A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Hammett & ‘The Girl with the Silver Eyes’ (My intro)

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

(Gat — Prohibition Era term for a gun. Shortened version of Gatling Gun)

Pulp Fest took place last week in Pittsburgh. It’s a really cool event, and the Hilton Doubletree is a nice site. Steeger Books rolls out its summer line at this event. And for the second year in a row, there was a new Continental Op collection, with a brand new intro by yours truly. This is my sixth intro for Steeger, and getting to write about Dashiell Hammett is a definite thrill. It’s about four times as long as my Fast One Intro. I could dig into Hammett for months. Check out my intro to that Volume Two, and then check out the book itself. Hammett is regarded as the Master, for good reason.

The Complete Black Mask Cases of the Continental Op, Volume One: Zigzags of Treachery, ended with “The House in Turk Street.” That was the tenth Op story, and as I wrote in the introduction to that volume:

‘For me, it’s in “The House in Turk Street” (which was adapted for the 2002 Samuel L. Jackson movie, No Good Deed) where we really see the classic Hammett for the first time. The characters, the pace, the tension, the plot elements: he was moving from learning, to improving, to the verge of mastering.’

Hammett had been honing his craft, and “The House on Turk Street” really saw things come together. While that was the first Hammett story to appear under Phil Cody’s editorship, it was surely accepted by George Sutton.

THE GIRL WITH THE SILVER EYES

Next up two months later in June of 1924 was “The Girl with the Silver Eyes.” It was a sequel to “The House in Turk Street,” and twice the length. Together, they are about as long as the first four Op stories combined. Hammett was moving towards the long form that would result in four serialized novels: at least three of which are regarded among his best works.

“The Girl with the Silver Eyes” appeared in the same issue as Carroll John Daly’s “The Red Peril.” Compare the two stories. Daly (who I talked about in volume one) was still writing the same one-dimensional character, with the same ultra-violent action. Hammett had continued to use his real-world Pinkerton experiences while honing his writing skills, and his work was notably improved from the first Op tale.

It is rightly considered one of his best stories. Burke Pangburn (client), Jeanne Delano (silver-eyed girl), and Porky Grout (criminal informant) are all well-drawn characters, with depth. Delano takes the femme fatale seen in “The House in Turk Street” a level further, and Hammett doesn’t just tell us that men cannot resist her – he shows it in dramatic fashion. In dealing with her, the Op faces his greatest emotional test so far.

I said in volume one: ‘Hammett used his experience as a Pinkerton to write more realistic detective fiction. As Raymond Chandler wrote of him: “He made some of it up; all writers do; but it had a basis in fact; it was made up out of real things.”’

Porky Grout is a snitch. Today’s cop shows would call him a CI (criminal informant). He’s a stool pigeon in Hammett’s slang. He’s been mentioned before, but we meet him for the first time and get the full view:

‘I don’t know a single thing that could be said in his favor. He was a coward. He was a liar. He was a thief, and a hophead. He was a traitor to his kind and, if not watched, to his employer…

Detecting is a hard business, and you use whatever tools come to hand. This Porky was an effective tool if handled right, which meant keeping your hand on his throat all the time and checking up every piece of information he brought in.’

It’s more practical advice from Hammett, via the Op. I find Porky, and how he interacts with the Op – and how that reflects another relationship – one of the most interesting aspects of this volume.

The CODY – HAMMETT WAR

An odd thing happened before “Women, Politics, and Murder,” saw print in September of 1924. I mentioned last volume that Harry North was George Sutton’s, and then Phil Cody’s, right-hand man. He was also ‘the bad guy’ with the writers. Cody rejected two of Hammett’s stories, with North sending a letter (and returning the stories) to Hammett. Cody was establishing his authority and took to passively-aggressively shaming Hammett. The August issue included Cody talking about rejecting these two stories, and all of Hammett’s response, under the heading Our Own Short Story Course. In the intro, Cody says:

“We recently were obliged to reject two of Mr. Hammett’s detective stories…But in our opinion, the stories were not up to the standard of Mr. Hammett’s own work – so they had to go back.”

Sarcasm can certainly be detected in Hammett’s response. Cody would publish him less frequently than Sutton did, and he was rejecting stories. This August feature did not evince a happy editor-writer relationship. Of one of the rejected stories, Hammett wrote:

“I don’t think I shall send “Women, Politics, and Murder” back to you – not in time for the July issue anyways. The trouble is that this sleuth of mine has degenerated into a meal-ticket. I liked him at first and used to enjoy putting him through his tricks; but recently I have fallen into the habit of bringing him out and running him around whenever the landlord, or the butcher, or the grocer, shows signs of nervousness.”

He says he could possibly patch it up to get by with the story, but doesn’t think it’s worth the trouble.

Cody said that Hammett’s letter could be a primary course in short story writing. I think he totally missed Hammett’s sarcasm. You tell me if this isn’t a bit of snark:

“I want to thank both you (North) and Mr. Cody for jolting me into wakefulness. There’s no telling how much good this will do me. And you me sure that whenever you get a story from me hereafter, – frequently, I hope, – it will be one that I enjoyed writing.”

The Cody/North – Hammett relationship was not a healthy one, as evidenced by this incident, and in less than two years, with Cody still as editor, Hammett would quit Black Mask. Interestingly enough, Cody and Hammett both were largely correct about the story. It’s not a particularly good one. And it’s clearly a regression from “The House in Turk Street,” and “The Girl With the Silver Eyes.”

WOMEN, POLITICS, AND MURDER

In “Women, Politics, and Murder,” a frantic Mrs. Gilmore has hired the Continental Detective Agency to discover who murdered her husband, Bernard. He had been involved in politics, and recently had an affair with a Carla Kenbrook. The widow suspects that the police may not want anything unseemly to come out, and aren’t investigating as hard as they should be.

In “Women, Politics, and Murder,” a frantic Mrs. Gilmore has hired the Continental Detective Agency to discover who murdered her husband, Bernard. He had been involved in politics, and recently had an affair with a Carla Kenbrook. The widow suspects that the police may not want anything unseemly to come out, and aren’t investigating as hard as they should be.

Bernard had had a shady reputation as a guy who had gone from construction grunt to business owner to politician. Scandals had surfaced, but none had stuck to him. Hammett shows what a master wordsmith he is by describing him as ‘a roughneck with a manicure.’ That, in only four sparse words, is absolutely perfect to give us our picture of the man.

As for Cara: ‘It wasn’t a beautiful face, although It should have been. Everything was there – perfect features; smooth, white skin; big, almost enormous, brown eyes, – but the eyes were dead-dull, and the face was empty of expression as a china door-knob, and what I said didn’t change it.’

This is one hard sister.

“Women, Politics, & Murder” all takes place in the space of one day. And, frankly, it’s not that great a story. The characters aren’t compelling, the crime isn’t that absorbing, and the denouement is rather weak. This is one of the least-read Op stories for me. I can understand why Cody wasn’t thrilled with it. I find the whole “Our Own Short Story Course” matter more interesting than the actual story itself.

But it’s still the Op. And watching him work is always interesting. He finds himself in a tight spot, working against lies, and against a powerful figure. Hammett gives the Op the upper hand, then paints him into a corner. I leave it to you to decide if the resolution was satisfactory.

Hammett’s lung problems worsened in 1924 and he was writing to pay the mounting bills. Cody didn’t want to saturate the magazine with his stories, and only printed him every other issue, at most. Hammett was extremely displeased that the editor was limiting his income. As was the case for most Pulp writers, Hammett was not making a great deal of money at a penny or two a word (Stephen King’s ‘Get rid of your adverbs’ advice did NOT apply to the Pulps!). And he wasn’t nearly as prolific as contemporaries Erle Stanley Gardner, and Raoul Whitfield. He needed the income from Black Mask. Tensions would continue to rise.

THE GOLDEN HORSESHOE

All but two of the Op stories appeared in Black Mask. The second appeared in True Detective, the same month in which Black Mask had “The Golden Horseshoe.” Two stories in a month meant twice as much income to the cash-strapped Hammett. And Cody wouldn’t print a new Op story until March – four months away.

Vance Richmond, the client in “Zigzags of Treachery” and “One Hour,” gets the Op another case. Reading the opening, it feels like he’s hiring the Op directly, not the Continental Detective Agency. But that could just be my take. And while I noticed it, frankly, it doesn’t matter, so let’s move on.

Norman Ashcraft was a clean-cut Britisher whose wife inherited a lot of money. She was rather possessive, and accused him of paying too much attention to another woman. He was already sensitive about their financial disparity and he packed up and left. She repented within a week, but he had fled England.

Eventually, they ended up exchanging letters while he was in San Francisco, telling her to quit searching for him, and to just leave him alone. Then he revealed that he was a drug addict; he wouldn’t return until he cleaned himself up. She sent him money regularly ‘to help.’ She packs up and moves to San Francisco: he says he’s getting better, and then relapsing, while she continues to pay him monthly, care of General Delivery. Finally, she wants some answers one way or another, and goes to Richmond, who hires the Op to find Ashcraft – under whatever name he is likely using. That’s the chapter one setup.

Eventually, they ended up exchanging letters while he was in San Francisco, telling her to quit searching for him, and to just leave him alone. Then he revealed that he was a drug addict; he wouldn’t return until he cleaned himself up. She sent him money regularly ‘to help.’ She packs up and moves to San Francisco: he says he’s getting better, and then relapsing, while she continues to pay him monthly, care of General Delivery. Finally, she wants some answers one way or another, and goes to Richmond, who hires the Op to find Ashcraft – under whatever name he is likely using. That’s the chapter one setup.

Once again, Hammett uses his Pinkerton knowledge – this time, regarding postal inspectors – and has the Op stake out General Delivery. And when someone who is not Ashcroft picks up the monthly letter, he bumps into the man to get a look at the address. It doesn’t go smoothly and he knocks the man down: its obvious what the Op is up to. Knowing Ashcroft will certainly be warned somebody is after him, Hammett pretends to have a gun and forces the letter carrier to the man’s apartment. Now pretending to be the law, he gets some info, then has him put on ice (turns out the man, Ryan, had an out-of-state warrant on him). And off to Tijuana and The Golden Horseshoe, goes the Op.

The Op finds Ashcroft (now going under the name Bohannon (we’ll stick with Ashcraft), gets drunk a lot, gathers some info, and returns to San Francisco…to find the client dead, along with two servants – all with their throats slit.

The Op makes things happen in this one. He doesn’t just follow clues and ferret out the villain. As he says:

“One way of finding what’s at the bottom of either a cup of coffee or a situation is to keep stirring it up until whatever is on the bottom comes to the surface. I had been playing that system thus far on this affair.”

He suspects who the killer is, then uses some stooges to spook him, causing him to run and hide. The Op confronts Ashcraft and his girlfriend and when the muscle-in-hiding shows up, the stirring is done – with bodies left on the floor and a car chase across the desert.

One weakness for me: the entire final chapter up to the very last part, is the villain revealing everything he did. He’s already been captured, so it’s not like the super villain telling all to the spy hanging over the shark tank with a candle burning the rope: but it’s a long confession and of course, leads to his downfall. I was kind of tired by the end of it, and the end of the story.

The Op has his own sense of justice at the end of the story, and the reader is left believing that the bad guy is absolutely getting his just desserts: but not for the reason we thought.

Just before things blow up, the Op voluntarily gives up his gun and tells the bad guy he wants to take him back to San Francisco in handcuffs, but he’s got plenty of time to do so. Can you imagine Race Williams offering up his gun so he can talk a guy into capture? Whenever that might work out? And the Op doesn’t kill anybody in this one, toning down the violence which had been escalating in his stories.

WHO KILLED BOB TEAL

“Who Killed Bob Teal” was less than half as long as “The Golden Horseshoe. It wasn’t even as long as “Women, Politics, and Murder.” What it was, was the other story rejected by Cody and North as revealed in Our Own Short Story Course. In his reply, Hammett had referred to it as “The Question’s One Answer.” THAT would have been a terrible title. True Detective magazine presented fictional stories as if they were real. So, the Pulp’s name was a bit of a stretch. The title page for “Who Killed Bob Teal?” identified it as ‘by Dashiell Hammett of the Continental Detective Agency.’ That isn’t exactly the truth now, is it?

Teal was a young operative at the Continental, having previously appeared in “Slippery Fingers” and “Zigzags of Treachery.” While he was described as “a youngster who will be a world-beater some day,” it’s safe to guess from the title that there would be no fourth appearance.

Teal was a young operative at the Continental, having previously appeared in “Slippery Fingers” and “Zigzags of Treachery.” While he was described as “a youngster who will be a world-beater some day,” it’s safe to guess from the title that there would be no fourth appearance.

This is another compressed story, which takes place in less than a day. It’s definitely far more like “Women, Politics, and Murder,” than it is the sprawling “The Golden Horseshoe.” The Op wears out some shoe leather in this one. In the intro to volume one, I talked about how Hammett had the Op doing the mundane tasks involved in solving a case. It’s not all guns blazing, as with Daly’s Race Williams. Here, he chases clues by talking to people until something breaks, and then he turns the tables on the unsuspecting bad guy.

Almost the last quarter of the story is a long monologue by the Op, explaining everything to the clueless cop. There are constraints in a short story, of course. But for me, the long-winded explanation at the end is always a flaw, unless it’s done in a way that keeps you engaged. I find that Rex Stout often avoids the pitfalls in the gatherings that Inspector Cramer calls Wolfe’s ‘charades’ at story end.

I had to stop and re-read parts as the Op droned on, explaining who did what and why. It’s simply a weak ending. But the story itself isn’t without merit. In fact, if you reflect on it when you’re finished, you’ll realize that Hammett drew on this in writing The Maltese Falcon. I don’t wanna give any spoilers, but when you stop and look for them, you will absolutely see the similarities. This isn’t a bad little story, but Hammett took elements of it and made it better, by ‘borrowing’ from it for his tour de force novel.

I like this story better than I do “Women, Politics, and Murder,” though I’m guessing neither makes anyone’s Top Ten list. Hammett sent it off to True Detective – likely with little or no revision – after telling Cody that he didn’t think it was worth the trouble of ‘patching up.’ And by submitting it to a different magazine, it strengthens my feeling that he was insincere is his response to Cody’s rejection in Our Short Story Course.

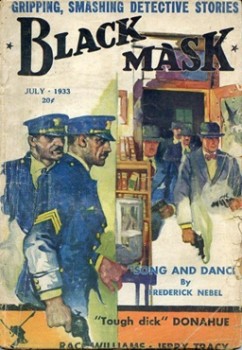

MIKE OR ALEC OR RUFUS

“Mike or Alec or Rufus” appeared in January of 1925, and it was even shorter than “Who Killed Bob Teal.” Hammett had reached his high point (so far) with “The House in Turk Street,” and “The Girl with the Silver Eyes.” It seems that a combination of his health issues, financial difficulties, and dislike of Cody, had retarded his progress. He was writing shorter, lower quality stories. I will still read ‘lesser stories by Hammett, Frederick Nebel, and Raoul Whitfield. But it can be obvious to me when the writer is ‘on his game,’ and when it’s just a story to get published. And Hammett not near his best is still a talented guy. But his ongoing growth was stalled, as his feelings towards Cody grew more negative.

I have to say, “Mike or Alec or Rufus” (briefly) has quite an attention-getting opener:

‘I don’t know if Joseph Coplin was tall or short. All of him I ever got a look at was his round head – naked scalp and wrinkled face, both of them the color and texture of Mila paper – propped op on white pillows in a big four-poster bed. The rest of him was buried under a thick pile of bedding.’

First time I was reading it, I thought the head was not attached to the body. Then I got to that final sentence, and realized it wasn’t a detached head on the pillow. But for a second, I thought this one was off to one crazy start.

First time I was reading it, I thought the head was not attached to the body. Then I got to that final sentence, and realized it wasn’t a detached head on the pillow. But for a second, I thought this one was off to one crazy start.

A robber forced his way into the Coplin apartment, stole some jewelry, shot Joseph in the leg, and locked him, his wife, daughter, and the maid, in a closet. The insurance company hired the Continental agency, and the Op was assigned to the case.

The story takes place in a couple of hours, and entirely within the Conlin’s apartment building. Bill Garren, a detective on the police’s Pawn Shop Detail, shows up and works hand-in-hand with the Op. This story feels like it could be turned into a play, with only a few rooms needed for the sets.

Garren shows up with an obvious (and obviously wrong) suspect, and is annoyed when he clearly strikes out. It’s the Op who just keep asking questions and trying to fit pieces together. He sets aside the puzzle pieces that don’t fit, and tries to join other ones together. No guns blazing and bad dialogue like, “He made his bed and I laid him out in it – full of holes.”

The robber couldn’t flee the building, but couldn’t be found in it, either. It’s as if Hammett wanted to tinker with the conventional locked-room mystery and turn it into a hardboiled locked-building mystery, with no gun play or violence. It’s an interesting idea, and I think he pretty much pulls it off.

The robber had inside knowledge, which made the Op suspect the family. Garren’s suspect was the son of a neighbor. It’s like the ensemble of an Agatha Christie country house murder. But the Op just keeps looking for information and discarding what doesn’t work.

This story contains another example of Hammett sharing his real-world experience, through the Op:

‘An identification of the sort the janitor was giving isn’t worth a damn one way or the other. Even positive and immediate identifications aren’t always the goods. A lot of people who don’t know any better – and some who do, or should – have given circumstantial evidence a bad name. It is misleading sometimes. But for genuine, undiluted, pre-war untrustworthiness, it can’t come within gunshot of human testimony.

Take any man you like – unless he is the one in a hundred thousand with a mind trained to keep things straight, – and not always even then – get him excited, show him something, give him a few hours to think it over and talk it over, and then ask him about it. It’s dollars to marks that you’ll heave a hard time finding any connection between what he saw and what he says he saw. Like this McBirney – another hour, and he be ready to gamble is life on Jack Wagner’s being the robber.’

That’s Hammett praising the value of circumstantial evidence, over eye-witness testimony. Even in this, his shortest story (about the same length as “Bodies Piled Up”), Hammett can still provide insights from his Pinkerton days, lending an authenticity and sense of grounding to his stories.

The finale is stronger than in the prior story. There is some conversation – it’s not a monologue. And the villain is revealed over the course of the speech. It’s not an after-the-fact explanation. This is a much more satisfactory way to close out the story. Including a final paragraph in which he reveals where the stolen jewels were found.

This is a slight story, but a pleasant read. More of a “Hmm. I wonder…” type of story, than something you get absorbed in. And there’s zero action. It really does feel like more of a small play.

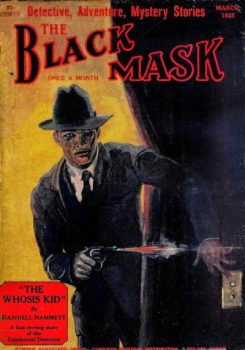

THE WHOSIS KID

The final story in this volume is “The Whosis Kid,” and it’s longer than the previous two stories combined. Hammett was back on an every-other-month schedule with Cody, and it appeared in the March, 1925 issue.

After a couple relatively ‘minor’ efforts (some might even say ‘lackluster’), Hammett returned to the longer, action-packed form that marked his best work. It’s definitely the best story in this volume. And, as with “Who Killed Bob Teal,” the reader can find ideas and elements which Hammett would draw on for The Maltese Falcon. Raymond Chandler referred to ‘cannibalizing’ his short stories, for his novels. Hammett certainly didn’t go to that extreme, but you can see that he definitely remembered some things from a few of his short stories when he wrote The Maltese Falcon.

The story starts with the Op having a flashback to almost eight years prior, when he worked out of the Boston office. We get about as much of his past life as we ever do, in this opening. The Op happens to run into Lew Maher (who may be another Continental operative). We learn that a week or two later, the Op joined the Army until the war ended, after which he went to the agency’s Chicago office. A few years later, he transferred to San Francisco, which is where he was when the stories started.

Maher points out a passing gunman, the Whosis Kid. Hammett was so good at adding little touches to his stories. Things that aren’t vital, but which add depth. Maher says:

‘“I’m going to clamp (catch) him some day, though – and that’s a promise.”

Lew never kept his promise. A prowler killed him in an Audobon Road residence a month later.’

Something about this makes me stop and take a breath. Lew Maher existed solely to point out The Whosis Kid to the Op, eight years in the past. That’s it: Only reason we ever hear of him. But somehow, with that little comment about Maher being killed in the line of duty a month later, he has a memorable presence in the series. He’s never mentioned again, but when we come across this story again, or hear of The Whosis kid, we remember that guy who pointed him out to the Op, and how he died not long after.

It’s not a big thing. It’s not even important. But it’s Hammett reminding us that, Damn, he’s good.

Boxing was a HUGE sport on the West Coast in the thirties and forties. Going to the fights was a regular thing. The Op had been working hard and goes to the fights at Dreamland Rink, which was a San Francisco institution for seventy years. He had noticed, back in Boston, that The Whosis Kid had irregularly-shaped ears. And he notices those ears again, a few rows ahead of him, as he watches the action in the ring. It tickles a memory, but it’s not until he sees the Kid’s face that he makes the identification.

Boxing was a HUGE sport on the West Coast in the thirties and forties. Going to the fights was a regular thing. The Op had been working hard and goes to the fights at Dreamland Rink, which was a San Francisco institution for seventy years. He had noticed, back in Boston, that The Whosis Kid had irregularly-shaped ears. And he notices those ears again, a few rows ahead of him, as he watches the action in the ring. It tickles a memory, but it’s not until he sees the Kid’s face that he makes the identification.

He figures, ‘once a criminal, always a criminal,’ and decides to follow him. He tells the office boss (The Old Man) about the Kid, and learns that the Kid is suspected in a jewelry robbery back East, and the Boston branch authorizes San Francisco (and the Op) to check him out.

The Op is tailing the Kid when somebody shoots at the gunman during a drive-by. The Op gets busy: following the car; then switching to a man who gets out of the car; connecting with a house dick and monitoring calls at the switchboard; seeing an intentional car wreck and attempted kidnapping; and ending up with a femme fatale, with a gun, in the car with him as they flee the scene.

The most recent stories had been rather sedate. This was full-blown Op action. There’s a cast of characters and more mistrust than a bootlegger at a Prohibition meeting. There is no honor among thieves, and the Op finds himself in an apartment with all the players, some jewels missing, and a lot of guns. If, like me, your favorite hardboiled novel – and movie – is The Maltese Falcon, you might be seeing a few similarities at this point.

Maurious is a weaker Caspar Gutman. Imagine The Whosis Kid as Wilmer-tough, but a third party – not just a gunman. Ines is the classic femme fatale playing her own game. She even picked up a sort-of Floyd Thursby along the way, though it’s a different relationship. There’s a guy nicknamed Big Chin who serves as Maurious’ heavy, in lieu of Gutman’s Wilmer.

Unlike Race Williams, the Op uses his brains, not guns, to manipulate the situation. But he’s a man of action who isn’t afraid to shoot, and when things blow up, lead and blood follow. This one doesn’t get resolved with the delivery of a wrapped-up statue.

The action ends in the next-to-last chapter, and Hammett gives us an O. Henry twist which I find entirely satisfying. It’s perfect. There’s a short final bit with the Op narrating the details of the whole thing, but it’s not too long, and it’s not too confusing. As far as these ‘Op Wrap-Ups’ go, I thought it was one of the better ones. And it followed crazy action, which makes it more palatable. Kind of like a five-minute cool down after a half-hour jog.

SO….

This book starts and finishes with top-drawer Hammett: “The Girl with the Silver Eyes,” and “The Whosis Kid.” Due, I think in large part to his unhappiness with Cody; and also the health and financial difficulties in his real life, the stuff in-between could have been better. It’s still Hammett, and it’s absolutely still worth reading. But the momentum that had built through “The Girl with the Silver Eyes,” definitely decreases. However, “The Whosis Kid” is a welcome return to form. And as we know, the terrific serial novels were soon to come.

Frederick Nebel, who Joseph ‘Cap’ Shaw would tag to replace Hammett when the latter quit Black Mask for good, was still a year away from his first story in the magazine. Erle Stanley Gardner was in his third year at Black Mask, but the first Ed Jenkins story had only appeared two months before, in January. ‘Average’ Hammett was still the best hardboiled stuff being printed in the magazine: unless you were partial to Carroll John Daly’s style.

Hammett wasn’t always at his best, but he was still always just about the best. He continued to write with a lean prose style, and incorporating his experiences as a Pinkerton brought a realism not found elsewhere. Pulpsters were cranking out stories to make a living on miserly wages. But Hammett was doing it with a professional style in a field he was continuing to shape.

New Op stories would appear in Black Mask in May, September, November, and December. So, it was Cody’s every-other-month schedule, until a December ‘bonus.’ Then, there wouldn’t be one until March of 1926, and he would quit Black Mask.

Hammett had now written fifteen Op stories for Black Mask (with a sixteenth appearing in True Detective). In merely a year and-a-half, he had co-created (with Daly) a new type of mystery story, evolved both, the form, and as a writer, and was redefining the mystery story in America. The novels were still ahead, but Hammett’s impact in only eighteen months was colossal.

The Cody-Hammett relationship would deteriorate, and as you’ll read in the volume three intro, Hammett would quit Black Mask, and the Pulps altogether. It would take Joseph ‘Cap’ Shaw’s editorship to lure Hammett back to the Mask.

Other Steeger Books Intros I’ve Written:

Hugh B. Cave’s Peter Kane

Hugh B. Cave’s Peter Kane

Norbert Davis in Black Mask – Volume 1

Norbert Davis’ Max Latin

Dashiell Hammett – ZigZags of Treachery

T.T. Flynn’s Mike & Trixie (The ‘Lost Intro’)

John Lawrence’s Cass Blue

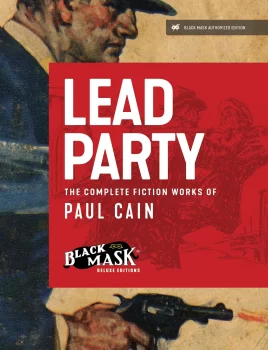

Paul Cain’s Fast One

Prior Posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2024 Series (8)

Will Murray on Dashiell Hammett’s Elusive Glass Key

Ya Gotta Ask – Reprise

Rex Stout’s “The Mother of Invention”

Dime Detective, August, 1941

John D. MacDonald’s “Ring Around the Readhead”

Harboiled Manila – Raoul Whitfield’s Jo Gar

7 Upcoming A (Black) Gat in the Hand Attractions

Paul Cain’s Fast One

Prior Posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2023 Series (15)

Back Down those Mean Streets in 2023

Will Murray on Hammett Didn’t Write “The Diamond Wager”

Dashiell Hammett – ZigZags of Treachery

Ten Pulp Things I Think I Think

Evan Lewis on Cleve Adams

T,T, Flynn’s Mike & Trixie (The ‘Lost Intro’)

John Bullard on REH’s Rough and Ready Clowns of the West – Part I (Breckenridge Elkins)

John Bullard on REH’s Rough and Ready Clowns of the West – Part II

William Patrick Murray on Supernatural Westerns, and Crossing Genres

Erle Stanley Gardner’s ‘Getting Away With Murder (And ‘A Black (Gat)’ turns 100!)

James Reasoner on Robert E. Howard’s Trail Towns of the old West

Frank Schildiner on Solomon Kane

Paul Bishop on The Fists of Robert E. Howard

John Lawrence’s Cass Blue

Dave Hardy on REH’s El Borak

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2022 Series (16)

Asimov – Sci Fi Meets the Police Procedural

The Adventures of Christopher London

Weird Menace from Robert E. Howard

Spicy Adventures from Robert E. Howard

Thrilling Adventures from Robert E. Howard

Norbert Davis’ “The Gin Monkey”

Tracer Bullet

Shovel’s Painful Predicament

Shovel’s Painful Predicament

Back Porch Pulp #1

Wally Conger on ‘The Hollywood Troubleshooter Saga’

Arsenic and Old Lace

David Dodge

Glen Cook’s Garrett, PI

John Leslie’s Key West Private Eye

Back Porch Pulp #2

Norbert Davis’ Max Latin

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2021 Series (7 )

The Forgotten Black Masker – Norbert Davis

Appaloosa

A (Black) Gat in the Hand is Back!

Black Mask – March, 1932

Three Gun Terry Mack & Carroll John Daly

Bounty Hunters & Bail Bondsmen

Norbert Davis in Black Mask – Volume 1

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2020 Series (21)

Hardboiled May on TCM

Some Hardboiled streaming options

Johnny O’Clock (Dick Powell)

Hardboiled June on TCM

Bullets or Ballots (Humphrey Bogart)

Phililp Marlowe – Private Eye (Powers Boothe)

Cool and Lam

All Through the Night (Bogart)

Dick Powell as Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar

Hardboiled July on TCM

YTJD – The Emily Braddock Matter (John Lund)

Richard Diamond – The Betty Moran Case (Dick Powell)

Bold Venture (Bogart & Bacall)

Hardboiled August on TCM

Norbert Davis – ‘Have one on the House’

with Steven H Silver: C.M. Kornbluth’s Pulp

Norbert Davis – ‘Don’t You Cry for Me’

Talking About Philip Marlowe

Steven H Silver Asks you to Name This Movie

Cajun Hardboiled – Dave Robicheaux

More Cool & Lam from Hard Case Crime

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2019 Series (15)

Back Deck Pulp Returns

A (Black) Gat in the Hand Returns

Will Murray on Doc Savage

Hugh B. Cave’s Peter Kane

Paul Bishop on Lance Spearman

A Man Called Spade

Hard Boiled Holmes

Duane Spurlock on T.T. Flynn

Andrew Salmon on Montreal Noir

Frank Schildiner on The Bad Guys of Pulp

Steve Scott on John D. MacDonald’s ‘Park Falkner’

William Patrick Murray on The Spider

John D. MacDonald & Mickey Spillane

Norbert Davis goes West(ern)

Bill Crider on The Brass Cupcake

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2018 Series (32)

George Harmon Coxe

Raoul Whitfield

Raoul Whitfield

Some Hard Boiled Anthologies

Frederick Nebel’s Donahue

Thomas Walsh

Black Mask – January, 1935

Norbert Davis’ Ben Shaley

D.L. Champion’s Rex Sackler

Dime Detective – August, 1939

Back Deck Pulp #1

W.T. Ballard’s Bill Lennox

Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Phantom Crook (Ed Jenkins)

Day Keene

Black Mask – October, 1933

Back Deck Pulp #2

Black Mask – Spring, 2017

Erle Stanley Gardner’s ‘The Shrieking Skeleton’

Frank Schildiner’s ‘Max Allen Collins & The Hard Boiled Hero’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Campbell Gault

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: More Cool & Lam From Hard Case Crime

MORE Cool & Lam!!!!

Thomas Parker’s ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’

Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part One)

Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part Two)

William Patrick Maynard’s ‘The Yellow Peril’

Andrew P Salmon’s ‘Frederick C. Davis’

Rory Gallagher’s ‘Continental Op’

Back Deck Pulp #3

Back Deck Pulp #4

Back Deck Pulp #5

Joe ‘Cap’ Shaw on Writing

Back Deck Pulp #6

The Black Mask Dinner

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’).

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE Definitive guide to Conan. He also organized 2023’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, and XXXIII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.