Donald A. Wollheim and the Death of the Future

|

|

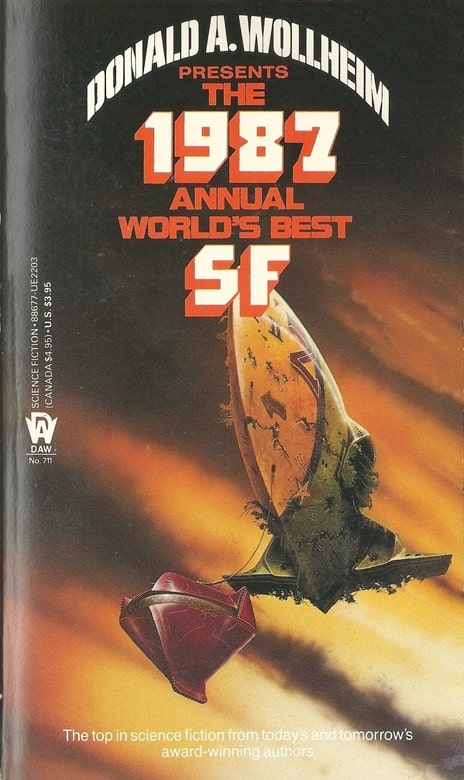

The 1987 World’s Best SF (DAW Books, June 1987). Cover by Tony Roberts

I’ve been reading a lot of older science fiction recently, though not in a very organized fashion. I pulled Wollheim’s 1987 World’s Best SF off the shelf this morning to read Pat Cadigan’s cyberpunk Classic “Pretty Boy Crossover,” which I saw on the table of contents of Jared Shurin’s The Big Book of Cyberpunk. I prefer to the read the original, when I can.

Of course I got distracted by the rest of the book, which contains plenty of classic tales, including Lucius Shepard’s Nebula award-winning 87-page novella “R & R,” Roger Zelazny’s Hugo-winning “Permafrost,” Howard Waldrop’s Nebula nominee “The Lions Are Asleep This Night,” and a few delightful surprises. I wrote it up as a Vintage Treasure back in April.

But the thing that really commanded my attention this time was Wollheim’s curmudgeonly introduction, which contains the most uncharitable description of the Challenger disaster and crew I’ve ever read, and his wildly off-base assessment of this new-fanged cyberpunk stuff, which he asserts “has something to do with computers and their programming and possibly — considering the derogatory term “punk” — with snubbing accepted traditions.”

Today it reads more like a eulogy for the bright and shiny future science fiction once promised than an introduction by one of the founding fathers of the genre.

[Click the images for cyberpunk versions.]

|

|

|

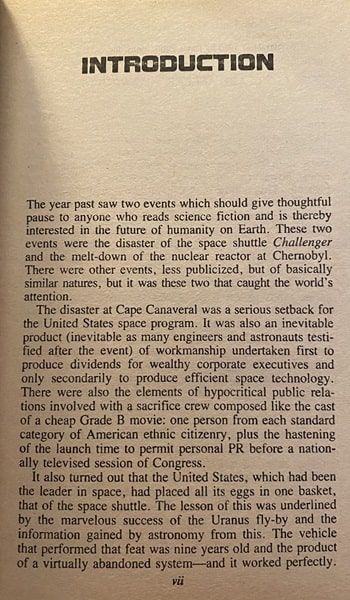

Donald A. Wollheim’s introduction to The 1987 World’s Best SF

This is the 23rd volume of World’s Best SF, and Wollheim’s 23rd introduction, and by this point he doesn’t mince words. The first thing on his mind is the horrific fate of the Space Shuttle Challenger, which exploded 73 seconds after lift off on January 28, 1986, killing all seven crew members. Like a lot of people of a certain age, I remember exactly where I was when I heard the news (at the Fandom II game store near the campus of the University of Ottawa), and the brief pall it cast over the future of the entire US space program.

Wollheim seemed to take this disaster personally, like many space enthusiasts and science fiction fans. By the middle of the second paragraph, he’s ready to lay the blame firmly at the feet of both capitalism and diversity.

The disaster at Cape Canaveral was a serious setback for the United States space program. It was also an inevitable product… of workmanship undertaken first to produce dividends for wealthy corporate executives… [and] a sacrifice crew composed like the cast of a cheap Grade B movie: one person from each standard category of American ethnic citizenry.

This is appalling. The clear implication that, because they were ethnic, the dead crew of the Challenger were somehow less qualified and perhaps to blame for the disaster is racist and grotesque.

The remainder of the introduction is also problematic, chiefly in its darkly nihilist overtones. The joint disasters of Challenger and Chernobyl, and the subsequent public deaths of two of science fiction’s fondest dreams, safe space travel and limitless nuclear energy, clearly hit Wollheim hard. It all has echoes of the last time a bright science fictional dream died a violent death, in 30-point font on the front page, at Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

What sort of world do we find ourselves in during the last fourteen years of the Twentieth Century? Does it make sense? Is all this a form of species suicide?…

It is not surprising that science fiction is booming. It deals with the future and this is the secret concern of anyone alive since 1945.

It’s a sour, gloomy, and mean spirited Introduction all around, and I suggest you just skip it.

|

|

|

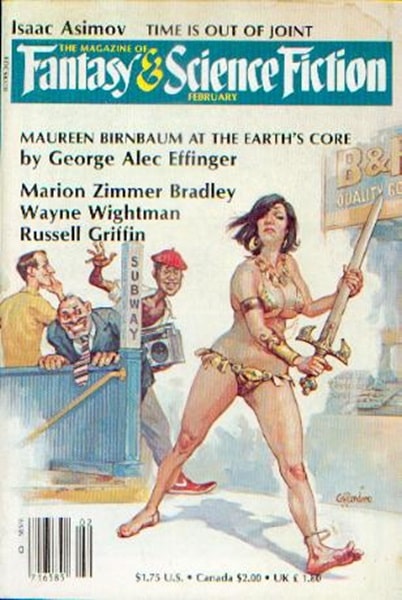

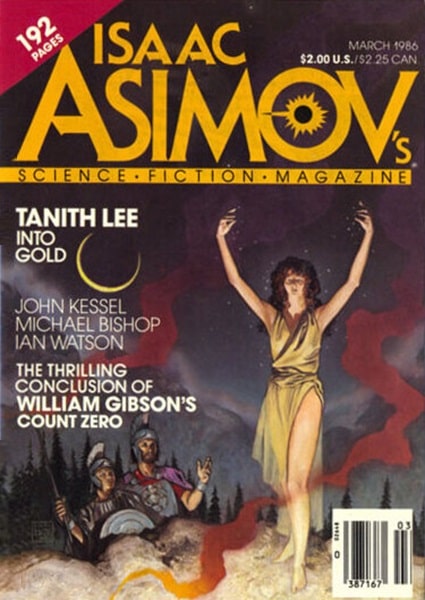

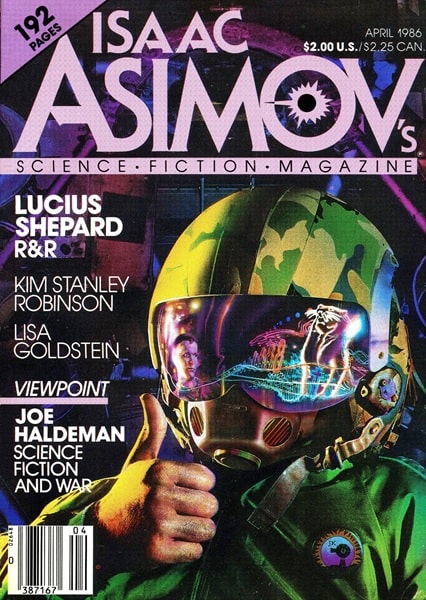

Some of the magazines that originally published these stories: The Magazine of Fantasy

& Science Fiction, February 1986 and Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine,

March and April 1986. Covers by G. P. Lendino, Carl Lundgren, and J. K. Potter

Fortunately the stories themselves make up for Wollheim’s horrible introduction.

Some of the credit for that has to go to his co-editor, Arthur W. Saha, Wollheim’s assistant at DAW since 1972. Saha — who’s famous for having coined the word “Trekkie” in a 1967 TV Guide interview — was a member of the Futurians, alongside Frederik Pohl, Isaac Asimov, and Wollheim himself. After Lin Carter died he became editor of The Year’s Best Fantasy Stories (from 1981-88), DAW’s other annual Year’s Best series, and he was inducted into the First Fandom Hall of Fame for his contributions to science fiction in 1992, seven years before he died.

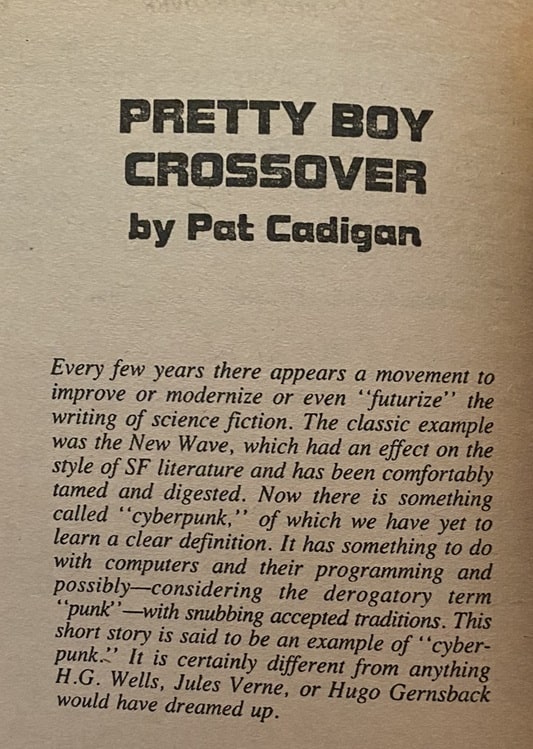

Unfortunately, Wollheim’s individual introductions for each story also hit the occasional sour note. His intro for Cadigan’s “Pretty Boy Crossover” — a formative cyberpunk take — sounds like he has absolutely no idea what cyberpunk it all about, and even less interest in learning.

Wollheim’s introduction to Pat Cadigan’s “Pretty Boy Crossover”

Though he may have lost his faith in Science Fiction, and perhaps even his hope in the future, Wollheim can still pick terrific stories.

The 1987 World’s Best SF placed seventh in the 1987 Locus Award for Best Anthology (Dozois’ The Year’s Best Science Fiction: Fourth Annual Collection was first, followed by Jack Dann’s In the Field of Fire and Terry Carr’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year #16).

I discussed the rest of the book in more detail in my April Vintage Treasures post, but in case you’re too lazy to click the link, here’s the complete Table of Contents.

Introduction by Donald A. Wollheim

“Permafrost” by Roger Zelazny (Omni, April 1986) — Nebula and Locus Award nominee, Hugo Award winner

“Timerider” by Doris Egan (Amazing Stories, March 1986)

“Pretty Boy Crossover” by Pat Cadigan (Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, January 1986) — Nebula Nominee, SF Chronicle Award winner

“R & R” Lucius Shepard (Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, April 1986) — Hugo nominee, Locus and Nebula Award winner

“Lo, How an Oak E’er Blooming” by Suzette Haden Elgin (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, February 1986)

“Dream in a Bottle” by Jerry Meredith and D. E. Smirl (L. Ron Hubbard Presents Writers of the Future, Volume II, March 1986)

“Into Gold” by Tanith Lee (Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, March 1986)

“The Lions Are Asleep This Night” by Howard Waldrop (Omni, August 1986) — Nebula nominee

“Against Babylon” Robert Silverberg (Omni, May 1986)

“Strangers on Paradise” by Damon Knight (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, April 1986)

The book has been out of print for 36 years and there is no digital edition, but copies are plentiful and inexpensive on sites like eBay.

I am not sure that Mr. Wollheim is blaming the crew of the Challenger for being diverse so much as responding to the wider sense of shock that hit due to that diversity, particularly the many schoolchildren who were drawn to watch the launch as a result of seeing the first schoolteacher, Christa McAuliffe, flying into space. That loss of innocence was keenly felt.

On the other hand, I have to agree that the intro blurb for Ms. Cadigan’s story is a case of sour grapes. Not much of a plug for a “best story”, is it? Ouch.

No, it’s not much of a blurb at all. I rather get the impression it’s something Wollheim pounded out on his typewriter after Arthur Saha handed him “Pretty Boy Crossover” for the first time.

Overall, Wollheim’s comments are a good example of what we’d now call “grumpy old man shouts at clouds”, and the space shuttle comments are crass and unpleasant.

The grumpy comments, at least, are understandable. He was indeed old – born 1914, and died in 1990 – and I’ve no idea what his health was like at this stage, which can of course affect temperament . Wollheim had seen the genre he loved go through multiple generations of change, of which cyberpunk was only the latest; I don’t think he’d been much of an enthusiast of New Wave in the 1960s, which had a much great impact at the time, yet he appears much more critical (or dismissive) of cyberpunk.

He’d hardly be the first enthusiast of any form of literature – or art, or music, or film, or whatever – who, after decades of coping with the changes in their favoured interest, finally hit the wall with a “what is it with these blasted kids today and their crazy ……” reaction (You don’t even have to be that old; as a late-teens enthusiast in the early years of Punk Rock, I recall seeing that exact reaction in many people only a few years older than me). Add to all of these factors the obviously disillusionment of the “Challenger” and Chernobyl disasters, and Wollheim’s response is understandable, if not pretty.

We all age, and the opinions of most of us tend to ossify, but back then few of use had the ability to communicate those views to a mass audience. Perhaps unfortunately, we now do.

You are entirely correct. Wollheim is entitled to his grumpy opinions, and by 1987, given the extent of his own extraordinary contributions to the field, I’m sure he was granted a great deal of latitude to express them.

I guess I still find it ironic that a man who tirelessly championed science fiction — a literature that celebrates the new — was so resistant to new things at the end of his career. Harlan Ellison, who had nothing but scorn for word processors and the Internet, was very much the same. I suppose it happens to us all eventually.

It’s possible that he was being a bit facetious, in his reference to cyberpunk… an attempt at a joke that didn’t quite land, perhaps (possibly because he didn’t really have anything much else to say about it?!). But yeah, it’s not the greatest introduction that he could have come up with, surely!

The book has been out of print for 10 years longer than the title suggests? It’s amazing that DAW was able to put together a book that has stories that weren’t even written yet!

Ha! Right you are. I’ve corrected my last paragraph to note that the books has been out of print for 36 years, not 46.

But it would have been more intriguing if your last sentence were correct. 🙂

You also quote his reference to cyberpunk snubbing older approaches to sf (which some of its proponents did do) as “subbing” them…which can have some implications re certain uses of “punk”, unfortunately (at least in the context of this article).

Todd,

Whoops! Right you are. It’s one thing to fat-finger my own thoughts… but I should at least get the quotes right!

Thanks for the catch.

Also, I believe Art Saha was in the later version of the Futurians, after the heavily fan-folklore days of the ’40s…this biography of Saha seems to suggest as much: https://fanac.org/conpubs/Lunacon/Lunacon%2043/Lunacon%202000%20Program%20Book.pdf#page=41

Todd,

Great bit of research (either that, or you have a fantastic memory!). This article states:

“After the war… he became involved in New York City science fiction fandom… He was active in the Lunarians for many years.”

That seems to imply he could have been involved in the Futurians from about 1945. Do you read it differently?

He could’ve been, but I don’t remember any mention of him in Knight’s THE FUTURIANS nor the other memoirs of the Original Futurians, which seemed to pretty much be atomized after a number of them went into WW2 service…and, by the time these accounts were published, Saha was already an editor, otherwise had been a figure in fandom, and even his daughter was already a (somewhat controversial/problematic) former(?) figure in the fannish community. I’m more raising the question than providing a final answer…