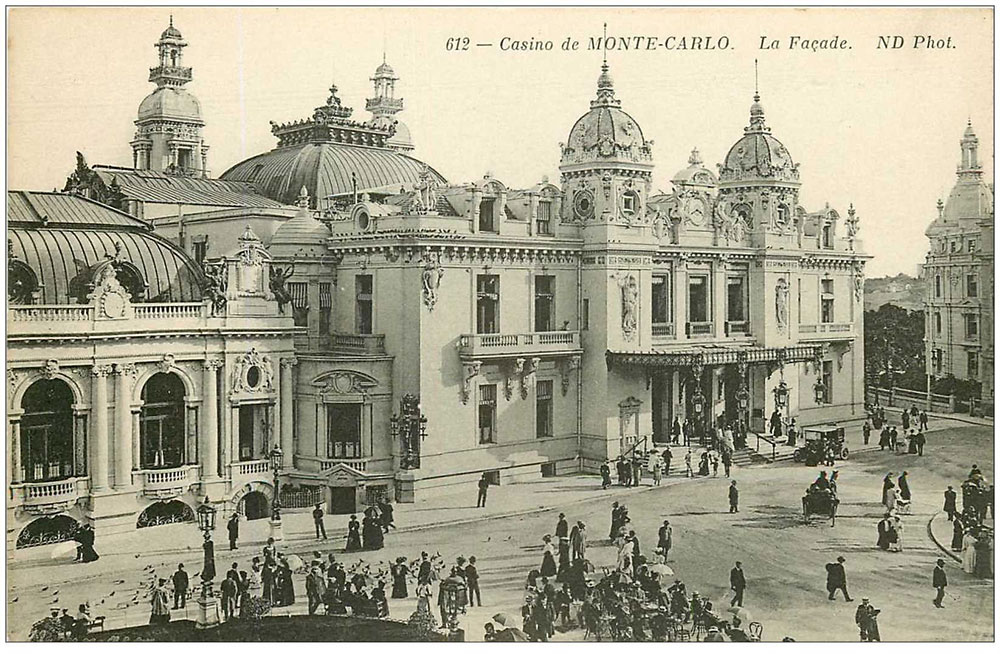

The Sorcerer and the Novelist: W. Somerset Maugham’s The Magician

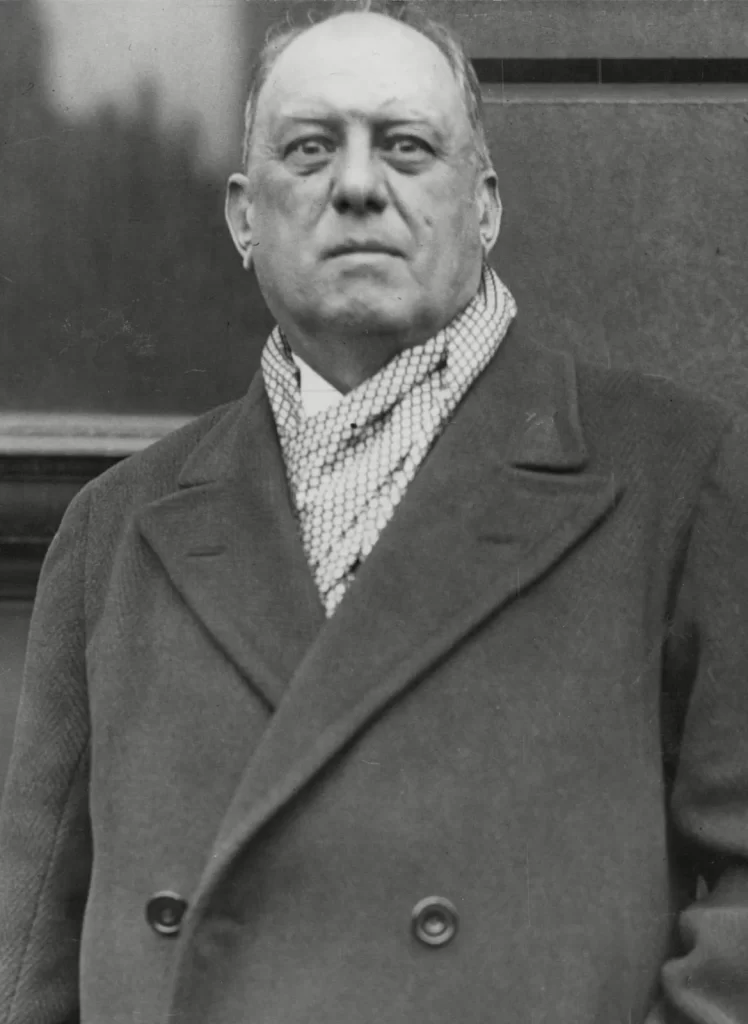

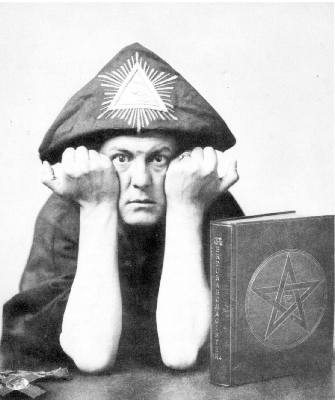

Aleister Crowley

Aleister Crowley, poet, mountaineer, religious mystic and self-proclaimed prophet, member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, drug addict, braggart, sexual adventurer, the self-named “Beast 666” and, according to the popular press, “The Wickedest Man in the World,” was one of the most notorious and controversial figures of his era and remains so even today, three quarters of a century after his death.

W. Somerset Maugham, physician, world-traveler, wildly successful playwright (at one time he had four plays appearing in London’s West End theaters simultaneously) and sometime British secret agent, prolific short story writer and novelist, author of such acclaimed works as Of Human Bondage, The Moon and Sixpence, and The Razor’s Edge, was one of the major literary figures of the twentieth century.

These two very different men may seem an unlikely pair, but Maugham met Crowley in Paris in 1905 and (like virtually everyone who encountered the man) was strongly impressed by him. In Maugham’s case the impression was a highly negative one, though he did concede that the occultist had some unique qualities, so much so that he made a thinly-disguised Crowley the central figure in his 1907 novel, The Magician.

W. Somerset Maugham

In a preface that Maugham wrote when the book was republished decades later, he recounted his acquaintance with Aleister Crowley:

I took an immediate dislike to him, but he interested and amused me. He was a great talker and he talked uncommonly well. In early youth, I was told, he was extremely handsome, but when I knew him he had put on weight, and his hair was thinning. He had fine eyes and a way, whether natural or acquired I do not know, of so focusing them that, when he looked at you, he seemed to look behind you… He was a liar and unbecomingly boastful, but the odd thing was that he had actually done some of the things he boasted of.

Maugham’s most telling observation is the same one that many who knew Crowley made: “He was a fake, but not entirely a fake.”

Maugham wrote The Magician shortly before he produced his greatest work (Of Human Bondage was his next novel) and he thought of it as a potboiler, something that could make him a bit of money while he gathered his energies for more important work. Outré fictions were all the rage during those Fin-de-Siècle years, and the success of weird thrillers like Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), Richard Marsh’s The Beetle (1897), and Bram Stoker’s The Jewel of Seven Stars (1903) demonstrated the public’s appetite for such tales. Maugham additionally cited the French writer J.K. Huysmans’ 1891 novel of decadence and Devil-worship, Là Bas (Down There) as an influence.

The germ of the novel lies in an incident Maugham had heard about involving Crowley and a woman named Rose Kelly. In 1903 Rose’s brother Gerald introduced her to Crowley, and she found him so overwhelming that she married him a scant two weeks afterwards. The match did not meet with the approval of Rose’s family, especially Gerald, who was so violently opposed to the marriage that on first encountering Crowley after the wedding, he physically attacked him. The marriage lasted only a few years, leaving Rose an alcoholic ruin, and Gerald Kelly raged against Crowley for the rest of his life. (In fact, it was Gerald Kelly who told Maugham the story.)

The Magician centers around Oliver Haddo, a man possessing most of the physical attributes and repulsive and magnetic character traits of the Crowley that Maugham knew, while Rose Kelly becomes Margaret Dauncey, a beautiful, hopeful, unsullied young woman of nineteen. (Rose Kelly was a thirty-year-old widow when she met Crowley.)

The novel’s other significant characters are Margaret’s fiancée, the physician Arthur Burden, as bluff, blunt, and manly a sort as any Edwardian could wish for (he has a passion for golf, for goodness’ sake), Arthur’s friend Doctor Porhoët, an elderly scholar of the occult who is learned in the ways of the exotic East, and Margaret’s best friend, Susie Boyd, sharp-witted, perceptive, loyal and plain looking (and silently in love with Arthur herself).

The story begins in Paris, where Margaret and Susie are living while Margaret studies art. Doctor Porhoët is in the city too, and Arthur arrives to visit both his mentor and his betrothed. As he and his old friend stroll through the gardens and along the boulevards, they pass “a big, stout fellow, showily dressed in a check suit” who silently salutes Porhoët and passes on. When Arthur asks who the man is, the doctor tells him that his name is Oliver Haddo and that he met him in the library while researching his latest book on the occult, a subject on which Haddo turned out to be an expert. He also tells Arthur that Haddo’s interest in such matters extends beyond the merely scholarly; he believes himself to have genuine magical powers, a notion at which Arthur scoffs.

That evening, when Arthur and Doctor Porhoët meet the women at a restaurant for dinner, they see the same man. It is not long before he has attached himself to their party and from that moment on, Haddo increasingly inserts himself into their lives.

The group’s response to the self-styled magician is mixed. Arthur instantly dislikes and distrusts him, a response Haddo reciprocates (while still maintaining ironic good manners), while Susie finds him fascinating and amusing. Margaret has the strongest response; whenever she is in Haddo’s presence, she experiences a visceral, almost physical revulsion. (“I never met a man who filled me with such loathing”, she says soon after their first meeting.)

It is not long before the catastrophe occurs. Susie makes the mistake of inviting Haddo to tea at the studio where she and Margaret live. Arthur and Doctor Porhoët are present as well, and during the conversation, Haddo, “a peculiar arrogance flashing in his shining eyes”, discourses on his philosophy of power:

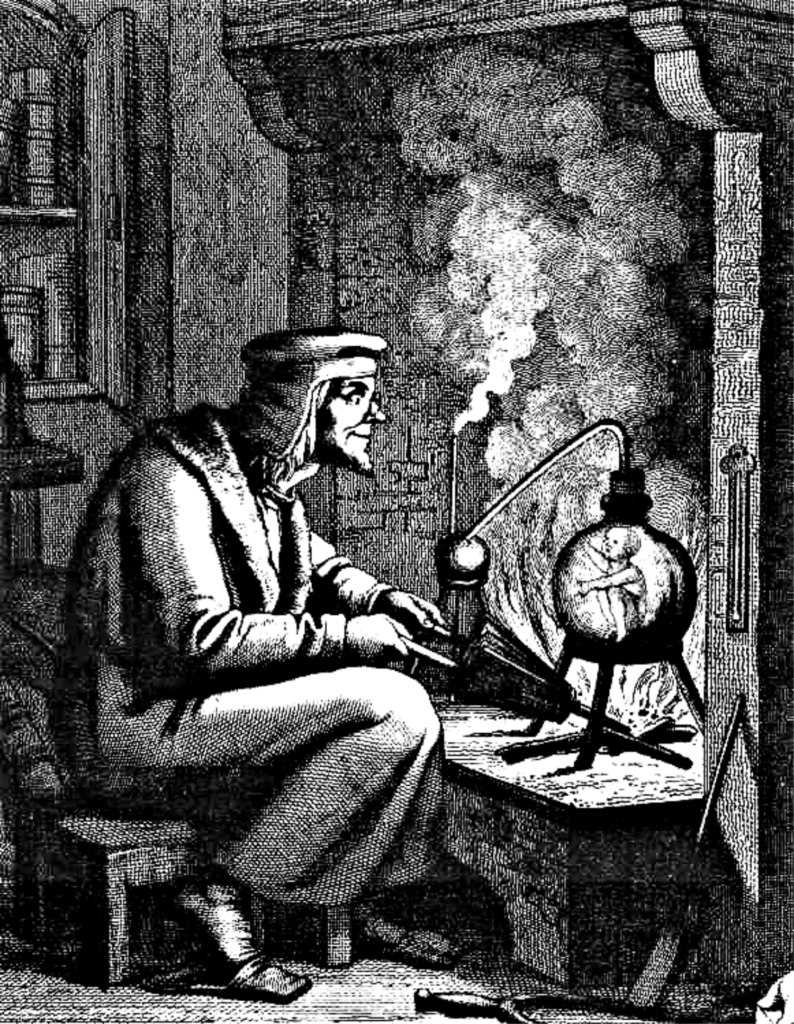

And what else is it that men seek in life but power? If they want money, it is but for the power that attends it, and it is power again that they strive for in all the knowledge they acquire. Fools and sots aim at happiness, but men aim only at power. The magus, the sorcerer, the alchemist, are seized with fascination of the unknown; and they desire a greatness that is inaccessible to mankind. They think by the science they study so patiently, by endurance and strength, by force of will and by imagination, for these are the great weapons of the magician, they may achieve at last a power with which they can face the God of Heaven Himself.

He further rhapsodizes on the possibility of creating, by magical means, homunculi, artificial life forms that, Haddo asserts, were successfully “generated” by the alchemists of old. When Arthur asks what use such unnatural creatures would be, Haddo declares that he is less interested in the homunculi themselves than in the sensations their creation would excite in the one who made them. “Sometimes my mind is verily haunted by the desire to see a lifeless substance move under my spells, by the desire to be as God.”

All this time, Margaret’s terrier, Copper, has grown more and more agitated until finally it leaps at the magician and bites him in the hand. Haddo throws the dog off and viciously kicks it. Arthur, in a rage at the man’s cruelty, flies at Haddo and smashes him in the face, and when the magician collapses to the floor, Arthur, his loathing overflowing, continues to batter and kick Haddo, who all this time offers no resistance. His anger spent, Arthur turns to comfort the weeping Margaret, and as he does so, Susie watches Haddo rise to his feet, his face “hideously deformed” by an expression of “satanic hatred.” Then, unexpectedly, Haddo makes a clear effort of will, and banishing the malignant look, meekly apologizes to both Margaret and Arthur and leaves the house.

A few days later, Margaret receives a letter from an old friend who will be arriving in Paris and has written to arrange a meeting. The letter is not from Margaret’s friend, however. It is a ruse to get her out of her studio at a specific time; Oliver Haddo’s contrition was, as they all suspected, a sham, and the magician is now working to exact his vengeance on Arthur. (And revenge is not his only aim; he has another, even darker purpose that will become clear only later.)

As soon as Margaret leaves her home to keep her appointment with her friend (as she thinks), Oliver Haddo passes by and almost instantly collapses in the street, apparently in extreme distress. Margaret’s compassion overcomes her aversion, and she helps Haddo into her studio, where he seems to recover after taking some medication that he carries for “a disease of the heart.”

Alone with Margaret (for Susie has also been lured away), Haddo exerts all of his power, the hypnotic power of his voice, of his eyes, of his personality, of his words, and the supernatural power of his magical knowledge (once Margaret has lost her ability to resist, he uses his power to show her mystical, enthralling, appalling — and corrupting — visions), and when an hour has passed, Margaret Dauncey is entirely in the power of the satanic Oliver Haddo. She is doomed.

Haddo leaves and Margaret resumes her normal routine, but as each day passes her desire to desert her friends and go to the magician increases until it is almost unbearable. She continues to show her old face to Arthur and Susie even as she feels the self that loves them being inexorably replaced, day by day, with a new self, a Margaret that is filled with hatred and contempt for her friends, that delights in spitefully deceiving them. Some part of her is terrified and sickened by this change, but in the end she cannot resist it. It is not long before Margaret has fled her home to marry Oliver Haddo.

A shattered Arthur returns to England to lose himself in his work, while Susie occupies herself with travel. In Monte Carlo she glimpses the Haddos gambling in the casino, where they are winning fabulous sums. Margaret looks to her less like a person than a puppet, a doll with a “curiously vicious look, which suggested that somehow she saw literally with Oliver’s eyes.” Susie also hears rumors that even after six months the marriage has not been consummated, perhaps because, like the wizards of old, Haddo believes in the magical potency of virginity and means to make use of that power.

Both Susie and the Haddos eventually return to England, and over the next several months Susie, Arthur, and Doctor Porhoët meet and discuss courses of action, especially since Susie is now convinced that the magician’s control over Margaret must be supernatural in nature. (Arthur, ever the rationalist, still has trouble believing such a thing.) Arthur even manages to see Margaret three times, once by chance at a dinner party (where Haddo greets him with sadistic glee), and two more times without her husband present — once at a hotel where she and Haddo are staying and where she seems to want to renounce her marriage but can’t summon the will to do it (though she briefly leaves with Arthur, she soon returns to Haddo), and a final time at Skene, Haddo’s ancestral home near the village of Venning. There Margaret confesses that she lives in constant terror, believing that her husband will soon murder her as part of some magical ritual or experiment, but again, she doesn’t have the power to escape and save herself.

Shortly after this final meeting, while consulting Doctor Porhoët back in Paris, Arthur is suddenly stricken by the certainty that something terrible has happened to Margaret. Arthur and Doctor Porhoët rush back to England. Once there, they connect with Susie and the three of them head for Skene… where they are told by an innkeeper that Margaret is dead, having suffered a heart attack just a day or two before.

The local doctor who signed the death certificate verifies a heart attack as the cause of death, and not believing the physician or his story, the friends confront Haddo at his home, “a fine old building in the Elizabethan style.” He speaks to them with malicious courtesy, repeating the tale of a heart attack before haughtily dismissing them.

Stymied for lack of physical proof, the group decides on a radical step. Arthur the one-time skeptic convinces Doctor Porhoët to use his occult knowledge to raise Margaret’s ghost; they will find out exactly what Haddo did from his victim herself.

Don’t Try This at Home — Professional Ghost Summoners on a Closed Course

Don’t Try This at Home — Professional Ghost Summoners on a Closed Course

For the summoning, they choose the last place Arthur saw Margaret alive — by a stone bench on a wooded part of Haddo’s property, where they had their final conversation. On a cloudy, starless night, Arthur, Susie, and Doctor Porhoët assemble in this bleak spot for the “experiment,” and the scholar’s efforts are rewarded with success. At first, “they heard with a curious distinctness the sound of a woman weeping… the sobbing of a woman who had lost all hope, the sobbing of a woman terrified.” And then:

In a moment, notwithstanding the heavy darkness of the starless night, Arthur saw her. She was seated on the stone bench as when last he had spoken with her. In her anguish she sought not to hide her face. She looked at the ground, and the tears fell down her cheeks. Her bosom heaved with the pain of her weeping.

Then Arthur knew that all his suspicions were justified.

Knowing that Margaret was murdered does the group little good, however, as their proof is not the kind that can be presented in court. But even if Haddo is legally untouchable, Arthur is determined not to leave the vicinity until he has killed him — but how to get at him? Days fruitlessly pass until one night, as Arthur, Susie, and Doctor Porhoët talk over the situation at the local inn, the lights in the room suddenly go out and Arthur finds himself fighting for his life in the darkness; Haddo, divining Arthur’s intentions, has used magical means to enter the room and launch a pre-emptive attack. The others sit paralyzed and helpless during the desperate struggle.

Surprise and his powerful build give Haddo an initial advantage, but Arthur’s rage and hatred, so long unable to touch his tormentor, give him the strength to finally win out. He is able to gain enough leverage to break Haddo’s arm, and then, savoring the terror he can now sense in his weakening opponent, Arthur strangles the magician to death. Of course, when Doctor Porhoët manages to strike a match and they look around the room, there is no Haddo, dead or alive. He has vanished.

Despite this disappearing act, Arthur is certain that Haddo is dead, and he immediately heads for Skene, reluctantly followed by Susie and Porhoët. Breaking into the darkened house (the only lights showing are those in the attic), they explore the first three floors, which seem to be largely unused, and find nothing. But when they stand behind the locked door to the attic, they hear a strange sound coming from the other side, “a sort of gibber, hoarse and rapid” that fills them with “an icy terror because it was so weird and unnatural.”

Arthur breaks down the door and they find themselves in Haddo’s inner sanctum, the brilliantly lit, blazingly hot laboratory in which he was conducting his unholy experiments. They proceed in silence from room to room (the bizarre noise that they had heard from behind the door has stopped), each one filled with tables covered with electrical devices and containers of chemicals, and they see open books which the magician was apparently consulting, but there is no sign of Haddo himself.

Finally, in the last room, they arrive at the heart of the mystery: “a row of large glass vessels,” each one concealed by a white cloth. With mounting horror and nausea, they uncover each one in turn and see at last Haddo’s handiwork, the malformed, half-formed homunculi that were his supreme goal. All are ghastly, repellent — some have “faces” without a mouth, nose, or eyes; some have large heads upon tiny bodies, while some have two heads; one has four arms and four legs. Each one is a “caricature of humanity so shameful that one could hardly bear to look.” And all are alive.

At the final container, larger than the rest, even Arthur hesitates, but he steels himself and pulls away the cloth, and the instant the container is uncovered, its inhabitant bursts forth with the sounds that they had heard earlier, “a kind of raucous crying, hoarse yet shrill, uneven like the barking of a dog, and appalling.”

And now, they finally behold Haddo’s masterpiece, the thing that manifests the obscenity of his ambition and the nullity of his achievement:

It was mad with passion and beat against the glass walls of its prison with clenched fists. For the hands were human hands, and the body, though much larger, was of the shape of a new-born child. The creature must have stood about four feet high. The head was horribly misshapen. The skull was enormous, smooth and distended like that of a hydrocephalic, and the forehead protruded over the face hideously. The features were almost unformed, preternaturally small under the great, overhanging brow; and they had an expression of fiendish malignity.

The friends can only stand in stunned silence as the thing “shrieks senseless gibberish in its rage” and throws “its whole body madly against the glass walls” as it seeks to get at them. This repulsive creature “was the nearest that Oliver Haddo had come to the human form.” Arthur can only whisper, “Was it for these vile monstrosities that Margaret was sacrificed in all her loveliness?”

Kelly and Crowley, the Unhappy Couple

Kelly and Crowley, the Unhappy Couple

They receive no answer from Oliver Haddo; his corpse — which they discover behind a table — with its broken arm, bulging eyes, and livid, fear distorted face, is silent. What answer could the would-be god have given that could speak any more eloquently than his final creation?

There is nothing more to see, but as they leave this chamber of horrors, Arthur sends Susie and Doctor Porhoët ahead while he stays behind to take care of some final business. Shortly afterward, he rejoins them and as they walk back to their inn, they pause at the top of a hill. In the east, the sun is just beginning to rise, and looking back to the west, in the direction of Skene, they see a “deep red glow.” The house is burning; soon Oliver Haddo and all of his works will be nothing but ash. A fresh new day is dawning, cleansed of the magician and his evil, and in its light Susie and Arthur can glimpse a future in which they may be destined to be more than just friends.

The Magician is a peculiar book, a grotesque, shudder-pulp story filtered through Maugham’s ironic, psychologically acute sensibility and rendered in his precise, meticulous prose; the effect is that of a well-dressed, impeccably-mannered aristocrat leaning over and whispering a depraved anecdote in your ear. The clean-fingernailed style and the hair-raising subject matter spend a good deal of time jostling against each other, especially in the book’s sensational climax, and while this may keep The Magician from being completely successful, it does help make it a striking and memorable work, despite its sometimes uneasy mix of method and material. Ultimately, the book is perhaps most effective simply as a portrait of an extraordinary individual.

I do think it’s significant that the most powerful thing in the book is not the wild conclusion in the lab, but is instead the eerie, melancholy scene of the summoning of Margaret’s ghost; the contrast of the motionless, desolate, quietly weeping figure with the over-the-top pulp horrors of Haddo’s diabolic workshop couldn’t be greater, and it’s the more subdued scene that stays in the mind longer and imparts a real shiver, even in recollection. It’s a good indicator of which mode Maugham was more comfortable with.

In this Issue – W. Somerset Maugham!

In this Issue – W. Somerset Maugham!

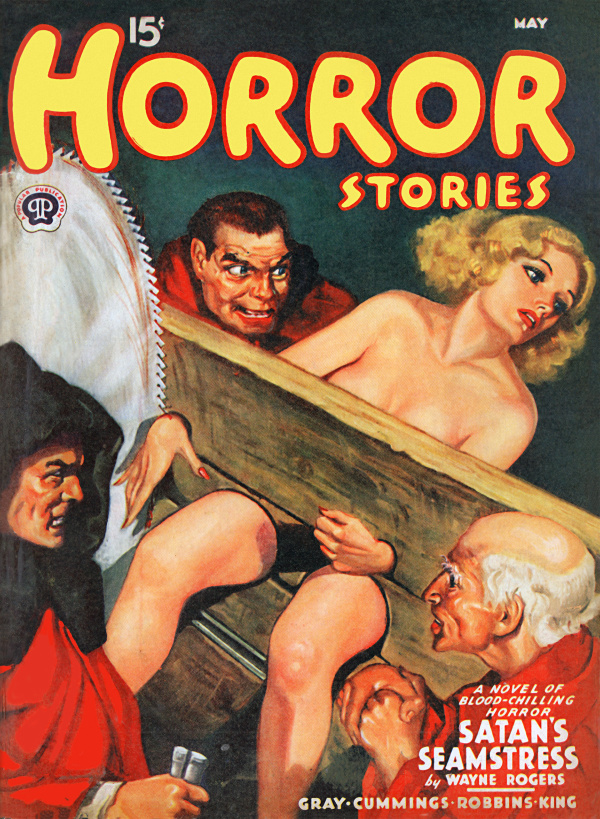

Maugham was an astute critic of his own work, and he was right — The Magician is a potboiler, but a potboiler with a difference. The blending of the lurid and the literary gives the story a flavor that’s unique, almost as if for some odd reason the highly cultured, well-bred Maugham had seen fit to write a garishly-lit shocker for a sleazy rag like Horror Stories, the sort of thoroughly disreputable yarn where leering, scarlet-cloaked acolytes use a buzz saw to threaten a helpless, unclothed damsel with dismemberment. Wholly successful or not, the combination is certainly not something you see every day.

This one hundred-and sixteen-year-old supernatural thriller is still worth reading for both sides of its somewhat schizophrenic personality… but that’s just my opinion. If you want a more authoritative recommendation for The Magician, here it is — Aleister Crowley liked it.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was Movie of the Week Madness: Satan’s School for Girls

Aleister Crowley seems to have been something of an influence on science fiction; both L. Ron Hubbard and Jack Parsons belonged to an American offshoot of the Golden Dawn that he influenced, and Robert Heinlein, who knew both men, alludes to Crowley’s Book of the Law in Stranger in a Strange Land—it’s one of the books that Valentine Michael Smith studies.

It’s interesting to learn of a literary work where he shows up. I’ve long supposed that Charles Williams’s first novel, War in Heaven, reflects his influence as well. Maugham’s The Magician sounds like a perfect work for a graphic novel version . . .

Thanks Thomas,

That was a rather cool article. The background research reminded me, is some respects, of the character Roderick Burgess from the Sandman. They say that character wasn’t based on Crowley in particular, though there are a lot of comparisons.

Looks like another book I’ll have to check out 🙂

I think it’s a worthwhile read, Andrew, and a quick one – a little less than 200 pages in my Penguin paperback.

I believe the bad guy in Casting of the Runes by M.R. James is also based on Crowley.

He was a fascinating figure in a sinister kind of way.

I’ve heard that too – it sounds like there might be enough stuff out there to do an anthology of fictional Crowleys!

He’s a key figure in Robert Anton Wilson’s Masks of the Illuminati, a historical fantasy where Albert Einstein and James Joyce team up to solve a mystery.

Interesting to note the corollaries with Trilby – especially the Parisian setting!

Interesting — I’ve never seen a picture of Crowley before, and I guess my mental image was always something more like, e.g., Alan Moore with the mighty black beard &c., not somebody who looks like just this guy.

Look, Crowley might have been sinister – evil, even. But he wasn’t crazy!

Sherlock Holmes meets Crowley in Guy Adams’ ‘The Breath of God.’

it’s one of the earlier books in Titan’s second Holmes series. The gothic/supernatural one.

Please tell me Holmes wins.

Interesting stuff! Thanks for this.

I remember reading somewhere that when Al “Beast 666” Crowley was a member of the Order of the Golden Dawn, the other members took a dislike to him and the last time he showed up William Butler Yeats kicked him downstairs. Those were the days of fighting poets.