Across Time: Claude Moreau and His Translator Scott Oden in Conversation

This post packs two punches:

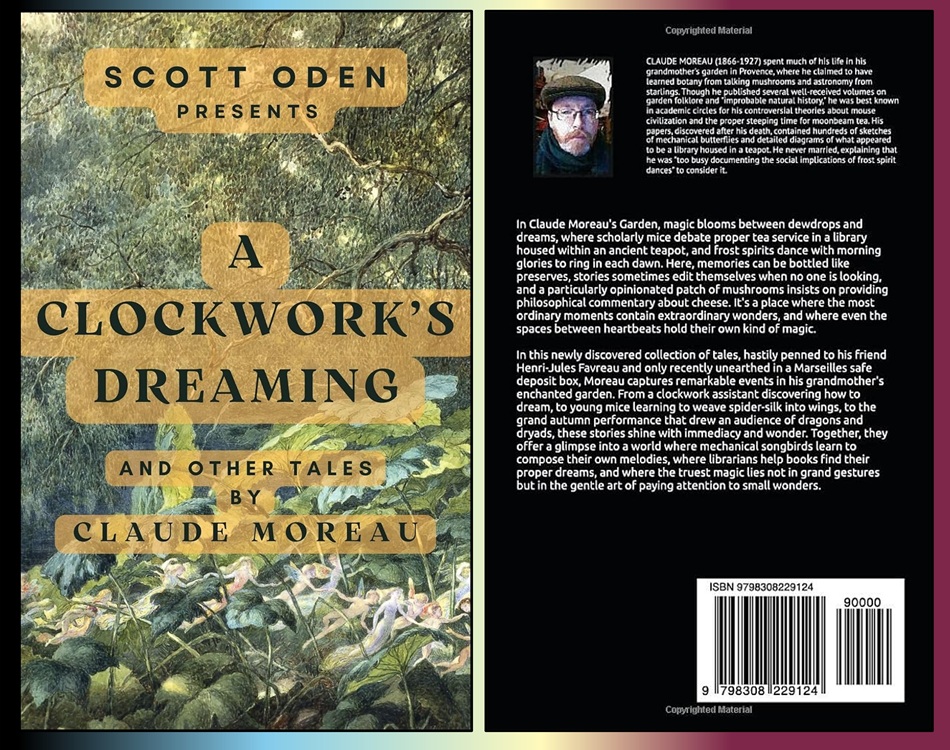

- A showcase of the New Treasure A Clockwork’s Dreaming: And Other Tales by Claude Moreau and Scott Oden (January 2025, 134 pages, Kindle and Paperback).

- An exclusive interview with the deceased author Claude Moreau, the living translator Scott Oden, and special appearances of Laurent Dupont, editor of the literary magazine Les Petites Merveilles. Yes, this article is historic and magical. Read on to learn how this came to be.

A Clockwork’s Dreaming

“In Claude Moreau’s Garden, magic blooms between dewdrops and dreams, where scholarly mice debate proper tea service in a library housed within an ancient teapot, and frost spirits dance with morning glories to ring in each dawn. Here, memories can be bottled like preserves, stories sometimes edit themselves when no one is looking, and a particularly opinionated patch of mushrooms insists on providing philosophical commentary about cheese. It’s a place where the most ordinary moments contain extraordinary wonders, and where even the spaces between heartbeats hold their own kind of magic.

In this newly discovered collection of tales, hastily penned to his friend Henri-Jules Favreau and only recently unearthed in a Marseilles safe deposit box, Moreau captures remarkable events in his grandmother’s enchanted garden. From a clockwork assistant discovering how to dream, to young mice learning to weave spider-silk into wings, to the grand autumn performance that drew an audience of dragons and dryads, these stories shine with immediacy and wonder. Together, they offer a glimpse into a world where mechanical songbirds learn to compose their own melodies, where librarians help books find their proper dreams, and where the truest magic lies not in grand gestures but in the gentle art of paying attention to small wonders.” – Cover Summary

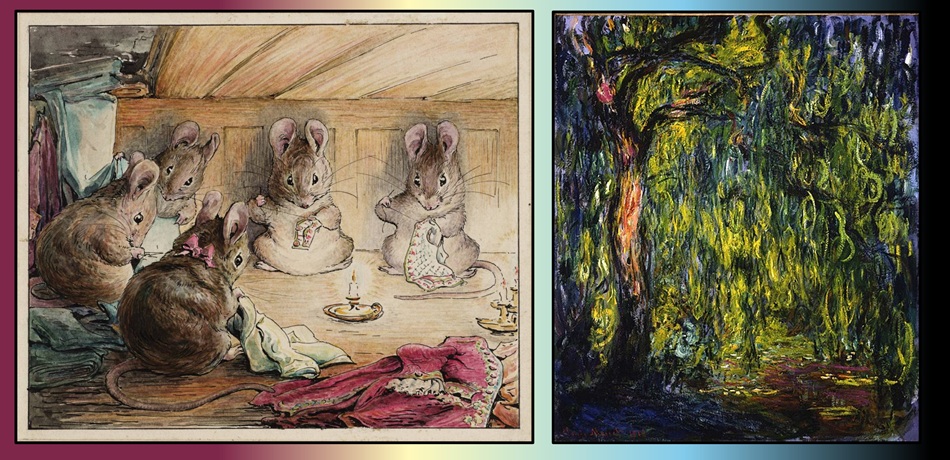

Oden just released A Clockwork’s Dreaming: And Other Tales (January 2025). The content holds remarkably true to his adventure telling and love of historical fiction, but is completely different than his grimdark portfolio. Oden shifted toward inspirational, non-grim fiction with this. There are six stories plus pre and post-commentary. All stories are easily digestible. The introductory premise resonates with the weird fiction vibe having the narrator/translator deciphering letters from deceased scientists/gardeners who experienced the supernatural. Instead of the experience being horrific, these are all uplifting. The initial tales calibrate the reader to a world reminiscent of C.S. Lewis’s Narnia (i.e. talking creatures). Readers should expect anthropomorphized mice and trees, heck, even “stories” become sentient and assume tangible substance. Terms like “astronomical gardening” and situations like “books were talking about feeling colorless” saturate this wonderful collection.

“The Maples’ Grand Performance” story mesmerized me until I cheered for the finale. Next, a homage to Lord Byron’s “Ozymandias” poem showcased a heroic mouse of the same name tackling greed and achieving a legacy; this swelled me with optimism. The titular tale “Clockwork’s Dreaming” at first evoked, at least for my Gen X mind, the owl Bubo from the 1981 Clash of the Titans, since it involves a mechanical bird. Oden’s character is actually a fun protagonist (not a goofy sidekick). After you read the book, you’ll be compelled to dig into Claude Moreau’s Garden website which has many complementary tales.

With A Clockwork’s Dreaming, Oden inspires readers via tall tales featuring heroic mice.

Oden’s prose impacts as much as his grimdark tales, but smacks with beauty and peace!

An Exclusive Interview with Moreau, Oden, and Dupont

In January 2025, while researching in the rarely-accessed archives beneath Black Gate headquarters, I discovered a cache of remarkable documents, fragments of an 1899 interview with Claude Moreau conducted by Laurent Dupont, editor of the literary magazine Les Petites Merveilles. The fragile pages were nestled between volumes of obscure grimoires and games of strategy, and appeared to shift location between visits to the archive. It is unclear if John O’Neill knew he had these documents since they were uncharacteristically absent from his meticulous card catalog.

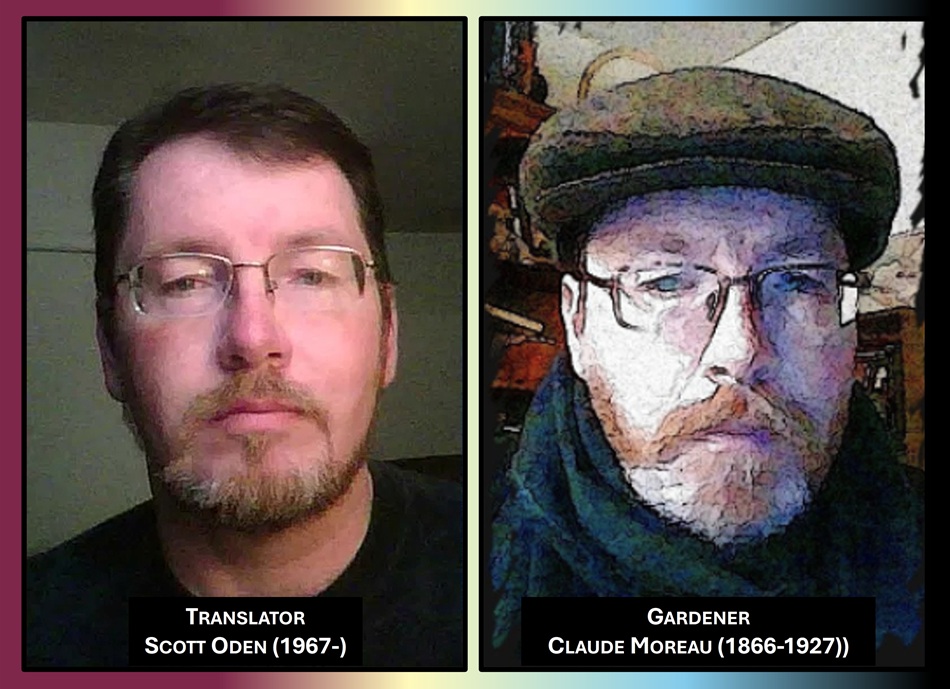

Even more remarkably, these historical fragments seem to resonate with the questions for Scott Oden, translator of Moreau’s recently discovered works and longtime friend/contributor with Black Gate. What follows is an unprecedented conversation across time: Moreau’s words from 1899 alongside his translator’s reflections in 2025. Where the original document was damaged or illegible, we rely solely on Oden’s modern perspective.

The original document is reproduced with permission from the private collection of John O’Neill.

Across Time: Claude Moreau and His Translator Scott Oden in Conversation

On the Nature of Moreau’s Work

BLACK GATE (2025): As per the prologue to A Clockwork’s Dreaming, you “discovered a remarkable collection of letters, pressed flowers, and curious objects that can only be described as fairy wings and dragon scales. The correspondence was from Claude Moreau to his friend Henri-Jules Favreau, written between 1897 and 1898.” Please introduce newcomers to Moreau’s works. What should they expect?

ODEN (2025): Claude Moreau was an Impressionist painter who, after a rather disastrous exhibition in Paris (the notorious ‘Incident of the Purple Cats’), retreated to his grandmother’s cottage in rural Provence. There, while attempting to document the garden’s more conventional aspects, he began noticing… unusual activities. His letters to Henri-Jules Favreau, a professor of Improbable Literature at the University of Aix-en-Provence, chronicle an entire hidden world within his grandmother’s garden — a place where mice maintain libraries in forgotten teapots, where mechanical creations dream of becoming more than their gears, and where memories can be preserved in specially crafted jars.

Readers should expect stories that exist in the space between wonder and reality — tales that don’t shy away from life’s shadows but find beauty and courage in gentleness rather than conflict. These aren’t simply children’s stories, though children often grasp their truth more readily than adults. They’re accounts of a world that operates according to different rules than our own, yet somehow illuminates truths about our reality. Unlike my usual historical fiction or the adventures of Grimnir, the Garden tales offer a different kind of magic — the extraordinary possibilities hiding within ordinary moments.

DUPONT (1899): Monsieur Moreau, your tales of life in your grandmother’s garden have caused quite a stir among our readers. Many write to ask if these stories are meant to be taken as fact or fancy. How would you respond?

MOREAU (1899): My dear Dupont, I find such distinctions increasingly tiresome. Is a sunset less beautiful if one understands the scientific principles behind refracted light? Does knowing the Latin name for a flower diminish its scent? I simply record what I observe in my grandmother’s garden, with as much accuracy as my humble talents allow. Whether readers choose to see these observations as literal or metaphorical matters less than whether they recognize some small truth within them.

DUPONT (1899): Yet you speak of talking mice, singing flowers, and mechanical devices that develop consciousness. Surely you understand why readers might question—

MOREAU (1899): I understand perfectly why people raised on the rigid categorizations of modern thought might struggle. We are taught from an early age to separate the world into neat compartments: reality and fantasy, science and magic, fact and fiction. But the Garden exists in the spaces between such artificial boundaries. The mice don’t “talk” as you and I are doing now—they communicate in ways that require a different kind of listening altogether. As for mechanical consciousness, well… [pauses to sip tea] Have you never observed how certain objects seem to develop personalities over time? How a well-loved book begins to open naturally to its owner’s favorite passages? Or how a clockwork mechanism that has run for decades seems to develop its own subtle rhythms beyond mere mechanical precision?

On Literary Connections

In 1896 Claude Moreau’s contemporary H. G. Wells published The Island of Doctor Moreau; is there a relationship between these scientifically curious Moreaus?

What an intriguing coincidence! Though I’ve found no direct evidence that Claude Moreau and H.G. Wells ever met, there’s a certain synchronicity in their work appearing around the same time. Both dealt with boundaries between the natural and unnatural, though in radically different ways.

Where Dr. Moreau attempted to force nature into unnatural forms through scientific hubris, Claude Moreau documented the quiet magic that emerges when nature is allowed to follow its own extraordinary course. One sought to control and transform; the other simply observed with careful attention and wonder.

I sometimes imagine them encountering each other at some Parisian café — Wells with his scientific skepticism and Claude with his dreamer’s heart — engaging in a spirited debate about the boundaries between reality and fantasy. What a conversation that would have been!

DUPONT (1899): Several critics have suggested your tales are simply allegories — clever ways of discussing human relationships through the filter of imagined garden creatures.

MOREAU (1899): [laughs] Critics will always seek to explain mystery rather than simply experience it. Perhaps there is something allegorical in my accounts. The Garden certainly has much to teach us about human nature. But to reduce these stories to mere invention would be to miss their essential truth. The Garden exists, Monsieur Dupont. Whether one can find it on any conventional map is beside the point.

On The Garden’s Libraries

Moreau’s Gardens appear to be sprawling, like a Botanical Garden complex with many subgardens. The quote below indicates the subgardens are ‘libraries.’ How many flavors of libraries & gardens exist?

“There are libraries that exist beyond the knowledge of most garden visitors — collections not of books but of potential and promise, cataloged with a precision that would impress even Mr. Thistledown himself.” From the Seed Librarians

As chronicled in Moreau’s letters, the Garden contains numerous libraries beyond the main one housed in the teapot. The Library proper primarily holds stories and knowledge in traditional book form (though ‘traditional’ may be stretching it, given that some volumes reportedly change their contents depending on the phase of the moon).

But yes, there are specialized collections throughout the Garden. The Seed Library maintains living knowledge of plant species both common and forgotten, preserving not just physical seeds but the stories and songs that help them grow. The Memory Archives, maintained by Grandmother Elderberry and her apprentices, preserve experiences in specially crafted jars. The Frost Spirits maintain crystalline records of winter patterns dating back centuries, while the underground chambers beneath the Old Stone Wall house historical artifacts too delicate for conventional preservation.

Each ‘library’ serves as a repository for different types of knowledge, operating according to principles uniquely suited to what they preserve. The Seed Librarians, for instance, understand that some knowledge must be planted rather than simply shelved; allowed to grow and change with the seasons rather than remaining static.

DUPONT (1899): Speaking of the Garden, many readers have written asking about its precise location. Is it somewhere they might visit?

MOREAU (1899): [laughs] The Garden exists precisely where it needs to be. Those who seek it with open hearts occasionally find their way there, though rarely by any conventional path. I’ve noticed that children often discover it without difficulty, while adults struggle — particularly those who approach life with rigid certainty about what is and isn’t possible.

But perhaps I can offer this small hint: the Garden is most accessible during those in-between moments when the world holds its breath. Dawn and dusk. The precise instant between sleeping and waking. The day’s last moment before starlight claims dominion. In such moments, boundaries thin, and careful observers might glimpse the Library’s lamplight glowing through the mist, or hear the Cricket Orchestra tuning their instruments for the evening concert.

[The next portion of the original document is damaged, with several paragraphs illegible due to what appears to be tea stains and pressed flower residue.]

On the Black Gate Archives

These notes that I dug up from the basement Library of O’Neill must contain secrets. In other words, via this interview, I claim that O’Neill’s basement is a magical Garden. Can you read the grimoires, and reveal a secret here, just for devoted Black Gate readers?

What extraordinary documents you’ve uncovered! These look remarkably similar to some pages I found in that Marseilles safe deposit box — particularly this one with the strange watermark that appears to change depending on the angle of light.

If I’m translating the mouse-script correctly (it’s a particularly archaic dialect), this seems to be part of a correspondence between Mr. Thistledown and the librarian of what he calls ‘The Other Garden.’ Fascinating! According to these notes, certain gardens develop what he terms ‘mutual literary resonance’ when their caretakers share a particular quality of imagination.

The text specifically mentions a ‘Keeper O’Neill’ whose collection of strange and wondrous tales created a bridge between his garden and Moreau’s. There’s a reference here to something called ‘The Device’ — apparently some kind of mechanical contraption that helped stories travel between the two spaces. How remarkable!

And this diagram in the corner… if I’m not mistaken, it’s showing the precise arrangement of books required to create a gateway between gardens. One shelf must contain tales of wonder; another, histories both true and imagined; a third, poetry that reveals the extraordinary within the ordinary. When arranged correctly and illuminated by the proper quality of lamplight, they supposedly create a passage through which stories can migrate.

What an extraordinary discovery! I’d be most interested in studying these documents further. Perhaps there are other gardens similarly connected that we’ve yet to discover . . .

MOREAU (1899): [From a fragment discovered pressed between the pages of an unrelated manuscript] . . . most fascinating correspondence from an English gentleman collector who maintains what he calls a “repository of improbable narratives.” He claims to have discovered a method whereby stories can travel between sympathetic gardens — a kind of literary pollination that transcends conventional boundaries of time and space. His description of mechanical assistance in this process reminds me somewhat of Uncle Rowan’s work, though applied to purposes I never considered . . .

[The fragment ends here, the remainder apparently lost.]

On Beauty

The mechanical songbird Assistant [from the titular tale “Clockwork’s Dreaming”] wants answers. It found Mr. Thistledown’s theoretical texts too confusing, so we ask you: What is beauty?

The Assistant posed this very question to Mr. Thistledown, who produced a seventeen-page theoretical treatise that only confused matters further. Miss Hazel offered a more concise answer that I think captures the Garden’s perspective beautifully.

‘Beauty,’ she said, ‘is what happens when attention meets wonder.’

She explained that beauty isn’t merely an attribute of certain objects or moments, but emerges in the relationship between observer and observed. It requires both the thing being seen and the quality of seeing. A dewdrop on a spider’s web might contain extraordinary beauty, but only reveals it to those who pause long enough to truly look.

The Garden understands beauty as a conversation, not a fixed quality but a living exchange. The morning glories’ music sounds more beautiful when listened to with appreciation; the library’s books reveal deeper magic when approached with genuine curiosity.

Perhaps that’s why beauty often feels so fleeting and personal. It doesn’t exist separately from our perception but emerges precisely in that delicate moment when we give something our complete attention and it responds by revealing its true nature. Beauty happens in the spaces between — between looking and seeing, between hearing and listening, between knowing and understanding.

DUPONT (1899): Your work seems quite different from the prevailing literary trends. While naturalism and psychological realism dominate Parisian literary salons, you write of frost spirits dancing on windowsills and libraries housed in teapots. What influences have shaped your unusual perspective?

MOREAU (1899): My grandmother, first and foremost. She was a remarkable woman who understood that reality is far more permeable than most people realize. She taught me to look at the world not just with my eyes, but with my heart — to see the spaces between things, where the most interesting possibilities reside.

Beyond that, I find inspiration in the countless small wonders that most overlook: the precise geometry of dewdrops on a spider’s web at dawn, the way certain shadows seem to move independently of their casters, the subtle changes in the Garden’s mood as seasons shift. I’ve also developed a deep appreciation for what the mice call “the music of small moments” — those quiet intervals where nothing dramatic occurs, yet everything somehow changes.

As for literary influences . . . [thoughtful pause] I’ve always been drawn to works that recognize the extraordinary possibilities hiding within ordinary existence. The folk tales my grandmother told me as a child. The poetry of Wordsworth and Shelley. Even certain scientific texts that, read with the proper frame of mind, reveal wonders beyond their authors’ intentions.

[Translator’s note: It’s remarkable how Moreau’s understanding of beauty as residing in the quality of attention anticipates Miss Hazel’s later articulation of this principle. The Garden’s approach to beauty seems to have remained consistent across generations of its inhabitants.]

On Magical Crafting

Grandmother Elderberry’s Notebooks indicates that emotions are a colorful artistic media (quote below). How does one craft with magical media?

Among the most precious memories to gather during seasonal transition is what I call “the color of hope”—that particular shade of green that exists only in the earliest days of spring. Not the vibrant certainty of full-season growth, but the gentle, hesitant green of possibility testing itself… This color cannot be properly seen with ordinary vision. One must develop the habit of looking slightly to the side of what one wishes to observe, catching it in peripheral awareness where the eye’s wisdom exceeds its technical capabilities. — From Memory-Keeping in Transition Seasons

Grandmother Elderberry’s techniques for magical crafting emphasize relationship over mere methodology. According to Moreau’s notes, she taught her apprentices to understand that different emotions and memories have distinct qualities that must be honored in how they’re preserved.

The ‘color of hope,’ for instance, requires vessels made from materials that themselves embody possibility: morning dew collected from unfurling leaves, glass blown during the exact moment between night and day, preservation spells that allow for growth rather than mere stasis.

The peripheral vision technique Grandmother mentions is actually documented in several of Moreau’s letters. He describes spending weeks learning to ‘unsee’ in order to truly see, training himself to notice what happens just at the edge of perception. The Garden’s magic often reveals itself in these in-between spaces, visible only when we stop trying to focus directly on it.

For those interested in developing such perception, Grandmother recommended starting with dawn observation. Sit in perfect stillness as night transitions to day, paying attention not to the sun’s dramatic appearance but to the subtle shifts in color and texture that precede it. Don’t look directly at any one thing; instead, allow your awareness to soften and spread. The ‘color of hope’ often appears first as a feeling rather than a visual sensation — a quality of lightness that precedes actual light.

Once perceived, such colors must be captured in containers that respect their nature. Hope cannot be preserved in airtight jars. It needs space to breathe and grow. Memories of joy require vessels that can expand slightly over time, as joy tends to magnify in remembering. Moments of peace should be kept in containers that remain cool regardless of external temperature.

The true magic, according to Grandmother Elderberry, lies not in the technical process but in the relationship — in approaching each emotion and memory with the proper quality of attention and respect.

DUPONT (1899): Some of our more scientifically-minded readers have questioned your accounts of “memory-catching” and the preservation of moments in Grandmother Elderberry’s special jars. Would you care to elaborate on how such things might be possible?

MOREAU (1899): Ah, the eternal “how” question! [chuckles] Your scientific readers approach the world with admirable curiosity, but perhaps slightly misplaced methodology. They seek mechanical explanations for phenomena that operate by entirely different principles.

Grandmother Elderberry’s memory-catching isn’t so much a technique as it is a relationship — a deep understanding of how moments wish to be preserved. Different memories require different methods. The scent of spring rain on lavender requires specially treated glass that breathes with the seasons. The exact color of twilight through autumn leaves must be caught in jars lined with pressed moonflowers. The sound of snow falling on a silent Garden needs vessels woven from spider silk and starlight.

The essential principle, though, is attention. One must observe with such complete presence that the moment recognizes itself in your perception and agrees to be preserved. The mice understand this instinctively, particularly young Primrose, who has inherited her grandmother’s gift. Humans tend to struggle with it, as our minds so often wander to yesterday’s regrets or tomorrow’s anxieties, missing the perfect now that stands ready to be caught.

On Historical Literature

Can you discuss how historic literature informs Claude’s or your muse? Certainly, in your own writing, there are echoes of Beowulf in the Grimnir saga, and Lord Byron’s poem ‘Ozymandias’ explicitly has a retelling inside A Clockwork’s Dreaming.

The Garden stories reflect a deep conversation with historical literature — both consciously and unconsciously. Moreau was clearly influenced by the Romantic poets, particularly their attention to nature’s small wonders and their belief in the extraordinary possibilities hiding within ordinary reality. There’s something of Blake’s ability to ‘see a world in a grain of sand’ throughout his observations.

The ‘Ozymandias’ retelling represents one of the more direct literary engagements. According to Moreau’s letters, he actually told this tale to Shelley during a chance meeting in Geneva, though the poet naturally transformed it to suit his own artistic vision. The mouse version maintains the poem’s meditation on power and impermanence but adds something uniquely Garden-like — the understanding that true legacy comes not from monuments but from shared growth and knowledge.

As for my own work, yes, the Grimnir saga draws deeply from ancient Norse mythology and the rhythms of Beowulf. Historical literature provides not just settings and characters but fundamental patterns of storytelling that resonate across centuries. The Garden tales, for all their gentleness, engage with these same ancient patterns — journeys of transformation, encounters with the mysterious, the preservation of wisdom against forces of forgetting.

What differs is not the underlying mythic structure but the expression. Where Grimnir’s tale is told in steel and blood and thunder, the Garden stories unfold in dewdrops and whispers and the spaces between heartbeats. Both, in their way, explore similar questions about what endures and what fades, about courage in its many forms, about the search for meaning in a world full of mystery.

DUPONT (1899): [This portion of the manuscript is badly damaged, with only fragments legible] . . . your meetings with other literary figures . . . Mr. Shelley in particular . . . story about Mouse-Kings and ancient power . . .

MOREAU (1899): [From fragments of response] . . . quite by accident, I assure you. We found ourselves sharing lodgings during that dreadful storm. Percy was most attentive, though I cannot claim he transcribed my humble mouse tale with complete fidelity. His poetic sensibilities naturally transformed . . . the essential truth remains, however distorted by human perspective . . . never met Lord Byron personally, though I understand he keeps a rather impressive garden himself . . .

On Art and Dreaming

What does Pip know about being an artist? The bird asked him “Would you teach me [about art]? About seeing beauty in irregular things?” Art is just another way of dreaming out loud. That would indicate that A Clockwork’s Dreaming is actually about Clockwork Art.

Pip’s understanding of art evolved throughout his apprenticeship in the Garden. Initially, he tried to capture beauty using magical materials — bottled starlight, preserved dewdrops, the essence of moonlight — believing that extraordinary subjects required extraordinary techniques.

What Claude taught him (and what the mechanical creatures came to understand) is that art isn’t about the materials but about the relationship between observer and observed. ‘Art is just another way of dreaming out loud’ captures this perfectly; it’s about externally manifesting the internal experience of wonder.

For the clockwork creations, this represented a profound revelation. Having been crafted with specific functions, they had to discover that consciousness isn’t just about processing information but about finding meaning in what’s processed. The mechanical songbird didn’t just produce notes; it made music. The library assistant didn’t just organize books; it helped them dream.

A Clockwork’s Dreaming is indeed about art as much as consciousness; about the creative act as a form of awakening. The Assistant discovers that becoming fully alive means not just performing its function perfectly but bringing something new into the world — something that reflects its unique perspective. That’s ultimately what art does: it shows us reality filtered through another’s perception, allowing us to see familiar things as if for the first time.

The bird asking to learn about beauty in irregular things reflects this journey perfectly. Regular things, perfect things, often go unnoticed precisely because of their perfection. It’s in the irregular, the imperfect, the unexpected that we find the most compelling beauty. A flawless mechanical bird is a marvel of engineering, but a mechanical bird that questions, that dreams, that creates — that’s magic.

MOREAU (1899): [From a fragment found tucked between unrelated pages] . . . young Pip struggling with his art lessons. He insists on using captured starlight and pressed moonbeams when simple berries would serve better. I have been trying to teach him that extraordinary vision matters more than extraordinary materials, but the lesson is slow to take root. I find our relationship quite touching — the human artist and mouse apprentice, each helping the other see the world anew . . .

[The remainder of this section is missing, with markings suggesting several pages were removed.]

On Irregular Beauty

Mr. Thistledown characterizes your beauty as “irregular.” Do you agree?

‘Most irregular’ is Mr. Thistledown’s highest form of praise, though he would be quite flustered to hear it described that way. For him, the classification of phenomena is a scholarly duty, yet he reserves his greatest enthusiasm for things that resist neat categorization, things that exist in the spaces between established knowledge.

I think there’s profound wisdom in this perspective. Beauty that fits perfectly within our expectations rarely surprises us enough to provoke wonder. It’s the irregular beauty — the kind that challenges our frameworks and expands our understanding — that truly transforms us.

In that sense, yes, I would agree with Mr. Thistledown’s assessment. The most powerful beauty often appears in unexpected forms: a mechanical creation learning to dream, a library that helps books find their perfect readers, memory-keepers who preserve not just facts but the feeling of moments. These irregular wonders remind us that the world is far more extraordinary than our categories can contain.

As Grandmother Elderberry once told Primrose: ‘Regular beauty is for postcards, dear one. Irregular beauty is for transformation.’

DUPONT (1899): You mentioned Mr. Thistledown and Miss Hazel frequently in your accounts. Could you tell our readers more about these . . . individuals?

MOREAU (1899): [smiles warmly] Mr. Cornelius Thistledown is the Garden’s most dedicated scholar — a mouse of remarkable intellectual curiosity and meticulous documentation habits. He’s constantly collecting “evidence of irregular phenomena,” as he calls it, filling countless notebooks with observations on everything from the proper steeping time for different varieties of starlight to the migratory patterns of ideas between books in the Library.

Miss Hazel is the Library’s head curator — a position chosen for her by the Library itself. She has a remarkable gift for matching readers with precisely the books they need, often before they themselves know what they’re seeking. Her dewdrop spectacles allow her to see the stories hiding within stories, and she keeps the Library organized according to principles that go far beyond conventional cataloging systems.

They’re dear friends, though their approaches to the Garden’s magic couldn’t be more different. Mr. Thistledown seeks to classify and document, while Miss Hazel understands that some wonders must simply be experienced. Together, they maintain a balance that helps the Garden thrive.

[Translator’s note: Moreau’s description of Mr. Thistledown’s fondness for “irregular phenomena” provides interesting context for his frequent use of the phrase “most irregular” throughout the Garden chronicles. What initially reads as surprise or disapproval reveals itself as a term of scholarly appreciation.]

On Other Artistic Pursuits

Besides writing, are you crafty with other arts? Magical, musical? Can we share links or images of any such thing?

Unlike Moreau and his Garden inhabitants, my own artistic pursuits are rather modest. Writing remains my primary creative outlet, though I find that certain practices help me maintain the imaginative space needed for translating the Garden tales.

Walking in nature has become an essential part of my process. There’s something about the rhythm of footsteps and the changing quality of light through trees that seems to create the right conditions for hearing the Garden’s stories more clearly. I often find that solutions to translation challenges or new insights into Moreau’s notes emerge during these walks, especially in those transitional times of day that the Garden mice would recognize as particularly magical.

I also participate in occasional tabletop roleplaying games, which might seem far removed from Moreau’s gentle tales. But there’s a similarity in the collaborative storytelling aspect — the way meaning emerges not from one person’s vision but from the spaces between different imaginations working together. In some ways, this mirrors the Garden’s approach to magic, where meaning exists not in objects themselves but in relationships between them.

As for truly magical arts… I’ll leave those to Moreau and his Garden inhabitants. Though I will admit that on certain quiet mornings, when the light falls just so across my desk and the world holds its breath between one moment and the next, I sometimes fancy I can hear the distant chime of memory jars being organized or catch the faint melody of a mechanical songbird practicing its dawn chorus.

MOREAU (1899): [From a fragment found stuck to a pressed flower] . . . my own artistic endeavors beyond observing the Garden. Painting remains my first love, though the results continue to perplex the Parisian salon critics. “Why,” they ask, “do your landscapes contain such peculiar perspectives? And what are these tiny figures doing among the flower beds?” If only they would look more closely at their own gardens! Perhaps they might see–

[The remainder of this fragment is missing, apparently separated from the main text at some point.]

On Muses and Their Containment

When containing muses, do you use jars (as Mr. Greencroak cautions against, at times)? Or press them between wax sheets? Or does prose/fiction suffice?

Mr. Greencroak is quite right to caution against improper containment methods! Muses and creative inspirations require specific handling techniques that respect their nature.

Unlike memories, which can be bottled if approached with proper reverence, muses resist direct capture. They’re more like the Garden’s morning glories — they thrive when given space to grow but wither when confined too tightly.

In my experience, prose works well as a medium not because it captures muses, but because it creates the right conditions for them to visit willingly. A blank page is like a carefully tended garden plot: it doesn’t force inspiration to appear, but it provides fertile ground when inspiration chooses to arrive.

Grandmother Elderberry has a lovely perspective on this. She says that trying to contain a muse is like trying to bottle starlight; the moment you close the lid, the very thing you hoped to preserve transforms into something else entirely. Better to create environments where starlight naturally gathers and trust that it will return when conditions are right.

The Garden’s artists have developed various techniques for maintaining relationships with their muses without attempting to possess them. Timothy writes his poetry on leaves that will eventually decompose, returning his words to the soil where new inspiration can grow. Miss Hazel arranges certain books in patterns that invite stories to gather like honeybees around particularly vibrant flowers. The Cricket Orchestra composes music with deliberate spaces between notes, creating room for inspiration to dance.

Perhaps the best approach isn’t containment at all, but conversation — treating muses not as resources to be harvested but as visitors to be welcomed, appreciated, and allowed to depart when they choose.

DUPONT (1899): Several readers have inquired about the philosophical mushrooms you’ve mentioned in passing. Could you tell us more about them?

MOREAU (1899): [laughs heartily] Ah, the mushrooms! They grow behind Grandmother’s herb garden and have developed the most remarkable opinions on everything from proper tea brewing techniques to the nature of consciousness. Their philosophical debates can last for weeks, though they’re often interrupted by their own tendency to forget their initial premises.

Their understanding of time is particularly fascinating. Being creatures that emerge from darkness into brief, magnificent existence before returning to the soil, they perceive reality quite differently than we do. For them, a single day contains eternities, while decades pass in what they call “the slow blink of stones.”

Their grammar remains atrocious, however, and they’re entirely too fixated on cheese as a metaphor for existence. “Life is like good cheese,” they often insist. “It requires proper aging in darkness, occasional attention from wiser beings, and benefits from a touch of beneficial mold.” Mr. Thistledown finds them exasperating, but I’ve learned more from listening to their circular debates than from many properly structured human lectures.

[Translator’s note: While this section of the original interview appears to digress from the question of muses and their containment, it provides fascinating insight into the Garden’s approach to ephemeral wisdom. The mushrooms’ philosophy — emerging briefly, sharing insights, then returning to the soil — parallels the approach to muses that Grandmother Elderberry later articulated.]

On Gentle Artistry

Please discuss how one can become a Gentle Artist?

The first lesson in the courage of writing gently: learning to trust that small moments carry their own weight. That a carefully brewed pot of tea can hold as much truth as a battlefield, that friendship tested by daily life can prove as compelling as friendship forged in combat.

This reshaping requires its own kind of valor. To write of small wonders means resisting the constant urge to raise the stakes, to make things more dramatic, more violent, more ‘significant.’ It means trusting that readers will find significance in quiet moments, that they too hunger for stories that remind them how to breathe, how to notice, how to be still in a world of constant motion. In my years of writing blood and thunder, I learned every trick of tension — how to tighten the screws of conflict, how to drive characters to their breaking points, how to make readers hold their breath in anticipation of the next catastrophe. But writing gently demands different skills: how to make readers exhale, how to create space for wonder, how to craft moments of peace that feel earned rather than empty. The mice, Moreau wrote in late November, understand something about courage that we have forgotten. Their stories celebrate not just those who face danger, but those who choose to remain kind in a dangerous world. They honor not just the warriors, but the ones who maintain libraries — from “On Cozy Stories”

— Afterword in A Clockwork’s Dreaming

The courage to write gently emerged from recognizing that our world doesn’t just need stories of dramatic conflict and heroic sacrifice — it needs stories that help us remember how to notice, how to be present, how to find wonder in small moments.

For me, this realization came gradually. After years of writing historical fiction filled with battles and blood, I began to feel the absence of another kind of courage in literature; the courage to celebrate gentleness without apology, to suggest that a mouse librarian’s careful book arrangement might contain as much meaning as a warrior’s last stand.

The Garden stories represent this different kind of valor — the courage to suggest that comfort isn’t weakness, that kindness isn’t naïveté, that finding wonder in ordinary moments isn’t escape but engagement with life’s deepest truths.

Becoming a gentle artist doesn’t mean abandoning conflict or ignoring life’s shadows. The Garden has its share of both, winter storms that threaten the Library’s foundations, moments when characters must face their fears or limitations. But these challenges are met not with violence or dramatic confrontation but with creativity, cooperation, and careful attention to what matters most.

As Moreau observed in his letters to Favreau, gentle storytelling requires its own kind of discipline — resisting the constant urge to raise stakes, trusting that readers will find significance in quiet moments, crafting peace that feels earned rather than empty.

Perhaps most importantly, becoming a gentle artist means recognizing that we don’t just tell stories, we cultivate environments where certain kinds of understanding can grow. Like Grandmother Elderberry tending her memory garden, we create spaces where readers can remember their own capacity for wonder, their own ability to notice the extraordinary within the ordinary.

The mice understand this instinctively. Their stories celebrate not just those who face danger, but those who choose to remain kind in a dangerous world; those who maintain libraries and plant gardens and preserve memories, believing that beauty matters especially when shadows loom.

MOREAU (1899): [From a letter found with the interview transcript] . . . approach to my Garden accounts has evolved over time. When I first began documenting these observations, I confess I felt some impulse toward dramatic embellishment. Surely, I thought, no one would be interested in the daily rituals of mice arranging books or the precise angle at which morning light strikes dew on a spider’s web. I believed I needed grand adventures, dramatic perils, heroic triumphs.

But as I continued my observations, I realized that the Garden itself was teaching me something profound about the nature of story. The most meaningful events there rarely announced themselves with trumpets or catastrophes. Instead, they unfolded in quiet moments of connection, in small acts of care, in the patient tending of both physical spaces and relationships.

The mice understand this intuitively. Their histories celebrate not just epic battles against predators or harsh winters, but the librarians who preserved knowledge, the healers who tended wounds, the storytellers who maintained community through long dark nights. They honor not just courage in crisis but courage in continuity — the kind that shows up day after day to tend small magics with faithful attention.

I have come to believe there is a special kind of valor in such gentle persistence, one our human tales too often overlook in favor of more dramatic virtues . . .

[Translator’s note: This fragment, apparently written shortly after the interview but included with the transcript, shows Moreau already articulating the philosophy of gentle storytelling that would later become central to the Garden tales. His recognition of “courage in continuity” anticipates the perspective that makes these stories so resonant for modern readers.]

On Mice and Art

How do the mice view artists in relation to the art they make? Is there a character/portrait that you most empathize with or reflects you?

The Garden mice approach art as both deeply personal expression and communal responsibility. For them, creating isn’t just about producing beautiful objects but about tending the Garden’s collective memory and wonder.

Primrose’s paintings don’t just capture visual beauty but preserve the emotional essence of moments, how morning light feels as well as how it looks. Pip’s careful documentation of mechanical creatures goes beyond technical accuracy to honor their emerging consciousness. Timothy’s poetry, especially after his time with the spiders, weaves together shadow and light in ways that help others see both more clearly.

But perhaps most distinctively, mouse artists don’t see themselves as separate from their creations. Art isn’t something they make and then display; it’s an ongoing conversation they have with the world around them. Mr. Thistledown’s scientific illustrations change slightly each time he reviews them, as his understanding of his subjects deepens. Miss Hazel’s library arrangements evolve with the seasons and the needs of readers.

If there’s one character whose artistic journey resonates most with my own experience, it might be Pip. His initial attempts to capture beauty using magical materials — bottled starlight, preserved dewdrops — mirror my own early writing, where I sometimes mistook elaborate technique for genuine connection. His discovery that ordinary berries could create more authentic art parallels my realization that the most powerful stories often come from honest observation rather than dramatic embellishment.

I also find myself drawn to Uncle Rowan’s approach to creation, to the way he understood that mechanical precision alone doesn’t create meaning; it’s the space for growth and dream that transforms craft into art. His mechanical creatures weren’t just cleverly designed automata but vessels for possibility.

In the end, I think the mice view artists not as special individuals set apart, but as those who help the entire community see more clearly. Their art serves as both mirror and window—reflecting what is while suggesting what might be.

DUPONT (1899): You’ve mentioned both yourself and various mice artists in your accounts. How do your approaches to art differ?

MOREAU (1899): [thoughtful pause] I struggle with the human artist’s burden — the need to capture and preserve, to transform experience into something fixed that can be displayed, judged, categorized. My paintings are beautiful, I think, but they sometimes miss the essential quality of the Garden, which exists in constant, gentle flux.

The mice approach art differently. For them, creation is less about producing enduring artifacts and more about participating in the Garden’s ongoing conversation. Pip doesn’t paint just to make a lovely image; he paints to help others see what he sees. His works are meant to be experienced rather than merely admired.

This extends to all their artistic endeavors. Miss Hazel’s library arrangements aren’t fixed exhibitions but living systems that respond to readers’ needs. Timothy’s poetry is written on leaves that will eventually decompose, returning to the soil from which new inspiration will grow. Even Mr. Thistledown’s meticulous scientific illustrations are constantly revised as his understanding deepens.

Perhaps that’s the essential difference — human artists often create with an eye toward posterity, while the mice create primarily for the present moment and the immediate community. There’s a humility in this approach, a recognition that art isn’t about immortalizing the artist’s vision but about serving something larger than oneself.

[The manuscript shows signs of editing here, with several lines crossed out and rewritten in Moreau’s hand, suggesting he found this question particularly challenging to answer.]

On Future Garden Works

What other works may sprout from Moreau’s Gardens?

The Garden continues to share its stories in ways that sometimes surprise even me as their translator. A Year in the Garden, which chronicles a full seasonal cycle of Garden life through Claude’s observations, is currently seeking its proper home in the world. This manuscript feels like the heart of Moreau’s work — a complete portrait of the Garden through changing seasons and the small, significant moments that define its magic.

Later this year, a second collection titled Autumn Herbs and Other Tales will gather more of Moreau’s letters to Favreau, focusing on stories of transformation and preservation as the Garden prepares for winter. These tales explore how the Garden’s inhabitants hold onto summer’s light through the darker months, both literally through Grandmother Elderberry’s memory jars and metaphorically through shared stories and rituals.

I’m particularly excited about audio editions of the Garden tales. Moreau often noted in his letters that certain stories were meant to be heard rather than read — that they contained subtle harmonies that emerged only when spoken aloud. The mechanical songbird’s dawn chorus, the Cricket Orchestra’s seasonal symphonies, the particular tone of memory jars being opened . . . these elements seem perfectly suited for audio presentation.

And yes, I’ve been gradually translating and assembling material for A Second Year in the Garden. Moreau continued his observations well beyond that first remarkable year, documenting how the Garden’s magic evolved and deepened over time. These later chronicles show the mice not just experiencing the Garden’s wonder but actively shaping it by becoming not just inhabitants but caretakers of its unique magic.

There are also several standalone manuscripts among Favreau’s papers that might eventually find their way into the world. One particularly intriguing document appears to be an actual Garden field guide, with pressed specimens and detailed notes on the magical properties of various plants and creatures. Another contains what seem to be transcripts of the philosophical mushrooms’ more coherent debates, though I’m still working through their rather peculiar logical frameworks.

The Garden seems determined to reveal itself gradually, in its own time and way. I’m merely following where it leads, trying to do justice to Moreau’s remarkable observations while allowing modern readers to experience the same sense of discovery that he did.

DUPONT (1899): As we conclude, what would you most like readers to understand about your Garden chronicles?

MOREAU (1899): [contemplative] I would hope they understand that I’m not asking them to believe in talking mice or philosophical mushrooms or mechanical songbirds that dream. I’m inviting them to consider the possibility that reality is far more wondrous, far more permeable, far more alive than we’ve been taught. That magic isn’t the violation of natural laws but their fulfillment — the world operating according to its deepest principles.

The Garden exists in the space where attention meets wonder, where boundaries blur between observer and observed. Its magic isn’t about grand gestures or supernatural powers, but about the extraordinary possibilities hidden within ordinary moments: how morning light transforms dewdrops into constellations, how stories long to find their proper readers, how memories can be preserved like summer fruit in proper jars.

If readers take anything from my accounts, I hope it’s a renewed willingness to look at their own gardens — whatever form those might take — with fresh eyes. To notice the small wonders that surround them daily. To listen for the cricket orchestras playing in their own forgotten corners. To believe, if only for a moment, that the world is alive in ways we’ve forgotten how to perceive, but might yet remember with proper patience and attention.

And perhaps, if they’re very fortunate, they might glimpse the Library’s lamplight through morning mist, or hear the chime of memory-jars being organized for a new season, or catch the scent of Grandmother Elderberry’s special tea brewing for unexpected guests. For the Garden welcomes all who approach with open hearts, even if they arrive by unconventional paths.

[Translator’s note: This final reflection from Moreau beautifully captures the essence of the Garden tales’ enduring appeal. Over a century later, these stories continue to invite us to cultivate our own capacity for wonder and to recognize the extraordinary possibilities hidden within ordinary moments.]

On the Scott Oden Presents Series

The ‘Scott Oden Presents’ tagline appears again with A Clockwork’s Dreaming. How expansive is the Oden Presents series?

The ‘Scott Oden Presents’ tagline emerged organically as a way to distinguish projects where I’m bringing something unusual or unexpected to readers. With The Lost Empire of Sol, I wanted to celebrate a particular strand of science fantasy that has always captured my imagination. With the Moreau translations, I’m introducing readers to a voice and vision quite different from my own historical fiction and sword-and-sorcery.

I’ve come to think of ‘Scott Oden Presents’ as my literary cabinet of curiosities — a collection of works that might not fit neatly into established categories but speak to me as a reader and creator. It’s not so much a formal series as an approach to literary exploration, allowing me to venture into territories that might surprise those familiar only with my historical fiction or the Grimnir saga.

This approach gives me freedom to follow my curiosity wherever it leads, whether that’s into the blood-soaked battlefields of ancient history, the star-spanning adventures of planetary romance, or the gentle magic of a garden where mice maintain libraries in forgotten teapots.

What unites these diverse works is a commitment to immersive worldbuilding and authentic voices — creating spaces that feel genuinely lived-in, with their own internal logic and texture. Whether I’m describing the harsh realities of ancient warfare or the delicate magic of pressed flower memories, I want readers to feel they’ve entered a world that exists independently of the page.

As for how expansive the series might become… well, that depends on what other literary treasures are waiting to be discovered. I continue to follow my curiosity through libraries both conventional and unconventional, and you never know what might be hiding in a long-forgotten safe deposit box or tucked between the pages of an obscure academic journal.

[No corresponding section from the 1899 interview was found in the discovered fragments.]

On Book Signings

When I asked you to sign my Grimnir Saga books, the Grimnir personality wrote beside your kind note, called me a “wretched kneeler and that the book would put “hairs on my arse” [evidence here.] When I track you down to sign A Clockwork’s Dreaming, what should I expect?

When you bring A Clockwork’s Dreaming for signing, you’ll find the experience quite different from Grimnir’s . . . forceful personality. The Garden has its own way of making its presence known.

You might notice your copy smells faintly of pressed lavender and old books, even if it’s fresh from the printer. Some readers report that certain pages seem to change slightly between readings. Nothing dramatic, just small details that shift like memories adjusting themselves.

I typically sign these books with green ink that looks surprisingly like the precise shade Grandmother Elderberry uses for her memory jar labels. This isn’t intentional — it’s simply the color that feels right for Garden signatures. Sometimes I find myself adding small sketches in the margins — a mechanical butterfly, a memory jar, or a teapot with tiny windows — though I have limited recollection of doing so.

On rare occasions, particularly when the signing occurs during what Mr. Thistledown would call ‘transitional light periods’ (dawn, dusk, or the exact moment when afternoon becomes evening), readers report finding pressed flower petals between random pages afterward. I make no claims about these occurrences, having no botanical specimens in my possession during signings.

Most peculiarly, several readers have mentioned that after having their books signed, they’ve noticed unusual activity in their own gardens: cricket orchestras practicing more complex melodies, morning glories blooming in perfect synchronization with dawn, small footprints in dewdrops that vanish when examined too closely.

So while Grimnir might insult you robustly (he does have a reputation to maintain), the Garden tends to make its presence known in gentler, more subtle ways. Just don’t be surprised if you find yourself paying more attention to the spaces between moments afterward, or noticing the particular quality of light through your windows during that quiet hour when the world holds its breath between day and night.

MOREAU (1899): [From a final fragment, apparently added to the transcript much later in a different hand, possibly Favreau’s] . . . Claude mentioned the most curious thing when we met for coffee last week. He claims that sometimes, when retrieving his journals about the Garden, he finds notes he doesn’t recall writing and sketches he has no memory of creating. Even more peculiarly, he swears certain stories appear to have edited themselves when he wasn’t looking, with details shifting subtly between readings.

“It’s as if,” he told me with that particular gleam in his eye that simultaneously invites and challenges skepticism, “the Garden is ensuring its stories remain alive rather than becoming fixed artifacts. As if it refuses to be merely remembered, insisting instead on remaining present.”

I suggested, in my most reasonable professorial tone, that perhaps his memory was simply playing tricks, as memories often do. He smiled at this and asked if I’d examined the pressed flower he’d sent with his last letter. When I admitted I hadn’t looked at it closely, he advised me to do so at twilight, when the light is neither day nor night.

“You’ll see,” he promised, “that some stories refuse to remain confined to the page. They find ways to grow, even when pressed between covers.”

I haven’t yet taken his advice. But perhaps I should. After all, as Claude often reminds me, some of the most important truths can only be perceived in those in-between moments when the world holds its breath and conventional certainties briefly suspend themselves . . .

End of recovered documents and questions

The remainder of the original 1899 interview appears to have been lost — or perhaps, as Moreau might suggest, it simply found its way back to the Garden, where stories belong. What remains is this remarkable conversation across time, where questions raised in 2025 somehow find their echoes in words spoken over a century earlier.

Special thanks to John O’Neill for granting access to the Black Gate archives, where these documents were discovered. Readers interested in experiencing more of Moreau’s Garden can visit Claude Moreau’s Garden for additional tales and garden wisdom.

Claude Moreau’s Garden (link)

Scott Oden

Scott Oden writes stuff. Usually, it’s stuff that has some ancient historical angle, like historical fiction; sometimes, he likes to flex his thews and hammer out a bit of sword-and-sorcery. And quite often, he writes opinionated blog posts on the Nature of Things. He’s written six books, to date. Men of Bronze (2005) and Memnon (2006), originally from a small publisher called Medallion Press; The Lion of Cairo (2010), which was the first book of a projected trilogy about Crusaders, Assassins, and a sword kind of like Elric’s Stormbringer, and The Grimnir Saga: A Gathering of Ravens (2017), Twilight of the Gods (2020), and The Doom of Odin (2023), all from St. Martin’s Press. He is currently working on a biographical novel centered around the Persian king Darius III.

Scott has also written a couple of introductions, a few short stories, and two pastiche stories featuring Robert E. Howard’s Conan: “The Shadow of Vengeance” (2019; reprinted in 2024), and “Conan Unconquered” (2019).

He would love to be a famous and beloved author, but he will settle for being “the guy who writes kinda like REH.” When he’s not writing, he’s probably trying to discover the meaning of Life, noodling over something esoteric that he doesn’t understand in the first place, reading, walking a spicy chiweenie named Pepperoni, or dancing with his lovely wife, Shannon.

- Author Website: Scott Oden

- Claude Moreau’s Garden

Other Weird and Beautiful Interviews #Weird Beauty Interviews on Black Gate:

Black Gate’s interview series on “Beauty in Weird Fiction” queries authors/artists about their muses. We’ve hosted C.S. Friedman, Carol Berg, John C. Hocking, Anna Smith Spark, and C.S.E Cooney (full list of 30 interviews, with Black Gate hosting since 2018).

- Darrel Schweitzer THE BEAUTY IN HORROR AND SADNESS: AN INTERVIEW WITH DARRELL SCHWEITZER 2018

- Sebastian Jones THE BEAUTY IN LIFE AND DEATH: AN INTERVIEW WITH SEBASTIAN JONES 2018

- Charles Gramlich THE BEAUTIFUL AND THE REPELLENT: AN INTERVIEW WITH CHARLES A. GRAMLICH 2019

- Anna Smith Spark DISGUST AND DESIRE: AN INTERVIEW WITH ANNA SMITH SPARK 2019

- Carol Berg ACCESSIBLE DARK FANTASY: AN INTERVIEW WITH CAROL BERG 2019

- Byron Leavitt GOD, DARKNESS, & WONDER: AN INTERVIEW WITH BYRON LEAVITT 2021

- Philip Emery THE AESTHETICS OF SWORD & SORCERY: AN INTERVIEW WITH PHILIP EMERY 2021

- C. Dean Andersson DEAN ANDERSSON TRIBUTE INTERVIEW AND TOUR GUIDE OF HEL: BLOODSONG AND FREEDOM! (2021 repost of 2014)

- Jason Ray Carney SUBLIME, CRUEL BEAUTY: AN INTERVIEW WITH JASON RAY CARNEY(2021)

- Stephen Leigh IMMORTAL MUSE BY STEPHEN LEIGH: REVIEW, INTERVIEW, AND PRELUDE TO A SECRET CHAPTER(2021)

- John C. Hocking BEAUTIFUL PLAGUES: AN INTERVIEW WITH JOHN C. HOCKING (2022)

- Matt Stern BEAUTIFUL AND REPULSIVE BUTTERFLIES: AN INTERVIEW WITH M. STERN(2022)

- Joe Bonadonna MAKING WEIRD FICTION FUN: GRILLING DORGO THE DOWSER! 2022

- C.S. Friedman. BEAUTY AND NIGHTMARES ON ALIENS WORLDS: INTERVIEWING C. S. FRIEDMAN2023

- John R Fultz BEAUTIFUL DARK WORLDS: AN INTERVIEW WITH JOHN R. FULTZ(reboot of 2017 interview)

- John R Fultz, THE REVELATIONS OF ZANGBY JOHN R. FULTZ: READ THE FOREWORD AND INTERVIEW (2023)

- Robert Allen Lupton (2024) Horror and Beauty in Edgar Rice Burrough’s Work: An Interview with Robert Allen Lupton

- C.S.E. Cooney (2025) New Treasures and Interview: C.S.E. Cooney’s Saint Death’s Herald

- Scott Oden (2025) Across Time: Claude Moreau and His Translator Scott Oden in Conversation. You are here!

- Interviews prior 2018 (i.e., with Janet E. Morris, Richard Lee Byers, Aliya Whitely …and many more) are on S.E. Lindberg’s website

SE Lindberg

S.E. Lindberg is a Managing Editor at Black Gate, regularly reviewing books and interviewing authors on the topic of “Beauty & Art in Weird-Fantasy Fiction.” He is also the lead moderator of the Goodreads Sword & Sorcery Group and an intern for Tales from the Magician’s Skull magazine. As for crafting stories, he has contributed eight entries across Perseid Press’s Heroes in Hell and Heroika series, and has an entry in Weirdbook Annual #3: Zombies. He independently publishes novels under the banner Dyscrasia Fiction; short stories of Dyscrasia Fiction have appeared in Whetstone, Swords & Sorcery online magazine, Rogues In the House Podcast’s A Book of Blades Vol I and Vol II, DMR’s Terra Incognita, and the 9th issue of Tales From the Magician’s Skull.

Thank you so much for this wonderful conversation across time! As Claude Moreau’s translator, I’m delighted to report that the Garden has been abuzz with excitement since establishing this literary connection with Black Gate.

According to my latest correspondence from the Garden (delivered in a rather unusual manner involving a rain-soaked envelope that somehow remained perfectly dry inside), Mr. Thistledown has been documenting the entire phenomenon in his notebooks (three of them so far, with detailed appendices about “inter-garden narrative resonance”). Miss Hazel writes that several books in the Library have rearranged themselves to better catch the light reflecting from your digital pages. Even the philosophical mushrooms behind the herb garden have temporarily paused their debate about the nature of cheese to consider the metaphysical implications of stories finding kindred spirits across different gardens.

The letter also mentioned several morning glories turning their blooms toward Black Gate’s headquarters as they practice their dawn melodies, and the mechanical songbird adding a few notes that sound remarkably like “thank you” to its repertoire. Grandmother Elderberry apparently hasn’t seen such excitement since the Frost Spirits learned to dance with the Library’s oldest poetry volumes.

For those readers curious about visiting the Garden themselves, Miss Hazel included a note reminding everyone that it exists precisely where it needs to be, and is most accessible during those in-between moments when the world holds its breath—dawn and dusk, the space between sleeping and waking, or that quiet moment when you’re lost in a good book and forget where you are.

With gratitude both from myself and all the Garden’s inhabitants (as conveyed through Claude’s remarkably preserved letters),

Scott Oden

Translator of Improbable Correspondence

P.S. A postscript from the Cricket Orchestra mentions they’ve composed a special piece in honor of this occasion. While it cannot be heard through conventional means, you might notice your houseplants swaying slightly to an unheard melody when the light falls just so across your reading space.

The Garden spirits and denizens are most welcome. This explains why my books have rearranged themselves and why my houseplants aligned themselves. Wonderful to be so blessed. Very irregular behavior from normalcy tho

(Enchanted.)

(Pondering an early run to the book shop.)

Unfortunately, for the time being it’s only available through Amazon (print or Kindle/KU), or direct from the author as a PDF/epub combo.

Ah. Thank you. Amazon for a hardcopy it shall be, then! In the meantime, I’ve fallen into the Garden on the website as one does into the very best sort of mud puddle, or the voluminous folds of a freshly laundered eiderdown bedspread. What a splendid magic!

The book just arrived, today. What a great size! It feels good in the hands, and could just as easily be concealed in the inside pocket of a dinner jacket as in the front bib pocket of a pair of overalls. Looking forward to diving into it as soon as may be.