A Reckless and Unwarranted Speculation on the Origin of a Great Science Fiction Story

Alice (James Tiptree Jr.) Sheldon

Alice (James Tiptree Jr.) Sheldon

For many writers, asking them the apparently innocent question, “where do you get your ideas?” is like waving a red flag in front of a bull. (Watch the Harlan Ellison documentary Dreams with Sharp Teeth for a great example; at the very thought of someone posing that question, Ellison goes from zero to apoplexy in 1.2 seconds. I know — Harlan Ellison, but still…)

Nevertheless, as a humble reader to whom the mysteries of creative writing are forever veiled, it’s a question that I’m curious about. Having never met Alice (James Tiptree Jr.) Sheldon, I have no idea how she would have reacted to the question, and I’ll never find out, as she died in 1987… but I think I know the answer for one of her stories, at least.

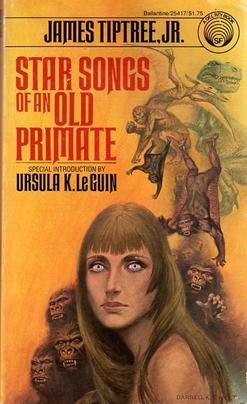

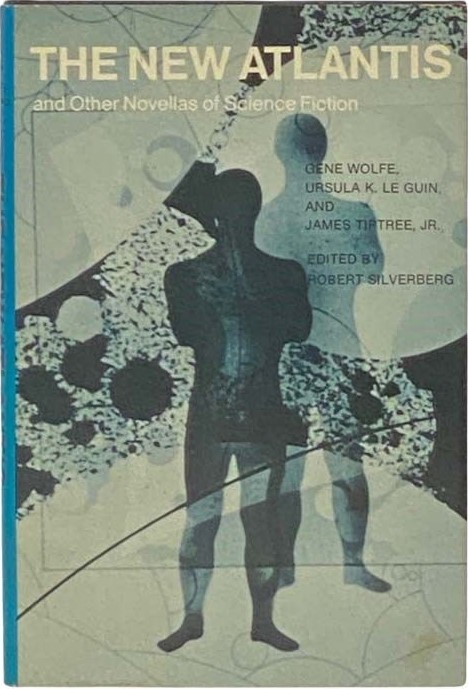

Alice Sheldon (under the whimsical pseudonym that she and her husband cooked up) was a science fiction writer without peer, and her novella A Momentary Taste of Being, which first appeared in 1975 in the Robert Silverberg-edited anthology The New Atlantis (and later in her own collection Star Songs of an Old Primate and the “Essential Tiptree” anthology Her Smoke Rose Up Forever, which you should buy immediately, forgoing food and rent if necessary), is one of her greatest stories, a radical premise pushed to its absolute limits… and I believe I know where that wild premise came from.

The story is set in the future on the deep-space exploration vessel Centaur. The ship’s mission is to find a habitable planet for human colonization; the seething, overcrowded earth is bursting at the seams, and the pressure is growing more intolerable every day. Narrated by the Centaur’s physician Aaron Kaye, the novella chronicles the finding of a potentially viable planet, but what should be a triumphant, “mission accomplished” moment turns out not to be what the crew expected; the success they achieve is far different from the one they had envisioned.

The story is set in the future on the deep-space exploration vessel Centaur. The ship’s mission is to find a habitable planet for human colonization; the seething, overcrowded earth is bursting at the seams, and the pressure is growing more intolerable every day. Narrated by the Centaur’s physician Aaron Kaye, the novella chronicles the finding of a potentially viable planet, but what should be a triumphant, “mission accomplished” moment turns out not to be what the crew expected; the success they achieve is far different from the one they had envisioned.

Ten years into the voyage, the Centaur, with its crew of sixty, approaches Alpha Centauri and its three planets. While the ship is still far from the system, it sends out three smaller survey vessels to report on these worlds; they each take a year to reach their target planet and another year to return with their assessments. Two ships come back with bad news — their worlds are not suitable for human habitation. The third ship makes a different report.

The third planet is perfect in every way, is, in fact, almost literally paradise, so much so that only one of the survey crew was willing to return to the Centaur, the rest of the group choosing to remain on the new world to immediately begin their lives as colonists. Aaron’s younger sister Lory is the only explorer to come back, bearing the exciting news… and something else as well.

She has brought back from the planet, sealed in the hold of her scout ship, an alien life form of incredible beauty. She has been completely isolated from this seemingly plant-like thing during her return, going so far as to weld shut the only viewing port through which she could have observed it. She didn’t want to even look at this gorgeously glowing, deeply alluring, and (as she asserts over and over) completely harmless thing. She had to protect herself from the very sight of it — why?

The Centuar’s captain decides to continue on to the planet (a voyage that will take another two years) for fuller verification before sending the unrecallable “green light” signal to earth. Two crew members do not agree with this cautious decision, however, and they send the signal themselves. For good or ill, earth is coming.

After Lory has spent several days being thoroughly decontaminated and debriefed, it is time to remove the alien life form from the scout ship for examination. All precautions are taken — but when the scout ship docks with the Centaur and the hold containing the alien is opened, all precautions go for naught. As the bioluminescent entity’s dazzling light floods the corridor where the examination is to take place, every person present — and everyone watching on monitors throughout the ship — is irresistibly drawn to the thing (which explains Lory’s totally isolating herself from it).

Buy it. Buy it NOW

The members of the examination team present in the corridor tear off their helmets and rush into the hold, quickly followed by the rest of the crew, who have come from all parts of the ship, charging through security doors that were supposed to have been sealed and guarded — but the guards are with the alien too. Once in the hold, the Centaur’s bewitched crew members are drawn to press their foreheads to the thing’s glowing body…

Eventually people start coming out of the hold, but contact with the alien has done something to them. They are quiescent; they leave the creature drained, stunned and empty. They seem, in fact, to be in some deep way, finished.

Aaron Kaye is the only member of the Centaur to successfully resist the overwhelming pull, though it takes everything he has to keep himself out of the hold. After the alien-bearing scout ship is flown away by a crew member determined to get to the planet itself — the source of such glory — the erstwhile physician is left alone on the Centaur, alone with the vacant, dying husks that were once his shipmates and friends.

Aaron Kaye is the only member of the Centaur to successfully resist the overwhelming pull, though it takes everything he has to keep himself out of the hold. After the alien-bearing scout ship is flown away by a crew member determined to get to the planet itself — the source of such glory — the erstwhile physician is left alone on the Centaur, alone with the vacant, dying husks that were once his shipmates and friends.

Or not entirely alone, because the Centaur is now also occupied by something else, something new that Aaron calls “ghosts” for want of a better word:

They’re more or less transparent, of course, even at the end. They float. I think they’re partly out of the ship. It’s hard to tell their size, like a projection or afterimage. They seem big, say, six or eight meters in diameter, but once or twice I’ve thought they may be very small. They’re alive, you can tell that. They don’t respond or communicate. They’re not… rational. Not at all. They change, too, they take on colors or something from your mind. Did I say that? I’m not sure they’re really visible at all, maybe the mind senses them and constructs an appearance. But recognizable. You can see… traces. I can identify most of them.

After a short time, these things that seem to contain “echoes” of the Centaur’s crew leave the ship and vanish into space. What are they? What has happened? Doctor Aaron Kaye thinks he knows. “What I think they are is blastomeres.” (For those who have forgotten their high school biology, a blastomere is a type of cell produced by cell division of the zygote after fertilization.)

In the ever-essential Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, John Clute sums it up succinctly: “The human race, en route to the stars, discovers that its racial role is to act as gamete in a cosmic coupling, and that the drives that make us human are merely displacements of that central mindless imperative.”

Aaron puts it this way, in the increasingly alcohol-soaked musings that he records on the dead ship:

Nothing but gametes. The dimorphic set — call it sperm. Two types, little boy sperms, little girl sperms — half of the germ-plasm of… something. Not complete beings at all. Half of the gametes of some… creatures, some race. Maybe they live in space. I think so. The, their zygotes do. Maybe they aren’t even intelligent. Say they use planets to breed on, like amphibians going to the water. And they sowed their primordial seed-stuff around here, their milt and roe among the stars. On suitable planets. And the stuff germinated. And after the usual interval — say three billion years, that’s what it took us, didn’t it? — the milt, the sperm, evolved to motility, see? And we made it to the stars, to the roe-planet. To fertilize them. And that’s all we are, the whole damn thing — the evolving, the achieving and fighting and hoping — all the pain and effort, just to get us there with the loads of jizzum in our heads. Nothing but sperm’s tails. Human beings — does a sperm think it’s somebody, too? Those beautiful egg-things, the creatures on that planet, evolving in their own way for millions of years… maybe they think and dream too. Maybe they think they’re people. All the whole thing, just to make something else, all for nothing —

Damn.

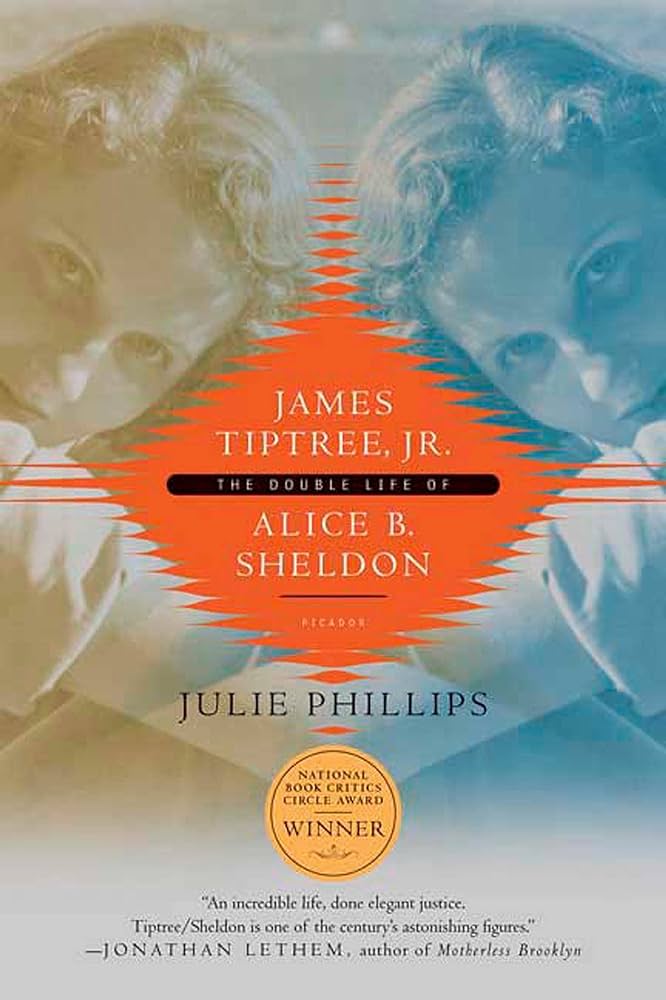

In her excellent 2006 biography, James Tiptree Jr. The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon, Julie Phillips tries to soften the blow by declaring that the story “surely has an element of black comedy.” If there is comedy of any shade in A Momentary Taste of Being I confess I am unable to find it. It is, from start to finish, a terrifying, shockingly desolate and devastating vision of human existence. (The only fault I can find in Phillips’ fine book is a tendency to look away from the bleak, remorseless logic of Alice Sheldon in an understandable effort to infuse the Tiptree canon with a gleam of optimism, optimism that I just don’t think is there.)

In her excellent 2006 biography, James Tiptree Jr. The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon, Julie Phillips tries to soften the blow by declaring that the story “surely has an element of black comedy.” If there is comedy of any shade in A Momentary Taste of Being I confess I am unable to find it. It is, from start to finish, a terrifying, shockingly desolate and devastating vision of human existence. (The only fault I can find in Phillips’ fine book is a tendency to look away from the bleak, remorseless logic of Alice Sheldon in an understandable effort to infuse the Tiptree canon with a gleam of optimism, optimism that I just don’t think is there.)

I agree with John Clute; A Momentary Taste of Being (the title comes from the Edward Fitzgerald translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: “A momentary taste/Of Being from the Well amid the Waste”) is “one of the darkest genre-sf stories ever printed.” I know that I’ve never read a darker one; I wouldn’t want to.

Where did this soul-blighting, utterly comfortless vision come from? Phillips provides a clue. Alice Sheldon, she tells us, was a huge Star Trek fan; she “developed a violent crush on Spock” and “wrote a long fan letter to Leonard Nimoy explaining Spock’s appeal.”

She even wrote a script for the show, but Star Trek’s producers returned “Meet Me at Infinity” unread, saying that they didn’t accept scripts unless they were submitted through an agent. Sheldon asked Fred Pohl’s help in getting the script looked at, but Pohl dissuaded her from trying, and that was that. (I have been unable to find out if the script still exists; I know that I would kill to read it.)

In any case, finding out that Alice Sheldon loved Star Trek is like discovering that when Jim Morrison wasn’t exposing himself on stage with the Doors, he got off by listening to the Partridge Family. It’s a very strange conjunction, but a real one, and I believe that one of the most despair-soaked stories ever written had its origin in an episode of one of the most optimistic, upbeat television shows ever aired. (I think Sheldon loved Star Trek precisely because its sensibility was so different from her own, because it was optimistic and upbeat, because it depicted a world she would have loved to have believed in but just couldn’t; I think she needed a dose of that hopeful Roddenberry worldview the way a diabetic needs insulin.)

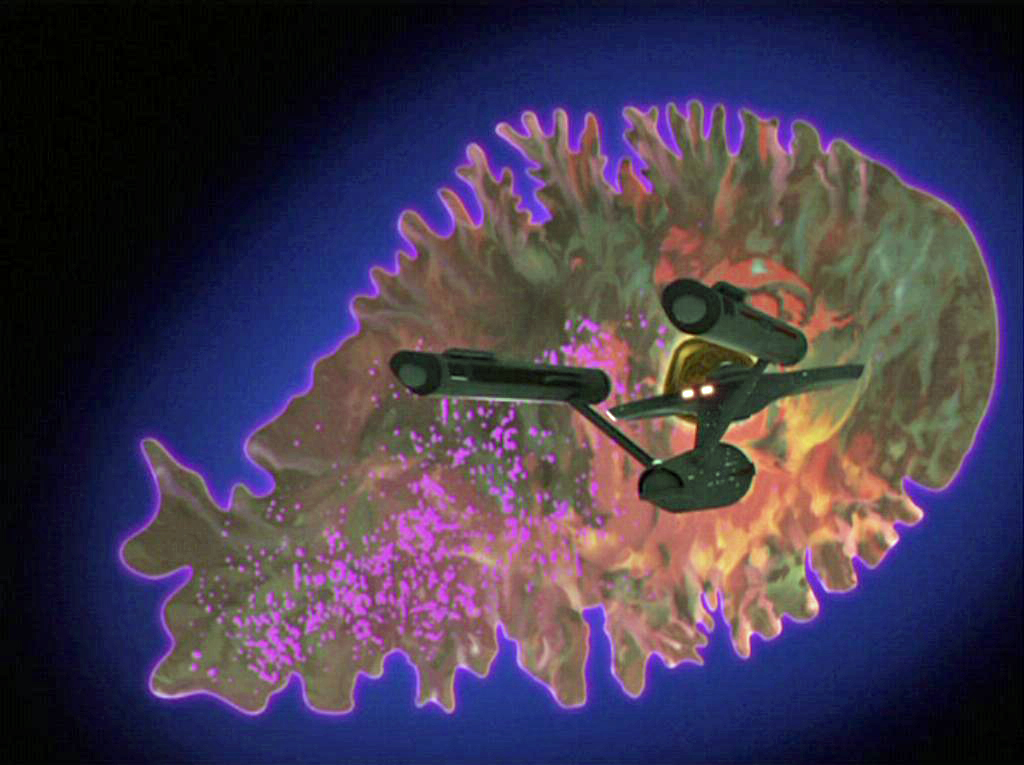

The particulars? On Friday, January 19th, 1968, NBC aired “The Immunity Syndrome,” a Star Trek episode written by Robert Sabaroff, a professional television writer who worked in the medium for thirty years, producing scripts for many different shows. (Twenty years after his script for the original series, he wrote two scripts for Star Trek: The Next Generation.)

In “The Immunity Syndrome,” The Enterprise confronts an enormous one-celled creature that is devouring whole planets and which is (of course!) headed straight for Earth, though I do wonder why, when this sort of situation arose (every other episode, it seemed), Chekov never said, “Kiptin — what’s the big hurry? Considering the astronomical distances inwolved, the (insert name of menace here) won’t arrive in our solar system for another 50,000 years!”

But of course, Starfleet sees the thing as an immediate threat that has to be dealt with right away. While Spock is off in a shuttlecraft investigating the creature, Kirk and McCoy meet in the captain’s cabin and the following dialogue takes place:

Kirk: What is that thing out there, Bones? It’s not intelligent — not yet.

McCoy: It’s a disease, like a virus invading the body of our galaxy.

Kirk: Yes, it is, isn’t it? How many cells does a human body have?

McCoy: Millions.

Kirk: This thing — this cell, this virus. It’s eleven thousand miles long, and it’s one cell. When it grows into millions, we’ll be the virus invading its body!

McCoy: Now isn’t that a thought. Here we are, antibodies of our own galaxy, attacking an invading germ. It would be ironic indeed if that were our sole destiny, wouldn’t it?

Needless to say, James T. Kirk wasn’t ready to embrace that idea (irony wasn’t invented by people who are leading-man handsome, anyway), but I think Alice Sheldon was. I can just see her sitting in her living room in front of her ton-and-a-half Magnavox console television set (those were the days!) and feeling an electric jolt go through her at McCoy’s words, “It would be ironic indeed if that were our sole destiny, wouldn’t it?”

Needless to say, James T. Kirk wasn’t ready to embrace that idea (irony wasn’t invented by people who are leading-man handsome, anyway), but I think Alice Sheldon was. I can just see her sitting in her living room in front of her ton-and-a-half Magnavox console television set (those were the days!) and feeling an electric jolt go through her at McCoy’s words, “It would be ironic indeed if that were our sole destiny, wouldn’t it?”

That cheerless possibility would scare the crap out of Kirk (it scares the crap out of me), but I think it warmed the cockles of Alice Sheldon’s illusion-proof heart. I think she loved the idea; it fit perfectly with her remorseless view of human life and (especially) sexuality.

The grand human drive to the stars, the impulse to “seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before” — what if we didn’t have any choice in the matter? What if we were all just the helpless instruments of a blind, mute biological process? Just specialized cells made to spend ourselves in service of something vaster and more alien than we can ever either perceive or conceive? If everything else about us, everything that we think we are, everything that we think is important, is really nothing in the light of that colossal, overriding imperative? All the brave gold and blue and redshirts of Starfleet “Not even knowing — thinking they were people, thinking they had a chance…”

Ironic? Ironic is hardly the word.

I’ll bet she started reshaping the idea to her own ends during the first commercial, before she was halfway to the fridge.

“I’m a doctor, not a theologian!”

Of course, absent some lost correspondence that probably never existed anyway, my reckless thesis can’t be proven (I can’t even be certain that Alice Sheldon actually saw “The Immunity Syndrome,” though it’s reasonable to assume that she did), and though even the most sympathetic jury might rate my case as no more than plausible, nevertheless, in my heart of hearts I am confident that the Kirk-McCoy exchange in this 1968 Star Trek episode supplied the germ (if I may use the word) for Sheldon’s brilliant 1975 novella. Stranger things have happened, as we may find out if we ever make it to Alpha Centauri.

Now if I can just figure out why Sheldon didn’t turn A Momentary Taste of Being into a full-fledged novel. It would only have taken an opening section on Earth, before the launch of the Centaur, to show us exactly how desperate things had gotten…

I wonder… maybe the answer lies in that 1964 Flipper episode that Robert Sabaroff wrote. I’ll get back to you.

“Ask me about your evolutionary destiny!”

“Ask me about your evolutionary destiny!”

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was A Sure Guide in a Troubled Time: Criswell Predicts

I’m not remotely surprised that Sheldon was a huge Star Trek fan. The Tiptree story “Beam Us Home” (Galaxy 1969, included in Ten Thousand Light Years from Home in 1973) is practically a love letter to the show, dating to very early in Tiptree’s career as a writer.

Bill,

I love that story. As I recall (I read it a long time ago), it’s about a guy with an unhealthy obsession with the show, and yet the closing paragraph captured the lonely fervor of early Star Trek fandom so very, very brilliantly. Now that the show is a cultural phenomenon with literally countless spinoffs and adaptations, it easy to forget that 50 years ago Star Trek fans were very much alone in their passion.

As I wrote in my piece here at Black Gate about “The Last Flight of Dr. Ain” : “The story is wholly about death, extinction — and death and extinction leading to renewal. But a new renewal — no renewal for humanity.

And this theme is truly fundamental to Tiptree. Very often, too, death is linked to sex.”

So, “A Momentary Taste of Being” is perhaps the apotheosis of that!

If the script for “Meet Me at Infinity” existed, you’d think it might have been included in the collection of that title. It sure would be nice to see that.

The Phillips bio gives no indication of the script’s eventual fate, and online sleuthing didn’t reveal anything further; I have to assume that it doesn’t exist anymore, which is a major loss.

I was just messaged by my daughter, a professional librarian and devoted Tiptree fan, that the script for “Meet Me at Infinity” was printed in a 1972 issue of an amateur Star Trek fanzine called Eridani Triad. In my daughter’s words, “it seems like several universities have collections in their archives, but not anything you can just access online.” Samantha is going to see what she can do – stay tuned for further developments!

Holy cats!!!!

The thought that this thing might actually still exist kinda gives me chills.

Although I have to assume that Tiptree scholars have tracked it down many times before. The fact that it’s been ignored tells me that she probably pirated the story for some other work of hers, it’s very minor work, or it was printed only in a very abbreviated form.

Trying not to get my hopes up, I’m saying.

For me personally, both “The Last Flight of Doctor Ain” and “The Screwfly Solution” are even darker stories than this one. It’s remarkable that Her Smoke Rose Up Forever begins with the one-two punch of those incredibly bleak pieces – it’s such an extraordinarily good collection and I strongly echo your recommendation!

Your mention of that collection reminds me that “Her Smoke Rose Up Forever” is for me the most intense and memorable story by Tiptree that I’ve read, both for its appalling premise and for the various narratives that reveal it. I remember reading it first in an anthology called Final Stage where various writers tried each to take a particular type of science fiction story to its outermost limits; Tiptree’s contribution was the single most memorable.

Here’s the fanzine with Tiptree’s Star Trek script.

https://www.fanac.org/fanzines/1_Issue-Maybe_More_to_Come/eridani_triad_3-baron-beetem-brownlee-1972-09.pdf#view=Fit

Yes indeed, my daughter has already sent it to me and I’ll be reading it this evening. Apparently it’s easy to find if you’re not a coot in your sixties. (I do wonder why it wasn’t in the Tiptree Meet Me at Infinity book.)

Thomas,

Almost certainly Tor didn’t have the rights to reprint a Star Trek script, even an unproduced one. To publish it without Paramount’s permission they’d need to have stripped out all the copyrighted names and sanitized the setting.

Thank you, Dale!!

Two things I note immediately:

1) The script is a mere 13 pages, and just scanning the first two, I can see why it likely wasn’t produced. With 26 crew members down with “space shock” from traveling 3 months through empty space, and strange hysteria gripping the bridge crew.

2) But my God, what an incredible Table of Contents, especially for a fanzine. 126 pages of fiction and articles from Hal Clement, Jacqueline Lichtenberg, Ruth Berman, James Tiptree, and many others. Amazing!

I do wonder if what Sheldon sent to the Star Trek producers was formatted as a conventional television script and then she revised it for the fanzine?

All for the grand price of $1.00, no less. How awesome.

Two things:

1– it always amazes me how the same written passage can be read by one person as very bleak and another as being humorous. Different internal voices, I guess.

2– Reckless Thesis was one of my favorite college bnads.

1. Tell me about it. It’s why, every time I start a Cary Grant screwball or a W.C. Fields, my beloved immediately finds some place else to be.

2. Oh, I know! In 1981 I saw them open for Honeymoon Scuba Death.

It is a real shame that HSD didn’t make it past the early 80s. Their bassist did go on to found Boba Fetish in the early ’90s.