A (Black) Gat in the Hand Turns 100!: Erle Stanley Gardner’s ‘Getting Away With Murder’

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

(Gat — Prohibition Era term for a gun. Shortened version of Gatling Gun)

And A (Black) Gat in the Hand turns 100 today. With help from some friends, this column has managed to offer a hundred essays on the fascinating world of Pulp. April 8, 1949 was the day the Pulps died (I think that American Pie is one of the greatest songs of all time – couldn’t pass up the reference – with a tip of the fedora to William Lampkin for the phrase). On that day, Street & Smith announced they were quitting the Pulps. My favorite, Dime Detective, straggled on into 1952. But the days of the Pulps were effectively over.

But the love of Pulps lived on. Back in May of 2018, I kicked off my weekly Black Gate column as follows:

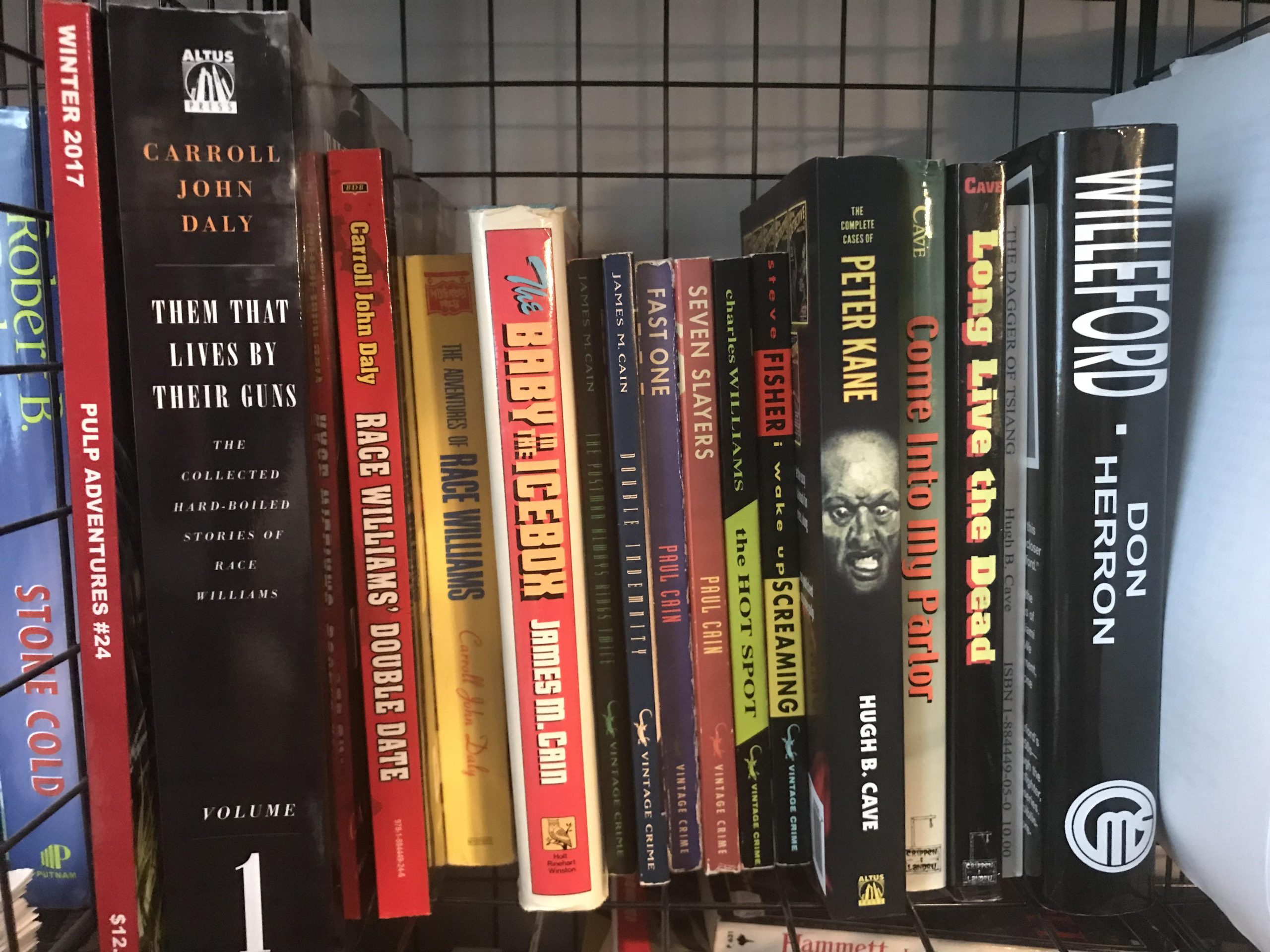

“Working from Otto Penzler’s massive The Black Lizard Big Book of Pulps, we’re going to be exploring some pulp era writers and stories from the twenties through the forties. There will also be many references to its companion book, The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories. I really received my education in the hardboiled genre from the Black Lizard/Vintage line. I discovered Chester Himes, Steve Fisher, Paul Cain, Thompson and more.

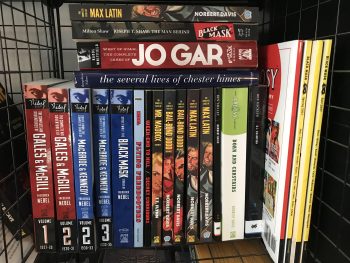

With first, the advent of small press imprints, then the explosion of digital publishing, Pulp-era fiction has undergone a renaissance. Authors from Frederick Nebel to Raoul Whitfield; from Carroll John Daly to Paul Cain (that’s 27 letters – we went all the way back around the alphabet – get it?) are accessible again. Out of print and difficult-to-find stories and novels have made their way back to avid readers.”

And thirty-one weeks later on December 31, (with help from friends, as I mentioned), I said this near the end of the final post in the series:

And thirty-one weeks later on December 31, (with help from friends, as I mentioned), I said this near the end of the final post in the series:

“It’s possible I could bring the column back for a limited run in the future, though I’d have to immerse myself in a pulp/hardboiled mood again.”

Turns out that ‘immersion’ was pretty much a given.

My area of expertise (presuming I even have one) is hardboiled PI stuff, which is mostly what I’ve written about. But A (Black) Gat has roamed all over the place – Westerns, Weird Menace, Hero Pulps, Horror, Science Fiction, Adventure, Spicy; and Movies, Radio, Television – the Pulps appeals to fans of all stripes. I continually work in more Robert E. Howard, because I think he’s the greatest Pulpster of them all. Friends who know a lot more than I do, are still contributing essays that I’m learning cool stuff from. Thanks to all those who have helped out- their names are prominent in the link to their essays, at the end of this post. Go check out their stuff!

What started out as a one-off hardboiled PI series at a World Fantasy Award-winning website, is going stronger than ever in this, it’s sixth summer. I’ve got a half-dozen different essays in the works right now, including essays on Jim Thompson, Cool and Lam (a favorite subject), Marvel Conan comic adaptations of non-Conan stories by REH, Roger Torrey, Frederick Nebel, and issues of Black Mask, and Speed Detective. But for number 100, I found something I found pretty cool.

Erle Stanley Gardner was one of the best-selling authors in the world during his time (that Agatha Christie lady was tough to beat). His tough attorney, Perry Mason – personified by Raymond Burr for a generation of readers – just as Basil Rathbone (Sherlock Holmes) and Arnold Schwarzenegger (Conan) are – is still well-known today. I like Mason well enough, but I’m a HUGE fan of his mismatched private eyes, Cool and Lam.

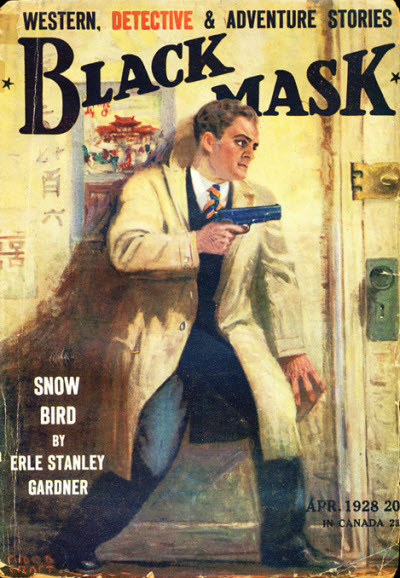

Before finding success in novels, he was a prodigious Pulpster and one of Black Mask’s most frequent contributors. And Lester Leith was a Detective Fiction Weekly Staple for over a decade.

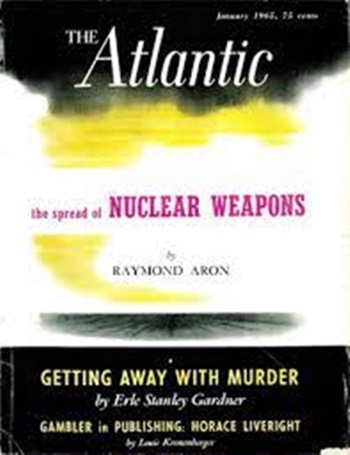

In the January 1965 issue of The Atlantic magazine, Gardner ruminated long and interestingly on his Pulp days. If you’re a Mason fan and haven’t run across this yet, settle in – you’re in for a treat.

Getting Away With Murder

An old pro in the writing of murder MYSTERIES, ERLE STANLEY GARDNER is the creator of one of the most widely read fictional characters in the English language. Perry Mason. Mr. Gardner broke into print as a contemporary of Dashiell Hammett and Carroll John Daly and at our urginghe has written this amusing account of their early days.

by Erle Stanley Gardner(The Atlantic – January 1965)

How, much does contemporary fiction reflect the mores of the times, and how much do the mores reflect contemporary fiction? Do books really cause the younger generation to feel that they must disrobe and hop into bed? These are questions similar to the one about the chicken and the egg.

How, much does contemporary fiction reflect the mores of the times, and how much do the mores reflect contemporary fiction? Do books really cause the younger generation to feel that they must disrobe and hop into bed? These are questions similar to the one about the chicken and the egg.

There is a growing tendency among contemporary writers to describe SEX in capital letters, and to describe violence in great detail, with minute accounts of bare fists spattering blood, teeth being kicked in, ribs cracking, and so forth. We know that young thugs are using utterly senseless and sadistic violence in their holdups, as some of them have admitted, “just for kicks.’’ Why? Who are they emulating? To what extent is their conduct influenced by contemporary fiction? The hardboiled school of realism likes to claim that it is writing of things as they are, but I believe that much of its work is the result of the sheer imagination of frustrated individuals.

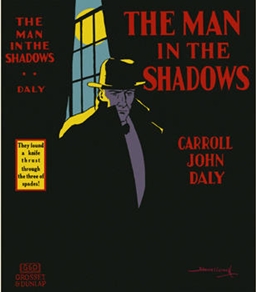

Life was seemingly more innocent and certainly more secure in the early days when Carroll John Daly, Dashiell Hammett, and I began writing for Black Mask, edited first by a man named Sutton and then by the susceptible Captain Joseph T. Shaw. Carroll John Daly helped to originate the hard-boiled school of detective writers when, some forty-odd years ago, he created the character of Race Williams.

Race Williams could well have been the parent of Mike Hammer. In fact, there are such startling resemblances that one can certainly suspect a family relationship. The big difference between Daly’s stories and the adventures of Mike Hammer is that Race Williams was too busy for sex. Race Williams would draw his gun and would ask the reader, “Was I bluffing?” The other man in the story evidently thought he was, because he would keep coming.

But Race Williams never hesitated. Daly would tell of how he tightened the trigger, how the round hole appeared in the man’s forehead, and of the look of surprise on the man’s face before the eyes started to glaze. Then the hole, which had been purple around the edges, would turn red and the man would pitch forward.

As I remember, the last line of one particular story read: “I sent him crashing the gates of hell with my bullet in his brain.”

Now, Carroll John Daly had never had the slightest experience with actual crime or criminals, much less with bullet wounds, except the one night he spent in the Tombs when an ingenious confidence man, wanting to give an address which would bear checking, simply took the telephone book of White Plains, New York, and selected a name, address, and telephone number at random. The name happened to be that of Daly.

When the police officers rapped at the door, Daly answered. They asked him if his name was Carroll John Daly. He said it was. That was enough. The next thing Daly knew he was on his way to jail.

I have always felt that Daly, who was tough in spirit but slender in physical build, used Race Williams as a means of satisfying subconscious impulses which he knew could never be gratified in real life.

Daly himself wanted no part of the rough and tumble. When winter came, he shut himself up in a house which was regulated by thermostatic control, so the temperature never varied over two degrees one way or the other.

He once told me, “You think I don’t get enough exercise and that I’m not an outdoor man. I want you to know that on some sunshiny days I think nothing of going out and walking the full width of this lot on the sidewalk — and this is a fifty-foot lot!”

Daly had a copyist who helped him in his work and who lived in New York. He never met the copyist. He never wanted to. Only on rare occasions could he be tempted to go to New York. It was a major undertaking for him. He lived in one of a row of identical houses. If he went more than a block away, he would sometimes have trouble picking out his own house when he came back since he so rarely saw it from the outside. Returning after dark from one of his infrequent trips to New York, he studied the row of houses, picked what he thought was the right one, and rang the bell.

A strange woman came to the door.

A strange woman came to the door.

Daly lifted his hat. “Can you tell me where Carroll John Daly lives?” he asked.

Why yes, he —why <>you’re Carroll John Daly!”

Daly bowed, “I know who I am, Madam; I am only trying to find out where I live.”

It was Daly’s habit to sleep until noon. He would then get up and spend the afternoon in carefree ease with the family or with any visitors who dropped in. After the family had been safely tucked in bed and the visitors had gone home, Daly would come to life. He would sit at his typewriter and pound out words until five or six o’clock in the morning. During those early hours the incomparably hard-boiled, bone-crunching, fastshooting Race Williams came to life.

DASHIELL HAMMETT, on the other hand, was one of the few writers I have known who had all the earmarks of genius and the temperament which goes with it. For a brief period he was a Pinkerton detective, and because of this experience, he dazzled credulous editors with a presumably encyclopedic knowledge of the underworld.

Dashiell was also a fast hand with a dictionary of criminalese and had a vast knowledge of editorial psychology. Heaven knows how these dictionaries of the underworld are Composed. Undoubtedly they represent considerable research, but how much of this research is done on the ground and how much in a library?

When Hammett started writing, there was a dictionary of the underworld which used the word “shamus” as a tag for a private detective. Hammett picked that word up, and it ran through all his stories. Every time one of his detectives would enter on the scene, someone would sneeringly refer to him as shamus. Since Hammett’s time, a whole school of realistic writers have had their characters refer to the private detective as a shamus.

Just where did that word come from? I have made it a point to try and find out, and I am completely baffled. The late Raymond Schindler, one of the world-famous private detectives, told me he had never heard the word. At my request, he had asked private detectives whom he employed, and they had never heard it used. I asked the wardens of various penitentiaries, and they told me they had never encountered the word except in fiction. During the past eighteen years, I have had quite a few contacts with the inmates of penitentiaries;

I have asked them about “shamus” and whether they had ever heard it applied to a private detective. Not one of them ever had.

Then one day I happened to be discussing the matter with a man who had worked for a Jewish haberdasher, and he told me he had heard the word used; it applied not to a private detective but to some sort of phony. No matter; thanks to Dashiell, the Dictionary of American Underworld Lingo lists “shamus” as a Jewish-American word meaning a policeman or a prison guard, and the American Thesaurus of Slang lists it as applying to a policeman, an informer, or a stool pigeon.

It has been many years since Dashiell Hammett first put the word into circulation. Today the general reading public considers “shamus” a slang term customarily used by the underworld in describing the private detective. It assumes that the writer who uses it knows his way around.

At first, Editor Shaw and Dashiell didn’t hit it off. Hammett became enraged over a rejection by Shaw and quit writing for Black Mask. I was in New York at the time, and after conferring with Shaw, wrote Hammett a letter pleading with him to return to the fold.

Later on, of course, after the fame of The Maltese Falcon, Hammett could do no wrong. Captain Shaw not only went all out for Hammett but tried to get writers to follow the Hammett style. One of my big differences with Shaw came when I accused him of trying to “Hammettize” the magazine.

However, before Hammett and Shaw had become such buddies, Hammett wrote a story which contained an expression that gave Shaw quite a jolt. He deleted it from the manuscript and wrote Hammett a chiding letter to the effect that Black Mask would never publish vulgarities of any sort.

Hammett promptly wrote a story in which he laid a deliberate trap for Joe Shaw.

One of the characters in the story, meeting another one, asked him what he was doing these days, and the other shamefacedly admitted that he was “on the gooseberry lay.”

Had the editor known it, this meant simply that the character was making his living by stealing clothes from clothellines, preferably on a Monday morning. The expression goes back to the old days of the tramp who from time to time needed a few pennies to buy food. He would wait until the housewife had put out her wash; then he would descend on the clothesline, pick up an armful of clothes, and scurry away to sell them.

In the same story, and as part of the same trap, Hammett had another character ask what he was doing, and the chap said very proudly that he was now a “gunsel” for such and such an underworld character.

In the same story, and as part of the same trap, Hammett had another character ask what he was doing, and the chap said very proudly that he was now a “gunsel” for such and such an underworld character.

Shaw had the reaction which Hammett had expected. He wrote Hammett telling him that he was deleting the “gooseberry lay” from the story, that Black Mask would never publish anything like that. But he left the word “gunsel” because Hammett had used it so casually that Shaw took it for granted that the word pertained to a hired gunman. Actually, “gunsel,” or “gonzel,” is a very naughty word with no relation whatever to a bodyguard, a gunman, or a torpedo.

What happened?

All the writers of the hard-boiled school of realism started talking about a gunsel as the equivalent of a gunman. The usage has persisted. Recently, a magazine of national circulation, featuring the death of a gunman, described it on the cover as “The Short, Bitter Life of a Gunsel.”

A few years ago, I read a book purportedly written by a man who enjoyed a firsthand contact with the underworld, a story of stark realism. The author continually referred to the gunmen as “gunsels.”

It has been at least thirty-five years since Dashiell Hammett played his little joke on Captain Joseph T. Shaw, but the aftereffects of that joke are still seen in American murder stories.

Then there was the time Hammett went into the office of a magazine which had long been after him for a novelette. Hammett had a hastily written novelette in his overcoat pocket. He submitted it to the editor, who was overjoyed and waited a discreet interval for Hammett to leave.

Finally, Hammett said, “Well, aren’t you going to read it?”

Why, yes,” the editor said. “I’ll get at it right away.”

All right,” Hammett said. “I’ll wait. If you don’t like it, I can take it somewhere else.”

So the editor read it and said he liked it.

All right, then, give me a check,” Hammett said. “I believe you do pay on acceptance, don’t you?”

The editor explained that his way of doing business was to send out vouchers through the accounting department.

Hammett reached for the manuscript. The harassed editor called the accounting department and ordered a check for Hammett forthwith.

Hammett pocketed the check.

There are two or three expressions that will have to be deleted from the manuscript,” the editor said. “ They are a little broad for this magazine, but we’ll touch it up.”

Hammett drew himself up with dignity. “No one touches a Hammett manuscript except Dashiell Hammett!” he exclaimed, and with a regal gesture swept the manuscript into his pocket. “I’ll delete those expressions,” he said, and stalked out of the office, the check in one pocket, the manuscript in the other.

The editor sat in open-mouthed confusion.

The inevitable happened. Hammett cashed the check, and cash and Hammett meant but one thing. It was a combination which needed one more ingredient and plenty of ice.

The editor scheduled the manuscript for publication and featured it on the pictorial cover, which was printed in Chicago some time before the printing of the magazine. Then he engaged in a frantic search trying to find Hammett.

Hammett was in no condition to be found. Various people located him and tried to get him going, but as soon as he got going he went in the wrong direction.

Meantime the harassed editor was stuck with the printed covers. He finally had a slip printed explaining that because of illness on the part of Dashiell Hammett the story would appear in a subsequent issue. He hired girls by the hundred to paste these slips on the covers of the magazines. By then it was too late to get new covers.

Happily, one afternoon Hammett attained a measure of sobriety while riding in a taxicab. He pushed his hand down into his overcoat pocket, found the crumpled manuscript, remembered that he had agreed to delete certain expressions, pulled a pencil out of his pocket, scrawled corrections on the manuscript, stopped off at a speakeasy, and paid the cabdriver to take the manuscript to the editorial office.

The relieved editor rushed the story into the magazine and hired more girls to pull the printed slips off the covers that had already been “treated.” It was a great day for the New York unemployed.

It is an interesting commentary on the subconscious that men like to identify themselves vicariously with characters who are devastatingly successful in the field of romance; and women, apparently, are not averse to reading stories of feminine surrender to dominant persons who are ruthlessly masculine. But the minute the relationship becomes sanctioned by convention it tends to lose its literary charm. I learned this the hard way. Years ago I had created a highly successful character who ran for years in the wood pulp magazines. He was known as Ed Jenkins, the “Phantom Crook.”

It is an interesting commentary on the subconscious that men like to identify themselves vicariously with characters who are devastatingly successful in the field of romance; and women, apparently, are not averse to reading stories of feminine surrender to dominant persons who are ruthlessly masculine. But the minute the relationship becomes sanctioned by convention it tends to lose its literary charm. I learned this the hard way. Years ago I had created a highly successful character who ran for years in the wood pulp magazines. He was known as Ed Jenkins, the “Phantom Crook.”

Jenkins was wanted by the police and hated by the underworld. The police blamed him for crimes they couldn’t solve. The underworld egged the police on with phony tips from unscrupulous stool pigeons. Ed Jenkins simply didn’t care. He lived a life in the shadows, outwitting both the police and the underworld. He depended solely on quick thinking and diabolical ingenuity. As he frequently expressed it, “ kite police can arrest you for having a gun on you, but they can’t arrest you for having your wits about you.”

Then the rich, socially prominent Helen Chadwick fell in love with Ed Jenkins. She wanted to have her father use his political influence to get a governor’s pardon so that Jenkins could start anew.

Jenkins would apparently toy with this idea while being exposed to Helen’s charms, but knowing that he could only bring misfortune to the girl he loved, he would excuse himself for a moment, leave the room, then slip unobtrusively out of some convenient window and vanish once more into the night, wanted by the police, pursued by the underworld.

By the time the next story started, Helen would be making frantic efforts to find him again, would eventually be successful, and would plead with him to let her rehabilitate his good name.

Jenkins would waver, but knowing that in the long run there was no simple solution, knowing that if he married Helen her life would be one of constant danger, he would get her into a position of temporary safety, and then, using ingenuity to outwit crooks and police alike, he would again slip through the fingers of the underworld into the dark alleys he knew so well, detour past the police, and vanish into the depths of San Francisco’s Chinatown, where an old Chinese philosopher always gave him shelter.

Eventually, the clamoring pressures of the reading public became too great. Letters of protest came pouring in. I let Ed Jenkins and Helen Chadwick get married.

I started the next story after their marriage, with a scene in which I tried to show some measure of domestic bliss. Ed Jenkins was in a hotel room looking out the window, making a surreptitious survey of the street below, while his bride, the erstwhile Helen Chadwick, was busily ironing her dress.

Captain Joseph T. Shaw, editor of Black Mask, sent the story back with a gasp of horror. The idea of having Helen Chadwick without a dress in a hotel room with Ed Jenkins Black Mask would never stand for such a risque situation as that.

So I got mad and killed Helen off.

It was a horrible thing to do. My daughter wouldn’t speak to me for a month. Readers wrote in quivering with indignation.

Captain Shaw accepted her death with equanimity. He probably felt it served the girl right for removing her dress in the presence of her husband.

Dashiell Hammett achieved fame with The Maltese Falcon, and shortly after that in The Thin Man he discovered that marriage had its lighter moments. His detective in The Thin Man plunged into bed to enter into a relationship which was legally and morally sanctioned.

Dashiell Hammett achieved fame with The Maltese Falcon, and shortly after that in The Thin Man he discovered that marriage had its lighter moments. His detective in The Thin Man plunged into bed to enter into a relationship which was legally and morally sanctioned.

Editors woke up to the fact that they had been missing something, and some prelate even preached a sermon based on Hammett’s story, pointing out that marriage could be fun.

It was too late to do me any good. I couldn’t bring Helen Chadwick back to life.

It is perhaps a commentary on the trend of modern times that the late Ian Fleming, surveying the situation, felt that the solution offered by Dashiell Hammett some thirty-odd years earlier would no longer appeal to the readers.

In any event, he had his hero lead with his chin in such a way that his bride of a few hours became defunct. In view of the standards of super intelligence usually employed by James Bond, the manner in which he betrayed his wife into a fatal trap is almost indicative of the fact that subconsciously he wanted to get rid of her as fast as Ian Fleming did.

A burnt child dreads the fire.

For some thirty-two years now, Perry Mason and Della Street have been working side by side, each apparently potential matrimonial material, but each far too occupied with the intricacies of the case on which they are working to realize the biological possibilities of the association.

Indignant readers write in and want to know when the pair are going to get married.

As an author I am in love with Della Street. I am not going to kill her off. And when better authors than I am find themselves unable to cope with the problem of a married hero, I’m not going to paint myself into that corner again.

Other ESG essays at Black Gate

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: A Q&A with Charles Ardai

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Cool & Lam are Back

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Cool & Lam’s ‘The Count of Nine’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Cool & Lam’s ‘Top of the Heap’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Erle Stanley Gardner’s “The Shrieking Skeleton”

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Erle Stanley Gardner: Ed Jenkins, The Phantom Crook

Erle Stanley Gardner on Mysteries

Prior Posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2023 Series (9)

Back Down those Mean Streets in 2023

Back Down those Mean Streets in 2023

Will Murray on Hammett Didn’t Write “The Diamond Wager”

Dashiell Hammett – ZigZags of Treachery

Ten Pulp Things I Think I Think

Evan Lewis on Cleve Adams

T,T, Flynn’s Mike & Trixie (The ‘Lost Intro’)

John Bullard on REH’s Rough and Ready Clowns of the West – Part I (Breckenridge Elkins)

John Bullard on REH’s Rough and Ready Clowns of the West – Part II

William Patrick Murray on Supernatural Westerns, and Crossing Genres

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2022 Series (16)

Asimov – Sci Fi Meets the Police Procedural

The Adventures of Christopher London

Weird Menace from Robert E. Howard

Spicy Adventures from Robert E. Howard

Thrilling Adventures from Robert E. Howard

Norbert Davis’ “The Gin Monkey”

Tracer Bullet

Shovel’s Painful Predicament

Back Porch Pulp #1

Wally Conger on ‘The Hollywood Troubleshooter Saga’

Arsenic and Old Lace

David Dodge

Glen Cook’s Garrett, PI

John Leslie’s Key West Private Eye

Back Porch Pulp #2

Norbert Davis’ Max Latin

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2021 Series (7 )

The Forgotten Black Masker – Norbert Davis

Appaloosa

A (Black) Gat in the Hand is Back!

Black Mask – March, 1932

Three Gun Terry Mack & Carroll John Daly

Bounty Hunters & Bail Bondsmen

Norbert Davis in Black Mask – Volume 1

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2020 Series (21)

Hardboiled May on TCM

Hardboiled May on TCM

Some Hardboiled streaming options

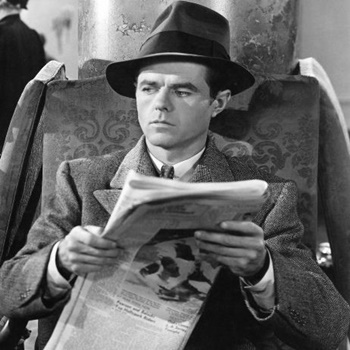

Johnny O’Clock (Dick Powell)

Hardboiled June on TCM

Bullets or Ballots (Humphrey Bogart)

Phililp Marlowe – Private Eye (Powers Boothe)

Cool and Lam

All Through the Night (Bogart)

Dick Powell as Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar

Hardboiled July on TCM

YTJD – The Emily Braddock Matter (John Lund)

Richard Diamond – The Betty Moran Case (Dick Powell)

Bold Venture (Bogart & Bacall)

Hardboiled August on TCM

Norbert Davis – ‘Have one on the House’

with Steven H Silver: C.M. Kornbluth’s Pulp

Norbert Davis – ‘Don’t You Cry for Me’

Talking About Philip Marlowe

Steven H Silver Asks you to Name This Movie

Cajun Hardboiled – Dave Robicheaux

More Cool & Lam from Hard Case Crime

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2019 Series (15)

Back Deck Pulp Returns

A (Black) Gat in the Hand Returns

Will Murray on Doc Savage

Hugh B. Cave’s Peter Kane

Paul Bishop on Lance Spearman

A Man Called Spade

Hard Boiled Holmes

Duane Spurlock on T.T. Flynn

Andrew Salmon on Montreal Noir

Frank Schildiner on The Bad Guys of Pulp

Steve Scott on John D. MacDonald’s ‘Park Falkner’

William Patrick Murray on The Spider

John D. MacDonald & Mickey Spillane

Norbert Davis goes West(ern)

Bill Crider on The Brass Cupcake

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2018 Series (31)

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2018 Series (31)

George Harmon Coxe

Raoul Whitfield

Some Hard Boiled Anthologies

Frederick Nebel’s Donahue

Thomas Walsh

Black Mask – January, 1935

Norbert Davis’ Ben Shaley

D.L. Champion’s Rex Sackler

Dime Detective – August, 1939

Back Deck Pulp #1

W.T. Ballard’s Bill Lennox

Day Keene

Black Mask – October, 1933

Back Deck Pulp #2

Black Mask – Spring, 2017

Frank Schildiner’s ‘Max Allen Collins & The Hard Boiled Hero’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Campbell Gault

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: More Cool & Lam From Hard Case Crime

MORE Cool & Lam!!!!

Thomas Parker’s ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’

Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part One)

Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part Two)

William Patrick Maynard’s ‘The Yellow Peril’

Andrew P Salmon’s ‘Frederick C. Davis’

Rory Gallagher’s ‘Continental Op’

Back Deck Pulp #3

Back Deck Pulp #4

Back Deck Pulp #5

Joe ‘Cap’ Shaw on Writing

Back Deck Pulp #6

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE DEFINITIVE guide to Conan. He also organized 2023’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, and XXXIII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

Congrats on hitting the century mark, Bob!

I need to read more Gardner. Over the past couple of years, Ive read three Perry Masons and I’ve enjoyed them a lot, even as I’ve noticed the ways they’re different from the show, which I love. (In two of the books, Perry didn’t set foot in a courtroom; maybe they were just outliers.) I have some of the Hard Case Cool and Lam books, but I haven’t read any of them.

Maybe this summer…

Thanks. Glad you hopped on board for the ride!

I only read my first Mason a couple years ago, and I’ve read about five so far. I like them. The earlier ones seem to be more typical hardboiled PI fare, while they became more ‘lawyerly.’ That transition seemed to happen around book 10 or 12, I think. Pick something from the middle or later for a more typical Mason.

I’m reviewing the most recent Hard Case crime reissue of Cool and Lam – ‘Fools Die on Friday.’ It’s one of my least favorites in the entire C&L series, but I still like it. Not the one I’d recommend first, though.

It’s almost impossible for me to make a Top Five PI series list, but I think Cool and Lam make the cut.

Congratulations on hitting 100 posts, Bob! You and your guests’ pulp blogs have given me great joy in discovering some pulp genres I never thought I’d be interested in. Here’s to several hundred more posts! (and emptying my bank account with having to buy more books!!!)

Thanks, John. Glad you joined in this year.

So much Pulp – so little money to buy it with. 🙂

I’m re-reading Howard’s Cormac Mac Art stories before I tackle the second book by Offutt (I read the first one a couple years ago and loved it). There’s a dearth of essays about Cormac on the web (possibly even none).

I might try something about him, too. I’d write just REH for six months or more, if I could. But so much to cover.