Gary Gygax’s 17 Steps to Role-Playing Mastery (Steps 1 to 5)

My Dungeons and Dragons roots don’t go back to the very beginning, but I didn’t miss it by much. I remember going to our Friendly Local Gaming Store with my buddy. He would buy a shiny TSR module and I would get a cool Judges Guild supplement.

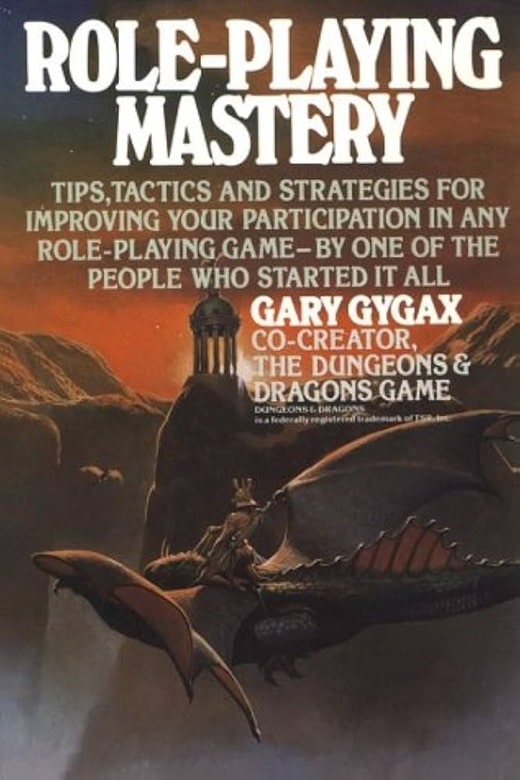

And I remember how D&D was the center of the RPG world in those pre-PC/video game playing days. And Gary Gygax was IT. It all centered around him. So, I read with interest a book that he put out in 1987, less than twelve months after he had severed all ties with TSR.

Role Playing Mastery is his very serious look at RPGing. He included the 17 steps he identified to becoming a Role Playing Master.

If you’re reading this post, you probably know that Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson co-created Dungeons and Dragons circa 1973-1974. Unfortunately, it was not a long-lasting partnership and lawsuits would ensue. While both were instrumental in creating D&D, it is Gygax who is remembered as the Father of Role Playing.

In 1987, Gary Gygax put out a book entitled Role-Playing Mastery, which gave guidelines on how to excel as a player in role-playing games. At that time, there were essentially two versions of Dungeons and Dragons. The Original, or ‘Basic’ game, had evolved under Tom Moldvay’s rules development.

Gygax, meanwhile, was focused on Advanced Dungeons and Dragons (or AD&D). They were marketed as separate rules systems and 2nd Edition AD&D would not be released until 1989.

Gygax had been pushed completely out of TSR (the company he co-founded to print the first set of D&D rules) by December 31, 1986, so he was no longer associated with D&D when this book came out. Anything BOLD, or ITALICS, is a direct quote. The rest is me, commenting on Gygax’ bold statements.

In an interview not long before he died, Gygax was asked how he’d like to be remembered and replied:

This book, which he wrote about twenty years before his death, reflects that philosophy. On a side note, he wrote a companion book that came out in 1989, Master of the Game, which focused on the Dungeon Master/Game Master side of role-playing.

They are both interesting reads; partly because he takes the subject so seriously. And bear in mind that PC gaming consisted of titles like Ultima IV, Wizardry and Bard’s Tale. Pool of Radiance, the first of the gold box series, was a year away. MMORPGs weren’t even conceived of yet (yes, I know MUDs existed).

But computer gaming was a very different world. People RPGd by sitting around a table together. And Gary Gygax suggested how they could be very good at it. As ‘nerd culture’ has become more prevalent, tabletop RPGing has become more popular again.

I wrote in the first post of a thread over on the Paizo (Pathfinder) message boards in February of 2012. It easily became the most popular discussion I’ve ‘run’ online.

I re-read Role Playing Mastery several times during the life of the thread and there’s MUCH more to it than just the Seventeen Steps. For example, this post listed Gygax’ Outline of Study for Mastery: it’s fine if you don’t have anything else to do in your life. The book talks about problem players, creating characters, making your own rules: basically, you get a chance to pick Gary Gygax’s brain.

Something that really comes through in Gygax’s book is that, regarding Mastery, he’s taking this stuff really seriously. More than any of us gamers do, and probably more than professionals in the industry as well. The concepts are interesting to read and discuss, but it’s a very specific issue he’s looking at. And it comes across as unrealistic today. So, you take the basic premise with a grain of salt.

He doesn’t exactly define Mastery, but this, from the book, seemed to narrow in on it:

As it is with other kinds of mature amusements and diversions, so it is with role-playing games: The higher the level of play, the more enjoyable the game. Simply put, mastery of role-playing is not so much an effort toward individual excellence as it is a broadening of personal knowledge, contributing to social group activity, and increasing the fun and excitement that stem from superior participation.

This is when role-playing becomes captivating. When you master role-playing, you become immersed in an activity that is peerless among leisure-time pursuits. Mastery is achieved by understanding the game system, using it fully and correctly, excelling in operation within the system, and assuring that the experience is enjoyable for all the individuals concerned.

I have found this to be an interesting read: much of it can be examined in light of the very different post-MMORPG, online PbP world of RPGing we currently live in. Much of our discussion in the thread covered wide-ranging RPG topics, such as options bloat, character creation, Games Mastering, comparisons to MMO gaming and the impact of said gamers coming into the RPG environment, and much more.

I have found this to be an interesting read: much of it can be examined in light of the very different post-MMORPG, online PbP world of RPGing we currently live in. Much of our discussion in the thread covered wide-ranging RPG topics, such as options bloat, character creation, Games Mastering, comparisons to MMO gaming and the impact of said gamers coming into the RPG environment, and much more.

If you played Dungeons and Dragons before 3rd Edition, I think you should really give this book a read. You’ll find much to think about. And for you relative newcomers, you can get a look into a very different mindset. Either way, it’s the guy who co-created the game talking about how he thought you could become an expert at it.

And swing on over to the Paizo thread: there has been some excellent discussion (mostly from people other than myself…). I think your experience of the book will be enhanced by the thread commentary.

I’m breaking this down into a three-part series because it’s LONG. We’d be waaay over 10,000 words. And this approach lets me dive in a little deeper.

Let’s start looking at the Seventeen Steps of Role Playing Mastery per The Master:

1. Study the rules of your chosen role-playing game

Being intimately familiar with the rules structure is essential to understanding what you are doing, and understanding is the foundation of mastery.

He makes the point that simply memorizing a bunch of passages is not sufficient. Memorizing does not mean understanding (I like that phrase). It is not enough to know what is in the rules, but how the components all work together with each other. He discusses the problems faced by the rules writers, such as taking the make believe of dragons and spaceships and making them seem real. Quantification and mechanics must translate into an experience that brings to life the game environment.

As a player, whether the rules are inadequate or overwhelming, you must understand both the rules and the spirit of the game (Step #3). It is this accepted combination that leads to such exasperation with rules lawyers who focus solely on Step 1 and have no use for Step 3.

An adept GM can help overcome player shortcomings in the area of rules knowledge. But if the player consistently makes mistakes with movement or feats during combat rounds, the gameplay will be impacted negatively. Likewise, forgetting that a paladin has smite evil available can be the difference between success and failure. Two players understanding the rules for flanking is going to be much more effective than if only one does. Hard to flank by yourself!

2. Learn the goal(s) of the game

In other words, understand what the role of the PCs is in the game environment- the responsibilities and obligations of the player characters around whom the game world revolves. This is not the same as knowing what your individual role as a PC is; that is covered in step 9.

Gygax moves under the umbrella of the Player Character (PC) for several steps. Again using AD&D, he contrasts the styles of play and problem solving of fighters (brawn), magic users (brains) and thief (stealth). Playing different character classes (or types) gives you different perspectives on how to tackle problems and succeed in the game. In essence, he is saying that you can look at what types of character (classes) are available and how they are structured/function. From this, you can learn about the goals of the campaign world and the game itself.

He roams rather broadly on this point and doesn’t talk too much specifically about the game goals. But the concept is that you can explore the RPG system through playing different types of characters. Playing a ranger will certainly provide you a different experience and require a different approach to problem solving than playing a sorcerer. And a lawful good paladin will function differently than a neutral druid. He also contrasts the class (profession) system of character creation from the skill system. The way the character is built and functions gives an understanding of what the player can expect in the RPG. While I get what he was saying, I found this Step (as he explained it) to be rather muddy and easier to understand in its Step 9 form.

Now, the parameters within a specific campaign can certainly be affected by the character constraints and the goal. Solving a mystery (like TSR’s The Assassin’s Knot) will rely upon a different skill set and likely party composition than a slugfest dungeon crawl (like Necromancer Games’ Rappan Athuk Reloaded). But that is a micro look at what Gygax is saying, and he was really making his point a macro level.

3. Discover the spirit of the game, and make it your credo in play

The concept of “spirit” is defined in the foregoing text. Although the goal of a game may be contained within its spirit, the spirit of the game usually goes deeper. Perceive it, understand it, and have your PC live by it when you engage in play.

The Spirit isn’t something that you can easily tag with a phrase or a sentence. Gygax says that what lies between the lines (rules) is the Spirit of the Game. He elaborates:

To identify the spirit of the game, you must know what the game rules say, be able to absorb this information, and then interpret what the rules imply or state about the spirit that underlies them.

The Spirit pervades the stats, the mechanics and the descriptions of the rules. The Spirit of the Game gives the RPG a sense of tone, or flavor. Playing a board game like 221B Baker Street is a very different experience from one such as Wrath of Ashardalon. The Spirit varies greatly. Likewise with Pathfinder and Call of Cthulhu.

I like Gygax’s assertion that a player who masters the rules and just uses them to play the game without getting into the Spirit is simply going through the motions. He might become an expert in the game, but I would compare it to a dry, dusty experience.

If anybody could define the spirit of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (AD&D), it is certainly Gary Gygax. And here it is:

I shall attempt to characterize the spirit of the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons game. This is a fantasy RPG predicated on the assumption that the human race, by and large, is made up of good people. Humans, with the help of their demi-human allies (dwarfs, elves, gnomes, etc.), are and should remain the predominant force in the world. They have achieved and continue to hold on to this status, despite the ever-present threat of evil, mainly because of the dedication, honor, and unselfishness of the most heroic humans and demi-humans-the characters whose roles are taken by the players of the game.

I shall attempt to characterize the spirit of the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons game. This is a fantasy RPG predicated on the assumption that the human race, by and large, is made up of good people. Humans, with the help of their demi-human allies (dwarfs, elves, gnomes, etc.), are and should remain the predominant force in the world. They have achieved and continue to hold on to this status, despite the ever-present threat of evil, mainly because of the dedication, honor, and unselfishness of the most heroic humans and demi-humans-the characters whose roles are taken by the players of the game.

Although players can take the roles of “bad guys” if they so choose, and if the game master allows it, evil exists in the game primarily as an obstacle for player characters to overcome. If they succeed in doing this, as time goes on, player characters become more experienced and more powerful – which enables them to contest successfully against increasingly stronger evil adversaries. Each character, by virtue of his or her chosen profession, has strengths and weaknesses distinctly different from those possessed by other types of characters.

No single character has all the skills and resources needed to guarantee success in all endeavors; favorable results can usually only be achieved through group effort. No single player character wins, in the sense that he or she defeats all other player characters; the goal of the forces of good can only be attained through cooperation, so that victory is a group achievement rather than an individual one.

You can make of that what you will. I found two points that caught my interest. The first is that AD&D, as conceived (and created…) by Gygax was human-driven. As a Pathfinder Play by Poster, I certainly didn’t find that to be the norm anymore. I believe that humans were in the minority of two of my three PbP parties. And I played a dwarf, a half-elf and a human, respectively. Humans may rule Golarion, but demi-humans seem to be the prevalent choice of players.

Also, playing evil characters is more acceptable now. Many, if not most, PbP recruitments I see, still specify no evil characters (which certainly facilitates the ‘group working together concept’ of RPGs and mentioned in the last sentence of the previous quote). But playing an evil character is not as rare as it was 20-plus years ago. Fire Mountain Games was publishing Way of the Wicked, an adventure path for evil characters that was being used in at least one PbP at Paizo.com

But in looking at the big picture, you should understand the Spirit behind your specific game and incorporate it into your play. If you don’t do so, you’ll be experiencing less than the game was intended to provide.

I was a world class Ultimate (Frisbee) player. And the underlying premise, printed at the beginning of the rule book, is the concept of the Spirit of the Game. In essence, it is that it is NEVER acceptable to intentionally break the rules. In most competitive sports, the idea is that if you cheat (hold a pass rusher, goaltend, handball in soccer, whatever), there is a penalty if you get caught. You pay the price and move on.

In Ultimate, it’s simply WRONG to do something like that. You don’t do it and accept the price. You don’t do it, period. That’s why the sport does not have on field referees, even in world championship games. I played at world and national championships. I can tell you that a player who accepts Spirit of the Game and a player who does not have VERY different approaches to the sport. And they play the game very differently.

That’s just an out-of-context example of how understanding and accepting the Spirit which Gary Gygax talks about can impact a game.

One of the regular commenters in the Paizo thread took exception to the ‘No single character wins…’ paragraph just above:

This makes it sound like it should be the GM’s job to kill the PCs because that is “victory” for the campaign world. It also has the negative effect of putting the idea in the minds of players that being the “last man standing” is perhaps a good thing…

I replied:

I see what you’re saying on winning and victory. But I think there are two different aspects here.

Gygax is talking about the character. And the goal of the characters is to achieve whatever the quest is, which, presumably, involves overcoming obstacles and vanquishing the villain/guardian/etc whatever the specifics are. There are degrees of victory, but for your dwarf fighter or whatever, winning doesn’t mean that you, “Joe,” had fun.

I agree that if you had fun, even though your character died, you won. But you are talking about the player. Now, I think that is the most important part: if I’m not having fun, I’ll find something else to do. But I can have fun even if my character is not doing well.

As GM, I think the measure of ‘winning’ is whether or not the session went well and if the players had fun. This is a recreational activity, after all. I think the GM only has a relationship with the players, not the characters (that’s a statement I need to evaluate a bit further, I think). The characters the GM runs have a win and lose relationship with the player characters. The one laying dead with a sword through the neck is likely the loser!

But the GM coordinates the game play. He doesn’t necessarily win with a total party kill (though the GM characters do). He wins if the majority are pleased with the session. Of course, different things make different people happy. But as GM, you get a sense if it was a good game or not.

So, I think you have to limit Gygax’s comments in this post to the player character side of things.

Before heading onto Step #4, there was a short discussion on Rules Bloat. Well, I thought it was interesting. Maybe I’ll work that in later.

4. Know the genre in which the game is set, and study it often

Know the genre in which the game is set, and study it often. If your PC is to act as though the game world is his or her native environment, then you as a player must feel comfortable and at home in the genre of the game.

You cannot have a meaningful experience in a fantasy RPG without being familiar with the genre of fantasy as described in myth, legend, and literature. Likewise, background knowledge in science fiction, modern-day espionage, or the exploits of comic book heroes is vital if your game is set in one of those genres.

Gygax devotes an entire chapter (Searching and Researching) to this concept. He goes into detail on the different types of games, including fantasy, science fiction, time travel, detective/espionage, historical, etc. As I’ve mentioned before, he takes the book’s subject matter very seriously. He approaches selecting (or switching between) an RPG with the same gravitas that I use for buying a refrigerator or a lawn mower (can you tell I’m a home owner?). You really have to read this chapter to fully appreciate the work Gygax says is required in this area to become a Role Playing Master.

He makes an observation that points out how different the environment is today:

First, consumer demand changes as players tire of one subject and decide to shift to another. This is a meaningful shift whenever it occurs because most subjects dealt with in RPGs have very small audiences (a few thousand each)…

While most systems have relatively few numbers of players, when you add in PC/console RPGers, many millions of folks are playing RPGs now. Also, in the ‘old days,’ you didn’t simply fire up the PC and find everything you needed to know about any obscure RPG in a matter of minutes:

Probably the best way of finding out the available games is to contact game publishers for their catalogs, send away for catalogs offered by the big mail-order firms in hobby gaming, and go to a game store or “hard core” hobby shop and check things out with the people there. You should know the extent of what is offered. It is part of being involved in the hobby.

He also includes appendices of national conventions, associations and trade magazines to help players find out supplemental information. Many of us were introduced to RPGing through ‘someone’ we knew (that had the books). It’s a whole other world out there today. I’m not making fun of Gygax, but what he wrote below just isn’t how people think about RPGing today due to changes in technology and available information:

One would not claim to be an expert traveler, for instance, on the basis of having read many books on the subject and always having watched “National Geographic Explorer” on television. These activities may be evidence of a great interest in travel, but they are not themselves sufficient to warrant a claim of expertise in the field. When the enthusiast’s library is expanded and cultural, social, and ecological material is added to his background, a truly serious interest can be acknowledged. The interest can be even further explored and indulged through the viewing of travelogues and the collections of maps, photographs, and souvenir materials.

However, without the firsthand experience of actual travel by airplane, ship, railway, boat, auto, and all other means, the individual professing to be an expert traveler would be perpetuating a pretense. Imposture might be fun to read about, but it is hardly useful to the role game enthusiast outside actual play.

I’m pretty well read, but I’ve never tapped these books for my RPGing:

I recommend the reading of works such as A History of the Art of War in the Middle Ages, Town Government in the Sixteenth Century, The Domesday Book, The Welsh Wars of Edward II, and Numbers in History. Armor, weapons, fortification, siege craft, costume, agriculture, politics, heraldry, and warfare are the meat and drink of a serious participant in a game such as Dungeons & Dragons.

Want to play the Middle Earth RPG, The One Ring: Adventures Over the Edge of the Wild? You’ve got some work to do first.

For example, one company has produced a role-playing game based on the writings of J. R. R. Tolkien, specifically his books and stories set in the fantastic land of Middle Earth. The primary source material for the game master is the game itself. Beyond that, a game master who aspires to an intimate knowledge of this milieu should read the author’s works and keep them on hand for reference.

He should also learn about Tolkien by reading biographical or autobiographical information, to determine which literature, myths, and legends influenced the author’s creation of his fantasy world, and then peruse Tolkien’s source material. Likewise, the game master should examine previously published role-playing games and compare them with the game in question to ascertain which things influenced the designer and how the designer interpreted and presented these concepts in his own game. This need not be the end of the information-gathering process, for as noted, the quest can go on indefinitely, but this much work ought to give any student a solid and sizable background.

The chapter ends with a rather detailed ‘Outline of Study for Mastery.’ I can’t really convey the depth of commitment Gygax references in this chapter of his book. But I can assure you that you can’t just read a couple sourcebooks, maybe a fantasy/sci fi novel or two and be ready to be Mastery-level familiar with the game world of your choice. The level of effort required for a Masters Thesis would be more in the neighborhood.

5. Remember that the real you and your game persona are different.

An obvious fact, restated here for emphasis. The you of the game milieu is entirely different from the YOU of the world you actually live in, even if your PC happens to possess many of the traits present in your own personality and behavior patterns. And, just as obviously, the same goes for all the other players and PCs in the group.

DISCLAIMER: Just about every RPGer I know thinks the “RPGs can cause bad behavior” theory is 100% bunk. I’m not quite one of them. Read on..

I still remember the disbelief on Tom Hanks’ face when he realized his character had died in Mazes and Monsters (I think he jumped in a pit expecting treasure and got spikes instead). If you don’t know what happened after that, go rent a copy (not that it’s a great film). But in the seventies and into the eighties, there was a big to-do about Dungeons and Dragons having harmful psychological effects on kids and causing them to do violent things: to others and themselves. Mothers Against Dungeons and Dragons was perhaps the most visible entity of that movement.

Gygax was obviously sensitive to the issue and discusses it a bit in the book. Among the things he says:

Certainly, those who are or aspire to be role-playing masters do not have violent or aggressive personalities because of their participation in role-playing games. They understand that the conflict and violence in such games are only simulations, not meant to be translated into real-life experiences or used as an excuse for such behavior.

A master player or game master does not allow – in fact, never gives a conscious thought to allowing – actions taken in the context of the game to dictate or affect his or her activities in the real-world environment. A master knows the difference between role-playing, role assumption, and real life and never mixes one of these with another.

I am a Christian. I read the Bible and do a devotional every morning. I also listen to AC/DC, watch Justified, and play Pathfinder. My belief does affect what adventures I choose to play and how I play. But I recognize it is a game and not real. When my dual-wielding ranger in Age of Conan slices and dices a Pict barbarian, I don’t think, ‘It would be cool to chop up John in Purchasing like that.’ Though John could use a punch in the nose…

However, I do think that if you spend time in a fantasy world where you are shooting, chopping, killing and otherwise causing mayhem, that can affect your real world persona. It’s not the cause of what you may do, but it may contribute to your personality. If you’re not already rooted or well adjusted, RPGing can further knock you off balance. Just as other influences can. So, I do think there’s something to the issue.

But there’s not a cause and effect going on. I do agree that another point raised by Gygax is worth evaluating. He says that engaging in vicarious aggressive behavior is an outlet for such tendencies in humankind. It can be a substitute for some; just as it can be an influence for others.

If you replace the word ‘master’ with ‘player’ in the last sentence of Gygax’s quote above, I think it is exactly how things should be: A player knows the difference between role-playing, role assumption, and real life and never mixes one of these with another.

Whether or not you believe that RPGing can contribute to violent behavior, his point, that you absolutely should realize that you are not your character is a pretty basic one for role playing.

He added:

Two reports mentioned to me indicate that in the group of RPG hobbyists, the incidence of such behavior is fifty to two hundred times smaller than is typical of the populace at large.

No reference, no footnote, nothing. Just that mention. I found that rather amusing. Not exactly backed up enough that I’d use it in an argument.

Man, this got some people involved and worked up. Getting RPGers to acknowledge that it CAN be a bad influence is like trying to get Democrats and Republicans to converse in current times.

Reading ahead for the next couple of entries, this particular topic is the last of the steps that Gygax really goes in depth on. In discussing alignments, he again touches on the difference between real (player) life and character life:

It is neither wrong nor condemnable to act the part of a character who by the social and cultural standards of our society is bad, evil, or wrong. When all is said and done, games are not reality or actual life. It makes as much sense to vilify an actor for playing the role of a villain as it does to say that a participant in a game who has a PC whose moral standards cannot be called good is engaging in some form of wrongdoing.

Master role-playing gamers easily separate the difference between play and reality. In fact, even novices can do so without much difficulty.

As far as what I’ll just call “influence” regarding this topic, a Christian who reads the Bible and tries to live his life based on what it says, is going to have a different viewpoint than someone who doesn’t. I don’t bludgeon people with my faith like a morningstar, so I won’t go on about it here. That’s not what this thread is about.

Bear in mind I’ve said throughout it “can” be an influence, not that it definitely is. As I’ve said, some RPGers say it’s 100% rubbish, and I don’t take that position.

We’re in at almost 5,000 words, so I think the first Five Steps are enough. Next week will be Six through Twelve. Then a final post. Hopefully you enjoyed this. The comments and discussion over on the Paizo thread. If you’re into this stuff, these two Gygax books are absolutely for you. I think they’re dry reading, but obviously, I’ve still learned a lot from them.

Here’s PART TWO if you wanna continue on

Here’s PART THREE

And, some other RPG-related posts I’ve done here at Black Gate!

RPGing is Story Telling

Swords & Wizardry vs. Pathfinder

RIP Lenard Lakofka – Lord of the Lendore Isles

The Lost Lands for Pathfinder

The Northlands Saga – Complete

The Warlords of the Accordlands

Judges Guild Premium Editions

Gary Gygax’s Role Playing Mastery

Runebound

Runebound – The Sands of Al-Kalim

Runebound – The Mists of Zangara

Necromancer Games (Part One of two)

Frog God Games (Part Two of two)

Dungeons and Dragons Adventure Game System

D&D Adventure Game System – Temple of Elemental Evil

Dungeon! Board Game

Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective

221B Baker Street: The Master Detective Game

Steve Russell of Rite Publishing – RIP

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’).

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE Definitive guide to Conan. He also organized 2023’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, and XXXIII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

I wonder if Mr. Gygax ever noticed how Rule 4 and Rule 5 butt heads, in that Rule 4’s explanation says you cannot play a convincing expert traveler (character) unless you (player) have some real-life traveling experience. But Rule 5 cautions that “character” is not “player”. So “player” informs “character” but not vice-versa. Which is not quite my experience, I confess, as “character” can sometimes surprise “player” with a decision or response that is outside “player”‘s mental realm.

And I would agree that the “Satanic panic” of the 1980s (including Rona Jaffe’s Mazes and Monsters) was way overblown by groups like B.A.D.D (Bothered About D&D). But roleplaying is a powerful psychological tool and the emotions and feelings that it can engender are not without effect. And identification of “character” persona with player is quite possible, if not always desirable. It does hurt to lose a favorite character. Handle with (some) care!

Reading through the whole book, Gygax takes pains here and there to make sure of the player/character distinction. And it certainly makes sense to look at it in light of the whole ‘Satanic panic’ lens.

But man, does he strongly endorse reading anything remotely related to D&D or the campaign/scenario (I exaggerate, but not as much as you might think). And also, the developing of expertise through real-life. Which can be distinct from taking on your character’s persona.

I am reading some Harold Lamb, because he was a huge influence on Robert E. Howard (my second-favorite writer). Bu the idea of finding out what authors a module writer liked, and reading them, for insights into his

– I don’t know, module writing style? That’s a level way beyond, for me!

[…] (Black Gate): In 1987, Gary Gygax put out a book entitled Role-Playing Mastery, which gave guidelines on how to […]

[…] Black Gate’s Bob Byrne writes up Gary Gygax’s 17 Steps to Role-Playing Mastery (Steps 1 to 5). […]