A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens

If I could work my will,” said Scrooge indignantly, “every idiot who goes about with ‘Merry Christmas’ on his lips, should be boiled with his own pudding, and buried with a stake of holly through his heart. He should!”

Ebenezer Scrooge

A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas, published first in 1843, is nearly two hundred years old, and nothing remains to be said about it, it would seem. Charles Dickens’s fairy tale has become one of the great secular staples of the Christmas season. It’s been filmed many times; both wonderfully as in the Alastair Sim 1951 and George C. Scott 1984 versions and less wonderfully in the Reginald Owen 1938 film and the 2010 Jim Carrey motion capture monstrosity. Furthermore, there have been animated adaptations, musicals, and comics. It’s an isolated person, I suspect, who doesn’t know at least the basic setup: the uplifting story of a cold-hearted miser who turns to the good after the visitation of a trio of ghosts representing the spirit of the season. All I can do is comment on the bits that stood out for me while liberally quoting from this mordantly funny novel and Gothic fantasy of redemption.

The story is told by an omniscient narrator who intrudes on the story constantly, digresses from the narrative, and questions the reader at every turn. The opening words of A Christmas Carol, or at least a fair gloss on them, are well-known, particularly the seventh sentence: “Old Marley was a dead as a door-nail.” It’s a blunt matter-of-fact statement that lets the reader know where things stand. The narrator, though, immediately continues with something else.

“Mind! I don’t mean to say that I know, of my own knowledge, what there is particularly dead about a door-nail. I might have been inclined, myself, to regard a coffin-nail as the deadest piece of ironmongery in the trade. But the wisdom of our ancestors is in the simile; and my unhallowed hands shall not disturb it, or the Country’s done for. You will therefore permit me to repeat, emphatically, that Marley was as dead as a door-nail.”

It’s been ages since I’ve read A Christmas Carol and I admit I was unprepared for a digression on the validity of an idiom followed by the instant submission to tradition. It’s a perfect introduction to the tale-teller’s humorously discursive style. Most of the humor, though, comes from Dickens’s perfectly tuned descriptions and turns of phrase.

Still recovering from his journey through his younger days with the Ghost of Christmas Past, Scrooge, nonetheless prepares himself for the arrival of the second ghost. While it’s a long-winded way of saying Scrooge is ready for anything, it’s also a nice jab at a logical man’s vulnerability in the face of the supernatural.

Still recovering from his journey through his younger days with the Ghost of Christmas Past, Scrooge, nonetheless prepares himself for the arrival of the second ghost. While it’s a long-winded way of saying Scrooge is ready for anything, it’s also a nice jab at a logical man’s vulnerability in the face of the supernatural.

Awaking in the middle of a prodigiously tough snore, and sitting up in bed to get his thoughts together, Scrooge had no occasion to be told that the bell was again upon the stroke of One. He felt that he was restored to consciousness in the right nick of time, for the especial purpose of holding a conference with the second messenger despatched to him through Jacob Marley’s intervention. But, finding that he turned uncomfortably cold when he began to wonder which of his curtains this new spectre would draw back, he put them every one aside with his own hands, and lying down again, established a sharp look-out all round the bed. For, he wished to challenge the Spirit on the moment of its appearance, and did not wish to be taken by surprise, and made nervous.

Gentlemen of the free-and-easy sort, who plume themselves on being acquainted with a move or two, and being usually equal to the time-of-day, express the wide range of their capacity for adventure by observing that they are good for anything from pitch-and-toss to manslaughter; between which opposite extremes, no doubt, there lies a tolerably wide and comprehensive range of subjects. Without venturing for Scrooge quite as hardily as this, I don’t mind calling on you to believe that he was ready for a good broad field of strange appearances, and that nothing between a baby and rhinoceros would have astonished him very much.

Now, being prepared for almost anything, he was not by any means prepared for nothing

And, of course, there are all Scrooge’s sarcastic bon mots in the face of things he dislikes or is frightened of. One of the most well-known arises from his conversation with his late partner Jacob Marley’s spirit, though it’s more inspired by fear than ill-temper the way it’s presented in most adaptations.

“Because,” said Scrooge, “a little thing affects them. A slight disorder of the stomach makes them cheats. You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of an underdone potato. There’s more of gravy than of grave about you, whatever you are!”

Scrooge was not much in the habit of cracking jokes, nor did he feel, in his heart, by any means waggish then. The truth is, that he tried to be smart, as a means of distracting his own attention, and keeping down his terror; for the spectre’s voice disturbed the very marrow in his bones.

All I remembered, aside from a few classic lines, were the basic bones of the story; the assorted ghosts and the scenes they present for Scrooge. I’d forgotten how strange and unsettling a story Dickens wove in A Christmas Carol. One of the most fantastical elements is the appearance of the Ghost of Christmas Past. The great, almost overwhelming Ghost of Christmas Present insisting that Scrooge get to know him better and the spectral Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come dressed in black robes are both well-known and closely hew to Dickens’s description in the various movies. It’s the Ghost of Christmas Past, though who’s depicted in numerous ways. The reason for this, I suspect, derives from Dickens’s unearthly description.

All I remembered, aside from a few classic lines, were the basic bones of the story; the assorted ghosts and the scenes they present for Scrooge. I’d forgotten how strange and unsettling a story Dickens wove in A Christmas Carol. One of the most fantastical elements is the appearance of the Ghost of Christmas Past. The great, almost overwhelming Ghost of Christmas Present insisting that Scrooge get to know him better and the spectral Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come dressed in black robes are both well-known and closely hew to Dickens’s description in the various movies. It’s the Ghost of Christmas Past, though who’s depicted in numerous ways. The reason for this, I suspect, derives from Dickens’s unearthly description.

It was a strange figure—like a child: yet not so like a child as like an old man, viewed through some supernatural medium, which gave him the appearance of having receded from the view, and being diminished to a child’s proportions. Its hair, which hung about its neck and down its back, was white as if with age; and yet the face had not a wrinkle in it, and the tenderest bloom was on the skin. The arms were very long and muscular; the hands the same, as if its hold were of uncommon strength. Its legs and feet, most delicately formed, were, like those upper members, bare. It wore a tunic of the purest white; and round its waist was bound a lustrous belt, the sheen of which was beautiful. It held a branch of fresh green holly in its hand; and, in singular contradiction of that wintry emblem, had its dress trimmed with summer flowers. But the strangest thing about it was, that from the crown of its head there sprung a bright clear jet of light, by which all this was visible; and which was doubtless the occasion of its using, in its duller moments, a great extinguisher for a cap, which it now held under its arm.

Even this, though, when Scrooge looked at it with increasing steadiness, was not its strangest quality. For as its belt sparkled and glittered now in one part and now in another, and what was light one instant, at another time was dark, so the figure itself fluctuated in its distinctness: being now a thing with one arm, now with one leg, now with twenty legs, now a pair of legs without a head, now a head without a body: of which dissolving parts, no outline would be visible in the dense gloom wherein they melted away. And in the very wonder of this, it would be itself again; distinct and clear as ever.

The depiction of Marley’s advent is a magnificently spooky passage worthy of MR James that ends with Scrooge still managing to find some humor his situation.

After several turns, he sat down again. As he threw his head back in the chair, his glance happened to rest upon a bell, a disused bell, that hung in the room, and communicated for some purpose now forgotten with a chamber in the highest story of the building. It was with great astonishment, and with a strange, inexplicable dread, that as he looked, he saw this bell begin to swing. It swung so softly in the outset that it scarcely made a sound; but soon it rang out loudly, and so did every bell in the house.

This might have lasted half a minute, or a minute, but it seemed an hour. The bells ceased as they had begun, together. They were succeeded by a clanking noise, deep down below; as if some person were dragging a heavy chain over the casks in the wine-merchant’s cellar. Scrooge then remembered to have heard that ghosts in haunted houses were described as dragging chains.

The cellar-door flew open with a booming sound, and then he heard the noise much louder, on the floors below; then coming up the stairs; then coming straight towards his door.“It’s humbug still!” said Scrooge. “I won’t believe it.”

His colour changed though, when, without a pause, it came on through the heavy door, and passed into the room before his eyes. Upon its coming in, the dying flame leaped up, as though it cried, “I know him; Marley’s Ghost!” and fell again.

The same face: the very same. Marley in his pigtail, usual waistcoat, tights and boots; the tassels on the latter bristling, like his pigtail, and his coat-skirts, and the hair upon his head. The chain he drew was clasped about his middle. It was long, and wound about him like a tail; and it was made (for Scrooge observed it closely) of cash-boxes, keys, padlocks, ledgers, deeds, and heavy purses wrought in steel. His body was transparent; so that Scrooge, observing him, and looking through his waistcoat, could see the two buttons on his coat behind.Scrooge had often heard it said that Marley had no bowels, but he had never believed it until now.

Together, the ghosts carry out the near demolition of Scrooge’s spirit. He is forced to confront his increasing loneliness in the world as well as the losses his self-imposed spiritual isolation has incurred. He is forced to recognize that his current state is of his own making. First, he rejects the sort of kindness Fezziwigg displayed for him, then the love of his fiancée. Every chance he had to be a better man, he ultimately rejected in favor of hoarded gold, wealth he didn’t even benefit from. The Ghost of Christmas Past compels him to see the warmth- and love-filled family life of the woman he was once engaged to. Jovial as he is, the mirthful Ghost of Christmas Present is the hardest on Scrooge, throwing back his own words at him.

“If these shadows remain unaltered by the Future, none other of my race,” returned the Ghost, “will find him here. What then? If he be like to die, he had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.”

Scrooge hung his head to hear his own words quoted by the Spirit, and was overcome with penitence and grief.

“Man,” said the Ghost, “if man you be in heart, not adamant, forbear that wicked cant until you have discovered What the surplus is, and Where it is. Will you decide what men shall live, what men shall die? It may be, that in the sight of Heaven, you are more worthless and less fit to live than millions like this poor man’s child. Oh God! to hear the Insect on the leaf pronouncing on the too much life among his hungry brothers in the dust!”

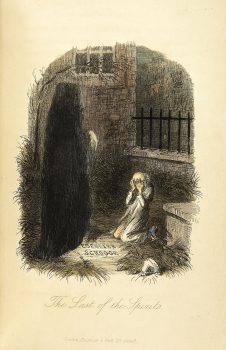

For all the horrors Scrooge and the reader are subjected to, Dickens doesn’t stint on some moments of beauty and grace. Following their visit to the Cratchits, the Ghosts of Christmas Present and Scrooge fly out over the English countryside to see the spirit of Christmas expressed in lowly, homely places, first a miner’s hut, then a lighthouse, and finally aboard a ship. For me, though my favorite single moment and one of the most magical is Scrooge’s first encounter with past Christmas and himself as a child and how he survived being left alone in his cold and decaying school for the holiday.

The Spirit touched him on the arm, and pointed to his younger self, intent upon his reading. Suddenly a man, in foreign garments: wonderfully real and distinct to look at: stood outside the window, with an axe stuck in his belt, and leading by the bridle an ass laden with wood.

“Why, it’s Ali Baba!” Scrooge exclaimed in ecstasy. “It’s dear old honest Ali Baba! Yes, yes, I know! One Christmas time, when yonder solitary child was left here all alone, he did come, for the first time, just like that. Poor boy! And Valentine,” said Scrooge, “and his wild brother, Orson; there they go! And what’s his name, who was put down in his drawers, asleep, at the Gate of Damascus; don’t you him! And the Sultan’s Groom turned upside down by the Genii; there he is upon his head! Serve him right. I’m glad of it. What business had he to be married to the Princess!”

To hear Scrooge expending all the earnestness of his nature on such subjects, in a most extraordinary voice between laughing and crying; and to see his heightened and excited face; would have been a surprise to his business friends in the city, indeed.

“There’s the Parrot!” cried Scrooge. “Green body and yellow tail, with a thing like a lettuce growing out of the top of his head; there he is! Poor Robin Crusoe, he called him, when he came home again after sailing round the island. ‘Poor Robin Crusoe, where have you been, Robin Crusoe?’ The man thought he was dreaming, but he wasn’t. It was the Parrot, you know. There goes Friday, running for his life to the little creek! Halloa! Hoop! Halloo!”

Then, with a rapidity of transition very foreign to his usual character, he said, in pity for his former self, “Poor boy!” and cried again.

From the start of his nighttime journey, we learn Scrooge has some tenderness within, even if only for himself at this point. There would be no point to Marley’s efforts if there was no hope. But there is hope, and there is redemption, and by extension, added hope for those around him. Tiny Tim will live, the Cratchits and Nephew Fred will prosper, and the whole of London will be a better place for it.

From the start of his nighttime journey, we learn Scrooge has some tenderness within, even if only for himself at this point. There would be no point to Marley’s efforts if there was no hope. But there is hope, and there is redemption, and by extension, added hope for those around him. Tiny Tim will live, the Cratchits and Nephew Fred will prosper, and the whole of London will be a better place for it.

If it isn’t obvious, I don’t have much to say about A Christmas Carol. It must be one of the most recognizable and read works of literature in English, if not any language, so there’s nothing I imagine there’s nothing I can imagine that hasn’t been written or said before. So, I’ll leave you with an admonition to just go secure a copy and take the hour or so it might take to read it. Dickens’s story preaches — and it is definitely a Christian story — about the obligations every man and woman have to the rest of humanity as well as the holding out of the promise of redemption and grace for even the most flint-hearted misers. In a time when those seem in short supply, it’s probably the right moment to read this, even if you already have.

PS: I mentioned several of the film adaptations earlier. For me, and most people I know, the Alastair Sim version is the best. I do know several strong (very strong!) partisans for the Reginald Owen film, but they are misguided, at best. However, I just was directed to an essay titled: A Grand Yuletide Theory: The Muppet Christmas Carol is the Best Adaptation of A Christmas Carol.

I might not agree with its overall premise, but I do agree that the three Christmas ghosts are among the very best of any depictions of them, including the original illustrations for the story by John Leech.

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before or for a very long time. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

I have a soft spot for the Owen film, mostly because I think Owen was a fine Scrooge, but the movie as a whole does fall far below MGM’s usual standard for literary adaptations, which is strange considering their magnificent versions of David Copperfield and a Tale of Two Cities. I watch the Alastair Sim version every year; he’s by far the best reformed Scrooge.

The Alastair Sim version was the first movie I ever saw. I was five-years-old and it showed up on television one afternoon around Christmas. It affected me deeply and has remained my favorite version over the years although Richard Williams’ animated adaptation from the early seventies (with Sim voicing Scrooge) is just exquisite and hews very closely to the text. I strongly recommend it to any “Christmas Carol” fan.

As someone who doesn’t toss Christmas to the curb January 1st but celebrates the full twelve-day holiday (I actually keep my decorations up through Candlemass in February) I genuinely appreciate your posting this lovely piece of after “the big day .” Happy Holidays.

I’ve been meaning to track down that animated one. We did watch the Mr Magoo one, which was surprisingly fun. I like the Candlemass date. We keep them up a little longer, but I don’t think I could convince my wife to let them linger until then.

I recently saw the Owen version, which I thought was just fine, but I wouldn’t put it at the top. I do have great fondness for the Muppet Christmas Carol, which for one thing, by most accounts, uses more of Dickens’ words than any other movie. I have not see the Sim version in decades, I should remedy that.

Dickens’s words! That’s exactly what we thought rewatching it the other night, just how much of the actual text it included.

The stake of holly through the heart sounds curiously like the method that’s used to suppress Lucy Westenra’s vampirism in Dracula, though that novel postdates Dickens by a good bit.

The Clive Donner made for TV movie, with George C Scott is my favorite. Scott makes an excellent Scrooge both before and after redemption.

Scott is a fine Scrooge, but my favorite from that production is Edward Woodward as the Ghost of Christmas Present – the best GCP of them all (with a nod to Carol Kane in Scrooged.)