In the History of Vintage Science Fiction & Fantasy, Nothing Compares to Gnome Press

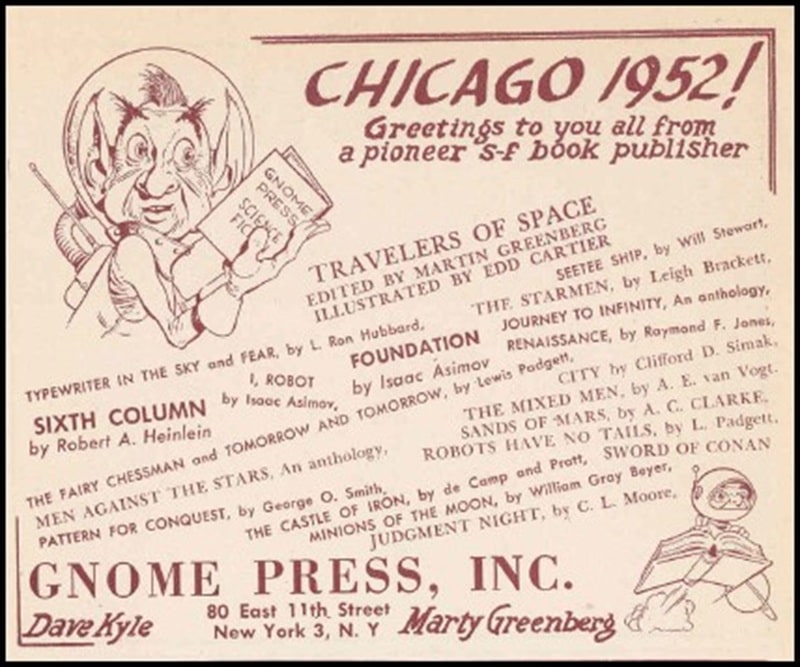

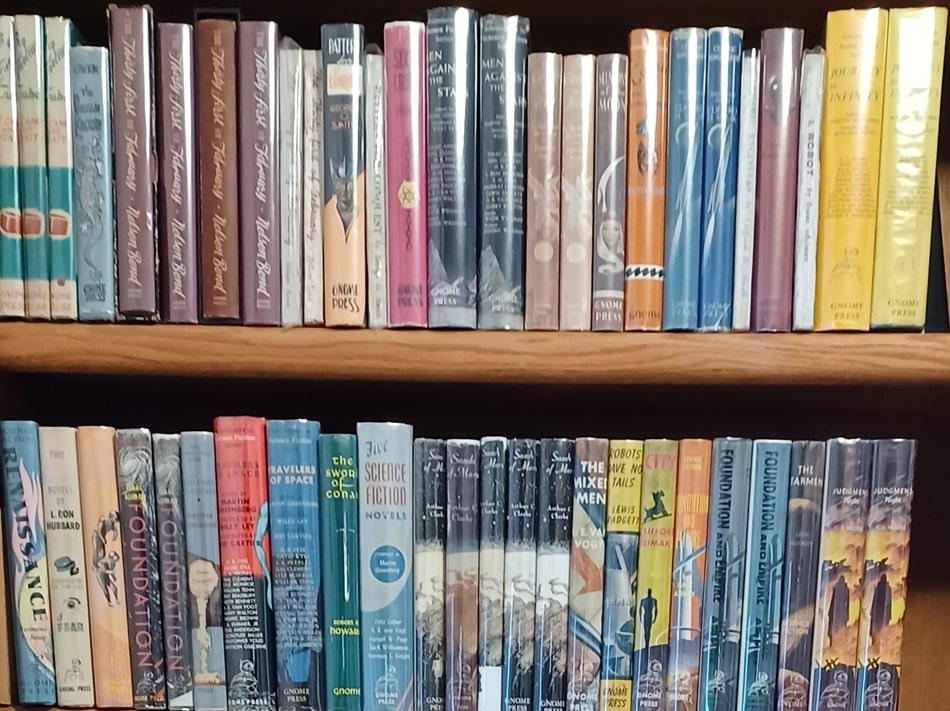

Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot and the Foundation Trilogy. Robert A. Heinlein’s Sixth Column. Arthur C. Clarke’s first three novels. The entire Conan saga from Robert E. Howard. The International Fantasy Award winner City by Clifford D. Simak. The Hugo Best Novel winner They’d Rather Be Right from Mack Clifton and Frank Riley. Books by L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt, A. E. van Vogt, C. L. Moore and Henry Kuttner, Murray Leinster, Frederik Pohl, Jack Williamson, Andre Norton, and James Gunn.

Those would be a solid core of any collection of vintage f&sf. Yet those books and dozens of others appeared in a few years from just one small publisher: Gnome Press.

Fantasy had long been a staple of what we would now call mainstream publishing but before the 1940s American science fiction was relegated to gaudy pulp magazines, critically reviled as among the lowest forms of fiction. The superweapons that emerged from World War II, especially the atomic bomb, suddenly made the field look prescient, a look into the onrushing future.

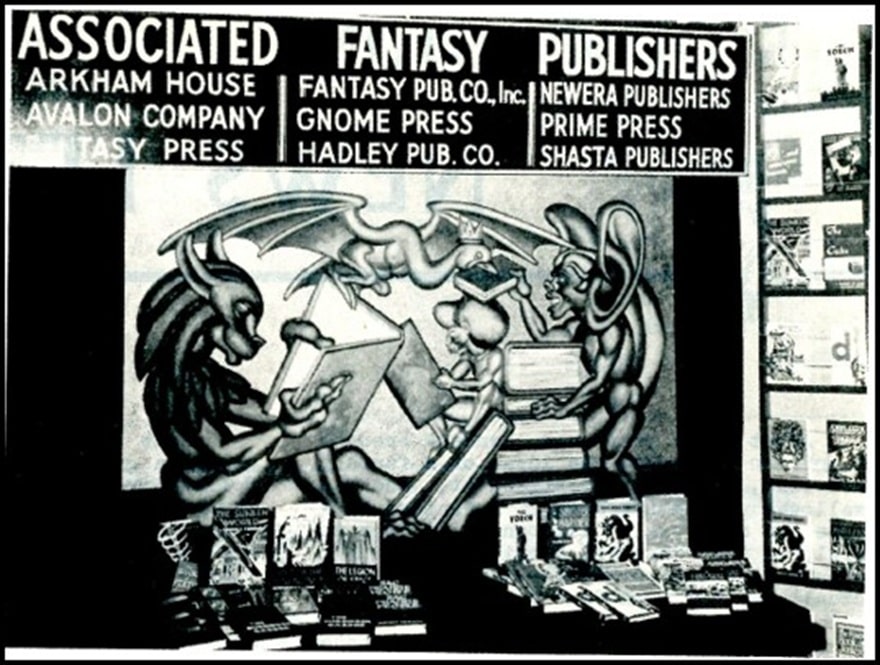

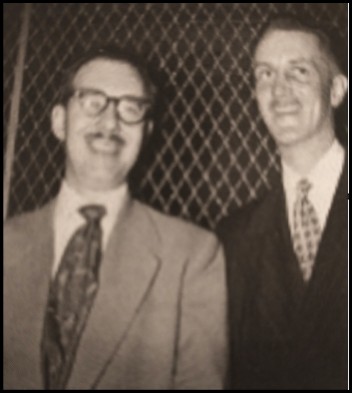

Gnome was founded in 1948 by two members of New York fandom, Martin Greenberg and David A. Kyle.

Run on the proverbial shoestring, Gnome nevertheless outpublished, outsold, and outlasted all their competitors. Greenberg had a knack for making deals and Kyle did everything else, including drawing a half-dozen covers. He was soon obsoleted by young – and cheap – newcomers like Edd Cartier, Ed Emshwiller, and Frank Kelly Freas.

The firm made mistakes – could there be a worse response to the dawn of the Atomic Age than to drop three fantasies as its first three selections? – but quickly caught on to what the public wanted. Greenberg was a disciple of John W. Campbell who, whatever is thought of him today, then towered over the field as the guru editor of Astounding Science Fiction and Unknown Fantasy Fiction magazines. Whatever he touched, sold.

Greenberg used the magazines as his Comstock Lode and cannily offered to republish story series as “novels,” suiting post-war tastes if not the labeling laws. Authors flocked to Gnome’s door, desperately wanting hardback publication.

Well, that and money. Greenberg gave them only the former. He and Kyle split the proceeds fairly. Greenberg got a salary and Kyle didn’t. (Kyle always had multiple jobs and Greenberg had a family. But still.) Nevertheless, Kyle stayed six years and Gnome lasted fourteen, with Greenberg owing money to everyone in sight. He is usually described as a charming rogue with a gift of gab. Asimov once went to him demanding money and wound up lending more.

History is never pretty. Flaws and all, nothing compares to Gnome in the history of vintage f&sf. In many ways, it is the history of vintage f&sf.

I knew nothing about Gnome when I chanced upon several titles in a used bookstore in 1980. I had seen the name in passing, but histories of the small presses were nonexistent. I found a list of all 86 titles, and dove in. A few decades later I had them all. Did I stop there? What fun would that be? Gnome produced about 75 variants, with different boards or different jackets. Nobody knows exactly how many, because new ones keep popping up. Finding all of them is essentially impossible, which means the search never has to end – the perfect collectible.

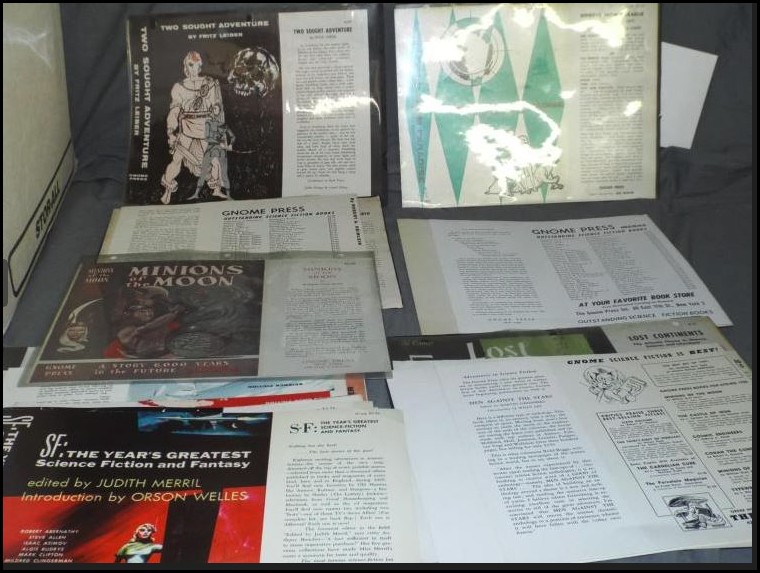

Moreover, Gnome published a variety of ephemera, from newsletters to catalogs to calendars and I set out to accumulate all that appeared on the market. I even bought the 1951 Fantasy Calendar, which was an unparalleled achievement since it doesn’t exist. (Blame Donald Wollheim.)

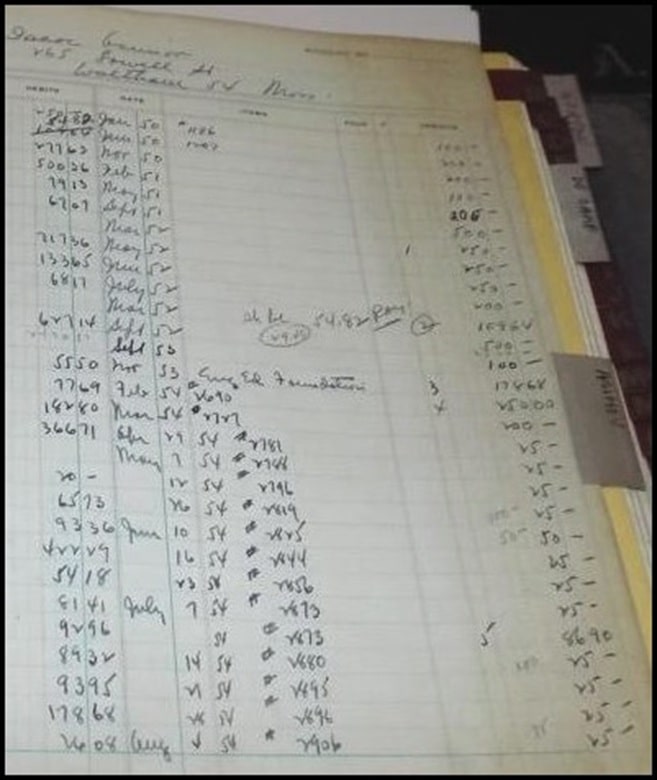

Digging for information is infinitely easier today than in 1980, yet Gnome appears to have left virtually no paper trail, an oddity for a publisher dealing every day with paper. Other than a few scraps at Syracuse University, no business records seem to have survived and not even the indefatigable Kyle bothered to talk much about his time at Gnome in the millions of words he wrote for fanzines.

Nevertheless, dogged digging over decades created a repository of everything known about Gnome. Near archaeological level scrutiny of covers, flaps, copyright pages, and back panels yielded a history of each title. Each answered question led to ten additional mysteries. Eventually I wrote an utterly unpublishable 660-page manuscript dump that would require more than a thousand images to elucidate the text.

What’s 150,000 words and 1100 images to the internet? I already owned the URL GnomePress.com. The 113 pages there now comprise the first complete bibliography of Gnome Press (by author, title, and publication date), a separate page for each title with color scans of every variant board and cover I own along with contemporary reviews and previously unknown photos of the more obscure authors, information about a range of associational items, and histories both of Gnome and the f&sf field up to the time of its founding.

For all its literally exhausting coverage, the site remains a work in progress. Gnome collectors continue to provide information that require revision to opinions I previously thought firm. If anyone reading this has even the slightest scrap they want to share, please contact me. Or just ask questions about Gnome. Anything, except how much a book is worth.

By the way, Marty Greenberg’s file copy of I, Robot inscribed to him by Asimov is listed on the internet at $50,000. If you’re the buyer, please contact me. I want to know all about you.

Steve Carper is the author of hundreds of articles on fascinating, if obscure and forgotten, tidbits of history, as well as the seminal book Robots In American Popular Culture. All of his websites are linked at SteveCarper.com.

Gnome Press is one of those legendary names from the history of SF that precedes my first contact with the field (via Scholastic Book Service). Your project to document its publications and business dealings sounds like an amazing story that deserves to be told, Mr. Carper. I just have to keep reminding myself that Gnome’s Marty Greenberg is not the other, more fiscally reliable Martin H. Greenberg, who edited many later works.

Fascinating! I was mostly aware of Gnome as publisher of those early Conan collections — I didn’t realize how much else they’d been getting up to.

[…] (6) TRAILBLAZING GNOME PRESS. Steve Carper reminds Black Gate readers that “In the History of Vintage Science Fiction & Fantasy, Nothing Compares to Gnome Press”. […]

Great stuff! Thanks for letting us know about your amazing website. I am at work and should be working, but I can’t stop clicking on famous titles to read their publication history. As soon as I get home I’m going to rush to my bookshelf and see what version of Two Sought Adventure I’ve got.

I’ve always wondered about Gnome Press, since they appear in the copyright notices of so much of the sf/f that formed my young imagination, but I rarely if ever found their books in the wild. So this stuff scratches a longstanding itch of mine.