Worthy of His Hire: The Day’s Work by Rudyard Kipling

The Day’s Work (Penguin Classics, October 4, 1988)

I spent most of my childhood and adolescence in a house with large built-in bookshelves, occupied by books passed on from my grandmother. Among the ones I read were multiple volumes by Kipling. One of the more memorable was The Day’s Work, which I recently added to my shelves of print fiction and which I’ve just reread: a collection of stories nearly all written during Kipling’s period of residence in Vermont, during the early 1890s.

A long time ago, I ran across a comment by some critic that if you wanted to read a conversation between a god, an animal, and a machine, Kipling would be the perfect choice to write it. The Day’s Work might be taken as evidence to support this; it doesn’t bring the three together, but it has one story with a conversation among gods, “The Bridge-Builders”; two with conversations among horses, “A Walking Delegate” and “The Maltese Cat”; and two with conversations among machines, “The Ship That Found Herself” and “.007,” the latter being about a locomotive newly put into service. Those five stories, out of a total of twelve, give the collection a strong feeling of fantasy, which must have been part of what appealed to me when I was in elementary school.

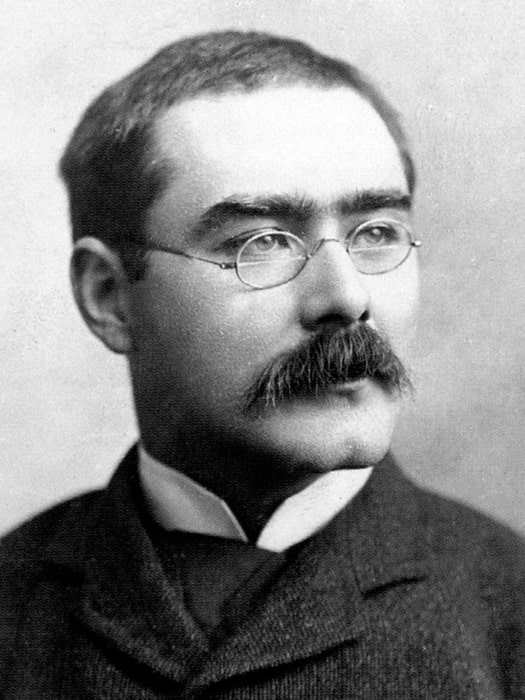

Rudyard Kipling

Here’s the full list of stories.

“The Bridge-Builders”

“A Walking Delegate”

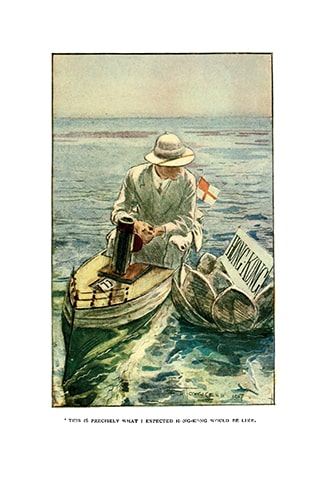

“The Ship That Found Herself”

“The Tomb of His Ancestors”

“The Devil and the Deep Sea”

“William the Conqueror”

“.007”

“The Maltese Cat”

“‘Bread upon the Waters’”

“An Error in the Fourth Dimension”

“My Sunday at Home”

“The Brushwood Boy”

When I first read this, my favorite story was “The Maltese Cat.” The title is the name given to a polo pony, and the entire story is an account of a polo match from the viewpoint of the horses — written as if the horses understand the rules of the game and are acting according to a conscious strategy. (I’ve read that this narrative convention goes back to ancient Rome charioteering.) The Cat starts out saying to the other ponies that “we must play together, and you must play with your heads.”

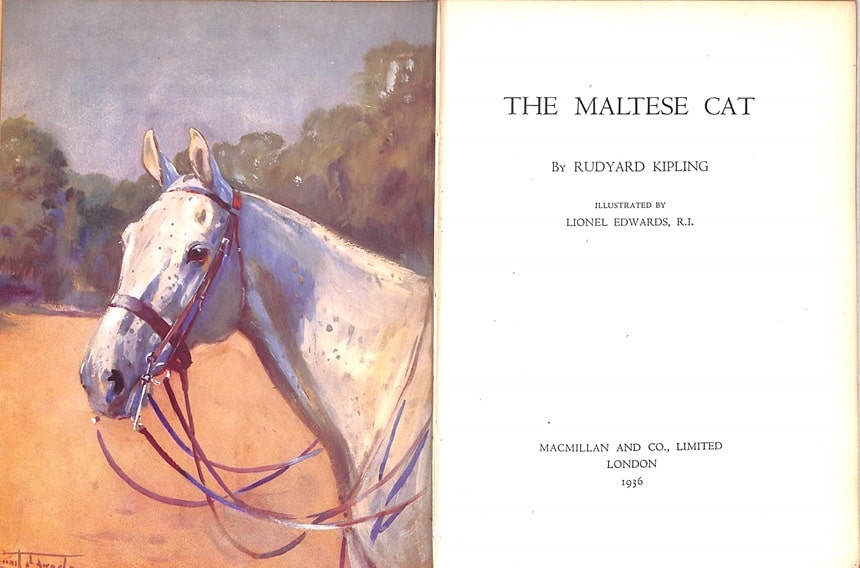

“The Maltese Cat,” illustrated by Lionel Edwards

Kipling’s imaginary polo match is the final contest of an open competition for teams from all of Upper India, which will decide the championship. The Maltese Cat’s team, the Skidars, are the underdogs, with only twelve ponies for six quarters, meaning that each pony will have to play in two quarters rather than one. On the other hand, their opponents, the Archangels, are “a team of crack players instead of a crack team,” which — this is one of Kipling’s main points — gives the Skidars an important advantage.

Kipling’s narrative structure shows a good sense of proportionality: he shows the first three quarters in detail, play by play — and makes them interesting even for a reader who knows nothing of polo! — and then skims quickly over the fourth and fifth to come to the high-intensity sixth, which starts with the two teams tied, and with the Skidars’ captain, Lutyens, playing with a broken collarbone, not having a capable enough substitute. This makes the effective teamwork, not only between the players, but between Lutyens and the Cat even more vital to the outcome.

Now, as an adult, the story I love above all the others is “William the Conqueror.” This is a purely human story of a type Kipling seldom wrote: a love story. “William” is its female lead character, a young woman of twenty-two, living with her brother in India, who has turned down many suitors, and whom Kipling carefully avoids glamorizing. (She “wore her hair cropped and curling all over her head,” and “in the center of her forehead was a big silvery scar about the size of a shilling” from an infection caught by drinking bad water.)

At the start of the story, William’s brother and his close friend Scott are transferred temporarily to the south of India on famine relief, and William goes along, ignoring their objections. Most of the rest of the story is William and Scott doing extremely hard and often unsuccessful work, hardly ever seeing each other, but learning each other’s value. Their key conversation, near the end, shows not the kind of small misunderstanding that leads to disaster in more than one of Kipling’s stories, but its opposite: a small understanding that doesn’t need to be made explicit to be compelling.

“I like men who do things,” she had confided to a man in the Educational Department . . . and another broken heart took refuge at the Club.

– “William the Conqueror”

The title of the collection, as is usual with Kipling’s books, is more allusive than exact. Still, by my count, at least seven of the stories are about men, or animals, or machines at work. “A Walking Delegate,” the lesser horse story, might count as eighth, being one of Kipling’s slightly too explicit political allegories — in this case, about labor activism: not a portrayal of work but a kind of sermon about work.

The opening story, “The Bridge-Builders,” might be taken as showing the triumph of work, with Mother Gunga, the goddess of the Ganges, in the shape of a crocodile, complaining of the English chaining her with a bridge, and pleading with the other gods to bring it down, and Hanuman admiring the English and recalling his own days as a bridge-builder.

|

|

|

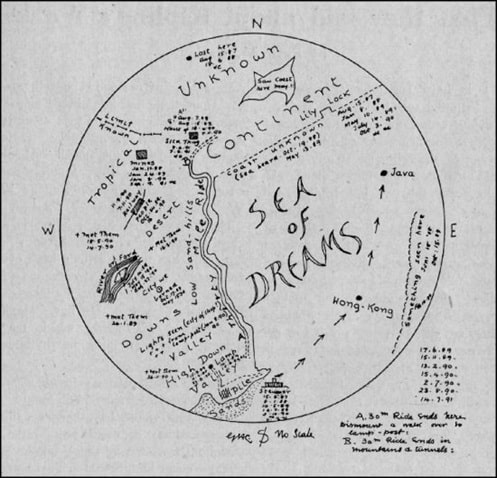

Illustrations for “The Brushwood Boy”

In contrast, though the final story, “The Brushwood Boy,” does show its protagonist, George Cottar, at work, as a new subaltern in an Indian regiment, work isn’t what it’s about; it’s there as counterpoint to George’s dreams. Some of these are a series of visits to a surreal but consistent dream world, where he is often accompanied by a companion, who appears first as a small girl and then, near the end, as a young woman. (George has been slow in paying attention to women, and has completely failed to notice when an older, married woman on the voyage home tried to seduce him.) Then, at the story’s end, he discovers that he isn’t the only person who has been dreaming those particular dreams — which makes this story another work of fantasy. The discovery is triggered by one of the bits of verse that Kipling sometimes embeds in his stories, and had the skill to make creditable.

I don’t think all of the stories in this book are equally good: “A Walking Delegate” and “.007” both are lesser stories than their companion horse and machine stories (curiously, “The Ship That Found Herself” is actually a stronger story for its allegory), and “My Sunday at Home” leaves me confused about Kipling’s narrative point. But having just reread this collection through, I think the back cover of my copy is justified in calling this “one of Kipling’s best collections of stories.”

William H. Stoddard is a professional copy editor specializing in scholarly and scientific publications. As a secondary career, he has written more than two dozen books for Steve Jackson Games, starting in 2000 with GURPS Steampunk. He lives in Lawrence, Kansas with his wife, their cat (a ginger tabby), and a hundred shelf feet of books, including large amounts of science fiction, fantasy, and graphic novels. His last article for us was a review of The Wages of Sin by Harry Turtledove.

I read a fair bit of Kipling’s short stories when I was younger. I think he’s probably underrated today.

I think you can make a strong argument for Kipling as the greatest English writer of short stories in the 20th century. (And, of course, he is English but also (sort of) Indian and even slightly American, which is for him a strength.) I think of The Day’s Work as a transitional collection, between his Indian period and his late period.

I think his greatest stories come from the “late” period (which is to say, essentially, the 20th Century) — “Mrs Bathurst”, “The Janeites”, “The Gardener”, “Dayspring Mishandled”, “Marklake Witches”, “‘They'”, “Mary Postgate”, “Swept and Garnished” and several more. But I’d agree that The Day’s Work is one of his best earlier collections. My favorite of the book is “The Brushwood Boy”, but I agree that “The Maltese Cat” and “William the Conqueror” are also very fine.

My favorites don’t include any of those, though I do find “Dayspring Mishandled” quite good. But I would pick “Lispeth,” “Love-o’-Women,” “A Church There Was at Antioch,” “The Miracle of Purun Bhagat,” “William the Conqueror,” “As Easy as A.B.C.,” and perhaps “The Maltese Cat” and “His Wedded Wife” as special favorites.

One of my two current roleplaying campaigns takes its premise of shared lucid dreams primarily from “The Brushwood Boy.”

I haven’t read any of these, but I’m currently reading through the whopping Everyman edition of Kipling’s collected stories and I agree with Rich – the man was a stupendous short story writer. A few years back I read the Jungle Book for the first time, and was blown away by it; it definitely wasn’t Disney. It was more like Shakespeare.

The first Kipling book I read after “The Jungle Book” and “Just So Stories” and it knocked me off my ass. For my money he remains the greatest story writer (whatever one’s definition) in the English language. It’s nothing less than crimminal that he isn’t more widely read and discussed these days but I suspect some future variation of our culture will circle back to him. It’s really a pity more of his work hadn’t been filmed. You could literally stuff the pages into the camera lens.

Disapproval of Kipling goes a long way back. I have a collection of his verse edited by T.S. Eliot, who apologizes for liking him; George Orwell also apologized for liking him, in a review of Eliot’s collection, and disapproved of Kipling’s moral and political values; W.H. Auden wrote about “Time, that with this strange excuse/Pardoned Kipling and his views” (the strange excuse being Kipling’s mastery of language). The offense seems to have been that Kipling thought the British Empire was a good thing. I’m sure there were many people back then who simply refused to read him, and there may be more now; Neil Gaiman has written about people who were horrified that he had anything positive to say about Kipling.

I like both his stories and his verse, from his early “The Mary Gloster,” a monologue in the style of Browning, to his late and moving “Hymn of Breaking Strain.”

Thank God there are still a few freaks in the world who believe that, generally speaking, the least interesting thing about people is their politics.

I believe that in recent decades people — many of them on the left — have more and more come around to the view that no matter what you think of Kipling’s politics (and I do think he held some repugnant views, though not so many as some people claim) his fiction, his writing, is remarkable and deserves to be read.

Yes, there are still people who reflexively reject him, but fewer than there once were.

I think the primary reason he was for a time so neglected was his politics, but an additional reason was a persistent suspicion of work that is popular by high-culture critics. That suspicion tends to fade over time in general. (See: Shakespeare, Dickens, even Trollope.)

Kipling is excellent!