Science is Sorcery

|

|

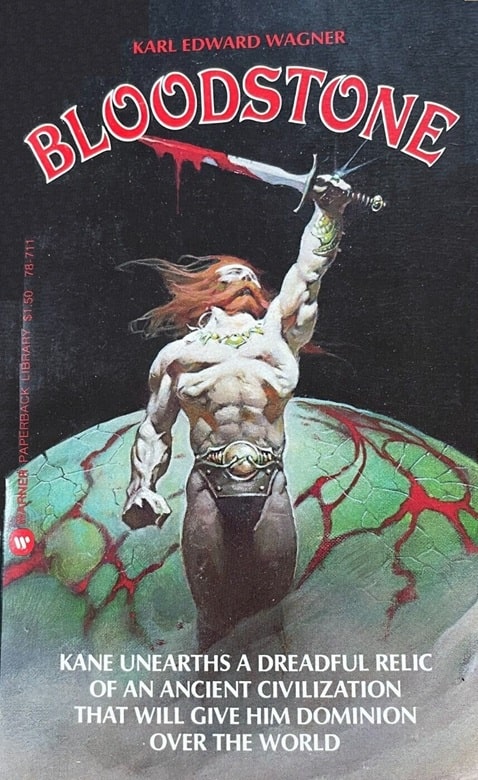

Bloodstone (Warner, March 1975). Cover by Frank Frazetta

“Kane’s power is that of science, not sorcery — although with elder-world science, the distinction becomes blurred. But then, to the untutored minds the distinction is difficult to grasp, for this lies in understanding the forces at work, and in the laws they obey. For example, to produce a deadly sword to wield in battle, a master smith will use secrets of his craft to smelt choice iron into steel, forge steel into tempered blade, then balance, hone and haft the blade to the best of his art. Similarly, a wizard may utilize the secrets of his craft to forge a sword of starfire and incantations. Both swords seem magic to some club-swinging apeman, such as legend places on lands unknown to our civilization, but clearly one is born of science, the other spawned by sorcery…”

—Karl Edward Wagner, Bloodstone

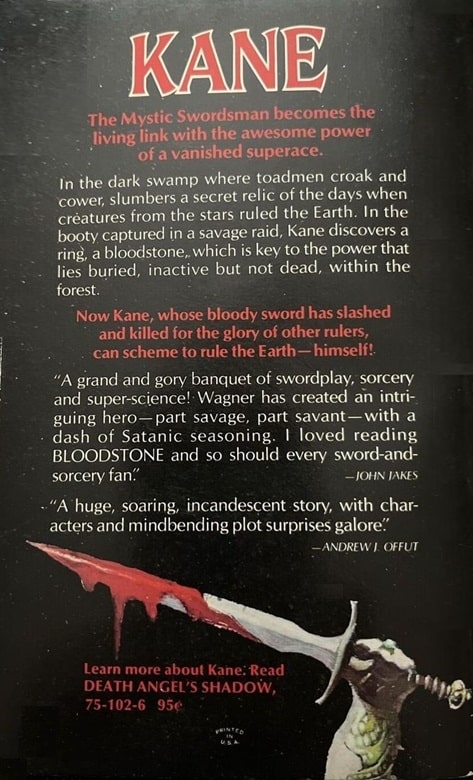

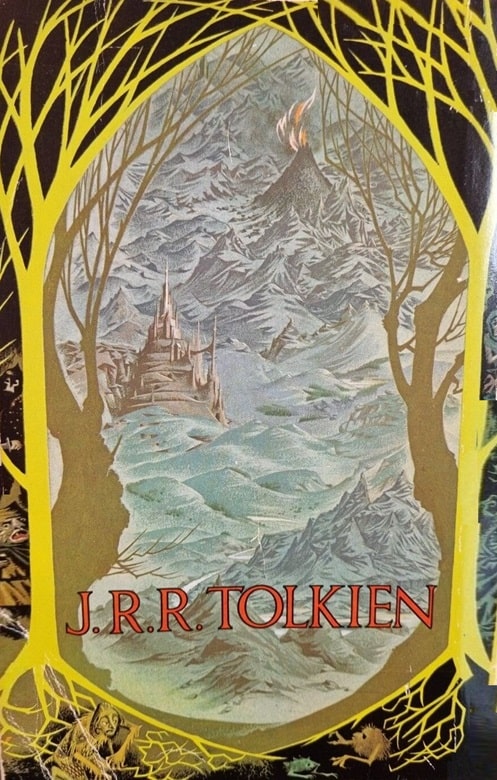

In the hobby of tabletop role-playing games, the influence of J.R.R. Tolkien looms prominently, and the reason for this makes perfect sense: By the mid- to late 1960s, Tolkien fever (i.e., fervent esteem for The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings) was reaching epic proportions, fueled by the mass market release of affordable paperbacks published by Ballantine Books. “Frodo Lives!” became a counterculture slogan on buttons, bumper stickers, and T-shirts. In the form of graffiti, it was spray-painted in subways and under bridges. Wargaming enthusiasts of the American Midwest were not immune to the hypnotic effect of The Ring, and in one wargame, called Chainmail (Gygax and Perren, 1971), a 15-page “Fantasy Supplement” in the back of the rules proved to be a primary progenitor of the world’s most popular tabletop role-playing game, Dungeons & Dragons.

[Click the images for sorcerous versions.]

|

|

The Lord of the Rings (George Allen & Unwin, 1971). Cover by Pauline Baynes

On the surface, traditional D&D1 always looked and felt like an expression of The Fellowship of the Ring with its fighters, magic-users, rangers, dwarves, elves, halflings, and so forth. A player character (PC) party typically was comprised of a collection of unique individuals, each of whom represented an archetypal hero possessed of his or her own skills and abilities. Also, their typical adversaries could include dragons, goblins, orcs, treants (ents), and trolls.

Collectively, these recognizable ingredients form the recipe for a “high fantasy” role-playing style, but I would contend that these ingredients merely inform but one thematic style or mode of play and is not representative of the full array of possibilities as presented by (and even advocated by!) the originators of tabletop role-playing games: Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson.

|

|

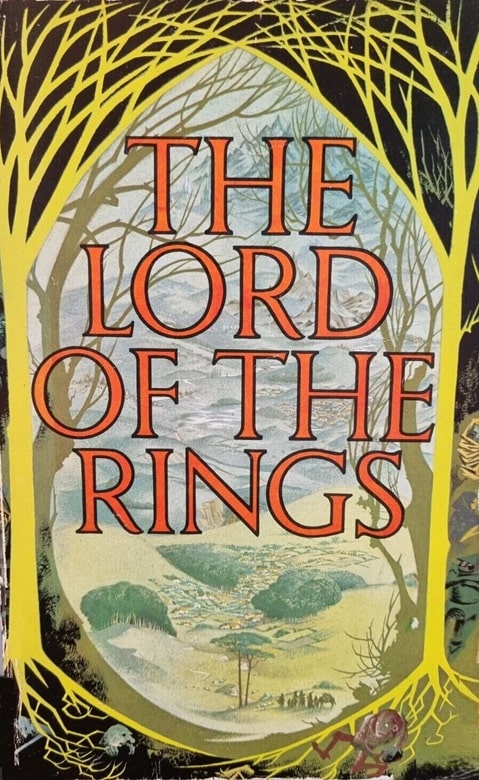

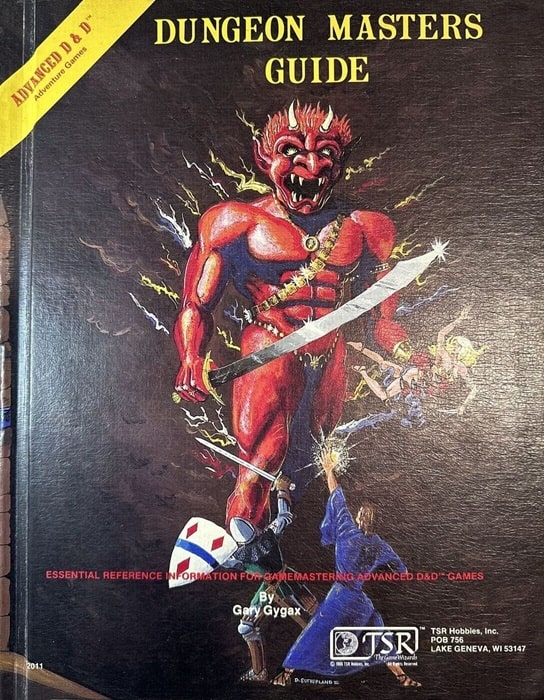

Dungeon Masters Guide (TSR Hobbies, 1979). Cover by David C. Sutherland III

In 1979, the Dungeon Masters Guide for Advanced Dungeons & Dragons was published by TSR. Written by Gary Gygax and featuring an iconic cover painting by David Sutherland, the DMG was my first hardcover AD&D book, which I purchased as a preteen with my paper route earnings. Prior to this, I had been using the Holmes D&D set, but my friends and I eventually transitioned to AD&D. The DMG was filled with systems, procedures, advice, tools, and guidance on the creation and maintenance of a longform D&D campaign, which is the ultimate expression of tabletop gaming.

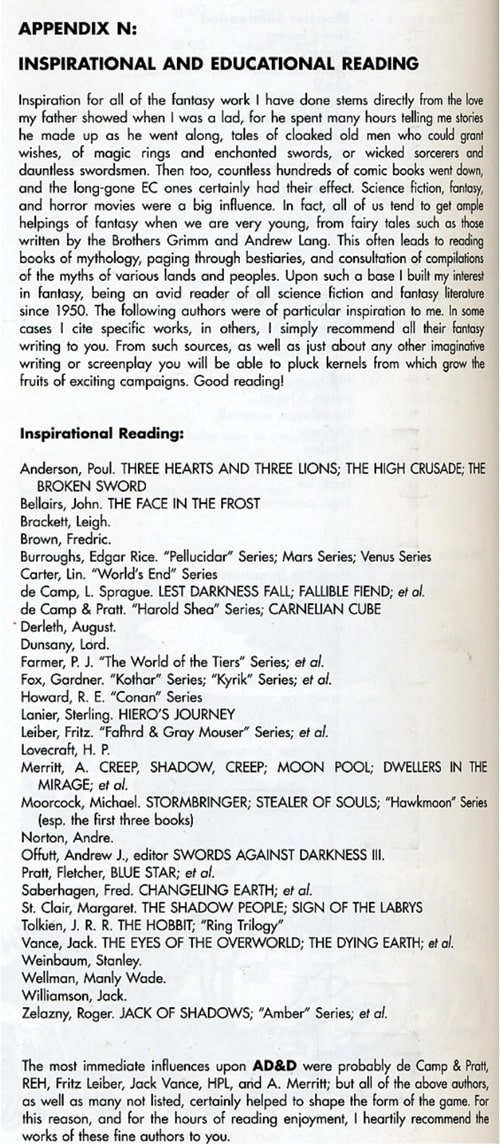

The appendices of the DMG went on to provide yet more resources, including but not limited to random dungeon creation, random wilderness creation, traps, tricks, summoned monsters, etc. One appendix of this volume, however, has become increasingly popular over the past decade, and if you are reading this article, chances are you already know what I am referring to. It is, of course, “Appendix N: Inspirational and Educational Reading.” In it, Gygax states:

The following authors were of particular inspiration to me. In some cases I cite specific works, in others, I simply recommend all their fantasy writing to you. From such sources, as well as just about any other imaginative writing or screenplay you will be able to pluck kernels from which grow the fruits of exciting campaigns. Good reading!

In Appendix N, the listed authors and their respective cited works seemed to be (at the time) a typical reading list for any enthusiast of fantasy, horror, and science fiction. Now, however, this list has become a thing of endless discussion, speculation, and reflection, elevated to far greater importance than, say, “Appendix O: Encumbrance of Standard Items.”

Appendix N by Gary Gygax. From the Dungeon Masters Guide

Indeed, Appendix N is the subject of blogs, podcasts, reading clubs, forum discussions, social media gatherings, and more. But for those of us who “grew up D&D” in the 70s and 80s, Appendix N merely was a nifty resource for the bookworms among us seeking something new or different to read. While we understood that these works of fiction helped to inspire the game, we largely were living in the moment and not deeply considering its implications as modern aficionados of Appendix N do so today.

Now, debates regarding “glaring omissions” often crop up; too, detractors of authors and/or works not deemed worthy of inclusion are not uncommon debates. Indeed, I am not exempt from occasionally voicing such thoughts and opinions. In fact, the author I quoted in the epigraph of this article was, in my opinion, one such woeful omission.

So, how did the fourteenth appendix buried in the back of the DMG become such a popular topic for several of the more invested enthusiasts of tabletop role-playing games?

I tend to think it has a lot to do with the longevity of D&D and the consequential rise of a historical interest in the roots of the hobby itself. Because D&D has been around for about half a century, it has evolved into something that is more than simply a pop culture phenomenon. Thus, we can’t help but examine and tease out what or why D&D is what it is, and Appendix N is a natural place to examine.

It helps us to understand some of the preferred ingredients of the head chef himself. As I mentioned, it is easy to see the Tolkien influence, but Gygax himself often diminished JRRT’s significance. I had the opportunity to work with Mr. Gygax at the end of his life, and he once expressed to me that while he liked The Hobbit very much, he was far less inspired by The Lord of the Rings.

Some would suggest that Gary’s less-than-enthusiastic view of Tolkien’s influence on D&D was the result of the Tolkien estate slapping him on the wrist in the 1970s for including words like “hobbit” and “Balrog” in the original booklets. This may well be true, but when I read the works of Robert E. Howard, Fritz Leiber, and Jack Vance, it “feels” more like D&D. I would contend that Gary was equally (if not more) inspired by those three authors as he was by Tolkien. Regardless of the particulars, it is an accepted truth that D&D is a melting pot of inspirations and influences, not the least of which include science fiction elements, as I will attempt to demonstrate.

In 1962, Arthur C. Clarke’s Profiles of the Future was published. It contained Clarke’s Three Laws, the third of which is best known and suits this article well: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” This corroborates the epigraph of this article, quoted from KEW’s Bloodstone, which I feel applies to fantasy gaming, too.

Thundarr the Barbarian (Ruby-Spears Productions, 1980-81)

In the scope of the campaign milieux, how do we, as Dungeon Masters, Game Masters, or Referees distinguish between sorcery and science? Ever since the halcyon days of my youth, if you asked me what my favorite cartoon was, I would tell you Thundarr the Barbarian (though in the 1990s, Batman: The Animated Series certainly presented a compelling contender). Thundarr remains my personal favorite, because it epitomizes the kind of thematic content that I most enjoy writing: far-flung worlds in which artefacts of sorcery are indistinguishable from the scientific relics of a bygone age.

Thundarr’s beloved “sunsword” is a hilt that, when activated, emits a blade of powerful energy. It can deflect other energy attacks, magical attacks, and it can laser through nearly any material. Too, it can disrupt sorcerous spells and like effects. In one episode, “Master of the Stolen Sunsword,” it must be recharged, which prompts the question: Is Thundarr’s sword a magical weapon or a scientific one? It probably depends on whom you ask. It might be sorcery to a caveman and science to an ancient Atlantean astronaut.

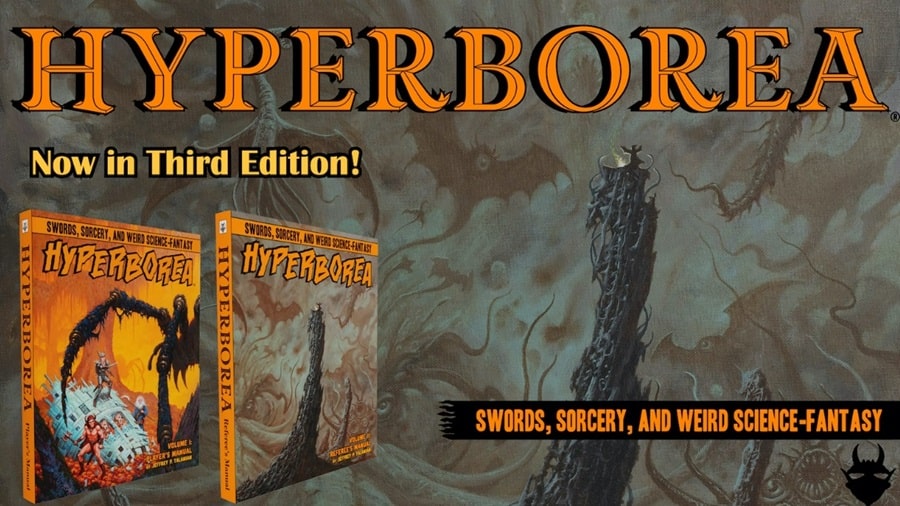

Hyperborea Third Edition (North Wind Adventures)

Since 2010, I have been publishing adventure supplements for Hyperborea, a tabletop role-playing game that I created. What started off as something I wanted to play with my beer-drinking buddies (and sell to a few interested fellow gaming enthusiasts as time permitted) has, to my delight, turned into a full-time occupation.

Hyperborea primarily is inspired by the fiction of Robert E. Howard, H.P. Lovecraft, and Clark Ashton Smith. Beyond the Weird Tales “Big Three” triumvirate, its setting draws inspiration from the likes of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Fritz Leiber, Abraham Merritt, Michael Moorcock, Jack Vance, and Karl Edward Wagner. Hyperborea doesn’t have elves, hobbits, or gnomes. There are dwarfs, but they are greedy, venal, lecherous, pale-skinned brutes that dwell in the cavernous depths of Underborea.

Hyperborea Third Edition (North Wind Adventures)

By design, Hyperborea is not intended to be yet another expression of Professor Tolkien’s incredibly imaginative fiction. Rather, it is a far-flung, futuristic flat earth setting in which the sea spills eternally into The Black Gulf, and the sun is a bloated red giant whose days are numbered. Hemmed in by the mystical Boreas (North Wind), Hyperborea is a world of swords, sorcery, and weird science-fantasy.

A necromancer might wield a magical wand, whilst his comrade, an armored cataphract, might wield both a sword and a radium pistol. They might venture into caverns of ape-men, but the ape-men might be ruled by an alien being that utilizes a master computer to diabolical effect. When I was brainstorming how to create the Hyperborea that I wanted to play, I happened to be in one of my many H.P. Lovecraft phases.

Astounding Stories, June 1936, containing

“The Shadow Out of Time” by H.P. Lovecraft. Cover by Howard V. Brown

At the time, I was reading The Shadow out of Time, when I had an epiphany. It was this paragraph that galvanized me:

There was a mind from the planet we know as Venus, which would live incalculable epochs to come, and one from an outer moon of Jupiter six million years in the past. Of earthly minds there were some from the winged, star-headed, half-vegetable race of paleogean Antarctica; one from the reptile people of fabled Valusia; three from the furry pre-human Hyperborean worshipers of Tsathoggua; one from the wholly abominable Tcho-Tchos; two from the arachnid denizens of earth’s last age; five from the hardy coleopterous species immediately following mankind, to which the Great Race was some day to transfer its keenest minds en masse in the face of horrible peril; and several from different branches of humanity.

In TSooT, Lovecraft blended Smith’s pre-human race (the Voormis) of Hyperborea, Howard’s antediluvian Serpent Men of Valusia, his own star-headed Elder Things of Antarctica, and more. It never escaped me that Howard, Lovecraft, Smith, and some of their other peers loosely shared their creations, but when I read the above paragraph, I felt a greater appreciation for the melting pot concept embraced by Gygax and his peers when they were creating and expanding the various worlds of Dungeons & Dragons.

|

|

|

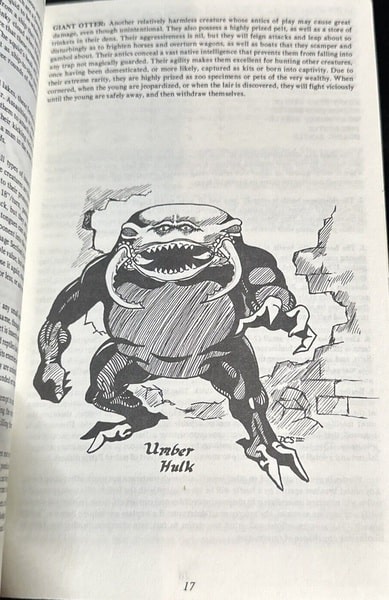

Dungeons and Dragons Supplement II: Blackmoor by Dave Arneson

(Tactical Studies Rules, 1975), containing “The Temple of the Frog.” Cover and

interior illustrations by David C. Sutherland III, Mike Bell, and Tracy Lesch

I’d like to believe that one reason for Hyperborea’s small amount of success is that it honors a key component of tabletop gaming’s roots: the inclusion of sci-fi elements. If we go back to 1975, the first published D&D adventure was found in the pages of Supplement II: Blackmoor, by Dave Arneson. It was called “Temple of the Frog,” and it contained various sci-fi elements sprinkled throughout, such as the medical kit and the communications module.

If you go to 1980, one of Gary Gygax’s most famous adventure modules, Expedition to Barrier Peaks takes place within the confines of a spaceship that has crashed in a mountain range. It has laser weapons and robots within. Even the aforementioned Dungeon Masters Guide contains examples of sci-fi elements, such as the Apparatus of Kwalish, Machine of Lum the Mad, Mighty Servant of Leuk-O, and so forth. In one subsection of the DMG, called Mutants & Magic, Gygax states:

Readers of The Dragon might already be familiar with the concept of mixing science fantasy and heroic fantasy from reading my previous article about the adventures of a group of AD&D characters transported via a curse scroll to another continuum and ending up amidst the androids and mutants aboard the Starship Warden of Metamorphosis Alpha. Rather than go back over that ground again, it seems more profitable to discuss instead the many possibilities for the DM if he or she includes a gateway to a post-atomic war earth a la Gamma World. The two game systems are not alien, and interfacing them is not difficult.

Science fiction elements are in the very DNA of tabletop role-playing games. If a group of gaming enthusiasts elects to eschew such elements from their game, that is perfectly fine. Do what you enjoy.

|

|

Hawkmoon volumes 1 and 4: The Jewel in the Skull and The Runestaff

(Tor, January and December 2010). Covers by Vance Kovacs

But what I would caution against is the assumption that sci-fi elements are inappropriately tacked on to fantasy games and settings — an incongruent window dressing, if you would. This simply is not the case. Adding a dash of sci-fi, like perhaps the technological relics of a lost age, can really spice up your game, creating a sense of mystery and wonder for your naturally curious players. When players are left speculating how and why something is, the campaign becomes more immersive, its participants more invested. Give it a whirl!

Some of my favorite stories that blend fantasy and sci-fi are the Hawkmoon series, by Michael Moorcock; the Kane series, by Karl Edward Wagner; and Jack of Shadows, by Roger Zelazny. Sometimes the infusion of sci-fi can be subtle, like in Larry Correia’s Saga of the Forgotten Warrior, in which the reader is immersed in a story that, on the surface, appears to be classic swords-and-sorcery, but as it progresses, you begin to realize that its underpinnings are in science fiction.

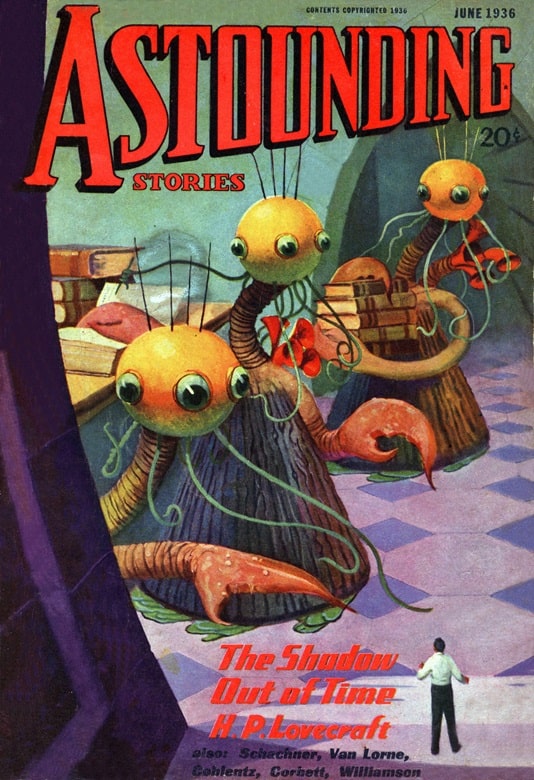

The first six issues of Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth (DC Comics, 1972-73). Art by the great Jack Kirby

Lastly, I would be remiss if I did not mention my fascination with the comic book Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth, created by Jack “King” Kirby, and published by DC Comics. In this post-apocalyptic setting of Earth A.D. (Earth After Disaster), most of humanity has been wiped out, and thanks to a drug called Cortexin — combined with radiation — many species of animals have evolved to intelligent bipedalism, whilst most of the remnants of humanity have regressed to savagery. Kamandi must deal with evil energy beings, possession, gorilla commandos, robot gangsters, tiger-men, and countless other weird and wonderful antagonists that fill the pages of this incredible run.

There are countless other examples of sci-fi blended into fantasy, and I would love to hear about some of your favorites. Happy reading, and keep those sunswords charged, my friends.

1 Modern descendants of the Dungeons & Dragons game appear less influenced by The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings; rather, they appear to draw inspiration from a variety of modern pop culture sources, including Japanese anime such as Dragon Ball, MMORPGs such as World of Warcraft, and miniatures games such as Warhammer. Indeed, modern D&D is oft stylized with anime-styled art in which tattooed, body-pierced, blue-haired characters wield impossibly sized weapons. These difficult-to-kill heroes are possessed of super-powers the likes of which would make Gandalf appear feeble. So it goes.

Jeffrey P. Talanian’s last article for Black Gate was a look at Castle Amber by Tom Moldvay. He is the creator and publisher of the Hyperborea sword-and-sorcery and weird science-fantasy RPG from North Wind Adventures. He was the co-author, with E. Gary Gygax, of the Castle Zagyg releases, including several Yggsburgh city supplements, Castle Zagyg: The East Mark Gazetteer, and Castle Zagyg: The Upper Works. Read Gabe Gybing’s interview with Jeffrey here, and follow his latest projects on Facebook and at www.hyperborea.tv.

Fun article! I have (and play!) Hyperborea and I totally agree with you about the inclusion of science fiction elements can greatly increase the interest and awe in a creative endeavor. I personally don’t think there’s nearly enough of this mix.

Also, the Kane novels are bloody great. I own the Night Shade Books compilations and you’ll pry them out of my cold, (un)dead hands!

Lastly, those Hawkmoon covers are fantastic, I may have to see if I can get my hands on those bad boys.

Thanks for the writing!

Thank you for the kind words. I have the Night Shade collection, too, and despite my urge to start purging my book collection, this set I too will take to the grave. 😉

You know I’ve read many appendix N writers but I’ve never played any tabletop role playing games. It’s just coincidence that I know the authors.

I watched Thundarr again a couple of years ago and found that every episode had basically the same formula: Thundarr battles evil sorcerer. There’s some variation but it was repetitive. View individually the episodes were fun but as whole it was disappointing.

Growing up in a small town which did not have a well-stocked library but was able to get books from a nearby library, Appendix N provided a list of books to check out – I remember choosing the Runestaff books based on titles “The Jewel in the Skull” & “The Mad God’s Amulet”. As far as mixing science and magic – Christopher Stasheff’s “The Warlock in Spite of Himself” did this well, science and telepathy seen as magic. I also thought Andre Norton’s “Starman’s Son” (aka “Daybreak – 2250 A.D.”) captured the flavor of Gamma World as did Sterling Lanier’s “Hiero’s Journey” which I just re-read – it held up pretty well.

Great recommendations! Two of those I have never read, so I will look into them.

Great, thoughtful article, giving a lot of food for thought.

I’m in favor of mingling science with sorcery if it increases wonder. I’m against mingling science and sorcery if it reduces magic to a mundane pseudo-technology.

I concur.

Midi-clorians anyone?

And the original 1e DMG had a chapter or two specifically devoted to rules for crossing over AD&D with Gamma World or even Boot Hill!

I don’t think it’s entirely fair to tweak Gygax for not including KEW, given that most of the Kane books were being published in the mid-to-late 70s, after D&D had assumed its initial form.

Bloodstone is probably my favorite of the Kane novels, not least because of the combination of super-science and sorcery.

Yes, the blending of Gamma World and Boot Hill was included, for sure. Fair point on Gygax and KEW. Completely agree on Bloodstone. It’s my favorite, too, for the same reasons you cite.

Great article! I grew up with the old school D&D as well, and Thundarr, and Lovecraft, etc., etc. Your essay was a trip down memory lane for me. Thanks.

We tended to mix sci-fi and sorcery stuff together too back in the day as well. We didn’t see a hard line fast line between the genres. I think this notion was pretty popular at the time. Remember the Spellsinger saga by Alan Dean Foster? If memory serves, the main hero was sucked out of our present (or early 1980s equivalent) while he was smoking a joint into a medieval, fantasy past. I don’t remember technology per se making an appearance; but we didn’t blink at the idea of the modern world and fantasy worlds overlapping.

Never read that one, but I’ve read some of his film adaptions. Also, his Star Wars novel, Splinter in the Mind’s Eye, which I enjoyed.

I can unashamedly say that I read The Lord of the Rings in order to better understand the background of D&D, “white box” edition, before Appendix N was even a gleam in Mr. Gygax’s eye.

And I do enjoy the mix of science and magic, from even before the D&D mash-ups, as my first TTRPG was Empire of the Petal Throne, which posits a human space colony being suddenly cut off and reduced to Iron Age level technology (on a world that is painfully short of iron, no less). I have looked for other TTRPGs with similar mixing of tech and spells, so Skyrealms of Jorune was a source for several campaigns. Science fantasy, FTW!

Never played EotPT, but I’ve heard nothing but good things over the years.

What a marvelous article! I too, knew Gary in a much lesser extent as we rubbed shoulders at GenCon over the years! And I too learned about some of the aforementioned authors by Gary’s (now famous) appendix! We live in an Age of dark magic! Beware!

Iain M Banks once referred to Brian Aldiss as One of the Best SF writers Britain has ever produced

In addition to countless short stories, Aldiss wrote the inspiratory work, Non-Stop, which became the basis for Metamorphosis Alpha, and another novel, Hothouse, which won a Hugo award. These stories are rooted in the same soil as many of these others in your wonderful post, and by brilliant others in the comments

Bloodstone is my least favorite Kane novel, but my favorite Star Trek episodes involve bladed weapons, and I loved Thundarr the Barbarian. I don’t know what that says about me.

Congrats on turning a love into a full-time gig.

Hadn’t been aware that science-as-sorcery was considered its own sub-genre until this very illuminating article, so am feeling around for the edges of the category. Would Stanislaw Lem’s “The Cyberiad” be considered part of the science-sorcery realm?