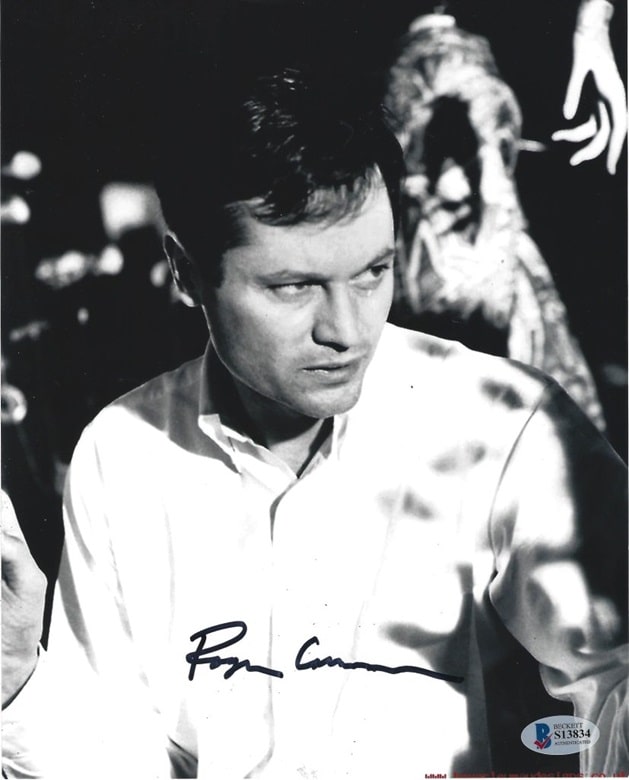

Roger Corman, April 5, 1926 – May 9, 2024

Roger Corman, the Godfather of American independent film, is gone. He died at his home in Santa Monica, California, on May 9th. He was ninety-eight.

Legendary both for his cheapness (no one could squeeze more out of a budget than he could) and for his generosity (he gave countless actors, directors, writers, and technical people their first chance in Hollywood), Corman began his almost seventy-year long career in the mid 50’s by directing extremely low-budget movies for the fledgling American International Pictures, most of which were shot in one or two weeks for less than 100,000 dollars. Corman’s understanding of the necessity of ruthless economy on the one hand and of the appetites of his largely teen-aged audience on the other made these films highly successful, and during those early years, that success was perhaps the major factor in establishing AIP as an ongoing concern.

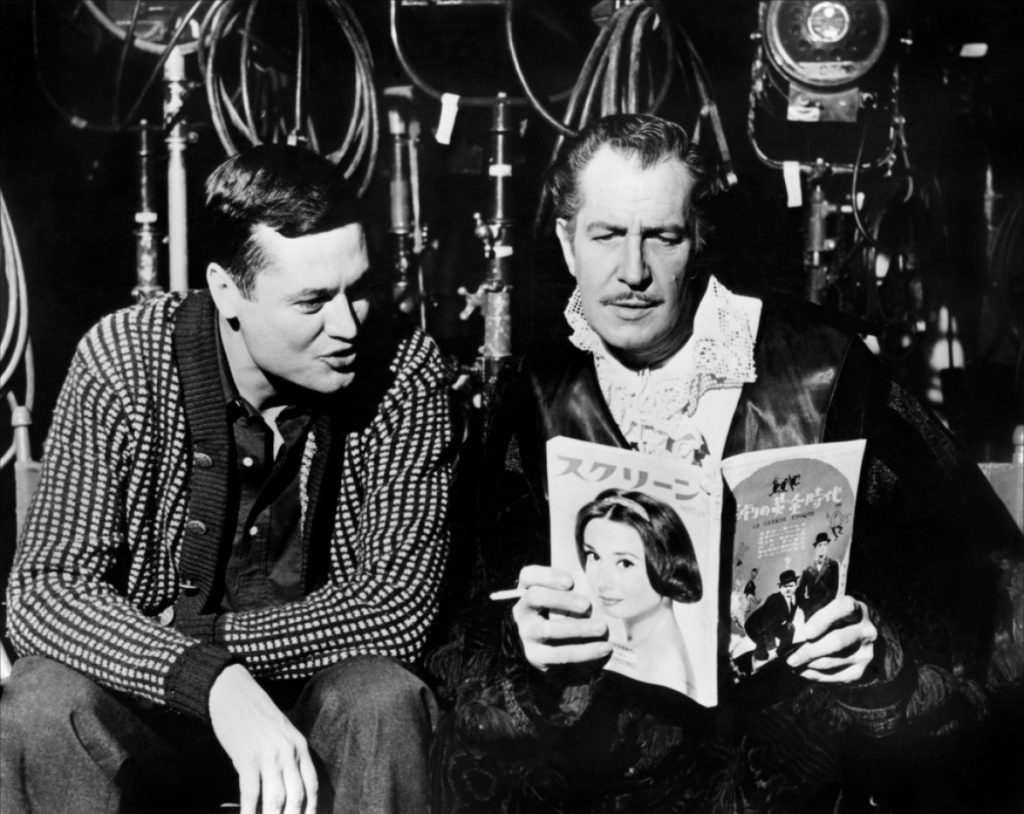

Even Corman’s cheapest, most hurried work showed a degree of innovation, imagination, and ambition that were unusual in low-budget films of that era, and he quickly graduated to somewhat more expensive pictures, the most celebrated of which are the eight visually flamboyant, wildly Freudian Edgar Allan Poe adaptations that he directed from 1961 to 1964, seven of which starred Vincent Price. The best of them are probably The Masque of the Red Death and The Tomb of Ligeia, both 1964; the first is my favorite of the Poe cycle and the second is Martin Scorsese’s. Between the two of us, you can’t go wrong.

Corman’s best-remembered movies are his many science fiction and horror offerings, but his restless, rebellious refusal to settle on any one thing led him to try his hand at almost every genre; in his fifteen years as an active director, western, sword-and-sandal, social problem, gangster, war, rock and roll, offbeat comedy and teenage delinquent films all received the Corman treatment.

In 1970, Corman left AIP and himself became a cut-rate mogul by founding New World Pictures. (The last straw was when the AIP brass changed the ending of his LSD movie The Trip without his consent; the ever-independent Corman vowed that he would never submit to such treatment again.) By this time he had largely stopped directing, contenting himself with acting as producer for a never-ending outpouring of exploitation fare, while at the same time using New World to import and distribute the best European art films (Fellini and Bergman were his personal favorites), a task which other studios had largely abandoned. He spent his last decades presiding over his low-budget empire as an increasingly revered elder statesman, a man who had been hugely important in the last three quarters of a century of American film, a period of movie history which would have been radically different without him.

Roger Corman’s place in that history is secure. He was a universally-acknowledged father of the “New Hollywood” that succeeded the decaying studio system in the 1960’s, because so many people who shaped that looser, freer, more independent and iconoclastic Hollywood came out of the so-called “School of Corman.”

Before he directed The Godfather, Francis Ford Coppola directed Dementia 13 for Corman; before he wrote Chinatown, Robert Towne wrote The Last Woman on Earth for Corman; before he directed The Last Picture Show, Peter Bogdonovich directed Targets for Corman; before he acted in One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Jack Nicholson acted in The Raven for Corman; before he directed Mean Streets, Martin Scorsese directed Boxcar Bertha for Corman. These examples could be multiplied almost indefinitely; Jonathan Demme, Robert DeNiro, Peter Fonda, Bruce Dern, Joe Dante, John Sayles, James Cameron, Pam Grier, Dennis Hopper, Ron Howard — all got a hand up from Roger Corman. (Many of his alumni returned the favor by tapping him to act in their films; he lent his distinguished presence to The Godfather Part II, The Silence of the Lambs, Philadelphia, The Howling, and Apollo 13, among others.)

Corman’s importance was finally officially recognized by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 2009, when they awarded him an Oscar to honor his life’s work in both making films himself and in nurturing several generations of filmmakers; that night the establishment did homage to the insurgent, and everyone present seemed truly delighted.

Movie moguls are notoriously unlovable figures; when Columbia’s abrasive Harry Cohn died, a wit attending his funeral looked around at the packed church and quipped, “If you give the people what they want…” Roger Corman was a maverick in every way, though, and he even bucked the Harry Cohn Hollywood tradition — he died one of the most genuinely loved men in the business. In the terrific 2011 documentary Corman’s World: Exploits of a Hollywood Rebel, David Carradine said,

I’m actually a little tongue-tied when I’m around Roger. I just have — you know, we’re completely different kinds of people, and I have such respect for him. You know, once in a while Roger would come to my rescue, pretty much, you know, when things were — nothing was happening.

Carradine also related a conversation that illustrates Corman’s… well, let’s not say economy or frugality — of the dead, nothing but the truth — it illustrates Corman’s cheapness:

If he just violated this rule of his of never making a movie that cost more than one million dollars, you know, make one for a million and a half or two million dollars, I said, “Look, all your movies make money. None of them go through the top.” And he said, “Yeah. That’s true.” And then he went over and turned off the air conditioner.

Jack Nicholson also appears in Corman’s World, telling stories of the days when the world was young, and he breaks down in tears near the end, when he says this of his lifelong friend:

I mean, there’s nobody in there that he didn’t in the most important way support. He was, you know, my main connection — my lifeblood — to whatever I thought I was gonna be as a person. And you know, I hope he knows that this is not all hot air. I’m gonna cry now… not just me, who’s very sentimental, but these other people also love him. Sorry.

Speaking of when the world was young, Roger Corman was one of the last remaining links with a grindhouse, drive-in, weird movies-on-late-night-TV world that has vanished forever, never to return. I saw my first Corman movie, The Little Shop of Horrors, flickering on my television screen one midnight in the late 60’s or early 70’s; it was the beginning of a love affair that has lasted for over fifty years. One of the high points of my life was the time in high school when one of our local Los Angeles independent stations aired The Masque of the Red Death every night for an entire week. In those pre-home video days, it didn’t get any better than that.

Part of getting older is a growing familiarity with the world “without.” I now have to face — we all have to face — the world without Roger Corman. I can’t yet wrap my head around what that will be like, knowing that he’s not out there anymore. But I have his movies to get me through; they’re not going anywhere. Just a couple of weeks ago, I was joined by a friend (a fellow Cormanite like myself — we’re everywhere, like the pod people in Invasion of the Body Snatchers) to watch Corman’s wild beatnik satire A Bucket of Blood, and as we watched, in between our laughter, we continually remarked how good the movie was — how well shot, how well acted, how funny and lively and better than it had any right to be it was. That surprising quality wasn’t an accident — it was Roger Corman.

School ends for me in just a couple of weeks, and my summer vacation begins. I know how I’m going to spend it — I’m going to have a great big Roger Corman film festival. Come on by; I guarantee you’ll have a blast.

When Roger Corman received his Oscar in 2009, Quentin Tarantino made a speech, thanking the King of the B’s for all that he had done. I can’t better Tarantino’s words:

The Academy thanks you. Hollywood thanks you. Independent filmmaking thanks you. But most importantly, for all the wild, weird, cool, crazy moments you’ve put on the drive-in screens, the movie lovers of the planet earth thank you!

Amen. I can only add my thanks to Tarantino’s, and say, good night, sweet prince, and don’t forget to turn off the air conditioner.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was A Reckless and Unwarranted Speculation on the Origin of a Great Science Fiction Story

A fine send-off. Well done.

My connection to Corman is through food. I worked for one week-long shoot at his studios in 1992 or 93, can’t remember which. Nor can I recall the name of the film! I was hired to do craft services, which in Hollywood-speak means: the person who feeds cast and crew. I remember arriving at the studio, I believe it was in Venice, behind a chain-link fence, and being shown my “kitchen.” It had a counter and running water and cabinets. Some utensils. A few mugs, some crockery. There was no way to heat food. I had a per diem budget, incredibly small, but I asked if I could buy a hot plate, and the producer/tour guide said, sure, as long as you don’t go over budget. So, on day one, I bought a hot plate and a pile of canned soup. I was immediately the biggest hit on the lot, since most of the employees had worked for Corman before, and couldn’t believe they had the option of hot soup–which believe you me, in Southern California, that close to the beach, is a good thing. It’s rarely hot, and if I remember right, it was autumn. Anyway, the shoot ran for I think it was five days, might have been six, an incredibly short time-frame to put a feature in the can, but that’s how Corman did it, and on the first day, it started at eight a.m. The call for day two was bumped two or three hours ahead, and so on, so that by the final day, the shoot was an overnight. It was brutal. Those last couple of work days were like changing time zones in three-hour jumps, every single day. They wanted me back (because of the Great Hot Plate Innovation), but I said no. The money was lousy and those hours wrecked me. One nice perk: I got to meet (and feed) John Hollis, who played Lando’s aide-de-camp in “Empire Strikes Back.” John liked chocolate, and I got him a private stash of mini Hershey bars, which he was so grateful for. And at one point, during an indoor scene, they were having trouble getting good audio on the actors, and they remembered I’d run a Nagra before, and used boom poles, etc., so I was called in to help with a boom mic. I never met Corman (pretty sure he never showed up that entire week), but I got the inside experience. Memories!

This is the day we’ve dreaded and anticipated; now we have an excuse–nay, an imperative–to watch Corman’s vast catalogue of films.

His work has entertained me no end. I’ve laughed at crude monsters and goofy dialogue, even as I’ve marveled at the quality of filmmaking where it shouldn’t exist on such a budget. I’ve seen Corman B-Movies that work ten times as hard as Hollywood blockbusters and turn out a darn good story. I’ve seen the seminal works of directors, writers, and actors thanks to Corman, and marveled at how he saw something in them that became obvious to the rest of us years or even decades later.

A tribute to Corman’s filmography is going to make for a full summer, but by God, it’ll be a fun one.