Southern Horror: Pigeons from Hell by Robert E Howard

“Voodoo!” he muttered. “I’d forgotten about that—I never could think of black magic in connection with the South. To me witchcraft was always associated with old crooked streets in waterfront towns, overhung by gabled roofs that were old when they were hanging witches in Salem; dark musty alleys where black cats and other things might steal at night. Witchcraft always meant the old towns of New England, to me—but all this is more terrible than any New England legend—these somber pines, old deserted houses, lost plantations, mysterious black people, old tales of madness and horror—God, what frightful, ancient terrors there are on this continent fools call ‘young’!”

This exclamation by Griswell, the protagonist of Robert E Howard’s racially fueled horror tale set among the piney woods of the Louisiana-Arkansas border region, always struck me as a bit of a “take that!” to the old gentleman of Providence, HP Lovecraft. I think Howard was on to something as “Pigeons from Hell,” published posthumously in 1938 is a riveting tale of well-earned revenge, voodoo, and the walking dead. Two young travelers from New England decide to spend the night in an abandoned plantation mansion. The balustrade is covered by a flock of pigeons. Its oak door sags on broken hinges, and the interior is dark and dusty. After they fall asleep, they are ensnared by events set in motion many years ago.

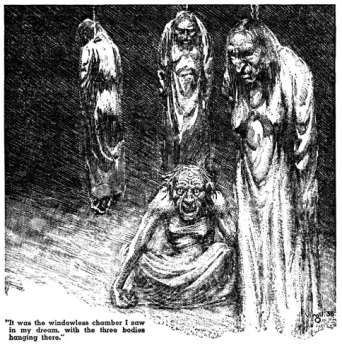

“Pigeons” opens with Griswell (no first name), waking up from a troubled sleep on the floor of a dilapidated plantation mansion. He had dreamt of a “vague, shadowy chamber” wherein “three silent shapes hung suspended in a row, and their stillness and their outlines woke chill horror in his soul.” In the corner crouched a “Presence of fear and lunacy.” As his eyes open, he spies something crouching at the top of a flight of stairs.

It quickly disappears, and a strange whistling, both “shrill and melodious” commences. Griswell finds himself frozen in place, unable to move or speak more loudly than a whisper. At the same time, his friend, John Branner, rises and mindlessly walks up the stairs toward the place where the crouching figure had lurked before disappearing into the darkness of the second floor.

The whistling dies out but is replaced by a sudden, awful scream. Freed from his strange constraint, Griswell rises up and sees Branner coming down the stairs, a bloody hatchet in his hand. What he sees next is even worse.

Yes! The figure had moved into the bar of moonlight now, and Griswell recognized it. Then he saw Branner’s face, and a shriek burst from Griswell’s lips. Branner’s face was bloodless, corpse-like; gouts of blood dripped darkly down it; his eyes were glassy and set, and blood oozed from the great gash which cleft the crown of his head!

Griswell flees the accursed house only to be chased through the pines by some canine shape with glowing green eyes. Only the sudden advent of Sheriff Buckner on horseback saves the terrified Northerner. From the sheriff, we learn the mansion was once the home of the Blassenvilles, a notorious French-English family from the Caribbean. He tells Griswell that the “Negroes said when a Blassenville died, the devil was always waitin’ for him out in the black pines.” Save one white tramp, only black people have ever seen the pigeons, and they believe them to be the souls of the Blassenville clan set free from Hell on certain evenings.

After the Civil War, only four sisters, supported by a handful of black sharecroppers, remained on the plantation. One day, an aunt, Celia arrived along with a mulatto maid. One by one, starting with Celia, the women disappeared until only the youngest, Elizabeth, remained. In 1890 she appeared in town raving that “something had chased her and nearly brained her with an ax”: something that looked “like a woman with a yellow face.” She left for California and since then, the house has been abandoned.

Despite his initial disbelief of Griswell’s story, the sheriff realizes something awful is at hand when he sees strange, bare footprints in the mansion and his flashlight dims unnaturally when attempts to explore the mansion’s second floor. Admitting that something uncanny underlies the night’s early events, he seeks out an old voodoo man, Jacob. He’s able to give the sheriff greater insight into the Blassenville’s evil and what might have happened to Griswell’s friend and the missing Blassenville women.

“The Blassenvilles,” he murmured, and his voice was mellow and rich, his speech not the patois of the piny woods darky. “They were proud people, sirs—proud and cruel. Some died in the war, some were killed in duels—the menfolks, sirs. Some died in the Manor—the old Manor—” His voice trailed off into unintelligible mumblings.

“What of the Manor?” asked Buckner patiently.

“Miss Celia was the proudest of them all,” the old man muttered. “The proudest and the cruelest. The black people hated her; Joan most of all. Joan had white blood in her, and she was proud, too. Miss Celia whipped her like a slave.”

One night, Joan came to Jacob for the secret of creating a zuvembie, the female counterpart to a zombie.

“A zuvembie is no longer human. It knows neither relatives nor friends. It is one with the people of the Black World. It commands the natural demons—owls, bats, snakes and werewolves, and can fetch darkness to blot out a little light. It can be slain by lead or steel, but unless it is slain thus, it lives for ever, and it eats no such food as humans eat. It dwells like a bat in a cave or an old house. Time means naught to the zuvembie; an hour, a day, a year, all is one. It cannot speak human words, nor think as a human thinks, but it can hypnotize the living by the sound of its voice, and when it slays a man, it can command his lifeless body until the flesh is cold. As long as the blood flows, the corpse is its slave. Its pleasure lies in the slaughter of human beings.”

“And why should one become a zuvembie?” asked Buckner softly.

“Hate,” whispered the old man. “Hate! Revenge!”

Armed with this information, Bruckner and Griswell return to the Blassenville mansion for a final confrontation with whatever evil lies waiting for them on the shadowed second floor.

“Pigeons from Hell” succeeds on two distinct levels, both of which reinforce my appreciation of Robert E Howard. They are intimately twined together, lending the story much greater depth than it might seem to have on first read. The first is the straightforward horror trappings and the second is the use of race as an animating force.

Howard’s horror tends to be a blunt force as opposed to the atmospherics of Lovecraft, as in “Pigeons” where the reader gets splashed with blood in the first few paragraphs. He doesn’t stint, though, at creating mood and setting, though. There’s a beauty to the pine woods surrounding the mansion filled with the scent of strange “plants and blossoms,” but under it lays the “reek of rot and decay.” With its creepy, derelict mansion, green-eyed wolf, and voodoo frights, this is a story that cries out to be filmed properly. Between these more standard horror elements, race is introduced.

Whatever Howard’s own opinion on race was, it is clear he understood the evil and degradation inherent in the slavery of the South. The South may figure in most white people’s imagination as “a sunny, lazy land…where life ran tranquilly to the rhythm of black folk singing in the cotton fields,” but the reality is dark and “fear-haunted.” Behind the horrible resolution are the crimes of Celia in particular, but also those of the entire Blassenville family itself.

Behind the white world of the Blassenvilles and the sheriff is a separate black world that Howard more than hints at. First, we learn that black people avoid the mansion. They are the only people who could see the pigeons, and when it was abandoned, they alone refrained from ransacking it. Next, we’re shown there’s the parallel world of voodoo and conjuration that exists only as rumor for whites, but as a real and frightening one for blacks. Venturing into this setting, still possessed of their simplistic vision of the South, ignorant of the weight of the sins that lie upon it, is what gets Griswell and Branner into trouble. Howard may not have set out to do anything more than tell a spooky tale, but the result is an indictment of the cruelties of at least one white family towards the people it held in bondage.

“Pigeons from Hell” was filmed for the Boris Karloff-hosted anthology series, Thriller (available for viewing, below), in 1961, starring Brandon De Wilde as Griswell. It’s passable, but it eliminates the racial aspect and trims away much of Jacob’s voodoo exposition. Someday, I hope it gets the film treatment it really deserves, Still, if you look between the lines it does hint at something I suspect Howard and the scriptwriter would have added if both had been a little braver. Instead of a mulatto maid, there was a servant named Eulalie who the sisters beat because she was their half-sister. I think both writers intended it to be clear Joan/Eulalie was both biracial and the blood-relation of the Blassenvilles.

NOTE:

“Pigeons” is a very good horror tale and one of Howard’s best. It’s also a product of its time and its author. The n-word is used liberally throughout the original text, though only by Sheriff Bruckner. Both the narration and Griswell only use Negro or black, clearly delineating the author and the protagonist from the coarser, native whites.

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Sunday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

Race is definitely an underpinning element in this story, one of Howard’s that has always stood out for me not least because of its intriguing title: pigeons are not normally birds I associate with anything more sinister than eating the crumbs after a family picnic or pooping on a statue. Speaking of adaptations, there’s an excellent graphic novel adapting Howard’s story by Scott Hampton, published by Eclipse in 1988 – it may be a bit hard to find these days but is well worth seeking.

Great, thoughtful article. My exposure to this story was through the “Thriller” episode when I picked up the wonderful Image DVD box set a number of years ago. It’s a handsome, competent piece of work but I always felt like something was missing and now I know what it was. I did also get a collection of Howard’s horror short fiction containing the story about the same time but have never gotten around to reading it. I’ll be pulling it off the bookshelf this weekend.

One of Howard’s best stories. Excellent post, Mr. Vredenburgh. Thank you.