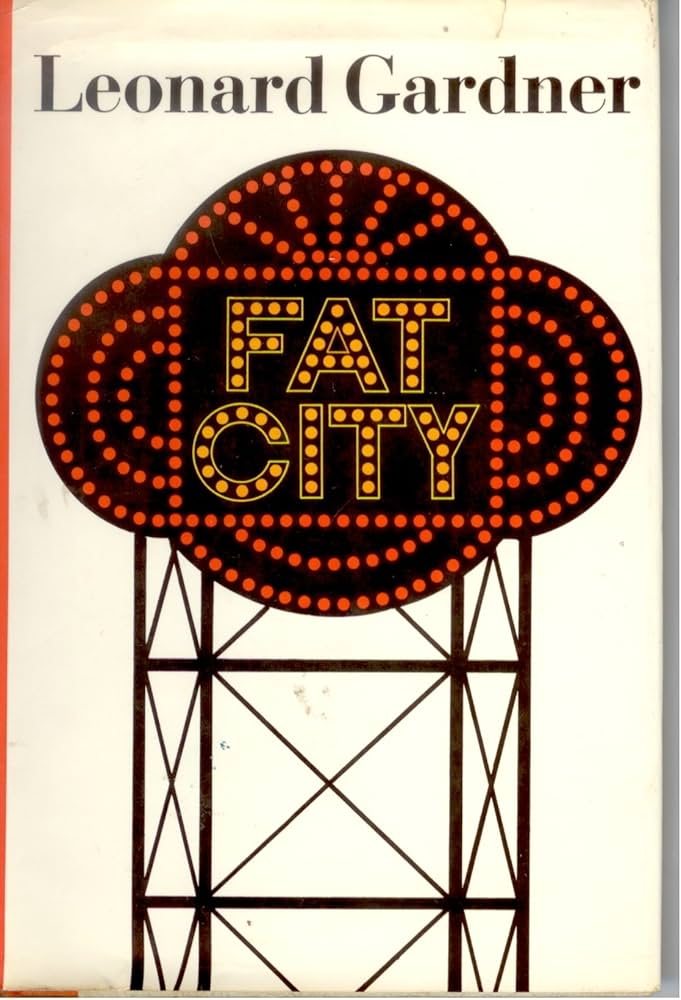

A Singular Success: Fat City

I hold people who write novels in awe. Because writing an entire book-length story is something that I could never do in a million years, I even have a measure of admiration and respect for people who write mediocre novels, so you can imagine how I feel about someone who writes a beautiful novel, a brilliant novel, a great novel; you can imagine how I feel about Leonard Gardner.

“Leonard Gardner — who’s that? I’ve never heard of him.” Well, I’m here to tell you that Leonard Gardner should be a household name, because he wrote one of the finest, most moving novels that has appeared during my lifetime; Leonard Gardner wrote Fat City.

Fat City is set in the waning days of 1959, in Stockton, California, and it chronicles the lives of two small-time boxers. Billy Tully is at the end of his career, newly divorced, washed-up and drifting into alcoholism as he moves from one seedy hotel to another, filling his days with melancholy reverie and back-breaking farm jobs. Ernie Munger is just starting out, working at a gas station during the day and fighting in four round prelims at night to support his new wife, whom he married because he’d gotten her pregnant. Billy and Ernie both dream of glory, but there is no big time here, no Fat City of wealth, fame, and success — just limited young men who win or lose for a few dollars and piss blood for weeks afterward. Ernie, still fresh and hopeful, feels “the potent allegiance of fate,” but his arc will inevitably be the same as Billy’s; the time and place and his own lack of internal resources guarantee it.

Fat City (according to Gardner, slang for “the good life”, and more pertinently, “a crazy goal no one is ever going to reach”) is a fine-grained look at a world so far removed from most of us that it might as well be set on Mars, a world of farm laborers, truck drivers, dish washers, mechanics, gas-pump jockeys, barflies, hookers, winos, warehouse workers, janitors, clerks in cheap hotels, and small-time boxers, a grubby, hardscrabble world filled with people who can’t even be described as forgotten, because to be forgotten you have to have registered somewhere, sometime, with someone.

It’s a book that is so good and so honest that it transcends the narrow confines of the “sports story”, so many of which are hampered by their scrappy underdog, two out-bottom of the ninth cliches, which is not to say that a sport can’t be a worthy subject for a serious novel. Why not? It all depends on the sensibility in charge. (Surely Bernard Malamud and Mark Harris already demonstrated that with The Natural and Bang the Drum Slowly.)

In any case, often the best books take something very narrow — sailing on a whaling ship, drifting down a river, farming, painting, dancing, fishing, playing the trumpet, soldiering — and go so deep into that particular thing that a seemingly limited subject becomes universal, is transformed into a valid (even irreplaceable, once you’re read such a book) metaphor for much more than its ostensible subject. That’s something that readers and writers have always known; as Joan Didion said of From Here to Eternity, that great book proved “that James Jones had known a great simple truth: the Army was nothing more or less than life itself.” Fat City is a book like that; in the smoke-filled arenas of Stockton, Billy Tully and Ernie Munger trade blows with what Jones called “all the overpowering injustice of the world”, injustice that can’t be changed, avoided, bought off or beaten — it can only be fought.

Fat City should be depressing, depicting as it does fruitless, frustrated lives in a bleak and cheerless setting. But Gardner’s observation of place and character is so keen, his understanding and compassion for these people so deep, his dialogue so revealing and resonant, so quirky and unexpectedly funny, his grasp of his material so firm and assured, that the ultimate effect is exhilarating. Fat City is pure pleasure to read, and it is one of my favorite books in all the world.

Fat City made a big impression when it was published in 1969, when its author was only thirty-three. It was his first novel; it earned rave reviews and was praised by heavyweights like Joan Didion (who clearly knew a great book when she read one), Walker Percy, and Ross Macdonald. Gardner seemed to be at the start of a great career.

He followed his stunning debut with just a few short pieces of nonfiction, and then… nothing. He’s still around; he worked for a while as a writer, story editor, and producer in television, primarily on crime shows (a strange vocation for a man who’s never owned a TV). He wrote the script for John Huston’s 1972 film of Fat City (one of the best movies ever made about boxing) and he did another movie script or two. One way or another, he’s managed to keep body and soul together.

But he’s never written another novel, though his sole book hasn’t been forgotten; in 2015 it was reprinted by New York Review Books Classics, and five years ago, Gardner was interviewed by The Paris Review. He was then eighty-six, and he told the interviewer that he had committed to another novel; he’s ninety-one now, and I don’t expect that we will ever see it. Apparently, he had just one fight in him, but that’s all right. As the interviewer told him, “You wrote a book that many people think is a masterpiece. That’s one more masterpiece than most people have written in the history of the universe.”

I do wonder what has kept someone with a talent like Gardner’s from following up one brilliant novel with another and another. A half-century of writer’s block? That would almost be a fate worse than death, but literary paralysis is not the impression I get from the Paris Review interview; instead, I sense in Gardner a hesitancy, a modesty, a sort of shyness even, an indefinable something that has resulted in an inability to envision himself as a real writer as opposed to a just a working-class guy from Stockton (the dusty Central Valley dead-end where he took his lumps as an amateur welterweight is his hometown) who, a long time ago, happened to write a book, in just the same way he once tended bar and worked at a skid-row gas station and did day-labor farm work.

Whatever the reason for his prolonged silence, I hope Leonard Gardner knows that he wrote a perfect book; if he had only one story to tell, he told it indelibly, and while we can regret that his success was destined to remain a singular one, we can also take some satisfaction from knowing that, unlike so many others, he at least hasn’t diluted his achievement with inferior repetitions. I don’t know why things played out for him the way they did, but I’m grateful that all those years ago, he wrote Fat City — it’s a book that’s going to be around for a long, long time. Fat City… in one way or another, we’ve all been there.

(After-the-Fact-Disclaimer: If you made it this far, you probably noticed that Fat City isn’t fantasy, science fiction, horror, or even a crime or mystery novel, which means it’s way out of Black Gate’s traditional wheelhouse. Because I love the book so much and want everyone to read it, I asked John if I could write about it, and he was generous — or addled — enough to say yes. Thank you, Boss! You made my day, if no one else’s.)

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was Taking in the Trash: Paul Cantor’s Pop Culture Trilogy

No, FAT CITY isn’t fantasy or SF, but it’s great writing and so it’s worthwhile to see it advanced here. If you didn’t know, Denis Johnson cited Gardner’s novel as the model he tried to live up when he wrote *his* first novel, ANGELS.

Yes, I should have mentioned that Johnson wrote the introduction to the NYRB paperback. (I haven’t read that intro – my copy of Fat City is the 1969 first edition.)

There are some books that you have to finish reading at the kitchen table. You have to do so in order to slide them gently to the side, to give you room to cross your arms on the table, to pillow your head there as you bask in the contented afterglow, and dream of reading the next one in heaven. Your description makes “Fat City” sound like one of those.

God, I loved this novel! Read it in the paperback edition that came around around the early or mid 1970s, when I was hoping to become a writer, and probably when the movie came out. Blew me away. The only other person I’ve known of who read it was John Douglas, the editor at Avon, whom I met just one time, in the fall of 1989. We were talking books and he mentioned Fat City. We agreed it was phenomenal, but he did admit he found it depressing. I must get a copy and reread it. Thanks for talking about it here!