Half a Century of Reading Tolkien: Part Two – The Fellowship of the Ring by JRR Tolkien

‘I will take the Ring,’ he said, ‘though I do not know the way.’

Frodo from The Council of Elrond from The Fellowship of the Ring (1954)

I never saw it, but once upon a time, some hippies and ancillary types were given to emblazoning FRODO LIVES on bedroom walls and the backs of denim jackets. The Lord of the Rings, the literary creation of a conservative Oxford University professor of English Literature and Language, had somehow hit a chord with the nascent counterculture after its publication in 1954/1955. I imagine, in fact, I know, there are all sorts of popular and academic works purporting to explain why this was. I’ve never been interested in them, preferring the books themselves to present the professor’s ideas.

I have my own, if not particularly original, theories. First, it’s a great adventure story featuring a small, ineffectual-seeming hero who stands up to his world’s greatest force of evil. Second, it came to be seen as a sort of rallying cry against the dark powers of the modern world. I don’t know Prof. Tolkien’s politics, though I suspect he was a small-c conservative. It’s clear he viewed the loss of tradition and the dark Satanic mills blotting out the green and pleasant England of his youth were a terrible assault on civilization (this anti-modernist attitude is an important element of Michael Moorcock’s disdain for him). Third, the counterculture’s love for anything pastoral and ante-technological was probably the most important reason for its breakout into the mainstream’s consciousness.

I never discussed it with him, but I feel confident when writing that my father liked The Lord of the Rings primarily for the first reason and somewhat for the second (he was very much a BIG-C conservative) a bit. He most definitely did not like it for the last. When I first read it all that mattered to me was that first reason. With every revisit over the ensuing decades, I’ve discovered something new. That has carried on with my most recent reread.

For the handful of uninitiated out there, The Fellowship of the Ring (comprised of two books, Book I: The Ring Sets Out and Book II: The Ring Goes South), tells of the discovery that the magic ring Bilbo Baggins found in The Hobbit is really the single most evil artifact in the world and the start of the quest to destroy it. Bilbo’s heir, Frodo, and his gardener, Sam Gamgee, at the advice of the wizard Gandalf, set out for Rivendell. Following up on his suspicions about the ring, Gandalf spent over a decade hunting down the true nature of the ring. Finally, he determined Bilbo’s ring was the One Ring, the thing by which the Dark Lord (probably the first of such figures in fantasy fiction), Sauron, could seize control of all Middle-earth.

The four hobbits encounter numerous obstacles along the road to Rivendell of increasing peril. The most dangerous is their pursuit by the Nazgûl (Ring Wraiths). They are Sauron’s greatest servants, corrupted ages ago by lesser rings he made for Men.

In Rivendell, a plan is devised to destroy the Ring by dropping it in Mount Doom, the volcano it was originally forged in and the only thing that can destroy it. A party of nine, chosen from representatives of the different races of Middle-earth and led by Gandalf, set out toward the Dark Lord’s land, Mordor. Of course, things start going wrong right away. Before The Fellowship‘s end, two of the nine companions are dead, and the rest are split into three separate groups. I’ll leave it there. If you’ve read the books, you can fill in the blanks and if you haven’t, well, go fix that giant gap in what you’ve read.

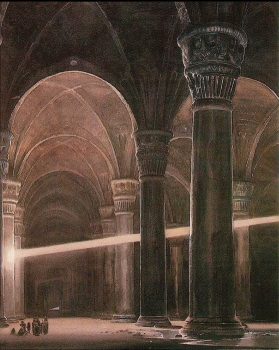

The book remains as enthralling to me as did when I first read it nearly fifty years ago. It’s filled with numerous scenes that filled me with awe on the first encounter that has never left me over the years. There are the monolithic Argonath, statues of ancient kings, standing watch over the borders of the kingdom of Gondor and the tree city of Caras Galadhon. The most striking thing was the ancient dwarven city of Khazad-dûm. I knew dwarves lived underground, but I hadn’t imagined anything like Moria. Like the nine companions, the readers are only given glimpses of Moria’s dark passageways, but they’re enough to convey its massiveness and harsh beauty.

Gandalf seemed pleased. ‘I chose the right way,’ he said. ‘At last we are coming to the habitable parts, and I guess that we are not far now from the eastern side. But we are high up, a good deal higher than the Dimrill Gate, unless I am mistaken. From the feeling of the air we must be in a wide hall. I will now risk a little real light.’

He raised his staff, and for a brief instant there was a blaze like a flash of lightning. Great shadows sprang up and fled, and for a second they saw a vast roof far above their heads upheld by many mighty pillars hewn of stone. Before them and on either side stretched a huge empty hall; its black walls, polished and smooth as glass, flashed and glittered. Three other entrances they saw, dark black arches: one straight before them eastwards, and one on either side. Then the light went out.

This time around, the outward journey of the hobbits, Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin, from the bucolic seclusion of the Shire, by degrees, into the wider, wilder world they have been largely unaware of caught my eye. The first encounter occurs while still in the Shire when they hear the sound of hooves coming along the road.

The hoofs drew nearer. They had no time to find any hiding-place better than the general darkness under the trees; Sam and Pippin crouched behind a large tree-bole, while Frodo crept back a few yards towards the lane. It showed grey and pale, a line of fading light through the wood. Above it the stars were thick in the dim sky, but there was no moon.

The sound of hoofs stopped. As Frodo watched he saw something dark pass across the lighter space between two trees, and then halt. It looked like the black shade of a horse led by a smaller black shadow. The black shadow stood close to the point where they had left the path, and it swayed from side to side. Frodo thought he heard the sound of snuffling. The shadow bent to the ground, and then began to crawl towards him.

The second and stranger encounter occurs in the shadowed depths of the Old Forest. Once, many years ago, something from the Forest had somehow pushed back against the invading hobbits. In retaliation, the hobbits burned many of the trees and built a great hedge to keep the rest of them at bay. Once inside the dark woods, the hobbits are lured and trapped by an ancient, malicious willow tree only to be saved by one of the most divisive figures in fantasy – Tom Bombabil. Tom saves the hobbits again, as they continue away from their homes, and are trapped by evil spirits infesting ancient barrows. Their experience in the barrows gives visions to the hobbits, impressing on them the depths and width of the world outside their cozy borders.

This brings me to the second thing I paid more attention to on this reading: the moments of mystery and strangeness. Some hate Bombadil because he’s too frivolous. Others maintain he was just jammed into the story because Tolkien, who’d created the character for an earlier poem, liked him too much. I hold to the theory that for the whole first part of The Fellowship, Tolkien was feeling his way into the story, letting events grow spontaneously and I love the character, silly songs and all.

In the seemingly areligious Middle-earth (that’s a complicated bit of business for some other time, perhaps), Bombabil feels distinctly divine. He is married to the daughter of the river, “knew the dark under the stars when it was fearless – before the Dark Lord came from Outside,” and sings down the very stones of the haunted barrow. When asked about him, Tolkien responded that he was “not an important person – to the narrative” and that “he represents something that I feel important, though I would not be prepared to analyse the feeling precisely. I would not, however, have left him in, if he did not have some kind of function.” He alone, of everyone in Middle-earth, is impervious to the power of the Ring. It doesn’t work for him and he has no desire to own it. I love that there is no explanation for him, an element that doesn’t find an explanation in any of the vast history Tolkien composed for Middle-earth. To quote his wife, when asked who he is, she simply replies, “He is.”

Being swallowed alive by a willow tree, evil or otherwise, is of course fairy tale strange. The haunted barrows and the capture of the hobbits by the barrow wights are more akin to the Germanic tales that partially inspired Tolkien. Trying to cross the downs, the hobbits find themselves imprisoned within one of the barrows. It is the eeriest point in the entire book, and could easily have been lifted from some skald’s ancient tale sung by the fireside.

As he lay there, thinking and getting a hold of himself, he noticed all at once that the darkness was slowly giving way: a pale greenish light was growing round him. It did not at first show him what kind of a place he was in, for the light seemed to be coming out of himself, and from the floor beside him, and had not yet reached the roof or wall. He turned, and there in the cold glow he saw lying beside him Sam, Pippin, and Merry. They were on their backs, and their faces looked deathly pale; and they were clad in white. About them lay many treasures, of gold maybe, though in that light they looked cold and unlovely. On their heads were circlets, gold chains were about their waists, and on their fingers were many rings. Swords lay by their sides, and shields were at their feet. But across their three necks lay one long naked sword.

Suddenly a song began: a cold murmur, rising and falling. The voice seemed far away and immeasurably dreary, sometimes high in the air and thin, sometimes like a low moan from the ground. Out of the formless stream of sad but horrible sounds, strings of words would now and again shape themselves: grim, hard, cold words, heartless and miserable. The night was railing against the morning of which it was bereaved, and the cold was cursing the warmth for which it hungered. Frodo was chilled to the marrow. After a while the song became clearer, and with dread in his heart he perceived that it had changed into an incantation:

Cold be hand and heart and bone,

and cold be sleep under stone:

never more to wake on stony bed,

never, till the Sun fails and the Moon is dead.

In the black wind the stars shall die,

and still on gold here let them lie,

till the dark lord lifts his hand

over dead sea and withered land.He heard behind his head a creaking and scraping sound. Raising himself on one arm he looked, and saw now in the pale light that they were in a kind of passage which behind them turned a corner. Round the corner a long arm was groping, walking on its fingers towards Sam, who was lying nearest, and towards the hilt of the sword that lay upon him.

None of these moments make it into Peter Jackson’s film of The Fellowship of the Ring. They don’t serve the narrative thrust Jackson chose to focus on. What they do is help convey the transition of the hobbits — and the story — from the pocket world of the Shire to the real world, one beset by betrayal, ravaging armies, and supernatural evil. Taken together with the dangerous episodes, they serve as a sort of veil the hobbits, representatives of the traditional, insular England Tolkien loved, must pass through before the real quest — the one to destroy the Ring — can begin.

Which leads me to Jackson’s movie, The Fellowship of the Ring (2001). That’s in fact what started this whole undertaking. Even though I’m on record disliking the movies, I needed something on in the background while doing some work and something with swords and magic seemed the right choice. Within minutes I found my dislike bubbling up. Soon it was boiling over. The easiest solution was to just pick up the books and read them again — which I did.

The thing is, I kept watching the movie, quickly followed by the other two. It’s the closest I’ve come to really hate watching anything in my life. I’ll go into more detail when I get to The Two Towers and The Return of the King as they deviate the most from the books.

I don’t dislike the movies for things Jackson didn’t do. If Verdi can edit Shakespeare, Jackson can edit Tolkien. I understand leaving out all the things I described. While I think their elimination changes the nature of the story, removing them to speed up the film’s momentum makes cinematic sense. The movie is intended as an exciting, action-filled movie, not a travelogue. Characters are compressed or excised in service of fitting a large book onto the screen. It happens all the time, often quite successfully. And still, I dislike the movies.

My easiest complaint is with filmmaking choices. First, are the moments of slow motion. Frodo getting stabbed and an uruk-hai running along a riverbank are the two moments that jump to mind most readily. They look cheap and terrible and stand out in a movie that lavished millions on looking good. Much worse is the fight and flight through Moria which becomes increasingly computer game-like as it proceeds. There is no architectural explanation that can possibly justify the staircase that collapses as our heroes are running down it. The battle in the book is much better choreographed and makes much more sense. Jackson’s camera work is skittery and nothing ever stays in a shot long enough to make much of an impression. The interaction between the characters and CGI troll looked fake twenty-plus years ago and only more so now. There are numerous other moments of interpretation I could argue about. Jackson always chose BIGGER and BOLDER, eschewing texture, subtlety, and atmosphere.

My easiest complaint is with filmmaking choices. First, are the moments of slow motion. Frodo getting stabbed and an uruk-hai running along a riverbank are the two moments that jump to mind most readily. They look cheap and terrible and stand out in a movie that lavished millions on looking good. Much worse is the fight and flight through Moria which becomes increasingly computer game-like as it proceeds. There is no architectural explanation that can possibly justify the staircase that collapses as our heroes are running down it. The battle in the book is much better choreographed and makes much more sense. Jackson’s camera work is skittery and nothing ever stays in a shot long enough to make much of an impression. The interaction between the characters and CGI troll looked fake twenty-plus years ago and only more so now. There are numerous other moments of interpretation I could argue about. Jackson always chose BIGGER and BOLDER, eschewing texture, subtlety, and atmosphere.

Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings isn’t devoid of humor. There’s Bilbo’s speech at his party and the discovery of the petrified trolls from The Hobbit. The thing is, there isn’t any slapstick. Not a bit. By which I mean especially pan-swinging, or dwarf-tossing. It’s awful and, like the slow motion, stands out in a movie that presents itself as a serious interpretation of a serious literary work.

My greater criticism is the film’s handling of the characters. Merry and Pippin are reduced to bad comic relief, instead of the clever conspirators who prove brave enough to maim and kill several orcs before Boromir is killed. Gandalf acts like a terrified fool in one moment and isn’t clever enough to solve the riddle to open the Gates of Moria himself. Boromir is more despicable seeming on the screen, instead of a man slowly being driven to madness by the Ring.

Most egregiously, Aragorn, born of an ancient line of kings, and raised to be a king, becomes a reluctant hero on the screen. We’re told he turned from the path of kingship long ago and later he says being king isn’t his goal. Aragorn is a man who has been a hero several times during his long life prior to the book, all for the purpose of opposing Sauron and restoring the kingship of a reunited kingdom. Finally, Elrond’s sworn he may only marry his daughter, Arwen, if he succeeds in his quest to become king.

Most egregiously, Aragorn, born of an ancient line of kings, and raised to be a king, becomes a reluctant hero on the screen. We’re told he turned from the path of kingship long ago and later he says being king isn’t his goal. Aragorn is a man who has been a hero several times during his long life prior to the book, all for the purpose of opposing Sauron and restoring the kingship of a reunited kingdom. Finally, Elrond’s sworn he may only marry his daughter, Arwen, if he succeeds in his quest to become king.

Instead of channeling the great heroes and chieftains of legend, Aragorn is reduced to, using one online site’s description, emo Aragorn. It feels like Jackson was incapable of believing someone could simply be portrayed as a hero, but needed to go on some sort of journey that almost forced him into choosing to be king.

There are loads of other things I don’t like about the movie. Most, though, are matters of taste, I suppose. Neither Viggo Mortensen nor Sean Bean are physically big enough or powerful enough for their roles. I don’t like many of the costumes, and I hate the portrayal of the hobbits as country bumpkins and Frodo is too young. The worst thing in the extended edition is the elf guard at Lothlorien’s five o’clock shadow.

I do like some things. Ian McKellen looks perfect. The Shire and the much of the wilderness countryside look like how I imagine they should. Galadriel taking on a terrifying visage when she imagines what she’d be with the One Ring is as exactly disturbing as it should be. Best of all, the death of Boromir, something that doesn’t come across as grandly tragic in the book as it should, is done brilliantly on the screen. That’s about it, though.

If this all seems a bit rambling, I’m sorry. Like last month, the spirit of Tolkien overpowered any original intentions I had. The result is this wandering around how The Fellowship of the Ring struck me on this tenth, or whatever it is, reading. I think I concentrated on those early chapters because excised from the movies, they are unknown to many who’ve never actually read the books. The book is much looser and messier than the movies and maybe that’s a reason I prefer it.

Read Part One of this article series here.

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Sunday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

I’ve read the trilogy twice over the span of 30 years and confess that while they have their moments I personally think they are deeply flawed and immensely overrated but to each their own and other people clearly find much to admire (and obsess) about in the work.

That said, I think a mature, thoughtful filmmaker could have made a wonderful series of films out of the material. Unfortunately Peter Jackson wasn’t the man for the job and I think you nail it on the head with your criticism.

The films look and feel surprisingly shabby with any touch of craftsmanship undone by the inexcusable overreliance on a lot of really wobbly CGI and the kind of cartoonish action sequences that have effectively rendered modern film utterly uninvolving. Gollum in particular could and would have been far more effectively realized by an actor in prosthetics, although ironically most of the real performances (McKellen and Christopher Lee aside) themselves fall thunderingly flat. These movies cried out for a less frenetic, more stately, classical touch (with some real breathing room) which is something that has always eluded Jackson as well as seemingly all of his contemporaries.

The films may not be as awful as they would have been had Hollywood run them through the post-Bruckheimer sausage factory but whatever affection and investment Jackson had for the books still feels for naught. At the end of the day they are barely more competent and only somewhat more watchable than those George Lucas “Star Wars” prequels.

Obviously, I disagree with your assessment of the books – but then I’m completely under their enchantment. Seriously, though, I can easily see why you and anyone else dislike them.

Breathing room – that’s a great point. Even when they seem to slow down, like at Rivendell or Lorien, there’s constant movement, never a sense of passing time.

I fell into The Lord of the Rings due to a need to better understand the characters and figures of the original Dungeons and Dragons. And I loved the opening book probably the best of the 6, though I confess that I make an annual ritual of listening to Baird Searles read “The Council of Elrond” from Book 2, courtesy of the radio program, “Hour of the Wolf” (Jim Freund, host, WBAI-FM). I reacted strongly to the sense of moving from the snug, comfy Shire into the broader, wider, scarier world of Eriador and then to Mordor.

And Tom Bombadil was a central part of the movement, I felt. No wonder the Counterculture readers adopted him, in his floppy hat and his silly songs. But the depth of mystery behind him and around him made him a great vehicle to introduce that same sense to the realms into which the 4 hobbits were journeying, fraught with dangerous willow trees, deadly barrow-wights, and Black Riders. I would never skip Tom Bombadil in reading LotR, even if he is bypassed by the Council at Rivendell. And Tom’s divinity? Well, “He is”, as an answer regarding Bombadil’s nature is pretty close to “I am who am”, which answer was given to Moses, after a similar question.

I’ll have to find the Searles bit. I haven’t thought of him in ages. His Reader’s Guides were important in helping me discovers lots of great authors back in high school and college.

Tolkien denied being inspired by Exodus, but, yeah, that’s pretty close.

The most recent broadcast was the Dec. 2/Dec. 9 shows (“Hour of the Wolf” was changed to a 1-hour slot), which is available at https://wbai.org/archive/program/episode/?id=54385 (Part 1).

thank you

“Looser and messier” is an angle of approach to the books that I’ve not heard before. That’s an interesting thing to enjoy about them. I suppose it makes the books more life-like than the movies ever could be, and certainly admits the mystical and near-random far more easily.

I’ll have to go find the first poem about Tom Bombadil. Perhaps it is a part of the lore that won’t taste of ash. Hopeful!

I stand by the description, but it’s the result of writing whilst half asleep at 4am. Your comments regarding Tolkien and the war really hit the mark in The Two Towers, especially during Frodo and Sam’s trek to Mordor. Discussing that might drive out most everything else come next month’s article.

I still find the Fellowship of the Ring to be the weakest of the trilogy, but over the multiple re-reads I have come to appreciate it more. Getting everything set up was quite a challenge and Tolkien pulled it off quite well. There is also something weirdly grown-up about the book, especially the first part. A kind of understated “If I’m not back by October–which I surely will be– I’ll send you a letter by September, but don’t worry about that because I’ll be back by October. If I’m not, you need to get out of the Shire in November.” And Gandalf doesn’t come back, and sends no letter, and Frodo’s plan to move becomes a real thing.

When I was younger, the whole thing was a bit of a chore, but as I’ve gotten older it has taken on a ‘2:00am call is never good news’ kind of vibe.

Regarding Bombadil, I honestly think Tolkien put him in because he balances out Shelob– they are both ancient and powerful and mysterious, covetous of their small territory, and not interested in the ring at all.

Regarding the movie, I think Jackson did a good job on them. Yes, there are things about them I don’t like and yes, I have a list of things I’d have rather he put in, but overall I’m happy with it.

Hey, Adrian. I love your two phrases – weirdly grown-up and 2am call. Really spot on.

This time around, I saw Merry, Pippin (and Fatty Bolger) as akin to the young men you find around the hero an Edwardian adventure story. With that impression in my head, it really made me dislike Jackson’s depiction of them even more. There’s a real boys’ adventure feel to those opening chapters before the awful reality hits home.

It’s been ages since I’ve read the books (actually the last time was an audio version and even that’s been 10 plus years maybe!) The films aren’t the books (duh) but I like them well enough – I think with CGI were always going to look back years later and think it looks badly. Of the three films, I felt that FELLOWSHIP is by far the better (given how the Hobbit films turned out, it’s almost like the longer Jackson works on Tolkien the worse he gets)

Well, I do dislike Fellowship the least. It deviates the least and benefits from its novelty, something that wore out with the second film.

Lord of the Rings (including The Hobbit, The Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales) is my favorite book, full stop, and I can’t count the number of times I’ve read it over the years, ever since seeing the Rankin-Bass Hobbit cartoon in 1977.

My relationship with the PJ LotR movies is … complicated. There are a number of things he did that I deeply object to (ranging from his treatment of Faramir to, yes, his overreliance on slow motion to create dramatic impact), but when he gets it right, he gets it RIGHT. Theoden leading the charge at Pelennor Fields still gives me goosebumps.

There are moments scattered across the films I do like. The charge is grand – though I want my Rohirrim looking more like Angus McBride’s version than Alan Lee’s.

I think you’re overly harsh in your treatment of the movies; while I agree that some of the CGI hasn’t aged well, overall it’s still pretty solid with really only a couple of scenes in Moria falling down; the Cave Troll bit with Legolas and the the flight across the bridge are the obvious ones. But even with that, the fight against the Cave Troll is thrilling and intense even now. I agree that the choice to make certain characters the designated comic relief is a poor one and is a disservice to both Gimli and Pippin (I would argue that Merry is treated better) but in the context of the totality of the film it’s not such a tragic sin.

I think arguing against the casting of Mortensen or Bean based on your perception of their size is simply wrong: never do either of them come off as being anything other than very tough and powerful. (and Bean is excellent in showing his fear and torment and desire in such a human fashion)

Gandalf vs the Balrog is amazing (and the sound is marvelous with a good surround system as you here the orcish arrows whizzing past your head and ticking off the walls), Arwen & Frodo at the ford is outstanding (as is Buckleberry Ferry and the Argonath; Jackson does exceptionally well with all the scenes involving water). Rivendell looks amazing, as do so many of the key locations in the film: Moria itself looks great, even if some of the CGI in the exploration is lesser, The Shire looks wonderful, Weathertop is smartly done, Isengard is impressive and cool. The “Hero Shot” after the fellowship has left Rivendell and is heading out through the pass in the rocks is still fantastic the the characters all look amazing.

Fellowship is still my favorite of the books, and while the Bombadil stuff was I think correctly excised from what was already a long movie, the scene with the Hobbits recovering from their encounter with the Barrow Wights is a really strong one that adds some interesting lore while also translating the crew into a much more dangerous world; the encounter is very different from a magical willow-tree, and it would have been interesting to translate on the screen.

At some point they will remake the movies and do a new adaptation, I think. (and they should! let’s see a new vision and interpretation!) it will be interesting to see if they follow a similar path in terms of consolidation…or if they do more in the build up and spend more time in the Shire and do the next series of movies as each book and it’s The Fellowship of the Ring Part One: The Ring Sets Out as one film.

“Arwen at the ford with Frodo…” is when I walked out of the movie. I walked out of the second when the band of elves showed up at Helm’s Deep, and never saw the third. I can understand cutting, e.g. Tom B., but not changing.

Both are too slight and short – they’re both under six feet. I much prefer Bakshi’s animated Aragorn with John Hurt’s voice. I do not like the fight with the cave troll, again, preferring Bakshi’s spot on depiction of the fight from the book, complete with the big orc getting past Boromir and Aragorn before spiking Frodo. Ah, now filming the first half as a single movie, that would be great.