Let’s Found a New Species: Odd John by Olaf Stapledon

|

|

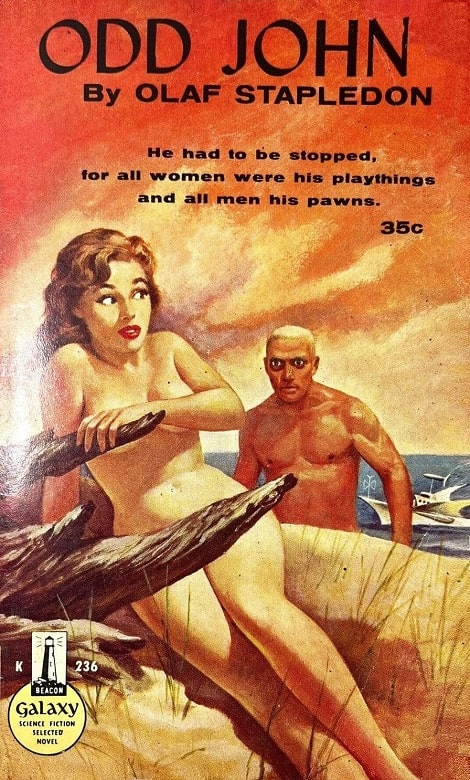

Odd John (Beacon/Galaxy Science Fiction Novel #36, 1959). Cover by Robert Stanley

In 1963, in the early issues of X-Men, Stan Lee introduced the expression Homo superior into superhero comics. But the name had a history before then: It was coined in 1935 by Olaf Stapledon, a British philosopher and science fiction writer, in Odd John, the fictional biography of a young superhuman.

The book that established Stapledon’s reputation, Last and First Men, published in 1930, was certainly science fiction but can’t be considered a novel in any normal sense; its two-billion-year history of humanity’s future is presented almost entirely as historical narrative, with only a few paragraphs of dialogue. But Odd John is definitely a novel, with a protagonist, John Wainwright, and a viewpoint character who is, by necessity, an unreliable narrator, as he himself points out on the first page of the story.

[Click the images for Odd versions.]

X-Men #1 by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby

(Marvel Comics, September 1963). Cover by Jack Kirby

Odd John is sometimes described as the first “superman” novel. In fact, Stapledon himself refers to an earlier one, J. D. Beresford’s The Hampdenshire Wonder, published in 1911. But Beresford’s story is mostly light entertainment. Stapledon made a real effort to treat the idea of the superhuman seriously.

Stapledon relies on an actual biological theory, though one that’s no longer generally accepted: Hugo de Vries’s mutation theory, proposed in 1901, according to which new species originate all at once in genetic changes that produce radically different offspring. Later biologists jokingly called this the “let’s found a new species, dear” theory — but that’s actually Stapledon’s plot: his protagonist, John Wainwright, makes an effort to find other superhumans and bring them together in an isolated community.

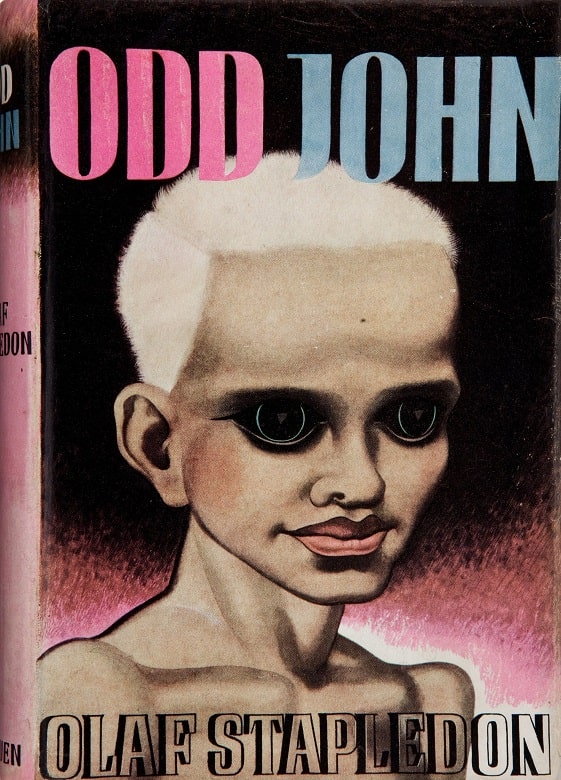

What is Stapledon’s Homo superior like? They all have certain physical traits in common, which generally fit speculations about what “evolutionary advanced” human beings might look like: large skulls with scanty hair, big sinewy hands, and enormous eyes. They’re intellectually brilliant, able to achieve scientific advances such as atomic energy and ectogenesis in a few years.

|

|

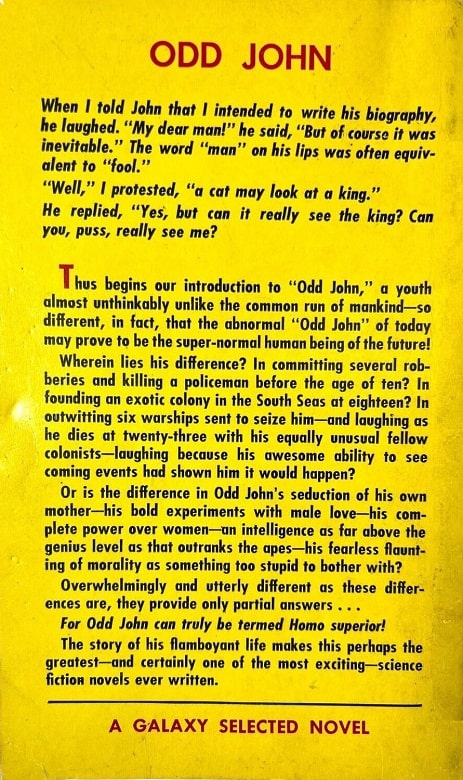

Odd John (Berkley Medallion, August 1965). Cover by Richard Powers

But it’s perhaps most important that they have a distinctive spiritual quality, one perhaps best captured in John’s own distinctive laugh, a peculiar sound like the crackle that precedes a peal of thunder, one most likely to be heard when John confronts pain or failure, in which the human narrator can see no imaginable cause for laughter.

But perhaps Stapledon, more sophisticated than his narrator, is thinking of what Nietzsche, who coined the word “superman,” called amor fati, the triumphant acceptance of necessity. The unusual talents, the grotesquerie, and the inhuman viewpoint also might suggest folkloric ideas of “the fair folk” and especially of the unseelie; an earlier era might have taken John as a changeling.

Nietzsche’s superman comes from an older idea, not biological but ethical: the man whose greater destiny justifies him in denying any rights to common mortals — the position aspired to by Raskolnikov in Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, for example. In Odd John, John himself, apprehended at 10 by a policeman while committing burglary, stabs the policeman to the heart to avoid coming to official attention. Later he and other superhumans kill the crew of a boat they started out to rescue, for the same reason, and still later they induce the population of a remote Pacific island to commit mass suicide so that they can establish a colony there. The narrator is troubled by these actions, but tells himself that these are beings of superior moral insight, and if they think they are justified, they must be right and he must be wrong.

Odd John (Methuen, 1935). Cover by Eric Fraser

This may be the hardest part of the novel to deal with. On one hand, it looks like a justification of murder and even genocide by a fantasy of superiority, along Raskolnikovian lines; and the narrator’s reluctant acceptance of it seems like a mark of submission to that fantasy. It’s telling that the narrator accepts John’s nickname for him, “Fido,” and never tells us his legal name. On the other hand, that reading itself could be taken as a rejection of the novel’s premise, which is that its characters genuinely are superhuman, not only intellectually but in moral insight; if we accepted that premise, and took it seriously, perhaps it would lead us to exactly the conclusion that Fido struggles to accept.

I’m also struck by a nuance of the narrative: At one point, Fido makes unmistakable hints of a sexual relationship between John and his mother, while refusing to describe it explicitly, saying he doesn’t want to destroy his respectable reputation. But he has no hesitation in describing John’s various homicides, which he knew about but didn’t report to any legal authorities; apparently he doesn’t fear that this will get him in legal trouble or even damage his reputation. Perhaps killing indigenous people on a remote island might be accepted — though Leopold’s policies in the Congo had long since been an international scandal — but killing a policeman to escape arrest, for example, doesn’t seem something that a reporter ought to condone or keep silent about.

|

|

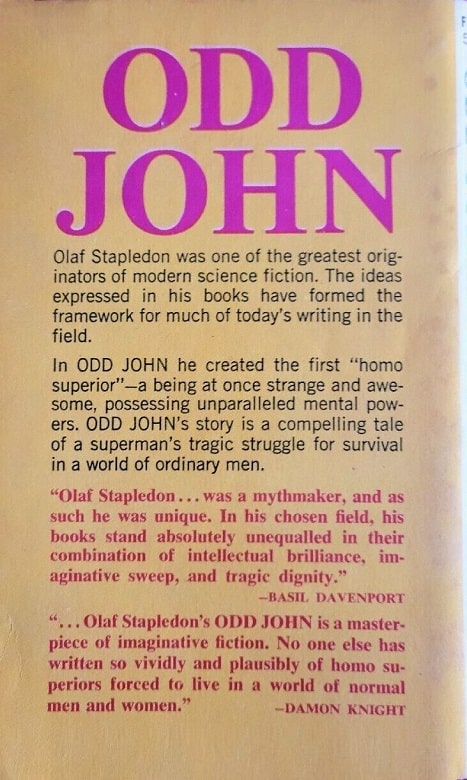

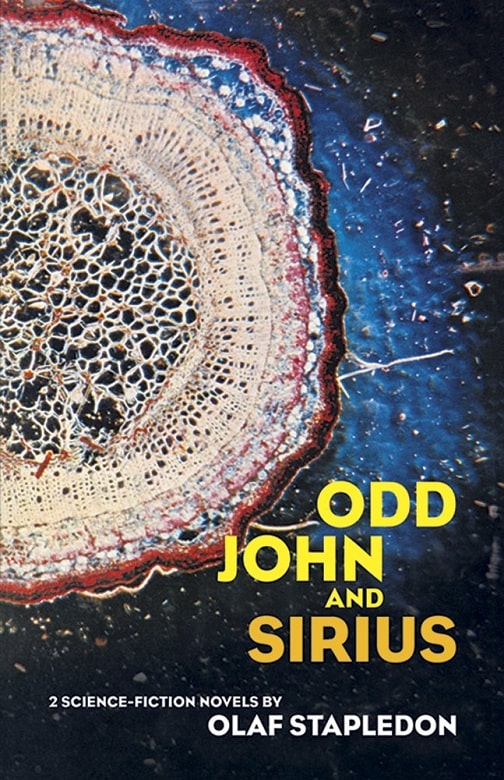

Odd John and Sirius (Dover Publications, 1972; cover by

Lewis R. Wolberg), and cover page of the 1936 Dutton hardcover

It’s noteworthy that John’s first companions are an African boy, portrayed as hyperactive and focused on the physical side of things, and an Asiatic girl, shown as emotionally unexpressive — stereotypes common in Stapledon’s time. Stapledon also seems to embrace popular views of Tibet as a center of mystical insight or psychic powers, when he suggests that all the superhumans derive from a single original mutation somewhere in Central Asia: what Richard Goldschmidt would describe in his 1940 defense of macromutationist theories of evolution as a “hopeful monster.”

Many generations of science fiction fans have found this idea of superhumanity tempting; I certainly did when I first read Odd John. It has a natural appeal to bright adolescents who have started to think abstractly, especially if people around them are unsympathetic to their questions and speculations. But if we remember that we’re among the lesser human beings that Homo superior would regard as animals, to be domesticated or exterminated, it doesn’t seem so benign. And maybe it’s one of Stapledon’s merits that he makes that disturbing corollary of his hypothesis explicit.

William H. Stoddard is a professional copy editor specializing in scholarly and scientific publications. As a secondary career, he has written more than two dozen books for Steve Jackson Games, starting in 2000 with GURPS Steampunk. He lives in Lawrence, Kansas with his wife, their cat (a ginger tabby), and a hundred shelf feet of books, including large amounts of science fiction, fantasy, and graphic novels. His last review for us was West of the Sun by Edgar Pangborn.

Interesting insights into a novel many SF fans have heard of but few have read (I haven’t read it despite owning a copy for years). “Gladiator” by Philip Wylie deals with similar ideas regarding Homo superior but from sometimes different perspectives. I’m glad you mentioned Marvel’s X-Men, I’m sure that Stan Lee would have had no hesitation in “borrowing” the term Homo superior for his merry mutants.

Julian May refers to Odd John’s plight – and subsequent dilemma – in detail, in her ‘Intervention/ Galactic Milieu’ trilogy/saga. (I never realized at the time it was a ‘real’ work of fiction). Nice piece – I’d consider reading it if I didn’t know how it was all going to end.

I don’t know about you, but I regularly reread favorite books, where necessarily I already know the ending; it’s how the author gets there that’s the source of pleasure when I do so. If you do the same then reading a book new to you, whose ending you’ve learned of, might also give you pleasure.

The way John’s behaviors are recounted above make him sound sociopathic, rather than “advanced”.

I’ve read it a number of times. It kind of supports Fandoms “Fans Are Slans” thing (yes we are, even without tendrils….) but I do question the whole “I’m superior, therefore, my morality is incomprehensible to you, and yours is inconsequential” aspects. Which makes it a good thing that John wants to remove himself from mundane society. So do the Slans. So does the hybrid intelligence in Sturgeon’s Baby is Three.

Wonderfully insightful review. I’m not sure why the policeman’s murder and the Oedipus engagement didn’t stand out in such contrast to me as they did here perhaps I’m too ‘close’ to it after reading this and nearly all his fiction for years?

But in line with your final comments, the malignant tone of a superman story should be, frankly, dealt with head on, which is partly why Odd John is such an odd story. Most don’t touch it.

How could it be otherwise though? Any sufficiently deep conversation on vegetarianism, or dolphin and ape captivity, would lead to an uncomfortable conversation on the value of different species’ lives. Wait, forget that, what about human trafficking and slavery?

I guess my point is that Stapledon took a chance to actually treat the issue with some of the respect it deserves in my view. His compassionate treatment of it through Fido’s eyes might be insecurity or honesty, maybe both.

And so the absurd contrast between Fido’s cavalier treatment of murder, and his awkward alluding to the taboo of mother/son sex for fear of repercussions is uncomfortable to be sure. Insecurity over sex overrides murder, but that seems to be a product of his culture. In the US today we glorify murder in every summer blockbuster. Incest between parents and kids is ‘properly’ relegated to underground comedians, right?

So I’m not defending it, but it doesn’t ruin Odd John for me (and the other immoral acts, given that perhaps our stories are scared of speculating that we could be seen as dogs.)

Finally, to round this contrast out some more, he did have a bit of a gluttonous attention towards highlighting the errors of WASP culture towards sex in his works. The 18th man (found throughout) projected a world to help the reader demystify sex in Last Men in London (chapter Paul and Sex). In Last and First Men, the 18th species has *96* sub sexes. And doesn’t Odd John himself succeed in having a male to male encounter as a teenager? And let’s not forget that in Sirius readers were given the scent of an animal to human affair).

I think taboo sexual interactions were a limited, but important part of his palette as an author. And while he served as a medic in WWI and saw death firsthand, the suppression of sexual activity may have been something that stood out as something to influence.

I’m not totally sure. And I’m not even confident I made a concrete point here 🙂 But I’m thankful for your article and a bit happy to have had a chance to soapbox a bit. Thanks