In Dreams: David Lynch: 1946 — 2025

David Lynch is gone; he died Wednesday at the age of seventy-eight, bringing one of the strangest careers in American film to an end and leaving the rest of us to try to reach a conclusion as to what it all meant.

He never made a western. He never made a romcom or a workplace comedy. He never made a “prestige” period picture. He never made a buddy movie or an action movie or a heist movie or a (straightforward) crime movie. Not for him was getting hold of a franchise and riding it until it died of thirst in the desert; he wasn’t interested in making Mission Impossible 6 and 7/8. The only things he made were David Lynch movies (as the producers of Dune found to their dismay), and those were about as far out of the mainstream of American cinematic entertainment as it is possible to get and still be permitted within the city limits of Hollywood.

I resist calling him an “experimental filmmaker” — though there is a grain of truth in the description (in the effect of his work more than in its intent) — because I don’t think he was experimenting at all; I think he had a cement-solid vision of what film was and what it could do, and he knew precisely what he was up to every single minute.

For much of the past fifty years, people have spent countless hours burning up mental calories trying to “figure out” Eraserhead, Mulholland Drive, Fire Walk with Me, and Lost Highway, which seems to me to be a waste of time (though there are worse things to do with your idle hours). David Lynch’s films aren’t Sudokus, nor are they housing tract prospectuses or blueprints for can openers or toaster ovens; they’re dreams, and if his career illustrates anything, it’s how literal and flatfooted the vast majority of films are, and how very few filmmakers utilize to any degree the extraordinary power of the medium to dissolve and reconfigure the walls of reality. (In this a goof like Ed Wood beats most of today’s A-List directors, though Wood’s surrealism was the result of ineptness rather than art.)

Lynch’s most puzzling visions stubbornly resist dissection or definitive explanation, but most of the difficulty results from seeing them as puzzles in the first place. Instead, they’re spiritual weather reports; David Lynch was a meteorologist of the soul, and though he was American to the core, his movies have more in common with European films like Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad or Ingemar Bergman’s Persona or Hour of the Wolf than they do with the more commercial work of his American contemporaries.

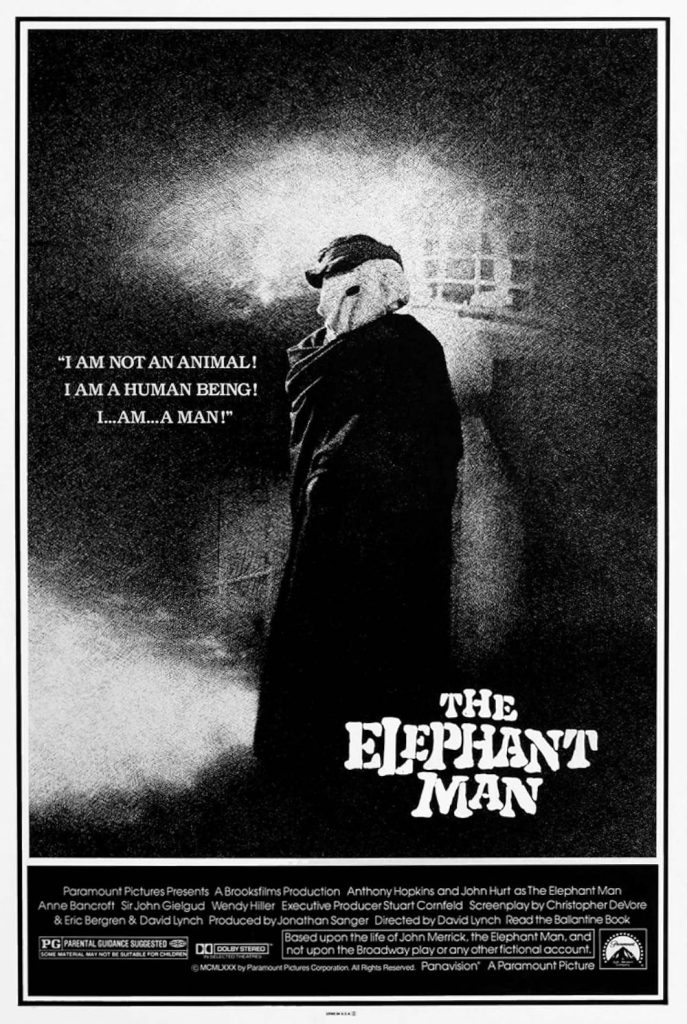

The first Lynch film I saw was The Elephant Man (1980), which was (along with 1999’s The Straight Story) as “normal” a movie as he ever made. Even then, though, I knew that this was about as far from being a conventional, heartwarming, “disease-of-the-week” weepie as you could get. The difference becomes clear when you compare the film to the box-office winners of 1980 and imagine how the directors of The Empire Strikes Back, Private Benjamin, 9 to 5, or Coal Miner’s Daughter would have handled the story of John Merrick.

Not everyone responded positively to Lynch’s oblique, uncompromisingly interior approach, especially at first. It royally ticked off Roger Ebert, for instance, who was presumably upset that The Elephant Man wasn’t the sort of thing Sydney Pollack would have given us. Ebert also hated Wild at Heart (1990), Lynch’s off-kilter, violent, Wizard of Oz-inflected love story, though how the man who wrote Beyond the Valley of the Dolls could disdain “sophomoric humor” or criticize anyone for indulging in the “cop-out” of “pop satire” is beyond me.

As time went by, though, Lynch gathered more and more approval, but many critics praised him because of the attack they believed he was mounting on the values of what used to be called “Middle America.” What else could a movie like Blue Velvet be but a savage repudiation, an unqualified exposure of the wormy rot underneath the shiny linoleum?

However, in seeing Lynch as an unqualified celebrator of subversion, these critics were missing half the boat. Lynch didn’t believe that the “real truth” of the world was a hidden corruption that was bound to come out sooner or later and overwhelm everything, or that the scrubbed, brightly-polished surface of “normality” was nothing but a lie or a hypocritical sham.

He believed in the reality and power of both the decency and the corruption. You cannot accuse David Lynch of cynicism (Ebert’s mistake), but he was certainly as Manichean as they come, seeing as he did a world poised on the razor’s-edge between darkness and light, with each constantly trying to encroach on the other’s domain. It’s his acknowledgement of both aspects of life and his rapt love of their battle, and his belief that the balance between them is subject to the merest breath, that make him such a complex — and divisive — artist.

Certainly, a man who could make both Blue Velvet, in which the placid surfaces of ordinary life conceal a subterranean hell of twisted desire and violence, and The Straight Story, where the only perversion is the decision to ride a lawn mower across the state to visit an estranged brother, is a one-of-a-kind visionary. Those two films may be Lynch’s most emblematic ones, and they are not opposites, as may appear at first glance; they are fraternal twins, one light, one dark, but standing shoulder-to-shoulder and hand-in-hand. That they both issued from the same mind and are the products of the same sensibility may be the most disturbing thing of all — they are, in fact, both the work of an Eagle Scout.

He is irreplaceable. We have other great directors — Paul Thomas Anderson, David Fincher, Kathryn Bigelow, Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino, to name just a few. But even the most adventuresome of them rarely do more than occasionally edge a toe into the territory that David Lynch spent his whole career traversing from corner to corner. He was fearlessly committed to going ever farther, digging ever deeper. He was like a legendary explorer, again and again plunging into trackless, unknown territory where anything might happen. Every film was a Lewis and Clark expedition into the wild unconscious, and the reports he brought back from those brave forays into the void revealed unbelievable terrors and awe-inspiring beauties.

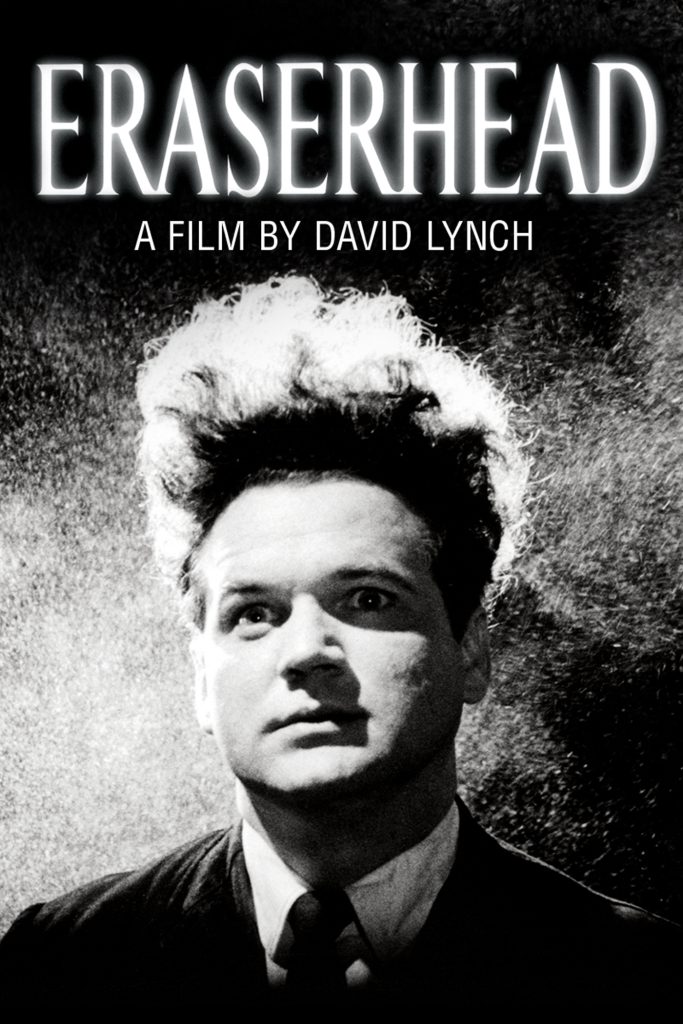

Probably like many others, when I heard of Lynch’s death the first film I though of was Eraserhead. Back in the Pleistocene (the early 1980’s, that is), if you heard about an interesting movie and wanted to see it, you pretty much had only one recourse — your local video store, and so I rented a VHS cassette of Eraserhead from the Blockbuster down the street. Then, late one night, while my wife slept peacefully in our bedroom, I turned off the lights in my living room, put the movie in the player, and was instantly plunged into an eerie, repulsive, frightening, baffling, disorienting world that was also undeniably comic and even, at times, darkly beautiful. I was clearly watching something that was not made for me — or against me, for that matter. It wasn’t made with reference to me at all, or to anyone or anything else in the world. It was wholly itself, and came to me like an artifact from another universe.

No movie has ever given me the creeps like Eraserhead did — or made me think like it did. When it was over, I sat alone in the darkness and wondered what the hell had just happened.

Old movie posters often used to be emblazoned with a cheesy boast — “Like Nothing You’ve Ever Seen Before!!” The silly slogan came true in Eraserhead; it came true again and again in everything that the enormously gifted, magnificently weird, profoundly divided David Lynch gave us. I’m sorry that he is gone, but I’m so grateful that he was here. There was only one of him, and considering the disquieting nature of his unique vision, I’m glad for that, too. I can only take so many nights like the one when I watched Eraserhead.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was A Singular Success: Fat City

While I’m more ambivalent (if not outright disappointed) by most of Lynch’s work, I am eternally grateful for the experience of “Eraserhead.” I saw it in the late seventies when it had its first showing in Michigan in a huge college lecture hall with at least 500 people. By film’s end there were perhaps 20 of us left, all standing in small groups of a handful each, our expressions and conversations alternating between stunned disbelief and giddy joy.

It was the film that exploded my ideas of what film, or any kind of art regardless of the medium, could be and forever implanted in my brain the richness of the dream narrative over the literal. I’ve always thought that Lynch and his work would have greatly benefitted had he avoided Hollywood and stayed firmly on the indie side of the fence, particularly in the eighties when there was a legitimate indie scene and appreciative audience. It’s tempting to imagine a decade’s worth of small, more intensely private Lynch film’s but the man seemed to need to live and work in the shadows of the industry. Whatever the results, the man doggedly followed his own path to the very end.

I agree with you to some extent, Byron, but from 2000 on (and sporadically before that) Lynch produced a steady stream of short, independent films that constitute a substantial body of work in themselves. But as you say, that stuff doesn’t pay the rent. (Thought it may be surprising to realize that in almost fifty years he directed only ten feature-length films.)

I’m no real student of Lynch’s films save his Baroque Dune movie. I love this and IMO the real injustice was that they didn’t give him the 6 or so hours he begged for. I’ve even heard extra footage was destroyed to thwart a “Director’s Cut” and/or a foot in the sand to fully realize it later. The time he put it out in was a boom of “Epic Movies” or very long format. Reds, Ghandhi, Last Emperor… They sold out theaters even in higher price and people bought these despite high home purchase prices. Save the guy that did the “Excalibur” movie, NOBODY could have compressed the essence of Dune into a 2.5 hour movie. That, btw, the long format (and modern SFX, a spice blow of $) is the ONLY thing the “DONE” whoops “Dune” re-re-remake has…

A fair world Lynch would have had his movie. Or a time traveler gets him the $ and a modern “Mini-Cray Supercomputer” aka a modern computer with good graphic software – and buys out the project and lets him make the Gigeresque/baroque Dune in full glory…

If I get a time machine though I’ll give the resources to Jodorowsky. This isn’t a fair world, it doesn’t deserve that mercy. Jodorowsky’s 14 hour epic. It’d be a RIOT. Dozens of them at least. I’d also take back a few polypropynol string kits (silicone String) and give lots of classic starlets boobs as big as their heads… Imagine Corman’s Women in Prison movies…Grier would have been the flat one! I might have stolen Lynch’s “Navigator” since the book/Jodo just had Space Truckers but spice let them steer around space potholes vs Plutonium Nyborg which lucky those fellas were in a universe where they didn’t ban AI…! The vision of Lynch really got to Clarketech aka Clarke’s 3rd rule where “Any science sufficiently advanced is indistinguishable from Magic”.

Dune was a famous fiasco that many people now defend (of course) as a neglected masterpiece. I don’t know that I would go that far. It’s the only film of his that Lynch disliked, that he felt wasn’t really his. It would be interesting – to say the least! – to see what Lynch’s “pure” version would have been like.

I confess the only time I saw ERASERHEAD was on a VCR at a friend’s house some time in the ’80s, and it was late and it’s just possible we had consumed a few adult beverages, and I couldn’t concentrate and really didn’t get it.

I was very impressed by BLUE VELVET, though, and I also loved at least the first season of TWIN PEAKS (and, intermittently, the rest of it) and MULHOLLAND DRIVE; and I though WILD HIGHWAY was interesting but it hasn’t stuck with me.

I ought to see DUNE, and I ought to see THE STRAIGHT STORY, but I have not.

I’m not going to apologize but I am definitely still numb by the departure of David Lynch. I’m digesting and reliving my association and then long following of his prolific art career. He gave me a energy a experience with excitement for the art experience and art expression for the out ward and inward life. I really really really appreciate you David Keith Lynch. You did it. 🎨 🎭 You are the real deal an artist in the truest since of the word. Sweet dreams. 🙏✨🙌✨🙏 Susan Wilson ’64

Beautiful article.

I was 13 years old when Twin Peaks premiered on ABC. The trailers that aired in the weeks preceding had me so intrigued, I taped the pilot on a VCR my parents had given me, as well as every episode that followed, straight through to the bitter end when the show was cancelled, a decision for which I’ve never stopped begrudging ABC.

For years to come, those VHS tapes, two episodes per tape, (SP mode) were my lifeline to another world.

I was 15 when Wild at Heart was released. Having only seen one trailer for the film (because it aired during an episode of Twin Peaks and never again) I found myself at a movie theatre in Ventura, CA a total of 7 times, watching the film during its run. Most of the time I remember being the only person in a room of empty seats.

At 17, I made it to LA to watch Fire, Walk With Me. I left the mall nearly in tears, a different person.

As a child, I didn’t fully understand his work as much as I appreciated it. That as an adult I understand it even less only deepens my appreciation for him. I wish that I could thank him for the small, impactful body of work he has left with us.

I think you’re right, Miles, that with Lynch, understanding and appreciation don’t necessarily go hand-in-hand – nor do they have to.