Truth, Lies, and Vinyl Wonderland

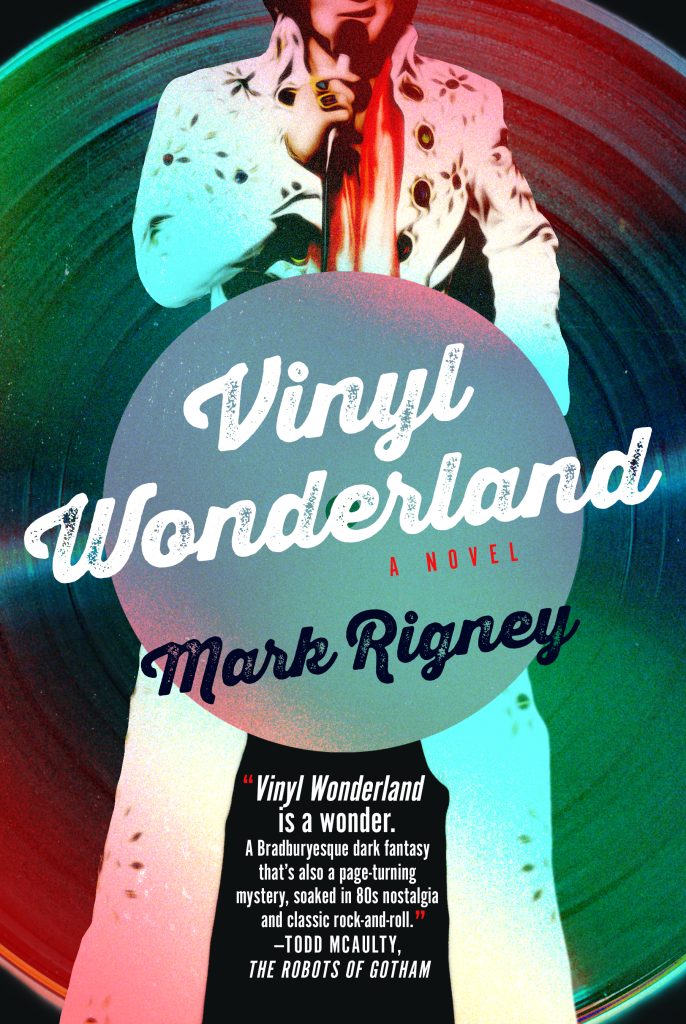

Vinyl Wonderland (Castle Bridge Media,

June 25, 2024). Cover uncredited

Some months back, I was toiling away in the vast Indiana compound of Black Gate, when I received a text from publisher John O’Neill, who had just finished reading my new novel, Vinyl Wonderland. He told me how much he enjoyed it –– don’t take my word for it, ask him –– and then he told me how sorry he was.

“What for?” I asked.

“Well,” said John, “if you had to live through even half of what your main character went through, then you’ve had one hell of a rough ride.”

I thought about what John had said as I made my nightly rounds of the massive server farm that houses all of Black Gate’s backlogged posts (including over one hundred of mine). Eventually, I crawled off to bed, feeling hopeful that the local kobolds wouldn’t stage another uprising until next month, so that I could get a good night’s rest.

The morning brought clarity, as it often does, and I sat up in bed like a shot. “A liar,” I declared, quoting Quintilian, “should have a good memory!”

Fiction is a lie, after all, spun from gossamer truths, and therefore I, as a writer of fiction, must be a liar. It follows that to succeed in my craft, I must cultivate an excellent memory. Logic (and Quintilian) demand it.

What I really mean by lying, in the realm of fiction, is observing. At least for John, I observed the particulars of the real world well enough that I was able to transcribe them convincingly into Vinyl Wonderland.

But what’s really striking is that I apparently lied sufficiently well to convince John that I had myself experienced a significant number of the book’s traumatic events –– that I’d suffered through them in what is now frequently referred to as “lived experience.” The violent death of a parent, for example, while growing up. Totally dysfunctional in-the-home alcoholism.

Here’s the rub: as a savvy reader and a smart, canny adult, John would never have made the same assumptions about me had he been reading alternate-world fantasy or future-set science fiction.

Consider the opening lines of The Trade, available right here in Black Gate’s online fiction library:

Gemen the Antiques Dealer arrived in Andolin late in spring, the year after that nation’s disastrous civil war had lumbered to a close. He spoke the language tolerably well, but always with an accent that some claimed hailed from the far west, while others insisted it smacked of the South: Melony, or even the Thornlands, where the sun burned people’s eyes the color of molten copper.

We’re two sentences in, and already, any reader past the point of naming Barney the Purple Dinosaur as their favorite novel will already find clues aplenty that this story takes place elsewhere and probably elsewhen, with the result that said reader will at once cease to worry whether the author actually had to deal with any of the story’s situations first-hand. The reader understands that the writer is lying from the word go.

Conversely, readers of A Complicated Kindness by Miriam Toews can hardly help but wonder, did the author, like her main character, grow up in an isolated Canadian town, immersed in a Mennonite version of a failing charismatic cult? If she did, how awful for her. But if she did not, then how did she pull off her story with such apparent verisimilitude?

And, if she grew up in some other situation, does that not make Toews a consummate liar?

Ultimately, then, it’s not my skills as a liar or a prose-writer that led John to form the question of whether I had suffered through the same troubles as Vinyl Wonderland’s protagonist. It’s the particular set of textual markers and signposts –– the semiology, if you will –– that allow for those questions to arise in the first place. Titles such as The Bluest Eye, The Round House, or We Were the Mulvaneys invite these comparisons. Others, like Watership Down, The Fifth Season, or “Love is the Plan, the Plan is Death,” all but forbid them.

Vinyl Wonderland is a hybrid. Like “The Small Assassin,” Kindred, and Interview with a Vampire, its fantasy elements are firmly embedded in a real-world setting, thus allowing readers the kinetic pleasures (or so I hope) of traversing the speculative realm while still focusing its concerns on the tricky, compromised reality in which we actually live. In so doing, it invites questions like John’s. It invites readers to extend their curiosity outward from the pages and into the life of the author.

As for where Vinyl Wonderland originated, I was at a low point in my writing life. COVID-19 had stopped my playwriting world in its tracks, and the arts in general were at a standstill. I decided I needed to write something quickly, as a self-imposed dare. I gave myself three months to get from the first blank page of this as yet un-named manuscript to “The End.”

As I saw it, the only way to succeed was to “write what I know,” really just as a time-saving measure, a way of reducing the total level of invention required. So, I did three things very deliberately. First, I set the book in Columbus, Ohio, where I grew up, and second, I chose the time-frame of the mid-1980s (inspired sub-consciously, I’m sure, by Stranger Things).

Third, I pirated an idea I’d already developed in two previous short stories. The first of these, “Joey’s Zona Cero,” appeared in a one-off anthology, Escape Clause (Ink Oink Art, 2009), and the second, “Mayor of a Flourishing City,” came out in Betwixt (Issue 1, Fall 2013). Betwixt’s editor, Joy Crelin, later reprinted “Joey’s Zona Cero,” and those two stories are archived on-line HERE and THERE, respectively.

The result was a very speedy draft, completed “on time,” and then roundly ignored by agents and publishers for two-and-a-half years.

But then Castle Bridge Media arrived on the scene to provide literary CPR, and the rest, as they say, is history.

So, as I make my way tonight through the astonishing array of the Black Gate server farm, dusting occasionally, humming to myself, I have decided that I am very well pleased with John’s reaction.

There are worse things in life than being called a liar.

Mark Rigney is a writer and long-time Black Gate blogger. His work on this site includes original fiction and perennially popular posts like “Youth in a Box.” His new novel, Vinyl Wonderland, dropped on June 25th, 2024. His favorite review quote by far comes from Instagram: “Holy crap on a cracker, it’s so good.” A preview post can be found HERE, while his website lives over THERE.

Bookmarked as a favorite essay. Truths among lies, that altogether make me smile. Bravo.

Very kind of you to say so! However, and at the risk of tooting my own horn, I guarantee the book is better than this essay.

: )