A World Built on Atrocity: Damon Knight’s “Down There”

|

|

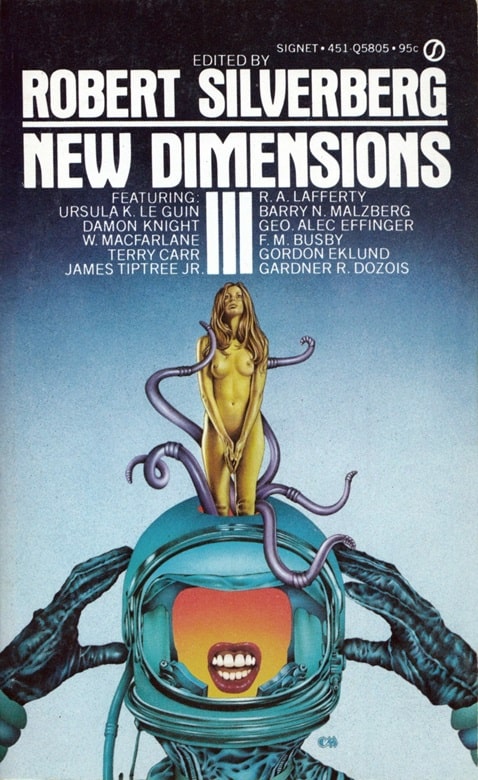

New Dimensions III, edited by Robert Silverberg

(Signet/New American Library, February 1974). Cover by Charles Moll

One of the writers who strongly influenced me when I was learning to write fiction was Damon Knight.

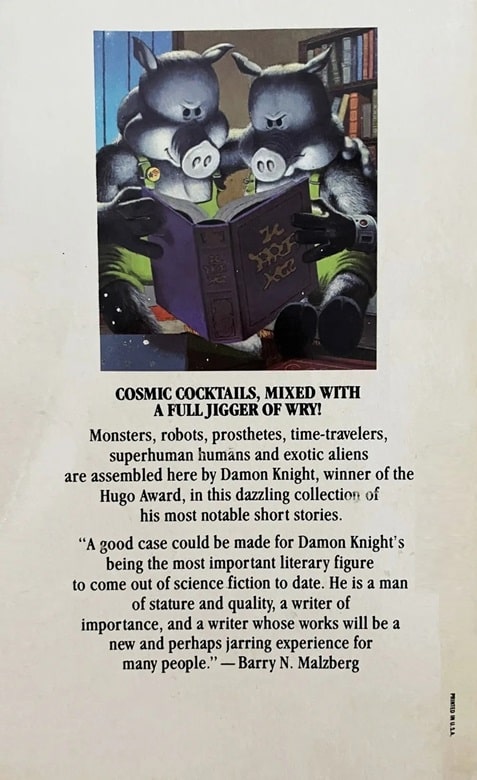

Although he founded the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, co-founded the Milford Writers’ Workshop, made the Clarion Writers’ Workshop the force that it is in the development of speculative fiction, edited the influential anthology series Orbit, and wrote one of the first significant critical works on science fiction, In Search of Wonder, his fiction is little remembered today.

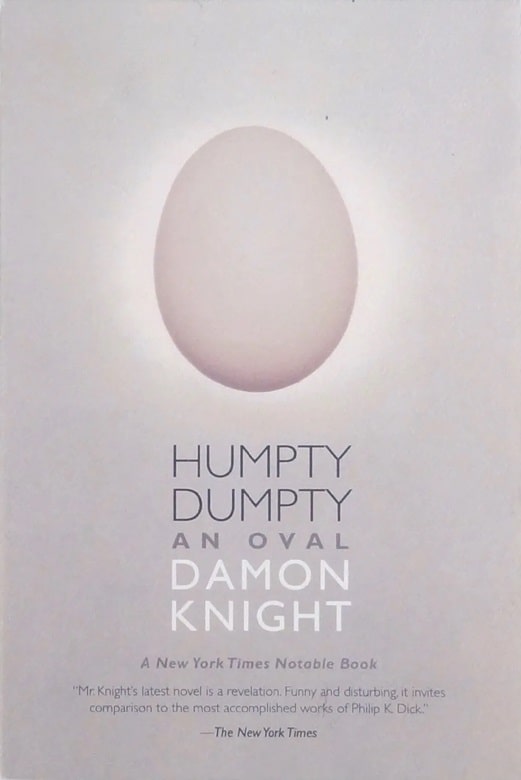

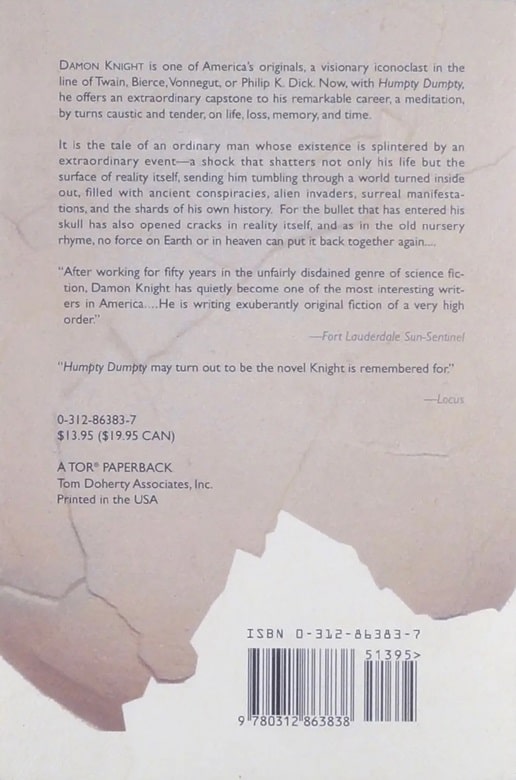

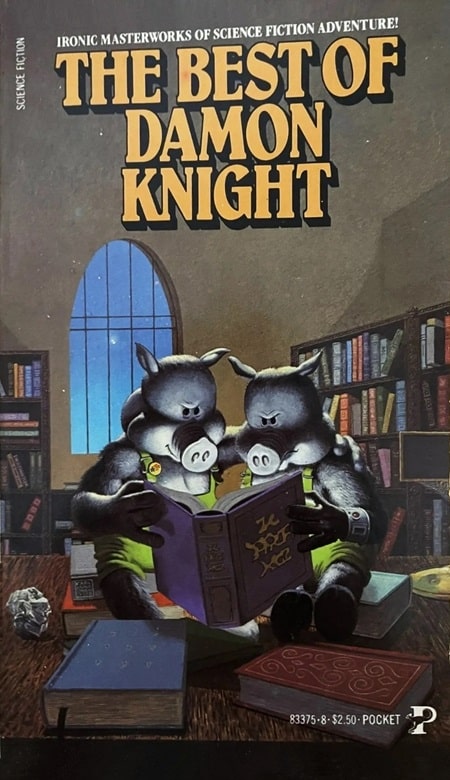

Knight was a brilliant writer of short stories. He also wrote some damn good novels; his last one Humpty Dumpty, An Oval, published in 1996, is sui generis. But I want to talk about one of his most obscure stories, “Down There,” which appeared originally in the anthology New Dimensions 3 in 1973. It’s also available in The Best of Damon Knight.

[Click the images for larger versions.]

In Search of Wonder (Advent: Publishers, 1956). Cover by Jon Stopa

“Down There” takes place in a single day (April 11, 2012), in a New York City of the future. The protagonist, Bob Norbert, is a writer; the story opens with him going to work in his studio and follows him as he writes a short story in collaboration with a computer.

The computer writing scene is remarkably prescient. Writing fifty years before ChatGPT, Knight describes Norbert sitting before his screen and selecting a theme from a menu (“COME TO REALIZE, VICTORY OVER RIVAL, ADJUSTMENT WITH GROUP”) and a setting (“NEW YORK, PARIS, LONDON, SAN FRANCISCO, DALLAS, BOSTON, DISNEYWORLD, ANTWERP, OCEAN TOWERS”). Norbert begins:

Sunlight, he wrote, and the screen added promptly fell from the ceiling as — and here Norbert’s plunging finger stopped it; the words remained frozen on the screen while he frowned and sucked on his pipe, his gurgling briar. Fell wouldn’t do, to begin with, sunlight didn’t fall like a flowerpot. Streamed? Well, perhaps — No, wait, he had it. He touched the word with the light pen, then tapped out spilled. Good-oh. Now the next part was too abrupt; there was your computer for you every time, hopeless when it came to expanding on an idea; and he touched the space before ceiling and wrote huge panes of the.

The text now read:

Sunlight spilled from the huge panes of the ceiling as

Norbert punched “Start” again and watched the sentence grow: … as Inez Trevelyan crossed the plaza among the hurrying throngs.

With the help of what we today would call an AI, Norbert finishes his story in a few hours. When he has a factual question he looks it up in what we today would call “online.” Through the computer he gets messages from his editor and consults his dwindling bank account to check his weekly earnings.

This whole section is prescient, and amusing as we come to realize Norbert is a hack. His bylines read “by IBM and R.A. Norbert.” The story he’s writing is a cliched tale of a married woman coming to realize that her marriage is not working, complete with her fleeing her home to a romanticized County Clare, Ireland, with its “fields of daisies,” and concluding with her heartfelt farewell to her (two) husbands:

‘You must go on to the wonderful things and far places that are waiting for you . . . but I’ — and her eyes were suddenly misty as the dawn over Kilarney — ‘I know that my yellow daisies are here.’

Well satisfied with his work, Norbert then calls up a work-in-progress, his “literary” story, a piece of faux-Finnegans Wake linguistic noodling, and grouses about how he’ll never be able to sell it to the highbrow magazine Ficciones, “although it was exactly like the stuff they printed all the time; if you weren’t in their clique, you didn’t have a chance.” How many sf writers have felt this way about The New Yorker?

|

|

Humpty Dumpty: An Oval (Tor, September 1996). Cover by Shelley Eshkar

Leaving his studio Norbert stops in the bank to get some cash; the teller there is curious as to why he needs cash when everybody uses cards instead: in this future using cash has the whiff of the illicit. He runs into Art and Ellen Whitney, friends who invite him to join them in a double date with their attractive friend Phyllis. Bob begs off, claiming it’s his sister’s birthday.

In the end we learn what Norbert needs the cash for: that evening he goes uptown to a run-down neighborhood on 169th Street, in what would in 1973 have been Harlem, enters a sordid tenement, and hires a prostitute. End of story.

The ending may seem like an abrupt non-sequitur. What is it really about?

It’s about the return of the repressed, and about how this ordinary world is built on a foundation of atrocity.

To see this you must pay careful attention to the everyday details Knight plants that reveal this world. Some of them seem like the standard furniture of science fiction: There is a dome over the city and elevated monorail trains. Some women have smooth faces, “Gordonized” to remove wrinkles. A vending machine dispenses magazines that carry ads for “Vaginal Gloss” and an article titled “Q Fever — The Unknown Killer” (COVID-19, anyone?).

But the magazine also contains an article titled “Race Suicide — Is It Happening to Us?” Elsewhere Norbert encounters a security guard who is “a crippled veteran of the Race War.”

These details point toward the subtext at the heart of this story. As Norbert walks the run-down streets of Harlem there are no Black people; instead the neighborhood is full of whites, “’billies and their girls lounging and spitting,” “good old boys” eating “pork and mustard greens” and drinking at a bar named the “Peachtree.” The man who pimps the prostitutes is a blue-eyed white man from the South. Harlem has been taken over by white southerners.

|

|

The Best of Damon Knight , containing “Down There”

(Pocket Books, July 1980). Cover by Carl Lundgren

We’re in Norbert’s viewpoint through all of this: he has clear distaste for good old boys and hillbillies, feeling he is a class above them, but he’s willing to deal with them to get what he wants. The illicit sex Norbert seeks out in what used to be Harlem is with a woman who is “olive-skinned, almost Latin-looking; the folds of her heavy face were so dark that they seemed grimy.” Under black eyebrows she looks at him with eyes that are “evil, weary and compassionate.”

This is the shameful thrill that lies “down there” beneath Norbert’s pallid life writing white-bread romantic claptrap for popular magazines: sex with a Black woman. And why is this such an illicit desire, difficult to indulge? Because this world is built on another repressed reality: the corpses of African Americans exterminated in a race war. There are no Black people in everyday American life, at least in New York City. The only such people left are consigned to the possession of immigrant Southerners who offer them for use by twisted, self-deluding racists like Bob Norbert. “Down There” is revealed in the end to be a horror story about a future American racial holocaust.

Damon Knight was one of the writers whose work taught me that you don’t have to spell it out or resort to lectures for your story to make a point. From him I learned that the protagonist is not always the hero, that in fact putting some distance between the character’s opinions and the author’s is fundamental to good fiction. That characters are moved by unconscious motives as much as by conscious ones. That science fiction can be political without being preachy. That a powerful emotional effect can come without violence or melodrama. That a story element such as the physical setting can serve more purposes than simply stage dressing. That leaving the reader with something they have to figure out is a way to have the story linger in their mind. Knight was not the only sf writer whose stories exhibited these traits, but he was among the finest.

I only met Damon Knight once in my career, briefly, at a science fiction convention. Years later, only weeks before he died, we exchanged some emails, in which I am glad to say I expressed to him how much I valued his work and how much it had taught me. His fiction deserves to be read and remembered.

John Kessel’s last article for Black Gate was a look at The Confidence-Man by Herman Melville. He is the author of the novels Good News From Outer Space (1989), Corrupting Dr. Nice (1997), The Moon and the Other (2017), and Pride and Prometheus (2018), plus Freedom Beach (1985) written with his friend James Patrick Kelly. Kessel won a Nebula Award for his 1982 novella “Another Orphan,” in which the narrator finds himself inside Melville’s Moby-Dick, and a second Nebula for the novelette version of “Pride and Prometheus” (2008). His website is johnjosephkessel.wixsite.com.

My (sad) guess would be that Mr. Knight will best be remembered for his short-short sf horror story, “To Serve Man”, mainly due to the Twilight Zone adaptation. I picked up an original edition of his first novel, hell’s pavement, and I should (carefully) read it.

Eugene,

Without question that’s his most famous story, though when I think of Damon Knight these days I remember him mostly as an editor, and an astute and unsparing critic of science fiction.

That probably does him a disservice. Knight’s short fiction was extraordinary. I read “I See You” in Terry Carr’s Best Science Fiction of the Year #6 in 1977, and it has stayed with me for the past 47 years.