Margaret Hamilton: Wicked Forever

The marketing blitz for the upcoming two-part film version of the 2003 stage version of Gregory Maguire’s 1995 novel Wicked (itself a “reimagining” of L. Frank Baum’s seminal 1900 novel, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz) has begun. Years ago, I succumbed to hype exhaustion and saw the musical; I found it mildly diverting, which hardly seemed adequate, considering the superlatives the enterprise was swathed in.

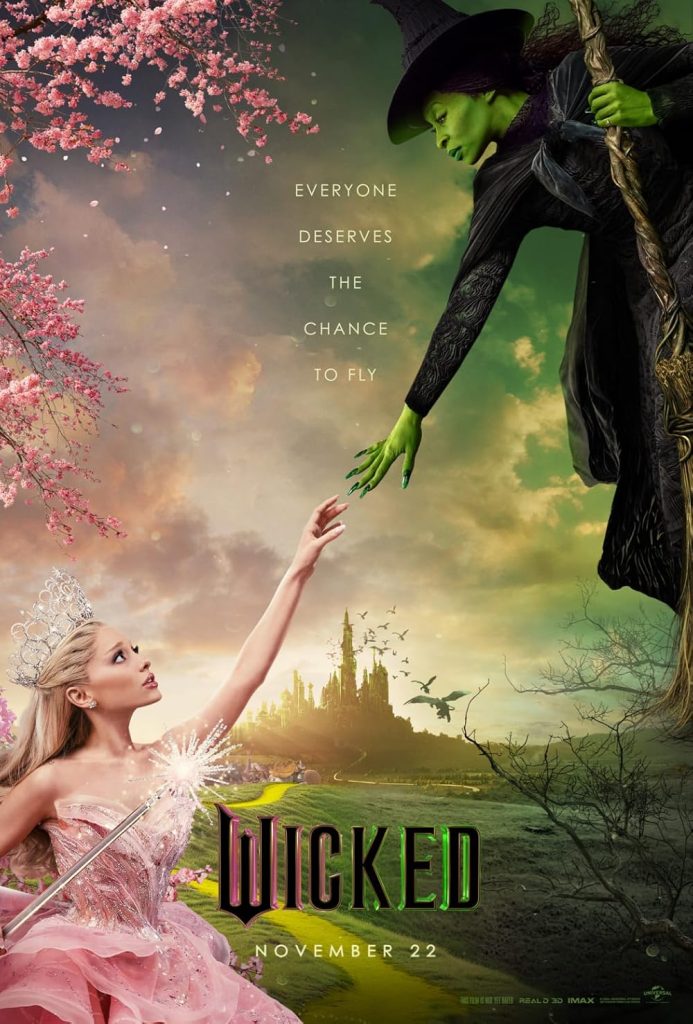

As for the movie, which stars Cynthia Erivo as Elphaba (Maguire’s name, not Baum’s, though it’s supposedly constructed out of his initials – LFB) and Ariana Grande as Glinda, so far all we have to judge it by is the trailer, and from those carefully culled three-and-a-half minutes it looks like all the stops have been pulled out in terms of lavish production values (though in a time when spectacle can be generated on a laptop, one wonders if that means anything anymore). As for the frantic media bludgeoning we’re about to experience, it’s hard to blame the producers for the incipient panic evident in such all-out campaigns; it’s not their fault that movies just don’t mean as much to people as they once did.

Nevertheless, I’m sure that when Wicked is released in November, it will be a smashing financial success and may even be an artistic one; certainly, a lot of talented people are giving it their all. Whatever the size of the film’s box office or cultural footprint, however, I suspect that not many people will still be watching it in 2109, eighty-five years from now — not coincidentally, the same gap separating 2024 from the 1939 that gave us one of the most enduring and beloved of all films, the MGM Wizard of Oz, a flawlessly-cast classic that starred Judy Garland, Ray Bolger, Jack Haley, Bert Lahr, and Frank Morgan.

No account of that great movie would be complete without mentioning another performer who was not as versatile as those others, and who didn’t have nearly as varied a career, but who is perhaps more iconic than any of them, and if, at the beginning of the twenty-second century, the dread name of the Wicked Witch of the West should be invoked, what is more likely to flash before people’s eyes — the elegantly attractive features of Cynthia Erivo, or the hatchet-faced visage of Margaret Brainard Hamilton?

Margaret Hamilton had a fifty-year career in movies, beginning with her first film appearance in 1933 and ending with a television movie in 1982, just three years before her death at the age of eighty-two. Throughout those years, she was a reliable and busy supporting player, specializing in nosy neighbors, censorious busybodies, meddling do-gooders, penny-pinching shopkeepers and sour, pickle-pussed crones of all descriptions; with her sharp, angular features and snappish, grating voice, it was hardly likely that she would be cast in any other roles. (When her agent told her that MGM wanted her for the Witch, she said, “The Witch?!” and he replied, “What else?”)

That kind of limitation wasn’t a problem in the golden age of studio-era Hollywood, though, which always had plenty of roles for performers of very specific looks and very narrow talents. Barry Fitzgerald spent an entire career as a professional (usually inebriated) Irishman; George Sanders played the same suave cad over and over for four decades; every time you saw C. Aubrey Smith you knew you were getting a blustering, stiff-upper-lip British colonel just back from the Punjab. Perhaps there is no better example of Hollywood’s endless need for such performers than Margaret Hamilton, who also demonstrates something else — that if actors got the right kind of archetypal role that exactly suited their talents, the movies had the magical power to make them immortal.

In The Wizard of Oz, Margaret Hamilton (who, it is imperative to say, was by all accounts a gentle, sweet-souled lady) got one of those roles. With a broomstick in her hand and a leering troupe of flying monkeys at her command, she’s the embodiment of unequivocal evil; to use L. Frank Baum’s word, she’s wicked, which, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, means that she is “bad in moral character, disposition, or conduct; inclined or addicted to willful wrongdoing; practicing or disposed to practice evil; morally depraved.” In the 1939 film, Hamilton is as wicked as wicked can be; she’s irredeemably, indelibly wicked. She’s wicked forever.

In stark contrast to the MGM masterpiece, however, one of the purposes of Maguire’s novel and the musical and movie that have sprung from it is to alter our perspective and unsettle our assumptions. When we see evil acts, we know it, but what do we really know about the history and motives of those who commit them? Does a “wicked” action necessarily make a “wicked” person? Doesn’t everyone have their reasons? And anyway, is the official story, where some are lauded as heroes while others are damned as villains, always the true one? Isn’t history usually just a lie constructed to serve the powerful?

These questions are certainly legitimate ones, though I do wonder how well it would go over if the revisionism that has been applied to Elphaba, the Wicked Witch of the West, was also extended to, let us say, Hermann Goering, Marshal of the Greater German Reich. (That’s probably not entirely fair, but if Macguire and his successors feel entitled to ask their questions, I feel entitled to ask mine.)

But arguments about the nature of evil and the reliability of accepted narratives aren’t the point here; Wicked’s Witch may well be truer to the way things actually are (in Kansas if not in Oz) than the Witch in The Wizard of Oz, but in the long run that doesn’t matter. In the battle for our dreams, a semi-tragic, complexly motivated Witch with an interesting backstory simply cannot compete with Hamilton’s rasping cackle of pure, unmitigated evil, cannot begin to replace the malicious, black-robed figure who gloatingly mocks Dorothy’s cries for Auntie Em and assures the terrified girl that when the sands in the hourglass run out, she will die. As any Munchkin can tell you, aesthetically, a sympathetic Wicked Witch doesn’t stand a chance against the vicious hag who hates cute little dogs.

The Wicked Witch of the West of The Wizard of Oz is not a nuanced character, but what she lacks in subtlety she more than makes up in mythic power. Margaret Hamilton, who never waltzed with Fred Astaire, was in the right place at the right time to stake her claim as one of the most towering figures in our collective imagination, our Queen of Nightmares.

She seemed to realize that she had been given a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, and her total commitment to the Witch is courageous and… well, almost supernatural; she never once winks at the audience, never once hints that she’s actually a nice person who doesn’t really mean it, and the result is a performance of extraordinary resonance. She sank her talons into the role with a ferocity that is as exhilarating as it is frightening and so became an ineradicable image of a timeless, primal fear that everyone knows, that everyone understands and responds to, and when good-looking actors who could sing and dance and play sigh-inducing love scenes are long forgotten, she will live on in the shadows of a million midnights.

Margaret Hamilton will be the Wicked Witch for as long as our culture lasts, and if, a millennium after it falls, archeologists should be poking around in its ruins and happen to unearth a torn and soiled photograph of her in The Wizard of Oz, a collective shudder will run through them as they gaze on that cruel, green, flint-eyed face; they will look at each other uneasily and say, in lowered voices, “I don’t know who this woman was, but whoever she was, she was wicked!”

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was A Book Worth Reading Every Year: Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White

I quite liked the musical, Wicked, and my wife adores it. (She also read the (much darker) Maguire novel and liked that too.) Part of my enjoyment was the music, to be sure. I think Cynthia Erivo can be a good Elphaba, though I’m skeptical about Ariana Grande as Glinda. And I don’t really think it justifies being a two parter.

I don’t have any major problems with the musical (though for me, nothing can replace South Pacific); as I implied in the piece, I just find it hard to respond naturally or positively to anything if it’s wildly overhyped. (Pretty much means I’m totally screwed, doesn’t it?)