesky Will to Power. I know, I know — send any complaints to that son of Denmark, Poul Anderson. I guess he figured he would inoculate his readers against all the wildness to come by giving them the nuttiest thing first.

If the interstellar colonization mission is a stock situation, Anderson peoples it with characters that are themselves mostly recognizable types. The Leonora Christine’s Captain is Lars Telander, a solid, stolid, stoic father figure who seems ideal at the beginning of the journey, but who fades (if not wilts) into the background under the stresses of the voyage and the extraordinary emergency that the crew eventually has to deal with. More central to the life of the ship and the story Anderson tells are First Officer Ingrid Lindgren, ultra-competent while still being sensitive and sympathetic, and the book’s real protagonist, Ship’s Constable Charles Reymont, willing to be as much of an unlikable, hard-nosed SOB as necessary in order to hold the crew together and complete the mission. Reymont’s and Lindgren’s on-again, off-again romance and their consciously embraced good cop/bad cop roles form the human core of the story.

Anderson devotes significant time to this pair and to the other crew members whom they alternately coax (Lindgren) and steamroll (Reymont) on the way to their goal. In one sense, the book is a tract on the dynamics of leadership in a uniquely stressful situation, and the author had clearly thought a lot about such problems and had some definite ideas about how to deal with them.

It has to be said, however, that Anderson’s depiction of character rarely rises above a fairly rudimentary level; there’s an off-the-rack feel to most of his people. What we have here isn’t Henry James in space, and stylistically, the book wasn’t written to dazzle; if you’re looking for graceful allusiveness, poetic imagery or memorable turns of phrase, you need to look elsewhere; Anderson’s prose generally doesn’t rise above the level of “workmanlike” (which doesn’t mean that it’s bad — it usually has the far from negligible virtues of efficiency and clarity). So, old Poul is no Nabokov in space, either.

So what? Tab A in Slot B prose and slide-rule stiff characters are hard-sf traditions that go back all the way to the vacuum-busting days of Hugo Gernsback (and Anderson’s work isn’t nearly as wooden as the stuff old Hugo published), which just means that you adjust your expectations when you read this kind of sf story. (Oh, what’s a slide rule? Google it, kid.)

In the long run, Anderson’s deficiencies are perfectly acceptable because what you read Tau Zero for is the writer’s wide-screen vision and the extraordinary crisis his people face, and what a vision! What a crisis!

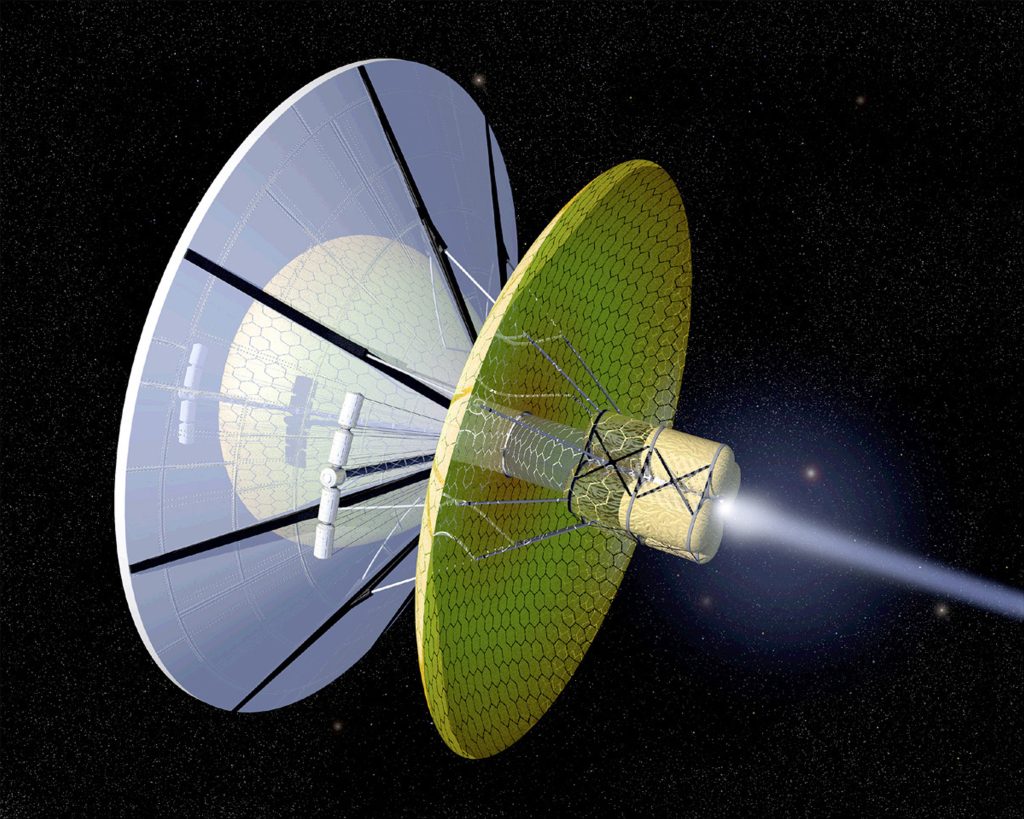

The Leonora Christine powers itself by collecting hydrogen as it travels through interstellar space and using it for fusion. (Technically this makes the ship a Bussard ramjet, though Anderson never uses the term.) As such a ship can approach the speed of light but cannot exceed it, the vessel’s flight plan is to accelerate up to near light speed during the first half of its voyage and then steadily decelerate down from that halfway point until it arrives at the target planet. Because of the relativistic time dilation caused by its extreme speeds, over thirty years will pass on earth while only five years will pass on board the ship.

Initially, things go smoothly as the crew settles into the routines that will occupy them during their long journey, and as expected, people (half of the multinational, fifty-person crew are male and half are female) begin to pair off in preparation for life as colonists on their new world. Everything seems to be going according to plan, until, before reaching the midway deceleration point, the Leonora Christine collides with an unanticipated interstellar dust cloud; because of the ship’s increased mass (due to its speed) this is potentially a very serious event, more like slamming into a brick wall than strolling through a fog bank.

At first, the ship seems to come through this emergency surprisingly well, but the truth soon becomes apparent. The collision has caused irreparable damage to one vital system — the one used for deceleration. The Leonora Christine is unable to slow down.

Why is the damage irreparable? To make repairs, it would be necessary to exit the ship, but the engines generate radiation that would be instantly fatal to anyone outside the hull, and the engines cannot be shut down because they generate an electromagnetic field which is the only thing protecting the crew from the hard radiation of galactic space. (The darn thing must not have been designed by Scandinavians.)

Reymont, Lindgren and the rest are thus faced with the prospect of an endless, pointless voyage that can only conclude with their own deaths from accident, old age or despair, sealed inside something that began as a ship, turned into a prison, and can only end as a coffin. Such an appalling situation would be bad enough, but the Leonora Christine’s crew soon comes to an even grimmer realization.

Unable to decelerate, the time dilation that was to have initially separated them from their home by a mere thirty years is only growing more extreme. The stunned crew members quickly realize that it is not decades that are passing outside the ship, not centuries, not millennia, even. “Soon”, millions, and then billions of years have passed. The would-be colonists whose aim was to open a new world for people from earth to live on must now accept that earth’s sun has long since burned to a cinder, their planet has vanished, their species has become extinct. The fifty exiles on the Leonora Christine are the last human beings alive in the universe, and unless they can find a solution to their dilemma, they are the last human beings that there will ever be.

How will they respond? Panic? Madness? Suicide? Reymont and Lindgren (especially Reymont) are resolved to hold the crew together, determined that they will all continue to do their jobs in the hope (hope being one of the defining characteristics of the late, great human race) that they will eventually find some way to slow down and locate some world, somewhere, where they can make a new start and keep their species alive.

Despite being more radically alone than any human beings have ever been (at one point, someone quotes Father Mapple from Moby Dick — “for what is man that he should live out the life-time of his God?”), for the most part, the Leonora Christine’s people respond well; the extreme strain sometimes produces extreme effects, but no one commits suicide. (I suspect that Anderson knew that in such a situation, if just one person took that way out, it would likely be the effective end of everyone.)

Soon they have left, not only our own galaxy, but also the supercluster of galaxies that constitute our local “neighborhood”, in the hope of reaching a region in which radiation levels will be low enough to permit them to make their repairs. As these “empty” gulfs are completely uncharted, they are also trusting that chance (or that God whom some of them still believe that they have not outlived) will eventually bring them to a galactic group where they will find a suitable planet.

Unexpected difficulties continue to intervene, however, and by the time they are able to fix the damage and decelerate to begin their search for a new home, there is no longer any potential home to decelerate to; so much time has passed outside the ship that the expansion of the universe caused by the original Big Bang has reversed. The universe is now contracting in a “Big Crunch” in which all matter and energy are forced closer and closer together until the cosmic cycle will restart with another Big Bang.

What is there for the Leonora Christine to do but circle the cosmic seed and attempt to ride out the coming explosion and then try to find a young world to begin again on? That’s just what they are able to do, and the story that began on an old planet in an old galaxy in an old universe ends on a new planet in a new galaxy in a universe that didn’t even exist when the story began, uncounted trillions of years before.

The book closes with Charles Reymont and Ingrid Lindgren, two people who now constitute one twenty-fifth of the entire human race, standing on the soil of the home they have travelled such an inconceivable distance in time and space to reach. “Here was not New Earth”, Anderson says. “That would have been too much to expect.” But it is a place where the stubborn, resourceful, endlessly hopeful human race will be able to start anew, a place where it will have a chance to take root and flourish… and perhaps, avoid some of the mistakes that plagued it long ago in a universe that now no longer exists.

Charles Reymont, the man whose determination saved the entire human race, lightly rejects the suggestion of kingship that Ingrid Lindgren jokingly (but also not entirely unseriously) makes, and then “he laughed, and made her laugh with him, and they were merely human.”

Pardon my French (a language once spoken on the long-extinct planet earth), but… holy shit!

Tau Zero was called by James Blish the “ultimate hard science fiction novel.” It’s certainly difficult to think of one that could go beyond it; every time I finish reading it, I want take my brain out, shake it a little, massage it, and run it under a cold faucet before putting it back in my skull. It’s a book that takes your perspective and stretches it, and stretches it, and keeps on stretching it until you walk around bumping into walls because you’re so far from where you started that you have no idea where you are anymore and can’t even begin to imagine where you’re going to end up when you’re finished.

Even in the science fiction genre, there aren’t many books like that. Even a lemon-sucking, hard line anti-Campbellian anti-sentimentalist like Barry Malzberg grew positively misty whenever he talked about the book. Calling the novel “magnificent”, Malzberg rhapsodized that Tau Zero was “the only work published after 1955 that can elicit from me some of the same responses I had towards science fiction in my adolescence — a sense of timelessness, human eternity, and the order of the cosmos as reflected in the individual fate of every person who would try to measure himself against these qualities.”

This wasn’t just Malzberg indulging in nostalgia; Poul Anderson’s book, which marries a modest nuts-and-bolts style with a beyond-audacious premise, really does what Malzberg says it does, and in doing so it goes beyond the merely mind-boggling; it squares the boggle and keeps on squaring it until you’re so dizzy with infinitely expanding possibility that you have to lie flat on the floor for a while. For me, it’s the wildest, most exhilarating trip in all of science fiction.

I’m not going to return to the definitional task that I disavowed when I began this piece, but I do know that one of the things that we most want from a science fiction story is that when we finish it, we won’t end up back where we started. We want it to take us on a voyage, the kind of voyage that no other kind of writing can accomplish or even attempt.

If you want to know what kind of voyage that might be, I can do no better than to turn you over to one of the genre’s greatest voyagers, Poul Anderson, and commend to you his indeed magnificent novel, Tau Zero. When you’ve finished reading it, you might just feel — along with me — that what you’ve been holding in your hands is nothing less than the beating heart of science fiction.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was The Gorey Century

I haven’t read Tau Zero, though I have a copy. That said I believe Anderson is underrated. He was AT LEAST as good as any of the Big Three (Heinlein, Clark, Asimov.)

The mind-melting moment that I recall from Tau Zero is the shuddering of the ship as its collector is swallowing entire galaxies as its own mass zooms off toward infinity. I also love it as a exemplar hard-sf work since it performs the sleight-of-hand magic of hard sf (breaking the laws of cosmology without the reader noticing, since a Big Crunch would include all space-time and thus the ship, too) to give us a journey of a trillion years, all in 190 pages (in my Gollancz SF Collectors edition).

Blish’s praise for Tau Zero is interesting in that his own The Triumph of Time (aka A Clash of Cymbals), the concluding volume of Cities in Flight, features, er … essentially the exact same ending as Tau Zero.

I should add that your review of Tau Zero captures my feelings when I read it 50 years ago. I really should reread it.

I can’t remember when I first read it – maybe thirty years ago – but I reread it at Christmas to prepare for this piece. I was worried about it not holding up. Though the science has dated (I believe the Big Crunch theory isn’t much accepted anymore) the book still passed the shiver test. I think Barry Malzberg would be pleased!

I always thought the definition of science fiction is that “science” must be an underlying element of the story. Take away the science, there’s no story. It’s okay if that science is since disproved or not actually workable by today’s concepts (see faster than light travel). There’s really no science in Star Wars, despite the spaceships and other worlds, it’s actually fantasy. The same could be said of much of Star Trek. On the other hand, to employ a variation of the tired cliche, I know science fiction when I see (read) it.