Murder as Comedy, Murder as Fantasy: Unfaithfully Yours

Of all the subjects for comedy (romantic entanglements, domestic misunderstandings, military SNAFU’s, workplace kerfluffles, political shenanigans, high school hi-jinx etc.), murder might seem one of the least promising. That’s actually not the case, however, as there have been many comedies of homicide, among them Murder He Says, Arsenic and Old Lace, Kind Hearts and Coronets, Monsieur Verdoux, The Trouble with Harry, Murder by Death, and The Ladykillers (watch the wonderful 1955 Ealing Studios version with Alec Guinness, not the woeful 2004 Cohen Brothers misfire with poor, miscast Tom Hanks), to name just a handful.

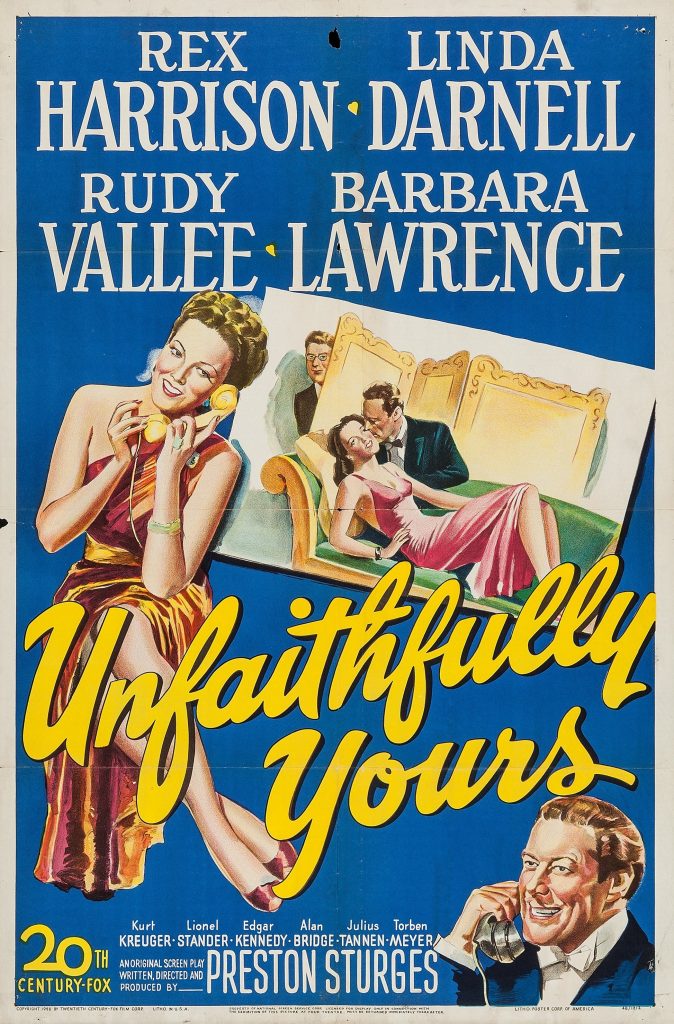

One of the finest — and at the same time, most problematic — examples of this edgy genre is 1948’s Unfaithfully Yours, which came at the end of an extraordinary string of ten films written and directed by Preston Sturges between 1940 and 1948, among them The Great McGinty, The Lady Eve, Sullivan’s Travels, The Palm Beach Story, The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, and Hail the Conquering Hero, a group which can easily commandeer most of an all-time comedy top ten list.

One of the finest — and at the same time, most problematic — examples of this edgy genre is 1948’s Unfaithfully Yours, which came at the end of an extraordinary string of ten films written and directed by Preston Sturges between 1940 and 1948, among them The Great McGinty, The Lady Eve, Sullivan’s Travels, The Palm Beach Story, The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, and Hail the Conquering Hero, a group which can easily commandeer most of an all-time comedy top ten list.

Sturges’ movies are known for their relentless pacing, their acrobatic blend of physical slapstick and literate, rapid-fire dialogue, and the director’s use of a “stock company” of his favorite actors, all gifted at playing people whose fundamental lunacy is exceeded only by their bedrock belief in their own sanity.

The high-wire act performed by Unfaithfully Yours may be the most dazzling and dangerous in the history of humorous homicide, because of the particular brand of murder it deals with: the violence at the heart of the film has its origin in male sexual jealousy and paranoia. In real life that’s no laughing matter, and yet, dark as it is, the film still manages to be a truly uproarious comedy. Picture Othello rewritten by Buster Keaton and you’ll have some idea of the flavor of Unfaithfully Yours.

The story centers on orchestra conductor Sir Alfred de Carter, brittle, brilliant, savagely witty, a virtual Mozart in a world of two-fingered chopsticks players, often showing more than a hint of cruelty as he verbally pummels the slower-witted. Who could he be played by other than Rex Harrison? (Harrison’s Oscar-winning turn as Henry Higgins in My Fair Lady sixteen years later is but a pallid shadow of his gleefully superior, razor-tongued de Carter.)

Sir Alfred is married to a young woman named Daphne, played by Linda Darnell, one of the great beauties of the 1940’s (and a better actress than she often got credit for, a common hazard for great beauties). Their marriage is blissfully happy despite the difference in their ages (Harrison was fifteen years older than Darnell); in the movie’s early scenes they dote on each other and seem to be genuinely, even extravagantly, in love.

All this changes when Sir Alfred is visited by his brother-in-law August (Rudy Vallée). Shortly before, as he was leaving on a concert tour, Sir Alfred had casually asked August to “keep an eye” on Daphne, merely meaning that August and his wife, Daphne’s sister Barbara (Barbara Lawrence) should see that she was not lonely or at loose ends during his absence.

Though all he meant was for August and Barbara to take Daphne out to the movies a time or two, August understood the instructions quite differently; he hired a private detective to follow Daphne and report on her activities while her husband was away. When he proudly presents the results to Sir Alfred, the conductor blows his top, aghast at his brother-in-law’s low-minded stupidity in thinking that his adored Daphne could be up to something — and positively enraged at the idea that he could be so lacking in trust that he would want his wife shadowed.

Though all he meant was for August and Barbara to take Daphne out to the movies a time or two, August understood the instructions quite differently; he hired a private detective to follow Daphne and report on her activities while her husband was away. When he proudly presents the results to Sir Alfred, the conductor blows his top, aghast at his brother-in-law’s low-minded stupidity in thinking that his adored Daphne could be up to something — and positively enraged at the idea that he could be so lacking in trust that he would want his wife shadowed.

Sir Alfred refuses even to dishonor himself by looking at the report; he tears the vile thing to pieces and then flings the shreds into the hallway (the de Carters live in a luxurious residential hotel), slamming the door on the whole unfortunate episode — he thinks. However, the hotel detective finds the pieces, and not knowing how they got there, he glues them together and dutifully returns the reconstructed document to de Carter at the concert hall where the orchestra is rehearsing.

The conductor is even more enraged at this helpful oaf than he was at his idiot brother-in-law, and this time he puts the report in a wastebasket and sets fire to it, intentionally incinerating the document and unintentionally setting the nearby drapes ablaze — along with a good deal of the rest of the room. There’s a lesson there about just leaving well enough alone and not playing with fire, if only Sir Alfred will heed it. He doesn’t.

Still worked-up and worried that more copies of the report may be floating around, Sir Alfred pays a visit to its author, a footpad (“You mean flatfoot, don’t you Sir Alfred?”) named Sweeny, played by the great Edgar Kennedy, a divine comic actor who started in the silent era but is probably best remembered today as the unlucky lemonade vendor who set up business next to Harpo and Chico in Duck Soup.

Storming in to demand all copies of the report from this loathsome individual, de Carter is taken aback to discover that Sweeny is not the Neanderthal that he expected but is instead a passionate music lover and a particular fan of his own conducting; he never misses a concert, in fact. (“The way you handle Handel, Sir Alfred! For me there’s nobody handles Handel like you handle Handel!”) Sweeny misunderstands Sir Alfred’s agitation; he thinks that it’s what’s in the report (which Sir Alfred still hasn’t read) rather than its very existence that’s upsetting his idol.

Assuming that the aggrieved husband already knows the report’s contents, Sweeny inadvertently spills the beans:

You’re just hurt — I can see it. You read that report and naturally it upset you. Ah, we fall for these little dames and try to believe they’re in love with us, but every morning our shaving mirror yells, “They can’t be!” Till one day we find out that youth belongs to youth, like you just done.

When Sweeny sympathetically pats Sir Alfred on the shoulder and the conductor indignantly tells him to take his hand away, the detective continues,

Aw, don’t be sore at me. What have I got to do with it? I suppose it was me that went down to 3406 in the middle of the night wearing only a negligee and stayed for thirty-eight minutes. I suppose that’s the part that bothered you; it usually is.

This stops Sir Alfred in his tracks. And who lives in 3406? The conductor’s personal secretary, Tony (Kurt Kreuger), cheerful, efficient… and young… and handsome… Though Sweeny wisely counsels de Carter to give his wife the benefit of the doubt and forget the whole thing, that’s easier said than done. The poison is in Sir Alfred’s system and by the time he returns home to a worried Daphne (who had no idea where he was) and begins to get ready for the evening’s concert, his manner towards his beloved has changed completely, but she has no clue why.

This stops Sir Alfred in his tracks. And who lives in 3406? The conductor’s personal secretary, Tony (Kurt Kreuger), cheerful, efficient… and young… and handsome… Though Sweeny wisely counsels de Carter to give his wife the benefit of the doubt and forget the whole thing, that’s easier said than done. The poison is in Sir Alfred’s system and by the time he returns home to a worried Daphne (who had no idea where he was) and begins to get ready for the evening’s concert, his manner towards his beloved has changed completely, but she has no clue why.

After snarling and snapping at his bewildered wife until she’s at the point of tears, they arrive at the hall and the program begins. While Daphne, Tony, Barbara, and August watch from their box, Sir Alfred lifts his baton and leads the orchestra in the first piece of the evening, the overture to Rossini’s opera Semiramide. As the music swells, the camera very slowly moves in on Sir Alfred’s face, drawing closer and closer until everything disappears into the utter darkness of his left pupil. The screen is black for a moment, and then we see Sir Alfred and Daphne returning to their apartment after the concert.

They’re not home many minutes before Sir Alfred says that he needs to meet with his manager to do some work preparing for his next tour and suggests that Daphne go out dancing. Who with? Why not Tony? After briefly feigning indifference to the idea, Daphne coyly agrees. (Her manner throughout makes it clear that despite her pro-forma protests, she would like nothing better than an intimate evening with her husband’s secretary.) She goes into the bedroom to get ready, changing into a more alluring dress — at Sir Alfred’s suggestion. (“Now go and call Tony and tell him to pick you up in fifteen minutes — exactly. And then put on the purple one, with the plumes at the hips”.)

While his wife is in the bedroom preparing for the rest of her evening, Sir Alfred leaps into action, initiating a diabolical Rube-Goldbergesque plan that will do away with the faithless strumpet that he’s married to and dispose of two-faced Tony at the same time.

Rushing to a closet, he takes a bulky case down from the top shelf. It turns out to contain a sort of home recording studio, and hauling it into the bathroom, he quickly records a bit of dialogue that makes it sound like Tony is attacking Daphne. (He uses the controls to alter the pitch of his voice to make it sound like his wife’s, as he shouts, “Stop, Tony, stop! Murder! Police! Murder!!“) The whole procedure takes about two minutes, during which time Daphne is on the phone, shamelessly flirting with Tony.

Setting the resulting record aside for later (1948, remember — vinyl!) Sir Alfred puts the recording equipment away. Then he gets his straight razor, goes into the bedroom, flings Daphne on the bed, and savagely cuts her throat. (It later comes out that she has been virtually decapitated.) It’s a truly shocking scene, with the fatal moment seen from Daphne’s point of view, the screen filled with Sir Alfred’s maniacally grinning, demonically gleeful face.

Setting the resulting record aside for later (1948, remember — vinyl!) Sir Alfred puts the recording equipment away. Then he gets his straight razor, goes into the bedroom, flings Daphne on the bed, and savagely cuts her throat. (It later comes out that she has been virtually decapitated.) It’s a truly shocking scene, with the fatal moment seen from Daphne’s point of view, the screen filled with Sir Alfred’s maniacally grinning, demonically gleeful face.

The deed done, Sir Alfred cleans the razor and then sets the rest of his infernal machine in motion. When Tony arrives (on time to the second), Sir Alfred greets him the way the cat greeted the canary and asks him to take a look at his razor and make sure that it’s sharp (he had Tony take it down to the barbershop that morning for sharpening), and once his secretary has his fingerprints on the blade, Sir Alfred goes into the bedroom, supposedly to tell his wife that her date has arrived (actually to re-smear the razor with her blood). He then cues the record to begin playing at exactly the right moment and walks out of the apartment, telling Tony that Daphne will be out soon and bidding him good night.

Sir Alfred then goes downstairs to the front desk and asks the clerk to call his apartment and see if his manager is there. At that precise instant the recording starts and Tony hears screams coming from the next room; he bursts through the door, upsetting an end table on which Sir Alfred had placed the telephone, knocking it off the hook. As his stunned secretary is goggling at Daphne’s body, Sir Alfred and the clerk (and the house detective) are downstairs hearing “Daphne’s” agonized shrieks of “Tony!! NO!! Murder!” By the time the police arrive, the phonograph has dropped the next record and is playing something else, and Sir Alfred unobtrusively disposes of the faked recording.

The plan is brilliantly conceived and executed (never mind that Lieutenant Columbo would have seen through it in five minutes), and the case is open and shut. The sequence jumps forward to end in a courtroom with a judge sentencing a bleating Tony to death for the murder of Lady de Carter as Sir Alfred roars with laughter. And then…

The camera slowly pulls back out of the conductor’s eye and we’re in the concert hall again, listening to the end of the Semiramide Overture — which, we now realize, has never stopped playing all through the murder and courtroom scenes. The whole appalling thing was Sir Alfred’s twisted fantasy. It could be nothing else, with its split-second timing working perfectly and a vicious murder committed without the attacker getting a drop of blood on himself (someone who kills with a straight razor while wearing a tuxedo is unlikely to emerge absolutely spotless) — to say nothing of the fact that the smirking, lewd, underhanded Daphne of Sir Alfred’s tainted dream is completely unlike the loyal, forthright, honestly adoring woman that we have seen up to this point.

The camera slowly pulls back out of the conductor’s eye and we’re in the concert hall again, listening to the end of the Semiramide Overture — which, we now realize, has never stopped playing all through the murder and courtroom scenes. The whole appalling thing was Sir Alfred’s twisted fantasy. It could be nothing else, with its split-second timing working perfectly and a vicious murder committed without the attacker getting a drop of blood on himself (someone who kills with a straight razor while wearing a tuxedo is unlikely to emerge absolutely spotless) — to say nothing of the fact that the smirking, lewd, underhanded Daphne of Sir Alfred’s tainted dream is completely unlike the loyal, forthright, honestly adoring woman that we have seen up to this point.

One wonders how many people in 1948 didn’t realize until the return to the concert that the killing hadn’t really happened. Quite a few, I would wager, and even now when viewers are much more accustomed to sophisticated cinematic tricks, the movie has been known to fool the inadequately attentive.

The next two concert pieces (the prelude to Wagner’s Tannhäuser and Tchaikovsky’s symphonic poem Franchesca da Rimini) begin and end in the same way, taking us into Sir Alfred’s fevered mind and through two more fantasies, one in which he sardonically commits suicide in front of the terrified adulterers, and another in which he nobly forgives Daphne, taking all the blame on himself as he gives her her freedom — and a check for one hundred thousand dollars — while telling his weeping, remorseful wife that of course she was drawn to Tony, because “Youth is for youth, and beauty is for beauty.” Now where have we heard that before?

After the concert, Sir Alfred rushes out of the hall without even taking a bow, intent on getting home well ahead of his wife in order to act out his homicidal fantasy. Transferring his plan from the world of daydreams to the realm of perverse material objects isn’t so easy, however, as the entire physical universe now conspires to make an utter fool of him. The next fifteen minutes, as Sir Alfred tries vainly to replicate his vision, comprise one of the greatest sequences of sustained slapstick in the history of film. Its closest analogue may be the industrial feeding-machine scene from Chaplin’s Modern Times, another film that has something to say about the difference between our reach and our grasp.

Daphne, Tony, Barbara, and August

Daphne, Tony, Barbara, and August

Sir Alfred can’t find a pair of gloves that fit (all careful murderers wear gloves) — they all seem to have too many or too few fingers; the recording device isn’t in the closet where he thought it was (and the chair that he’s standing on to reach the top shelf keeps tipping over); when he moves to the next closet he has to stand on his desk, and he steps on his glasses and keeps getting his foot tangled in the phone cord; when he tries to open the closet the knob comes off; he remembers that the case is in another room entirely and when he charges in there he doesn’t bother to turn on the light and knocks over a chair, a lamp, a table and the telephone, breaking the table and the lamp; when he drags a cane-bottomed chair to the closet so he can reach the shelf, his foot goes through the seat; when he finds the case, a dozen loose light-bulbs are in front of it and they all fall off the shelf and explode on the floor; when, with a mighty tug, he pulls the case out of the closet, it flies across the room and shatters a sliding glass door on its way out to the balcony; when he retrieves the case and opens it, it turns out not to be the recording device but a home casino, and when he disgustedly tries to carry it back to the closet the bottom falls out and litters the room with dice, cards, roulette balls and poker chips.

And all this is only the prelude to Sir Alfred’s real hell. When he eventually finds the recording set (according to the instruction sheet, “The first thing to remember about the Simplicitas Home Recording Unit is that it is so simple it operates itself!“) it proves to be nothing less than a torture device, as anyone who read the directions would know: “To change from 78 RPM to 33 1/3 RPM merely lift the Cam Dog A-1-a-3 (see simplified diagram on page 6) and holding it between the thumb and index finger of the left hand push the sliding spindle shaft bell rotator (B-1-a) in and over.” Despite all his exertions, the damned thing will not do what he wants it to do; after an eternity of fruitless effort, when he finally gets it to record something, instead of changing his voice to a Daphne-like timbre, it slows and thickens it until it is the aural equivalent of cold molasses, as if Sir Alfred had washed down a fistful of quaaludes with a fifth of Old Crow. People have been known to literally be unable to get off the floor after watching this scene, even to change their soiled underwear.

And all this is only the prelude to Sir Alfred’s real hell. When he eventually finds the recording set (according to the instruction sheet, “The first thing to remember about the Simplicitas Home Recording Unit is that it is so simple it operates itself!“) it proves to be nothing less than a torture device, as anyone who read the directions would know: “To change from 78 RPM to 33 1/3 RPM merely lift the Cam Dog A-1-a-3 (see simplified diagram on page 6) and holding it between the thumb and index finger of the left hand push the sliding spindle shaft bell rotator (B-1-a) in and over.” Despite all his exertions, the damned thing will not do what he wants it to do; after an eternity of fruitless effort, when he finally gets it to record something, instead of changing his voice to a Daphne-like timbre, it slows and thickens it until it is the aural equivalent of cold molasses, as if Sir Alfred had washed down a fistful of quaaludes with a fifth of Old Crow. People have been known to literally be unable to get off the floor after watching this scene, even to change their soiled underwear.

In the midst of this, Daphne and Tony arrive home. Sir Alfred’s explanation for the chaos? “I was making an experiment. People do, you know; without them there would be very little progress in this world!” He then peremptorily — and rudely — dismisses Tony. Once he’s gone, Sir Alfred, unwilling to give up the ship just yet, asks Daphne whether she wouldn’t like to go out dancing with Tony. Daphne looks at him as if he’s lost his mind. “With Tony? Have you ever seen Tony dance? I saw him once with Barbara and he gets up on his toes like a rooster and he pushes you over sideways and then he shoves your head back till you think it’s going to drop off — why, compared with him you look like Arthur Murray!” So… no murder tonight. Plan B?

Going to the desk, Sir Alfred takes out his checkbook but is unable to make his bewildered wife a generous settlement because all the ink shoots out of his fountain pen and ruins all the checks. After a night like this, what’s left but suicide? Pulling his revolver out of another drawer, he first finds the gun impossibly tangled in a cord of some kind, and once untangled, he discovers that it is empty and that the bullets are nowhere to be found. Checkmate.

While she’s vainly trying to placate her foul-tempered husband (still without knowing the source of his rage) Daphne mentions something that happened one night when Sir Alfred was away on his last tour. She received a call from August asking if Barbara was there with her, which is where Barbara had told him she would be — only Barbara wasn’t there. “I told him that she had been here with me and had just left and then I threw on a negligee and I hurried down there just in case.” Hurried down where? To 3406, Tony’s room, where she suspected her kid sister might be. The door was open, so Daphne went in prepared to chew Barbara out, only to discover that there was no one there… but when she turned to go out, she saw a “great big old jerk” skulking in the hall, and not wanting to be seen late at night in a negligee exiting the room of a man not her husband, she waited inside until Sweeny — because that’s who it was, of course — left. How long did she have to wait? An ecstatic Sir Alfred supplies the answer himself — “For thirty-eight minutes! He kept you there himself!”

While she’s vainly trying to placate her foul-tempered husband (still without knowing the source of his rage) Daphne mentions something that happened one night when Sir Alfred was away on his last tour. She received a call from August asking if Barbara was there with her, which is where Barbara had told him she would be — only Barbara wasn’t there. “I told him that she had been here with me and had just left and then I threw on a negligee and I hurried down there just in case.” Hurried down where? To 3406, Tony’s room, where she suspected her kid sister might be. The door was open, so Daphne went in prepared to chew Barbara out, only to discover that there was no one there… but when she turned to go out, she saw a “great big old jerk” skulking in the hall, and not wanting to be seen late at night in a negligee exiting the room of a man not her husband, she waited inside until Sweeny — because that’s who it was, of course — left. How long did she have to wait? An ecstatic Sir Alfred supplies the answer himself — “For thirty-eight minutes! He kept you there himself!”

And so the jealous nightmare that was sparked by accident, by August’s idiocy and Sweeny’s inadvertent disclosure, is dissipated in the same accidental way.

The film ends with an outpouring of the unashamedly romantic feeling that was another one of Preston Sturges’ trademarks. At these welcome revelations, Sir Alfred seizes his wife, not with rage or malice, but in a joyous rapture. After telling Daphne to get ready for a night on the town, he declares,

I happen to want to celebrate! I want to be seen in your exquisite company. I want the whole world to know that I am the most fortunate of men in the possession of the most magnificent of wives. I want to swim in champagne and paint the whole town not only red, but red, white, and blue! I want everybody to see how much I adore you, always have adored you, revere you, and… and trust you. Also, how much I hope you have of warmth for me.

When the baffled but happy Daphne asks, “What was the matter with you tonight, Alfred?” he replies, “Something so vulgar, so utterly contemptible and unworthy of a love like yours, that I beg of you to never make me tell you.” And after receiving Daphne’s assurances of understanding and forgiveness, he looks at his wife with adoring eyes and as the music swells, says, with deep emotion, “A thousand poets dreamed a thousand years, and you were born.”

Unfaithfully Yours is an audacious and brilliant movie, and yet it is impossible not to feel that Sir Alfred’s violent fantasies seem much too potent (and too quickly summoned) to be so easily dismissed; there’s something fundamental here that’s not being dealt with. Whether the problem is a character flaw or a cultural pathology or some combination of the two, it’s never resolved because it’s never really addressed. 1948 audiences clearly felt that there was something lacking (did they feel cheated by the film’s “only a dream” aspect — or was the story just too disturbing?), because Unfaithfully Yours was not a box-office success and its failure marked the end of Sturges’ career as a major director.

Almost as problematic as Sir Alfred’s warped fantasies are the very dark things the movie implies about the wellsprings of art and creativity — everyone, even Sweeny (Sir Alfred gives him a ticket before he storms out of his office) seems to think that the conductor has given the greatest concert of his life, unaware of the morbid thoughts that are fueling his passionate performance. (Has anyone ever theorized that Gustav Mahler was Jack the Ripper? Maybe they should have.)

And yet, Unfaithfully Yours — perhaps now more than ever — has something valuable (and deeply subversive) to say about how our self-flattering fantasies of frictionless control can come to grief when they collide with a stubbornly intractable material world that we are less masters of than arrogant, overreaching rebels against. (The Greeks had a word for it: hubris.) In any case, anyone contemplating a major project, whether it’s remodeling a kitchen, subduing a Middle-Eastern country, creating a self-aware AI to solve all human problems, or relocating homo sapiens to Mars, (all projects that have been and will be sold to us as so simple they complete themselves!) would do well to give Unfaithfully Yours a thoughtful viewing.

I suspect (that ugly word again!) that Unfaithfully Yours has the flaws that it does because those deficiencies are simply inherent in the movie Preston Sturges wanted to make — the only movie he could make. If that’s so, I have no complaints, and if I could go to the theater tonight and see a comedy with half the speed, energy, wit, inventiveness, surprise, danger, and (finally) depth of feeling of Unfaithfully Yours, I would consider my time and money to have been very well spent indeed.

I suspect (that ugly word again!) that Unfaithfully Yours has the flaws that it does because those deficiencies are simply inherent in the movie Preston Sturges wanted to make — the only movie he could make. If that’s so, I have no complaints, and if I could go to the theater tonight and see a comedy with half the speed, energy, wit, inventiveness, surprise, danger, and (finally) depth of feeling of Unfaithfully Yours, I would consider my time and money to have been very well spent indeed.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was Cruel Yule: The Star Wars Holiday Special and Other Abominations

Thanks … I have been very slowly making my way through the Sturges oeuvre, and this is one I really didn’t know about.

Could the name Sweeny be a sly allusion to Sweeney Todd? (I mean, with the razor as a murder weapon and all!)

Oh, and I’m in complete agreement about The Ladykillers. That might be the only Coen Brothers film I don’t like.

I hadn’t thought of that, Rich. It might be – with the caveat that Sweeny is the sanest, most humane person in the movie.

Always happy to see Sturges get some attention. The man and his work is long overdue for another round of appreciation. This is the only one on the list I haven’t seen so I’ll have to track it down. Thanks for the nudge.

This is a great, very thoughtful review-essay of a flawed masterpiece. I saw it for the first time a few years ago, just after finding out what a rat-bastard Harrison was in real life. (The unfailingly courteous Patrick Macnee called him “one of the top five unpleasant men you’ve ever met”.) That lent an extra layer of darkness to the dark elements of this comedy.

Thanks for the praise, James, and Harrison was indeed a nasty piece of work; a lot of people believe that he drove Carole Landis to suicide – in 1948, the year of Unfaithfully Yours.

Another odd coincidence – that same year, Barbara Lawrence was attacked in a darkened movie theater, receiving a serious stab wound. The attacker was never found.