Of “Dick Merryman” and “a Bad Stink”

One of the earliest Christmas ghost stories concludes with dismemberment and a fart joke.

Those familiar with the tradition of telling horror stories at Yuletide rather than Halloween may associate it with the late 19th and early 20th century, as those decades are considered the golden age of the traditional English ghost story, which despite its cozy label, includes tales as gruesome as anything by Lovecraft.

But it is referenced in Britain as early as 1623, with Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, in which Act 2 opens with Mamillius, the young son of Queen Hermione of Sicily, starting to tell his mother and her ladies-in-waiting a Yuletide story of “sprites and goblins” and “a man who dwelt by a churchyard.” Before he can get past that sentence, soldiers burst in accusing his mother of infidelity, and the boy, who seems to be around six or seven, is dragged offstage, to die there of shock and heartbreak. Shakespeare being Shakespeare, his play then becomes a romantic comedy.

In the US, this tradition was referenced in the 1963 hit song “The Most Wonderful Time of the Year,” with a verse about “scary ghost stories and tales of the glories of Christmases long ago.” And on British TV, it was revived by the BBC’s annual A Ghost Story for Christmas, originally broadcast between 1971 and 1978, but continued sporadically since 2005, and in the last few years, annually by Mark Gatiss.

The most famous example of this tradition was originally self-published by Charles Dickens in his 1843 illustrated novella bearing the full title A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. But although Dickens was (and remains) the most popular author of his era and A Christmas Carol is still the most famous “ghost story for Christmas,” the acknowledged master of the form is Montague Rhodes James (1868-1936), the medievalist scholar and provost of King’s College, Cambridge and Eton, who as M. R. James, published his first collection, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, in 1904.

But before publishing them, he told them to his colleagues on Christmas Eve, and to his students. Few are set at Christmas, or even mention it, none have uplifting morals, and most of his ghosts are either vengeful corpses as gruesome as anything in an EC comic book; hairy bestial demons; or crawling things that resemble octopuses, toads, spiders or insects. They don’t reform their victims, but suck off their faces, drain their blood, tear out their throats, or rip them to shreds.

That last demise is exactly what happens in “Of a Terrible Ghost”, published 109 years before A Christmas Carol and 170 before Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, which ends with a rude joke that would have probably shocked James. Although Dickens might have privately told it, the joke isn’t something he would have been likely to publish.

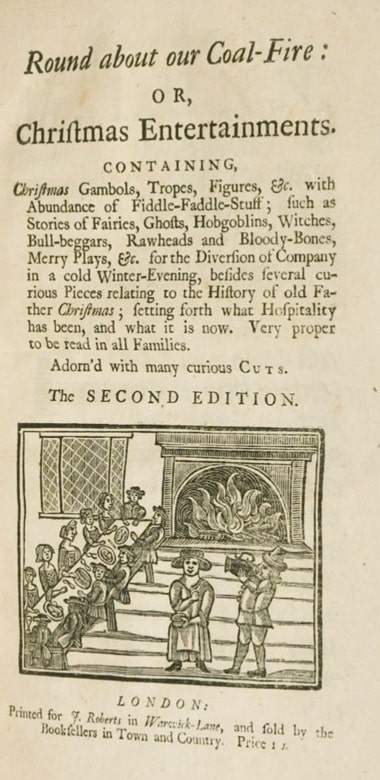

This merry Christmas yarn is part of Round Our Coal Fire, or, Christmas Entertainments, printed in 1734 by the London publisher Fenwick, and seems to have never been reprinted except in later 18th and 19th century editions of this 55-page pamphlet, which originally cost a shilling.

Cheekily attributed to “Dick Merryman,” Round Our Coal Fire boasts a lengthy subtitle promising:

Christmas gambols, tropes, figures, etc. with Abundance of Fiddle-Faddle-Stuff; such as Stories of Fairies, Ghosts, Hobgoblins, Witches, Bull-Beggars, Rawheads and Bloody-Bones, Merry Plays, & c. for the Diversion of Company in a cold Winter-Evening, besides several curious Pieces relating to the History of old Father Christmas; setting forth what Hospitality has been, and what it is now. Very proper to be read in all Families. Adorn’d with many curious [wood] cuts.

“Merryman’s” conception of what was “very proper to be read in families”, while not unusual for the 18th century, would have been considered quite improper a hundred years later, and Round Our Coal Fire only continued to be reprinted after Victoria was crowned because the cheap editions were considered either beneath official notice or a quaint relic of a fondly-remembered age.

It begins with a dedication to the “Worshipful Mr. Lun, Complete Witch-Maker of England and Conjuror General of the Universe,” whose tales of “agreeable Devils and Witches,” the author compliments for making his cousins Sarah, Dolly, and Nancy “crowd together into a Bed, in a hot Summer’s Night, and sweat to such a degree as if they had taken a Pound of Venice Treacle; so Great is the Fear they are possessed with.”

There’s then a verse prologue, with the first stanza:

O you Merry Merry Souls,

Christmas is a coming,

We shall have flowing Bowls,

Dancing, pipes and drumming.

Subsequent lines celebrate “Delicate Minced Pies to feast every Virgin,” as well as other delectables ranging from goose to sturgeon, along with “Kisses sweet as Honey,” and the promise that, at the Christmas Ball, there will be a “jolly Coupling” with “Cuckolds all-a-row” and “sweet smirking Misses.”

The first chapter is titled “Of Mirth and Jollity, Christmas Gambols, Eating, Drinking, Kissing, and other “Diversions of the Holidays.” The second describes “Hobgoblins, Raw-Heads and Bloody-bones, Buggy-Bows, Tom-pokers, Bull-Beggars, and such like Horrible Bodies.” The third offers “Witches, Wizards, Conjurers, and Such Trifles.” The fourth, “Enchantment demonstrated in the Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Beans,” which is an early version of Jack in the Beanstalk.

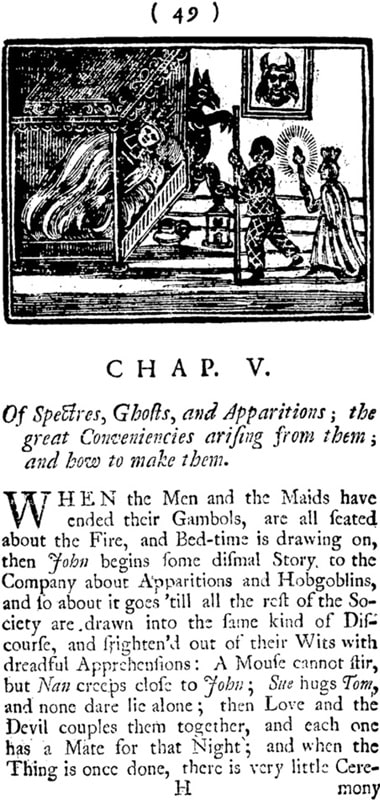

But it is in Chapter 5, “Of spectres, ghosts and apparitions; the great Conveniences arising from them; and how to make them,” that Dicky Merryman’s festive pamphlet really gets down to bloody business.

This chapter includes the tale “Of a Terrible Ghost,” which may be the earliest example of a Christmas ghost story in which the vengeful revenant is a hideous and very physical monster that gruesomely kills its victim. In fact, this toad-like apparition is reminiscent of the child-killing frog-thing in M.R. James’ “The Haunted Doll’s House.”

Here is Dick’s short, merry and ghoulish tale, which at 400 words, might be considered an early form of flash fiction. I have modernized the capitalization, punctuation and spelling to make it more readable.

Of a Terrible Ghost

There is a melancholy narrative in the Ballad of Bateman, expressing the horrible circumstances of a lady being carried away by the ghost of her true Love, who had hanged himself for her inconstancy. Read this ballad and tremble; but much more tremble at the following story.

Mr. Thomas Stringer, a gentleman of good fortune, courted the greatest beauty in his county, who received all his addresses with the fondest love and affection that could be. He seemed to be the man for her money, and a piece of gold was bent between them, as a sacred pledge of their mutual affections. But there were many more lovers that followed her daily, and by bad luck one of them, by some way or other, gained her affections.

In the meanwhile, Stringer had intelligence of it, and now and then upbraided her of infidelity; but she in a gallant way replied, that she might do what she would with her own if she thought fit, and keep what company she pleased. This answer stuck in Stringer’s stomach for a few days, until he was certified of her being false to her vow, and was well satisfied she received the addresses of man, and so poisoned himself.

But a few nights later, what a terrible figure did he make her bedchamber! His hair was nothing but serpents, his lily-white hands and his pretty little feet were become like eagle claws, he crawled like a toad along the floor, croaking as he went, and glaring eyes with horror in their looks; he had a Light all about, as he was red hot.

The lady was all affrighted by his ghastly appearance, while the toad-shaped creature was crawling up the bed, and then kissing her with his ugly mouth, spit venom in her face, and then in a hideous voice hollowed out, “Now I have caught thee, and will be revenged!”

After which the ghost with his iron claws tore her to pieces, and sent her scraps to the Devil, as just reward for her treachery. All the while this was doing, the candle, which stood on the table, burnt blue, which gives me room to think that a bad ghost and a bad stink are the same thing; for a bad stink will make the candle burn blue as a bad ghost – and then I awaked in a fright.

Ian McDowell’s last article for Black Gate was How Billy Graham’s Conan Art Got Him Fired from Fantastic Magazine.