The Failed Giant: Five Tributes to Barry N. Malzberg

Barry N. Malzberg died on December 19. In his Black Gate obituary, Rich Horton wrote:

Malzberg was in his unique way a true giant in our field. Barry himself, in his later years, seemed to regard his career as a failure, but it was no such thing. He may have stopped publishing novels out of a feeling the publishing world wasn’t receptive to his work, but the best of what he did publish is outstanding, and thoroughly representative of his own vision.

Tributes and reminiscences have poured in over the last week, and many amplify Rich’s comments, especially in regard to both the importance of Malzberg’s work, and his embittered attitude towards the field near the end of his career. Several writers, including Adam-Troy Castro and Gregory Feeley, have generously granted permission for me to reprint their lengthy comments here, including several fascinating anecdotes.

The quotes below have been edited for length.

Jeet Heer produced an insightful and entertaining retrospective of Malzberg’s lengthy career for The Nation, titled “Novelist on a Deadline: Barry Malzberg, 1939–2024.” Here’s an excerpt.

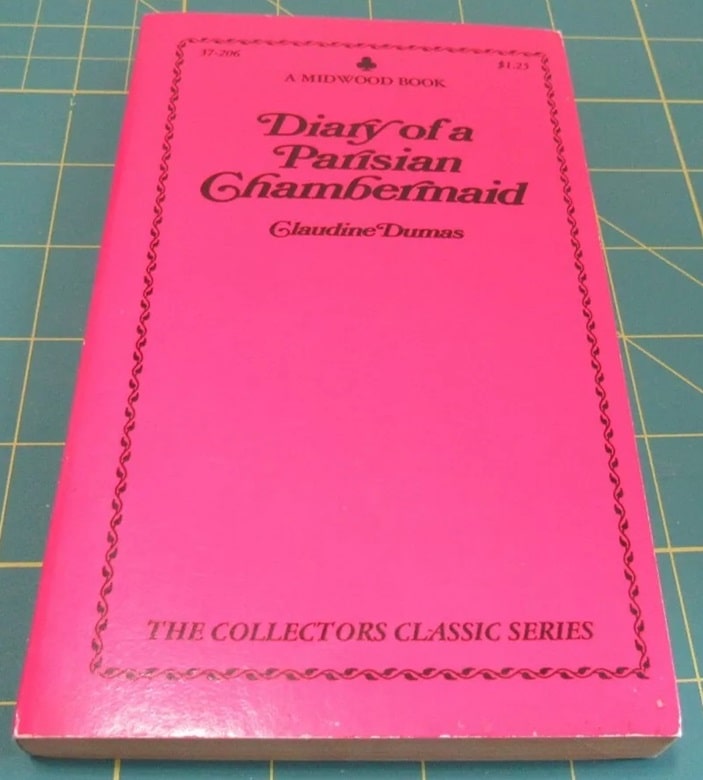

If your life absolutely depended on it, could you write a readable and publishable novel in 27 hours? In early February of 1969, that was the task an editor at Midwood books foisted on Barry Malzberg, then a 29-year-old rising star in the seedy world of the paperback quickie… On February 13, Malzberg sat down at the typewriter at 8 am and started banging away at his top rate of 60 words a minute… He finished the book the next day…

Malzberg, who died in a hospice in New Jersey on Thursday at the age of 85, flourished in the world of pulp fiction where quick writing was common: Malzberg’s friends Isaac Asimov and Robert Silverberg would both compile bibliographies of more than 500 titles. But even in that hurly-burly realm, Malzberg was a marvel. Reflecting on Diary of a Parisian Chambermaid in 2017, Malzberg told a podcast that, “in my opinion, with all deference to some writers we can name, it is the best novel written in 16 hours ever.”

In his peak decade, from 1967 to 1976, Malzberg wrote at least 68 novels and seven story collections along with scores of still uncollected stories published in many magazines and anthologies. He worked in a variety of genres, including mystery, thrillers, erotica, and adventure fiction, but his core work was in science fiction… Along with his peers J.G. Ballard, Samuel Delany and Philip K. Dick, Malzberg was a central figure in the movement of science fiction away from the external world of adventure fiction and outer space into the psychological torments and struggles of inner space…

But the struggle to write plays and stories for small literary magazines proved unappealing… In a 1979 interview, Malzberg recalled that in 1965, “I was being rejected. I was writing literary short stories and drowning in rejections and I just did not want to go any further. In October or November of that year I read in Galaxy magazine Norman Kagan’s story ‘Laugh Along with Franz.’ It was a brilliant, savage piece of science fiction, except it wasn’t science fiction at all, it was a serious, savage work of American fiction by a young American fiction writer. I shook my head as I read it and I cynically said to myself, if this son of a bitch can get away with this kind of stuff in the commercial science-fiction genre then I’ve got a future.”

By 1977, with the smash success of Star Wars, Malzberg’s somber and brooding fiction lost whatever cachet it once had. The dominant note of the genre returned to escapist adventure yarns. Malzberg, increasingly at odds with science fiction fans, wrote his last novel in 1983, although he continued to be a fecund writer of short stories.

The whole thing is worth reading. Check it out here.

John Clute shared a heartfelt reminiscence on Facebook on December 20.

Knew his work from the get-go. Finally met in the late 1980s. We were both (I guess) a bit clattery, but almost immediately found an affinity under the noise of being human, which never faded. Miss him hugely.

We both shared a sense of aftermath about science fiction; for me, from the outside, the end of sf started with the Five Point Palm Exploding Heart of Sputnik; for him it was more profound, intimate, painful. He was at the same time one of the funniest people I have ever met. Deadpan, irresistible. Passionate about the loss of the world. So I feel passionate now.

Robert J. Sawyer posted a brief tribute on Dec. 19.

The great Barry N. Malzberg has left us at the age of 85. Barry and I became friends during the many years we were both judges for the Cordwainer Smith Rediscovery Award, and when Barry retired from being the opinion columnist for Galaxy’s Edge magazine, I took his place.

Barry’s fiction was caustic and iconoclastic. His nonfiction about our genre was trenchant and heartbreaking; he knew what our field was capable of, and he decried the forces of publishing that so often kept if from fulfilling its potential.

Rest in peace, my friend.

I first heard about Malzberg’s death from Gregory Feeley, who shared the news on Facebook.

Thinking about Barry Malzberg, who died today. I was reading him in high school in 1970, when he appeared regularly in F&SF and Amazing. We corresponded for years, and talked at conventions.

I don’t think he ever read any of my fiction; by the 1980s he was largely disillusioned with science fiction, and focused his energies on the SF of his own youth. He did compliment me on my essays several times.

Barry was saturnine and frequently made predictions of an imminent disaster in the field, or perhaps in all of publishing. He was a cynic whose heart was always being broken, which I guess kind of makes him a failed cynic.

He could be awfully funny. I will miss him.

Greg expanded on his thoughts in a revealing Dec 20 piece titled A BIT MORE ABOUT BARRY MALZBERG.

Barry Malzberg was born in 1938 and grew up reading 1950s science fiction. His favorite magazine was Galaxy, which (if you knew Barry and his taste) was totally unsurprising.

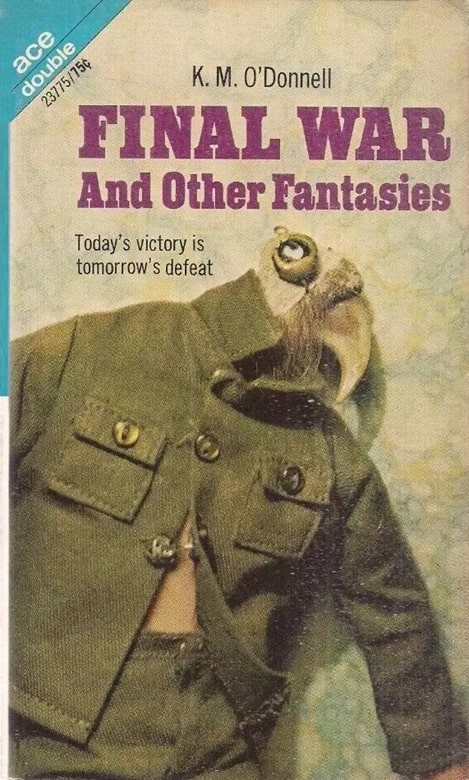

He ended up writing science fiction, but I don’t think he particularly meant to. He wrote the novelette “Final War” in the mid-sixties, and described how he could not sell it to any of the slick magazines — Playboy, Esquire, The Atlantic. Finally he sold it, under a pseudonym, “K.M. O’Donnell,” to F&SF.

Meanwhile he published some short fiction, first a story in Escapade (a third-tier men’s magazine) in early 1967, and then a short-short to Fred Pohl in Galaxy later that year. The Escapade story was published under his own name, but the Galaxy story was by K.M. O’Donnell. Barry immediately sent Pohl a sequel, which Pohl bounced, noting that sequels were usually bad ideas (which Barry admitted he knew). He went on to write a number of SF stories in 1967-68, and some appeared in F&SF and Galaxy. All were as by K.M. O’Donnell

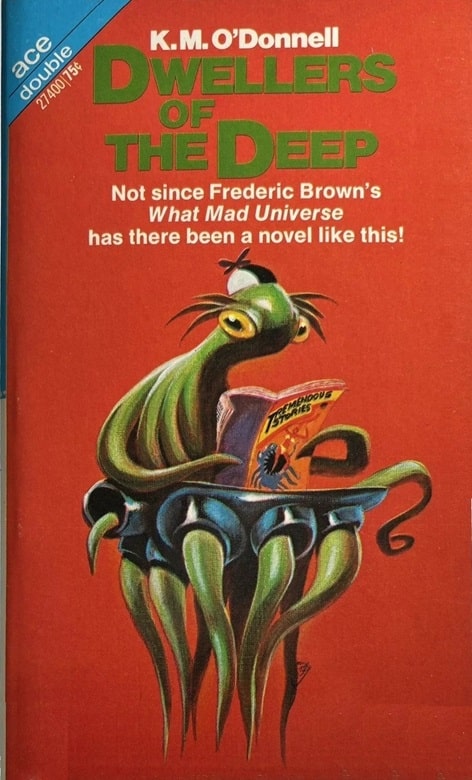

“Final War” was a Nebula finalist in the spring of 1969, and on the strength of that, Barry put together the stories he had written, including those he had not found a publisher for, and sold them to Donald Wollheim as a 129-page Ace Double, Final War and Other Fantasies. He published a second Ace Double, Dwellers [of] the Deep (113 pages), the next year.

It was in 1970 that Barry began to publish SF under his own name. (I read the first two stories, in the Harry Harrison anthology NOVA 1 and in the April F&SF, when they came out.) A few stories as “by K.M. O’Donnell” came out over the next couple years. Perhaps they had already gone out, or been sold, under that byline.

In 1971 Barry published first SF novels under his own name. He published almost entirely under his own name from that point on.

One conclusion to draw from this is that Barry wanted, very badly, to be a mainstream literary writer, and when he was driven to send the stories he could not sell in the mainstream to SF magazines, and to write some expressly for the SF market, he used a pseudonym.

When he realized that he could not sell mainstream stories (or — after a few more Olympia titles — novels) and that he could sell SF, he decided that he was going to write SF, and a lot of it. But I believe that all his SF (except for “Final War” and maybe one or two other early ones) was written in the awareness of being a failed mainstream writer and that this deeply colored the stories he wrote: their mordancy, their obsession with failure, and — this was very clear in the non-fiction pieces he wrote, most of which were of a personal nature — an unmistakable degree of self-contempt.

Gregory Feeley wrapped up his reminiscence with ONE MORE POST ON BARRY MALZBERG, also on December 20.

In the fall of 1973 Barry wrote a short piece, evidently for a fanzine that had asked for one, about the SF novel he had written in four days. The piece was apparently not published until his 1980 nonfiction collection came out, where he titled it “September 1973: What I Did Last Summer.”

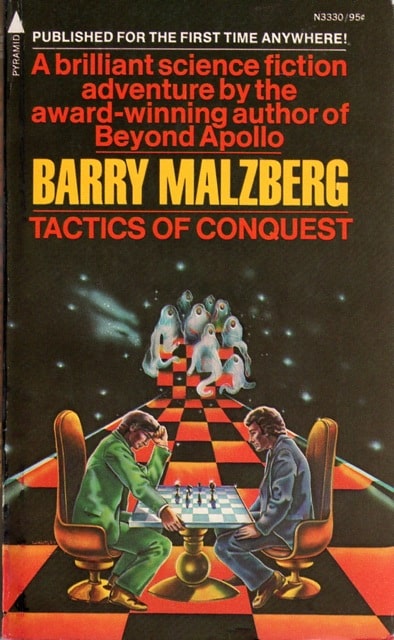

He describes how he spent the summer writing three pseudonymous novels in the Lone Wolf series for Berkley, a movie novelization, and “Tactics of Mistake,” which he produced after Roger Elwood got a contract to edit twelve SF titles for Pyramid. Elwood offered Barry $4000 for one. Elwood didn’t require even an outline, but he needed the novel quickly.

Barry accepted but insisted—it was apparently part of his paperback writer’s code — on not writing a word until he had the on-signing money in hand. By the time he got it, he didn’t have much time (although it was more than a week). Nonetheless, he took a 2600-word story he had written for F&SF and in four days turned it into the 55,000 word novel. Describing the process, he wrote: “My oh my did I pad and overload! Sentences became pages, paragraphs became chapters.” He added flashbacks and what he called “tasteful” sex scenes, explaining that sex in science fiction needed to be tasteful. (This is at once ironic — he knew that it was no longer true — and a kind of self-scorn.)

In the end, Elwood accepts the novel (Tactics of Conquest appeared in early 1974) and asks for another. Accepting, Barry decides that “I think I will expand my story ‘A Galaxy Called Rome,’ which I also wrote last summer. I can fill in on that one, too, and this story is nine thousand words, not twenty-six hundred, which makes it easier to bloat.”

He concludes by writing, “I am going to end this composition because I am very tired and you only asked for fourteen hundred words on what I did last summer and here they are and I hope my fourteen-dollar check will be payable on receipt because I really need the money. I really do. I always will. I’ll make sure of it.”

So what do we make of this? The self-loathing is so pronounced as to be a kind of performance, in which he wants to be both taken seriously and not actually taken seriously. He is certainly right that the novels were bloated. (The second one was called Galaxies, which Pyramid published in 1975, ran only 128 pages, but its proper length had indeed been those original nine thousand words.) On some level he knows that he was debauching his talent, giving readers too-short but overlong novels, and was taking advantage of editors who had trusted him to do something good. On another level, he is clearly proud of himself.

One explanation can be seen in the fact that most of the books Barry published during this period were dedicated to his wife and daughters. He was providing for them. He wasn’t going to starve in a garret writing brilliant short stories and infrequent brilliant novels like Theodore Sturgeon. He was doing to support his family.

On another level, he was clearly saying, “So, literary world, you don’t want me? You think I should be a crappy science fiction writer. All right — I will give that to you in spades.”

Barry published five SF novels in 1974 plus a collection (in addition to an unknown number of pseudonymous series books) and four in 1975 plus another collection. After that the number of book editors willing to publish him dropped off, and he began to write thrillers in collaboration with Bill Pronzini. Toward the end of the decade Doubleday published a novel and two (!) collections, but they did not go to paperback, so that was that.

Had had he spent more time on his novels and published fewer of them, would Random House and the others continued to publish him? I doubt it. Barry’s novels were strikingly similar in tone, most of them had very skimpy story lines (themes but no real plots), and he wrote repeatedly about the same things: political assassinations, astronauts going insane, and horse racing. Sometimes it was hack writers or chess players who were going insane, but the narrative tactics were almost identical.

Michael Moorcock once noted that M. John Harrison had a “somewhat narrow range,” on which he composed carefully written variations. Barry had a narrow range, but he was unwilling to make a meager living composing carefully wrought novels and stories. The two writers were similar in one respect and diametrically opposite in another.

Barry also had real problems with plotting. Nothing actually happens in most of these novels. (He was also very weak with portraying women.) He had his voice, sardonic, bleak, and often very funny, though it never really varied from one book to another. That was what his fiction offered.

Beyond Apollo was better than the story “Notes for a Novel About the First Ship Ever to Venus” and it won a prize, which allowed him to sell and write a lot of books quickly. But constructing flimsy story lines about the same miserable, obsessive characters in static situations didn’t work.

Naturally, this did nothing to allay Barry’s misery.

|

|

|

Tactics of Conquest (Pyramid Books, February 1974), Galaxies (Pyramid Books, August 1975),

and Beyond Apollo (Pocket Books, June 1979). Covers by Ron Walotsky, unknown, Don Maitz

I’d like to close this article with a pair of affectionate remembrances by Malzberg’s friend Adam-Troy Castro, the first shared on Facebook on the day he died.

Barry Malzberg has passed.

This is not a huge surprise. He was 85.

Nor is it a huge shock to the current system. Many, many years ago, I think before I had published anything, he was one of three powerful, dynamiting writers to declare publicly, and together, that they were done with science fiction. It was an attack on the infrastructure, not the potential of the field, and all three (Silverberg, Ellison and Malzberg) went back, though I think it was Barry whose public stance hurt him most — if not because he was less commercial, then certainly because he had leapt from a shorter precipice.

I think that from that point on, his output was one thin novel and a short story whenever it occurred to him, which was occasionally. Oh, and also a column for SFWA, which I will get to, cursing the necessity.

Barry was deeply aware that the publishing business included some scams that were aimed at writers of little promise, and for some time he worked, miserably, at the office of a major agent where it was his job to write encouraging letters which would encourage the wholly unpromising to send more, with additional agenting fees. This was shit work for him, and it did not thrill him.

Barry wrote dozens of novels, over a hundred I believe, some of which were absolutely terrific, but I think he won his place in posterity with two of them, in particular: Galaxies, which was self-described as not an sf novel but a series of authorial notes about a novel that could not be written; and Herovit’s World, about an sf writer who mass-produced novels about a Kirk-like character, but whose life never improved, until his sanity fractured and he became several personalities, including that of his protagonist. I think the novel a tour-de-force not specifically about science fiction, but about the writing profession, and it is nightmarish, and nightmarishly funny…

Where I am still irritated with the readership, and with much of the writership in general, was with the reaction a lot of people had to a column he wrote in collaboration with Mike Resnick, about (what we currently see as) old time editors, where the two long-in-the-tooth men talked about among other things the women in the field they had found attractive. This column erupted into a firestorm, something I fully understand, and still refer to as the time the two venerable and deeply respected figures stepped on their own dicks. I think they took as much anger as they deserved, as well as having the column taken away from them — but critically, also think they took more, in all the ways that we are now deeply familiar with, the self-righteous statements from unforgiving representatives of rage who wanted us to know that they had never even heard of Malzberg and Resnick, never had read anything they’d written, and “never would;” who then turned their rage on anyone, including myself, who agreed that the two old guys had overstepped but also held for the value of their respective bodies of work. How dare we?

I half-suspect that I might be the subject of rage just for saying this, but drawing a red marker over hundreds of works because you’re mad with the author, with full confidence that you’re missing nothing, is the act of a short-sighted idiot. (Now some of you will devote manifestos to why you’re entitled to, and please, the guy is being mourned here; don’t be an ass.)

And look, I know why people were mad at Malzberg. I even agree with them. I am, despite the assertions that will definitely accrue, fully able to admit that the two guys were acting in blind opposition to a world that had changed while they were not looking, and that the offense taken was entirely justified. But BEYOND THAT, he was in his time, one of the very best writers in the field, a prosesmith of incredible gifts, a guy who for years raged against the limitations of the literature and against the mostly-blinkered expectations of the fans, who he saw as enemies of the field’s possibilities. This was a brave position for him to take, and it cost him: I recall having a delightful lunch with him, just him and me and the actor Caryl Struycken (“Lurch”), who said nothing, at an I-Con where he was guest of honor, where he had to go to deliver his speech and later, heart-broken, reported that not a single person had showed up. I damned myself for not going. But goddamn it, he was the guy who wrote Beyond Apollo, The Time of the Burning, and the aforementioned Herovit’s World and Galaxies, and these were his monument, and what he deserved as legacy was not to have those few offensive paragraphs in the SFWA Bulletin forever pointed to as the reason he needed to be expunged and forgotten forever, but for a statute of limitations to pass so that his importance as a writer, and not as a sometimes blinkered gadfly, could pass back into relevancy…

He was a great writer, sometimes a very funny one, sometimes a heart-breaking one. He wrote at least one great novelette about the Kennedy assassination, that I cannot name now; but it is important to note that at least five of his shorter works are dancing in my brain now. He was important, I think. I deeply recommend that everybody who reads this obtain for themselves the collection, The Passage of the Light: The Recursive Science Fiction of Barry N. Malzberg, which contains a couple of novels and a scattering of short stories. “Herovit’s World” is among the contents. $14.00, still in print, worth getting…

Barry Malzberg, I salute thee. I am proud to have known you.

In a comment on a December 20 post, Adam-Troy shared a fascinating anecdote from one of Malzberg’s many convention appearances.

Barry really did think that the market for science fiction made it impossible to use it to tell adult stories. I remember thinking, “Well, if you want to be Joseph Heller, go ahead; you are that good.” And some of his novels were that good, including the two I keep singling out for special praise, Galaxies and Herovit’s World, both of which got lost in bookshelves with paperbacks that had rocket ships on the covers.

Nevertheless, when at science fiction conventions he quietly seethed that more of a fuss wasn’t made, and I clearly remember a ceremony where he came up to the big name who was sitting next to me and muttered, “I have to go, I can’t take any more of this.” Then he stormed off, and the big name, who I can no longer identify, said, “Barry doesn’t like getting a sub-ordinary audience for extraordinary stories.” And by then, based only on the evidence I had encountered in print, I would have done anything for him.

But also, I have to say, he was a great early model on the uselessness of wearing one’s professional heartbreak on one’s sleeve.

For a comprehensive summary of Malzberg’s accomplishments over a lengthy career, see his detailed obituary at Locus Online.

Regarding Adam Troy Castro’s comment about Barry storming off during a reading, I was at a Columbia University Apricon back in the 70s when GOH Roger Zelazny was doing a reading (I believe the book was Changeling, not one of Zelazny’s best). I don’t know if Castro was in the audience, or if it was a case of same reaction, different conventions, but the same thing happened.

Philip,

Thanks for the comment. Unless Adam-Troy recalls the particulars (and is inclined to share them), I suppose we’ll never know. But it could well be the same incident.

I have to agree with Mr. Castro that Mr. Malzberg’s novel, Herovit’s World, is sadly under-appreciated, even as a work that is science fiction-adjacent rather than pure sf itself. I have used it as an example of a work of fiction that demonstrates a sincere if pained love and understanding of the genre, maybe Mr. Malzberg’s most direct expression of his own relationship to the genre. I would place it alongside Ms. Atwood’s The Blind Assassin as works that deliver on the emotional joys and jeers felt by readers/lovers of pulp sf.

A Master!

Thank you for this further information on Mr. Malzberg. I hope that his family, friends, and fans can find comfort while dealing with his loss, and that he is now at peace.

It’s a… turbulent sort of legacy that he has left behind. The sort that makes a reader simultaneously heart-achy and grateful for having not been aware of it when it was happening. Unhelpful platitudes spring to mind in droves. “It is better to have loved” science fiction “and lost” control of the genre, “than to never have” written something you “loved at all.” “Judge not,” especially to the extent of categorically refusing forgiveness for public gaffs, “lest you be judged” for utter cruelty to an author once he has left us. “Never meet your heroes,” because inevitably you will never comprehend the entire story enough to keep from giving and taking wounds. “In lean times, the pelican pierces his own breast to feed his young,” and sometimes the pain never subsides.

Still, we “know a man by his fruit,” and several books that are greatly admired, along with books and short stories that are understood, is fine fruit indeed. I hope that those of us readers who never knew Mr. Malzberg will strive to esteem him by those fruits. I will certainly try.

Barry was my friend.

Here’s something I wrote about him that he loved.

https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2013/10/08/turkey-in-a-suitcase/

Here’s an exchange of emails we had.

https://fsgworkinprogress.com/2018/07/13/malzberg-reading-daniels-reading-malzberg/

I miss him.