Units of Conviction: Being Michael Swanwick

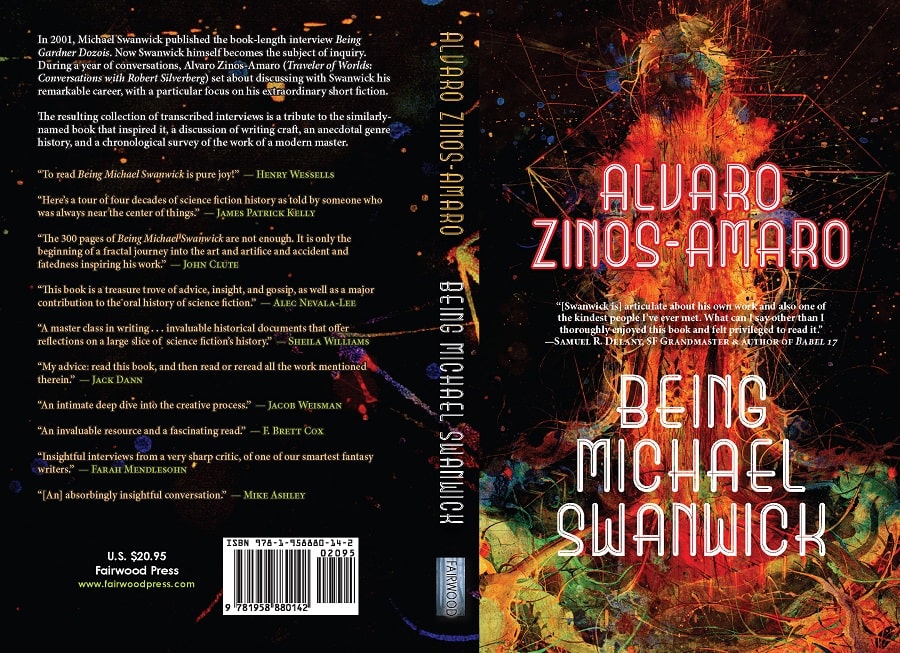

Being Michael Swanwick (Fairwood Press, November 21, 2023)

Prolificity is in the DNA of science fiction. H. G. Wells, whose most famous works date back to the 1890s, wrote some fifty novels, seventy non-fiction books, and one hundred short stories. Pick almost any SFWA Grand Master and you’ll encounter a bibliography that will engulf your life for many months, if not years. How many shelves to house the hundreds of books published, for instance, by Andre Norton, or Poul Anderson, or Michael Moorcock, or Jane Yolen?

A great many of the field’s best-known writers were, and in some cases still are, not just highly productive, but visibly so. The running tally of Isaac Asimov’s books was widely publicized and known — David Letterman, for instance, said on national television in 1980, “My next guest’s most recent published work is his two hundred and twenty-first book” — and many notable genre names remained in the spotlight because they always seemed to have a new book in the offing, frequently writing across genres or penning long-running series.

Within the cadre of esteemed, award-winning authors, there’s a subset that I tend to think of as covertly prolific. Oftentimes, they publish somewhere between a handful and a dozen novels throughout their careers, which by the standards of mainstream literature would be commendable but within science fiction doesn’t quicken anyone’s pulse.

[Click for images with more conviction.]

|

|

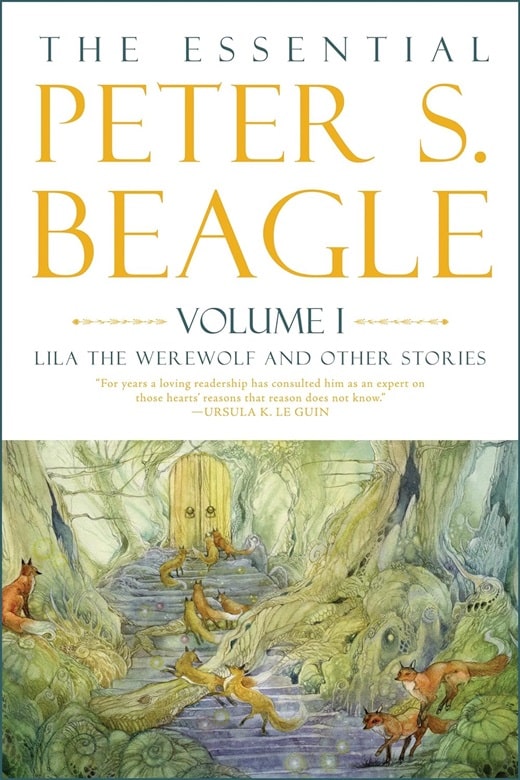

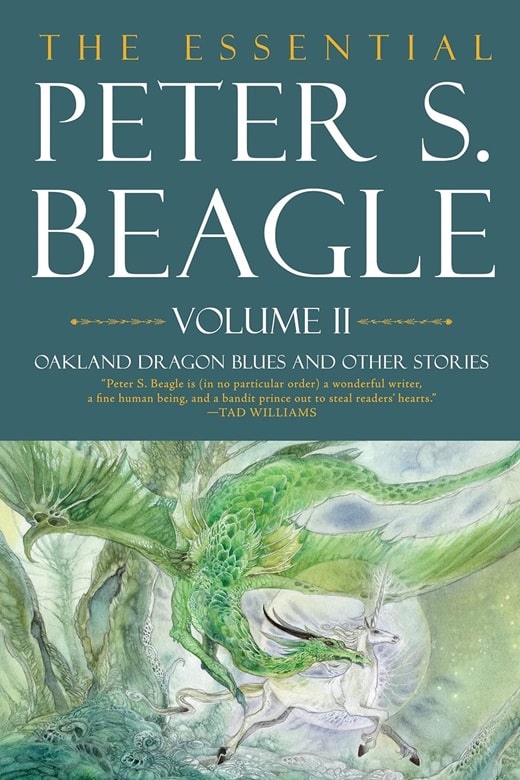

The Essential Peter S. Beagle (Tachyon Publications, May 16, 2023). Covers by Stephanie Law

Short fiction, by contrast, is where these writers marathon away, often publishing top-notch work at the rate of several stories per year, consistently, over many decades. Nina Kiriki Hoffman, Robert Reed, Nina Allan, Aliette de Bodard, and Sarah Pinsker are several examples that come to mind. Within the list of Grand Masters, I’d say that Peter S. Beagle, whose two-volume The Essential Peter S. Beagle was recently released by Tachyon Publications, merits inclusion amongst the sneakily industrious.

Enter Michael Swanwick.

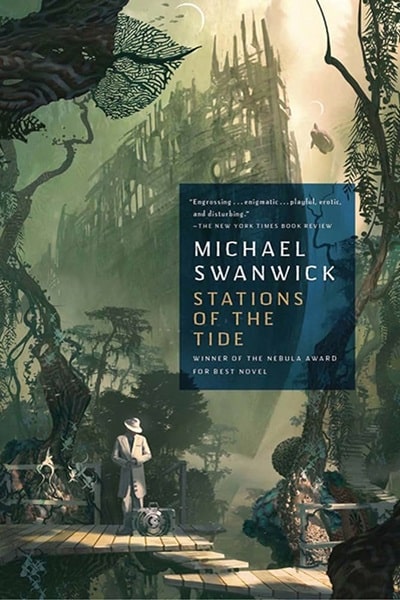

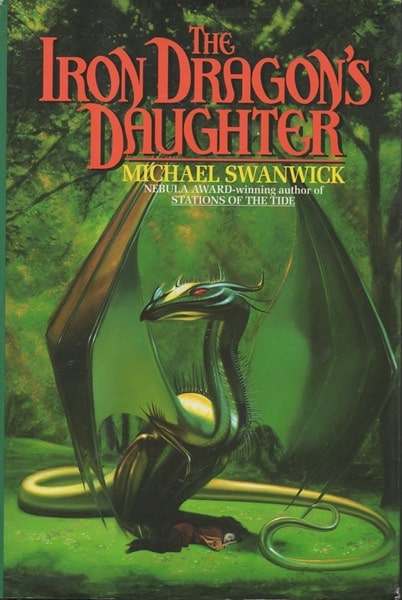

He has published some very fine novels indeed — Stations of the Tide (1991), The Iron Dragon’s Daughter (1993), Bones of the Earth (2002), Chasing the Phoenix (2015), and several others — but they tend to be spaced out by a period of years. And yet, in tandem, he has also published one dazzling collection of short stories after another, in fact more than novels.

Swanwick started publishing short fiction in 1980 and has kept at it at a staggering pace, with the story “The Star-Bear” out on Tor.com just several months ago. Short fiction doesn’t tend to have the commercial outreach that novels do, and a number of Swanwick story collections have been issued by boutique publishers, so his name has perhaps not circulated through popular consciousness as widely as it should.

|

|

|

Stations of the Tide (Orb, February 2001), The Iron Dragon’s Daughter (AvoNova, January 1994),

and Chasing the Phoenix (Tor, August 11, 2015). Covers by Thom Tenery, Dorian Vallejo, Stephan Martiniere

When I set about interviewing Michael about his body of work, I knew that my focus would be his short fiction. As I shared news of this project with various friends and colleagues, I was asked with genuine curiosity, more than once, what compelled me to choose Swanwick as opposed to several other possible candidates. “Have you read his short stories?” I asked.

I realized that beneath the question “Why Swanwick?” lay the question “Why do you want to spend a couple of years steeped in short fiction when you could be reading novels instead?” After all, the initial “core” reading list I assembled for Michael and I to discuss numbered around a hundred stories. And of course he wasn’t going to stop writing new fiction while we discussed his old work, so by the time we reached my original endpoint there were at least a dozen new stories waiting for us to delve into. I mock protested to Michael about this on one of our video calls, which seemed to please him.

To give a sense of why I think short stories are of vital importance I’m going to invoke the electromagnetic spectrum. We divide the EM spectrum into different ranges based on the wavelength and frequency of the radiation on hand; at one end, we have radio waves, which are characterized by long wavelengths, and on the opposite end of the spectrum, Gamma rays, which have very short wavelengths.

Now, consider the continuum of narrative length. Radio waves, I think, are like novels: they can conquer great distances, and can be used to investigate faraway domains through elaborate imaginative feats. Novellas, by contrast, are akin to visible light; the tasteful novella is crystal clarity, offering wonders to last a lifetime in a shorter burst. Continuing on, poems are like the Gamma rays I mentioned, highly charged with energy, dense with meaning. And short stories, somewhere between novellas and poetry, are like X-rays. They allow us to peer through the structure of ordinary reality, opening up richer realms. Also, for the most part, they can be enjoyed in about the same time it takes to get a conventional X-ray.

Michael Swanwick. Photo by Kyle Cassidy

Getting to pick Michael’s brain about his numerous tales was incredibly rewarding. In a way, my natural gravitation to his shorter works was justified a posterioi when, nearing the end of our project, Michael said, “I believe in the beauty of short fiction, in the purity of it, and the fact that it can do things that long fiction simply cannot.” Amen.

One other thing Michael said bears citing: “A fact is a unit of truth, but a story is a unit of conviction.” Michael Swanwick’s stories are brilliantly crafted and contain endlessly fascinating characters and ideas.

Yet beyond that, they are full of stances: philosophical, spiritual, humanistic — and moral. X-ray exposure is typically measured in units of roentgen; in the case of Michael’s artistic X-rays, our units are conviction. Stories like “Ginungagap” (1980), “The Changeling’s Tale” (1994), “The Dead” (1996), “Hello, Said the Stick” (2002), “Urdumheim” (2007), “The She-Wolf’s Hidden Grin” (2013), “Cloud” (2019), and countless others penetrate our deepest impulses and temptations, foibles and pretenses, longings and regrets, as well as the profoundly beautiful and ultimately ineffable aspects of being alive.

Quietly but assiduously, Michael Swanwick has spent the last forty years developing a literary radiograph of our souls.

Alvaro Zinos-Amaro is a Hugo- and Locus-award finalist who has published over fifty stories and one hundred essays, reviews, and interviews in professional markets. Traveler of Worlds: Conversations with Robert Silverberg was published in 2016 to critical acclaim. Being Michael Swanwick is Alvaro’s second book of interviews. His debut novel, Equimedian, is forthcoming in 2024.

Congratulations on the publication of “Being Michael Swanwick!” The term “covertly prolific” is a delicious way to describe a number of authors; hopefully it will catch on. The backstory of this work, the quotations, and the other curtain-whisking tidbits in this article make both the book and its subject sound intriguing, to the point where a pre-Christmas trip to the bookstore that risks undoing months of discipline seems worthwhile.

It was also pleasant to see NKH referenced for something other than her magical realism/proto-urban fantasy.

Months of discipline to stay away from bookstores? Even the thought makes me weak. I had to go have a bit of a lie down.

XD It’s not fun, but neither is getting yelled at by family-members who see one’s fingers twitch toward a book that they think should be left alone for potential gifting.

…And the January book run is cathartic for everything but my groaning shelves, so there’s that, too.

Thank you so much for the lovely words! Let’s sneak in the phrase whenever it’s apt 🙂

If I ever achieve weeks, let alone months, of book-buying restraint, I’ll let you know. For now, let our shelves groan in resigned unison.

I loved BEING MICHAEL SWANWICK, and I agree that he is “covertly prolific” in that sense — nice term. (One might cite Robert Reed as another “covertly prolific” writer, though maybe less covert! Still — so many short stories. and not that many novels.)

But I’ve been reading some great SF writers — including a Grand Master, and one should should have been — who really weren’t that prolific at all. I’m thinking of Alfred Bester, and of Joanna Russ. (Not to mention Ted Chiang!) So proflicity may be in the SF DNA — but there are still mutants! 🙂