From Mystery to Horror: Darker than You Think by Jack Williamson

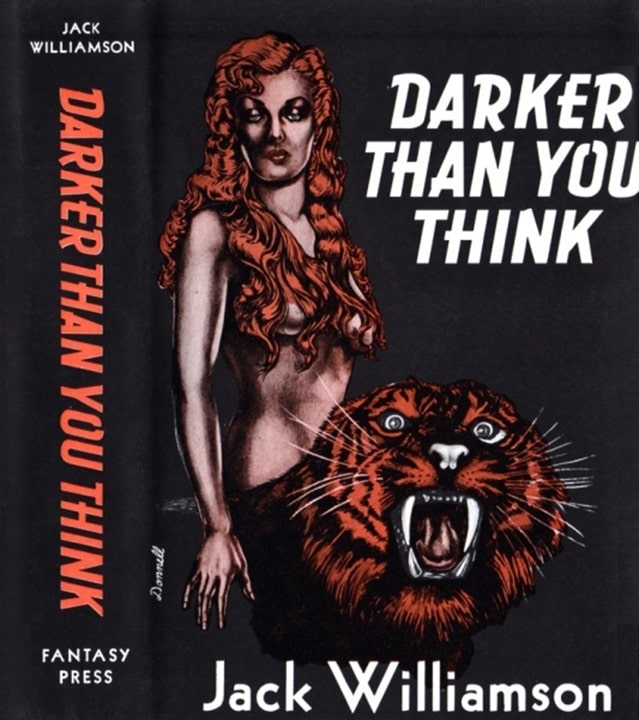

Darker Than You Think (Fantasy Press, 1948). Cover by A. J. Donnell

Jack Williamson had an impressively long career in science fiction, from the pre-Campbell era into the twenty-first century. His first sale, in 1928, was to Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing Stories; his last book came out in 2005, the year before his death at 98. Darker than You Think is one of the high points of that career, published in 1948 as a novel expanded from a 1940 novella that appeared in John W. Campbell’s fantasy magazine Unknown.

Despite this venue, though, Darker than You Think is highly rationalized “fantasy,” to the point where it’s more accurately described as science fiction. Near the end of the novel, an important secondary character, Sam Quain, tells the protagonist that “supernatural” really means “superhuman.”

[Click for images bigger than you think.]

Inside cover flap, Fantasy Press hardcover edition

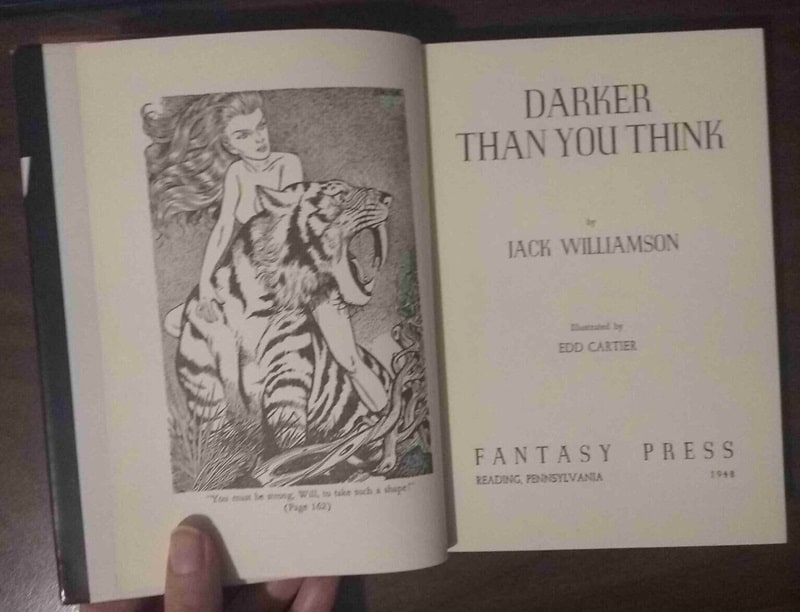

Frontispiece. Art by Edd Cartier

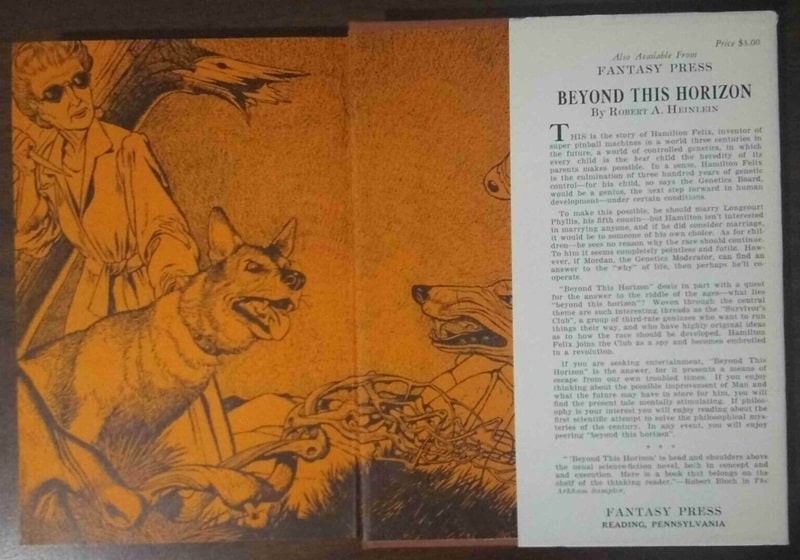

End flap, advertising Beyond This Horizon by Robert A. Heinlein

Williamson both appeals to quantum mechanical ideas about probability to rationalize the mysterious powers that his characters contend with, and discusses the inheritance of these powers as recessive genetic traits. His account describes what’s now called polygenic inheritance, an idea that was then becoming known among biologists trying to reconcile Mendelian genetics with Darwinian evolution.

All of this is the subject of a plot about recognition, or what Aristotle called anagnorisis and considered the mark of the best forms of tragedy — the moment where a character makes a crucial discovery, as in Oedipus’s realization that he himself is the monstrous sinner who has brought divine wrath down upon Thebes. One of Dorothy Sayers’s essays suggested that Aristotle’s account of plot structures can be taken as a theory of the mystery novel, and while Darker than You Think isn’t a mystery in the classic sense — its several deaths mostly take place on stage — it has a lot of the elements of noir.

|

|

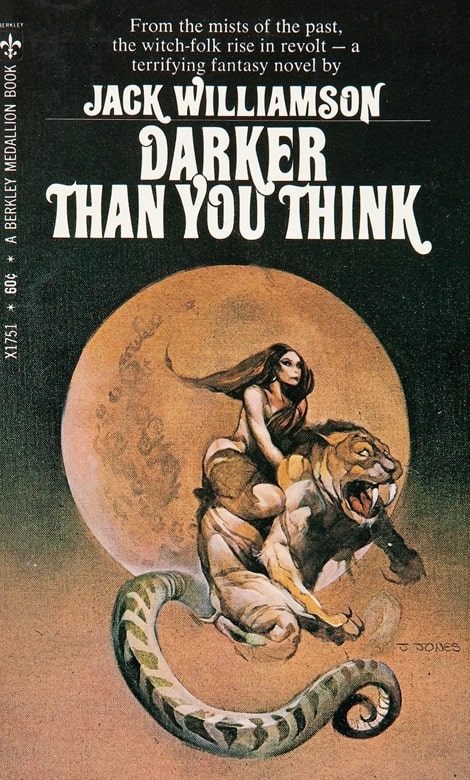

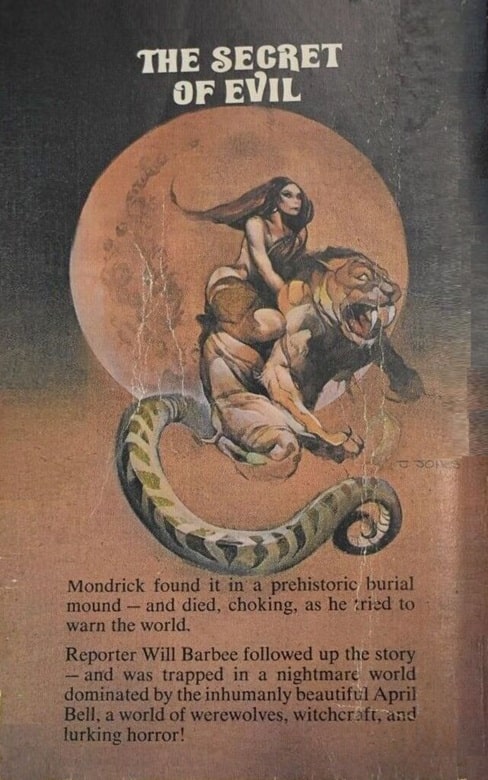

Darker Than You Think (Berkley Medallion, October 1969). Cover by Jeff Jones

Its protagonist, Will Barbee, is a good fit to the “tarnished knight” archetype of mystery writers such as Hammett and Chandler: Not a detective but a reporter for a local newspaper whose owner is deeply involved in corrupt urban politics. Barbee is cynical about his work, and a heavy drinker, who can’t function without alcohol.

When a scientific expedition comes back from Central Asia, it’s natural that he’s sent to cover it; and when the expedition’s leader, Lamarck Mondrick, dies in the midst of a speech announcing his findings, it’s plausible that Barbee’s psychic sense for news gets called into action, forcing him to pursue the truth even when he would rather not believe it. As he does so, the story morphs from mystery to horror, leading up to a crucial revelation.

|

|

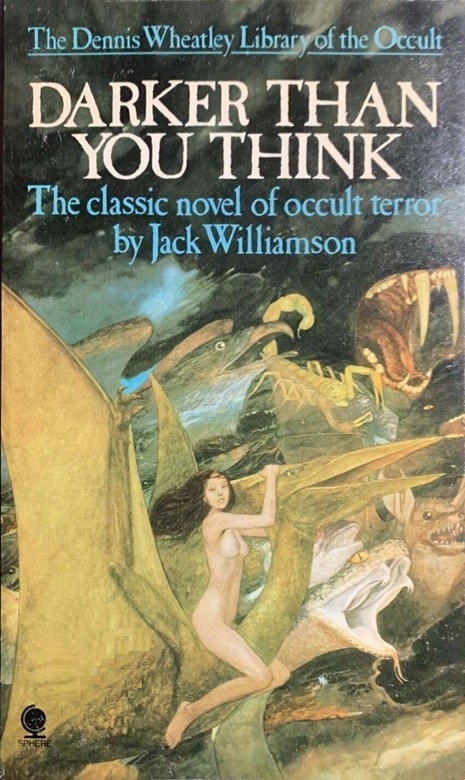

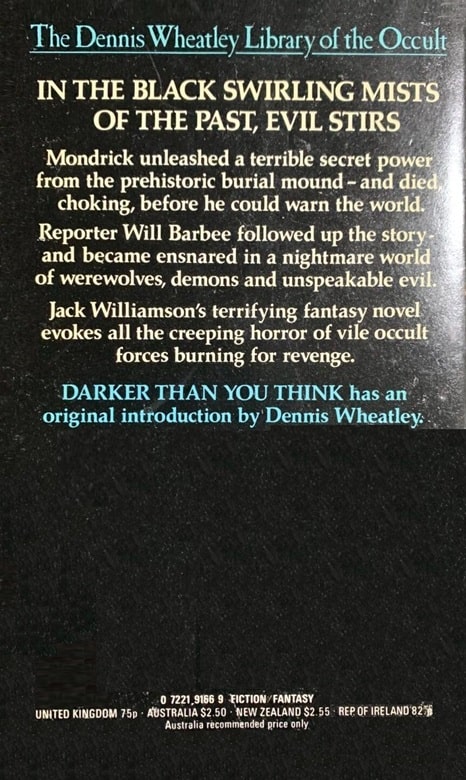

Darker Than You Think (Sphere, November 1976). Cover artist unknown

It’s well known that Williamson underwent psychoanalysis in the 1930s, and Darker than You Think has been described as reflecting the insights he gained from it. But I find it striking that in Barbee’s crucial conversation with Quain, Quain asserts that Freud was never able to explain human evil.

Mondrick, though, says Quain, had discovered the explanation, in human prehistory: The emergence of a central Asian race of psychically gifted predators, eventually overcome by the far more numerous ungifted human beings they preyed on (Williamson makes the ecologically valid point that the prey have to outnumber the predators), but able to leave behind hybrid descendants, in a way that curiously anticipates recent findings about the persistence of Neanderthal and Denisovan genes in European and Asian Homo sapiens.

|

|

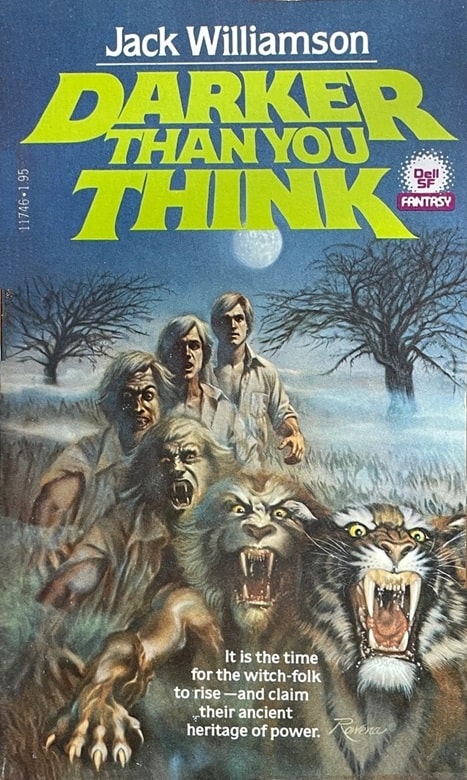

Darker Than You Think (Dell, July 1979). Cover by Rowena Morrill

(note the misspelling of her last name on the back of the book).

The most powerful of these descendants were remembered in legends about pagan gods and heroes; the more numerous ones with only minor gifts were called witches.

And this brings in the novel’s primary female character, April Bell, whom Barbee meets and is fascinated by in the first chapter. Like many science fictional heroines, she’s a strikingly attractive redhead (Heinlein is well known for women characters with red hair, but there are also E.E. Smith’s Clarrissa MacDougal, Poul Anderson’s Virginia Graylock, and Cordwainer Smith’s C’Mell).

She first appears as a newly hired reporter, covering the Mondrick story for another paper, who asks Barbee for advice. Superficially she fits the “manic pixie dream girl” pattern described in TVTropes, starting with her appearing at the airport carrying a black kitten in a basket. But as Barbee repeatedly encounters her, she turns into a femme fatale, in classic noir style — though the other important female character, Mondrick’s widow, is cast more as a maternal figure than as a naïve damsel; she’s not exactly a Betty to Bell’s Veronica. (Given the psychoanalytic connection, though, Lamarck Mondrick’s breaking off ties with Barbee might be given an Oedipal reading.)

|

|

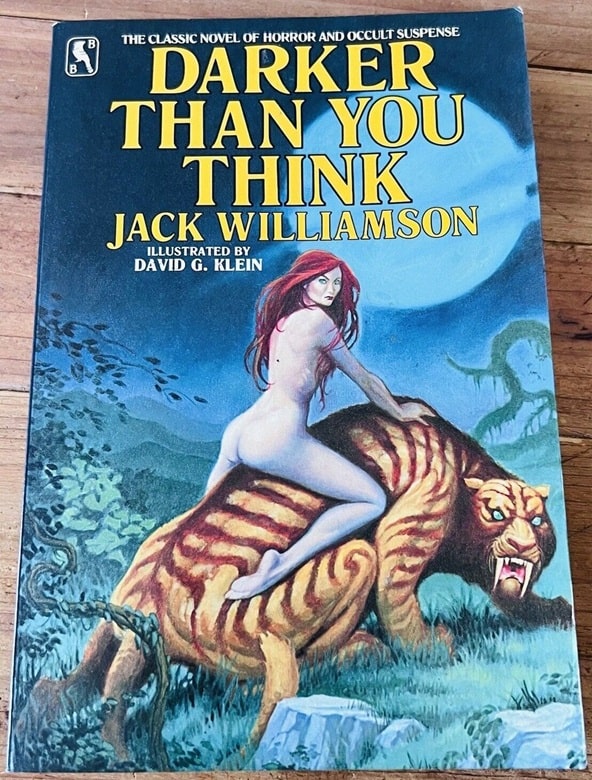

Darker Than You Think (Bluejay Books, August 1984). Cover by David G. Klein

Both women turn out to have potent psychic gifts, and Bell tells Barbee a life story of being raised by a hostile and violent stepfather who thought of her as a witch, putting her in the third role of a supplicant. Barbee’s compelling attraction to her is the primary motor of Williamson’s plot.

What Williamson actually presents in Darker than You Think is a different view of the unconscious mind: one inspired not by Freud but by Nietzsche. In contrasting master morality and slave morality, Nietzsche suggested that the two, originally distinct, had become intermingled over the course of history (and perhaps in prehistory, a speculation inspired by philological evidence). Nietzsche’s account of this is mainly in cultural terms, but he hints at genetic hybridization as well.

In Darker than You Think, master and slave are not simply two different moralities or cultures, but two different strains of humanity. Williamson’s story develops into one of internal struggle of Barbee’s conscious mind against his own predatory impulses, which gives this novel unusual depth and complexity for a work of pulp fiction.

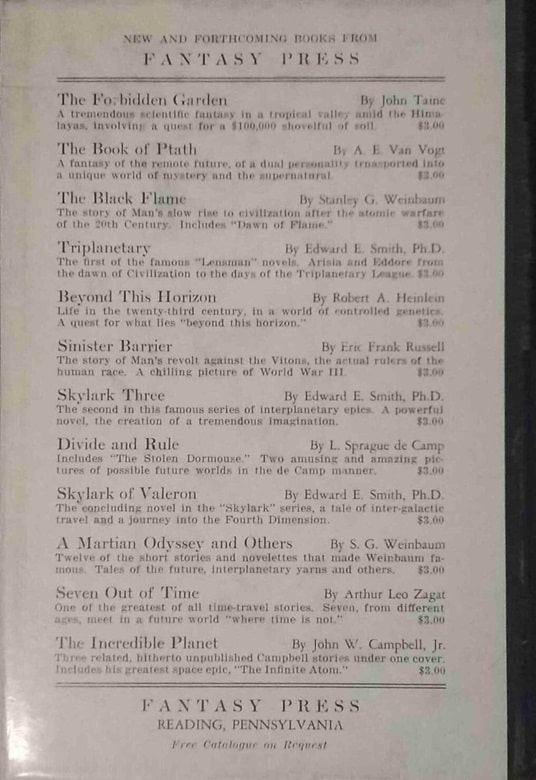

Back cover of Fantasy Press hardcover, advertising their 1948 catalog

Williamson suggests that the unconscious mind is a realm not simply of repressed sexuality, but of will to power, anthropophagous desires, and witchcraft — and of traces of ancient paganism. Bringing back the superman, he seems to be saying, would be anything but harmless, a conclusion that Nietzsche might have welcomed.

Also paralleling Nietzsche, Quain’s account of human history makes the monotheistic religions the basis of an ongoing struggle not merely against paganism, but against the real superhuman beings whose activities inspired its myths.

Jack Williamson

Darker than You Think lacks one of the appeals of a lot of pulp fiction: Its protagonist has strikingly little agency. Most of the crucial changes in his life in the course of the story aren’t decisions of his, and such decisions as he does make often turn out to be ineffective or to have unintended consequences.

But given the novel’s theme and premise, this is probably necessary. Will Barbee spends much of the novel as a flawed and pathetic figure, but it would be harder to sympathize with him if he were consciously in control of the actions he performs.

William H. Stoddard is a professional copy editor specializing in scholarly and scientific publications. As a secondary career, he has written more than two dozen books for Steve Jackson Games, starting in 2000 with GURPS Steampunk. He lives in Lawrence, Kansas with his wife, their cat (a ginger tabby), and a hundred shelf feet of books, including large amounts of science fiction, fantasy, and graphic novels. His last article for us was a look at the Transhuman Space RPG by David Pulver.

I liked Darker Than You Think.

When I started reading SF magazines Williamson was still publishing. He had a long career as you mentioned.

Williamson is a big hole in my reading that needs to get filled.