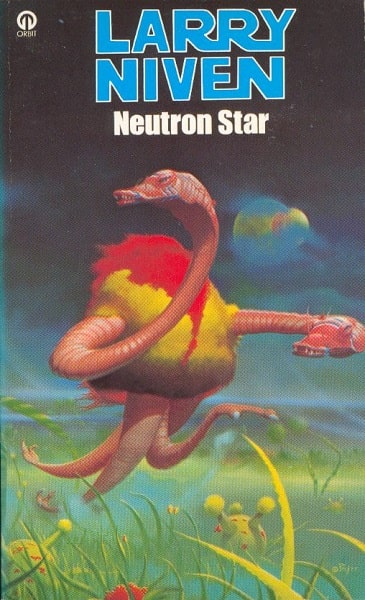

Vintage Treasures: Neutron Star by Larry Niven

|

|

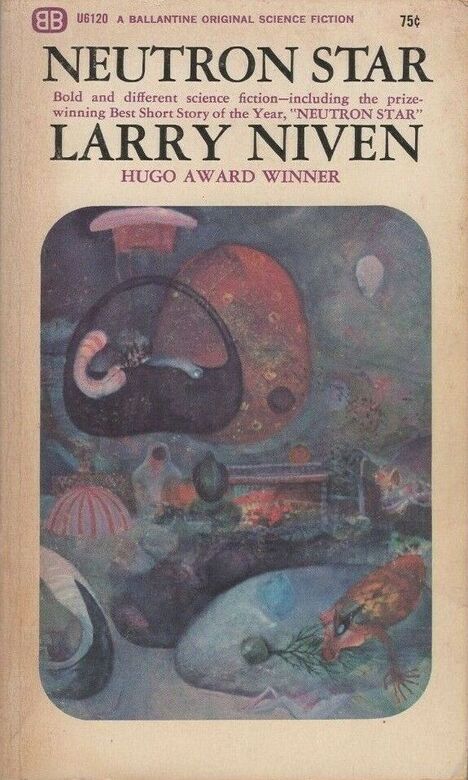

Neutron Star (Ballantine Bools, April 1968). Cover artist unknown

As I was preparing last week’s Vintage Treasures article (on Poul Anderson’s Fire Time), I realized that the next book on deck was Neutron Star, by Larry Niven, one of the most important science fiction collections of the 20th Century. And I simultaneously realized we’ve never done a Vintage Treasures feature on Niven before, a pretty serious oversight. (For comparison purposes, as I was assembling reference links at the bottom of my Fire Time piece, there simply wasn’t room to include the dozens of articles we’ve written on Anderson.) In fact, other than a pair of reviews by Fletcher Vredenburgh, two blog posts on Convergent Series by Steven Silver, and a note on the 1973 Skylark Award by Rich Horton, we’ve had virtually no coverage of Niven at all on Black Gate.

I’m to blame for this. Niven is, unquestionably, one of the most important science fiction writers alive today. But I was never a fan of his novels (I made two attempts to read his classic Ringworld, before giving up for good in the early 80s). His short stories, however, are a different matter, and I’m very glad to finally have the chance to discuss his first collection, the groundbreaking Neutron Star, first published as a paperback original by Ballantine Books in April 1968.

[Click the images to be drawn inexorably toward larger versions.]

|

|

Neutron Star (Ballantine Books reprint, July 1971). Cover by Michael McInnerney

Larry Niven has an interesting background. His great-grandfather was Edward L. Doheny, the famed oil tycoon who drilled the first successful well in Los Angeles in 1892, and who was eventually caught up in the Teapot Dome scandal in the 1920s. Niven has a degree in mathematics from Washburn University in Topeka, Kansas, and published his first science fiction story, “The Coldest Place,” in the December 1964 issue of If magazine.

It didn’t take long for Niven to take to science fiction writing as his true vocation. Within two years he was publishing steadily in If and Galaxy, and in fact Neutron Star consists entirely of short stories published during an extraordinary 14-month period between October 1966 and December 1967 (plus one original tale, “Grendel”).

Frederik Pohl picked Niven out of the slush pile at If, and it was that discovery — one of many, really — that helped cement his reputation as one of the finest editors in the field. Just as John W. Campbell had done with Astounding in the late 30s and 40s, building an extraordinary stable of writers who revolutionized the genre in its first Golden Age, so Pohl did in the 60s with If and Galaxy, nurturing and publishing an extraordinary array of top writers, including R. A. Lafferty, Jack Vance, Wilson Tucker, Keith Laumer, Fred Saberhagen, Harlan Ellison, John Brunner, Thomas M. Disch, James H. Schmitz, Fritz Leiber, Gordon R. Dickson, Gene Wolfe, Robert Moore Williams, Gardner Dozois, Piers Anthony, John Sladek, Robert Silverberg, Algis Budrys, Neal Barrett, Jr., Bob Shaw, Andrew J. Offutt, Roger Zelazny, Vernor Vinge, Terry Carr, A. Bertram Chandler, and countless others.

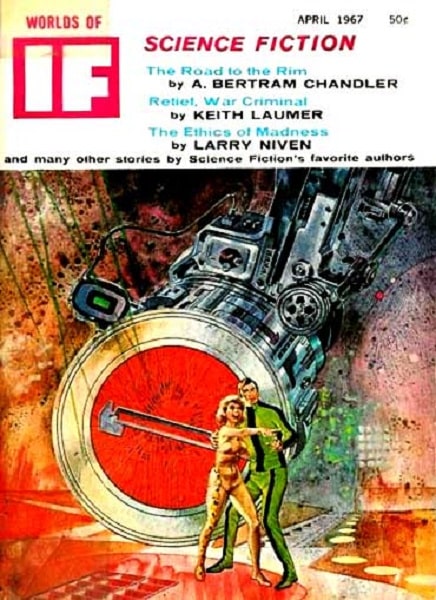

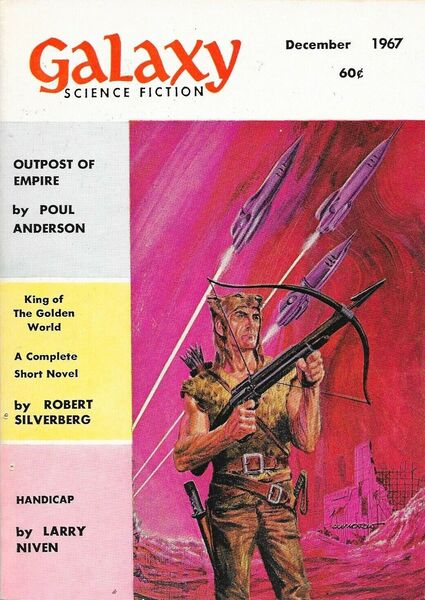

|

|

|

|

|

|

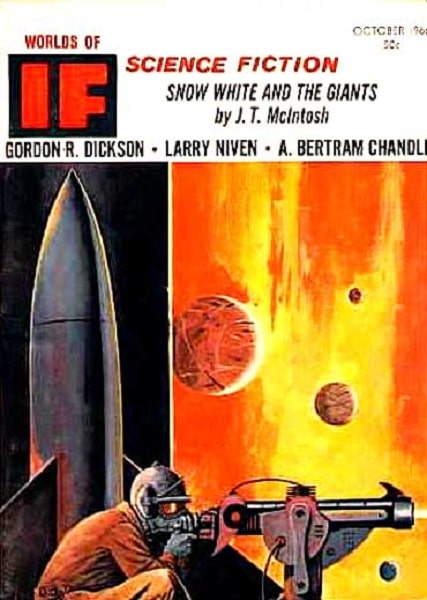

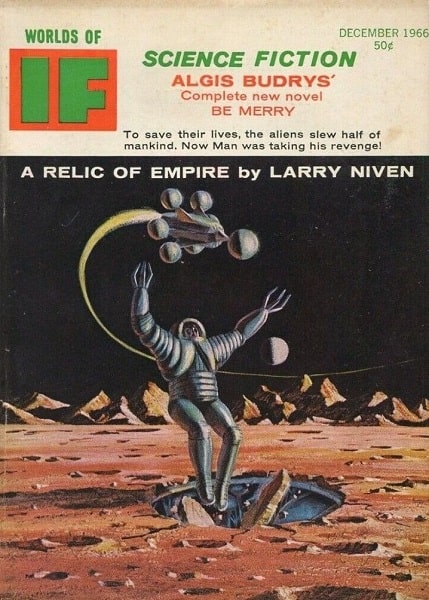

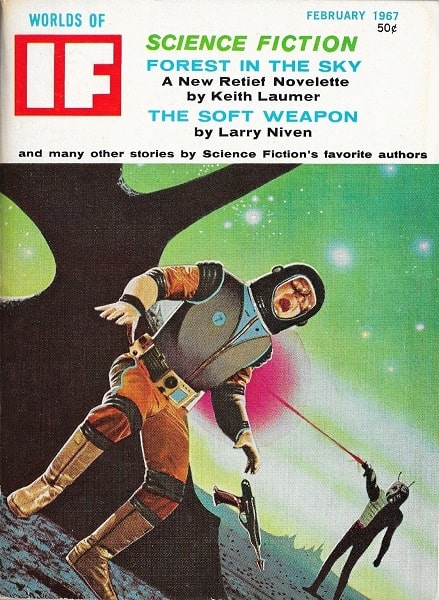

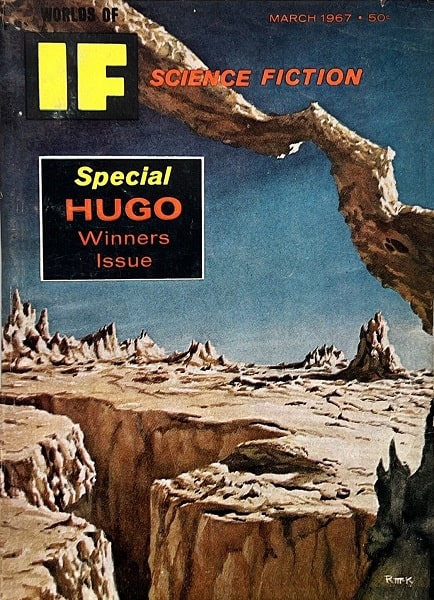

Original magazine appearances for the stories in Neutron Star, all edited by Frederik Pohl:

If magazine, October and December 1966, and February, March, and April 1967, and Galaxy,

December 1967. Covers: Adkins, Jack Gaughan, Wenzel, McKenna, Gray Morrow, Gray Morrow

Under Pohl’s editorship, If won the Hugo Award for Best Professional Magazine for three consecutive years: 1966, 1967 and 1968 — not coincidentally, the period when Niven was appearing regularly.

The stories collected in Neutron Star are all part of Niven’s Tales of Known Space, one of the most famous future history settings in the genre. It has been explored by numerous writers (as a shared universe that produced over a dozen anthologies and novels in the spin-off Man-Kzin Wars series), and spans around a thousand years.

On his own, Niven published half a dozen collections of tales set in Known Space:

Neutron Star (1968)

The Shape of Space (1969)

Tales of Known Space (1975)

The Long ARM of Gil Hamilton (1976)

Crashlander (1994)

Flatlander (1995)

Here’s an excerpt from the Wikipedia entry on Known Space.

Known Space is the fictional setting of about a dozen science fiction novels and several collections of short stories by American writer Larry Niven. It has also become a shared universe in the spin-off Man-Kzin Wars anthologies… The stories span approximately one thousand years of future history, from the first human explorations of the Solar System to the colonization of dozens of nearby systems. Late in the series, Known Space is an irregularly shaped “bubble” about 60 light-years across.

The epithet “Known Space” refers to a small region in the Milky Way galaxy, one centered on Earth. In the future that the series depicts, spanning roughly the third millennium, humans have explored this region and colonized many of its worlds. Contact has been made with other species, such as the two-headed Pierson’s Puppeteers and the aggressive felinoid Kzinti. Stories in the Known Space series include events and places outside of the region called “Known Space” such as the Ringworld, the Pierson’s Puppeteers’ Fleet of Worlds and the Pak homeworld.

The Tales were originally conceived as two separate series, the Belter stories set roughly from 2000 to 2350 CE and the Neutron Star / Ringworld stories set in 2651 CE and later. The earlier, Belter period features solar-system colonization and slower-than-light travel with fusion-powered and Bussard ramjet ships. The later, Neutron Star, period features faster-than-light ships using “hyperdrive”. Niven implicitly joined the two settings as a single fictional universe in the short story “A Relic of the Empire” (If, December 1966), by using background elements of the Slaver civilization from the Belter series as a plot element in the faster-than-light setting. In the late 1980s — having written almost no Tales of Known Space in more than a decade — Niven opened the 300-year gap in the Known Space timeline as a shared universe, and the stories of the Man-Kzin Wars volumes fill in that history, bridging the two settings.

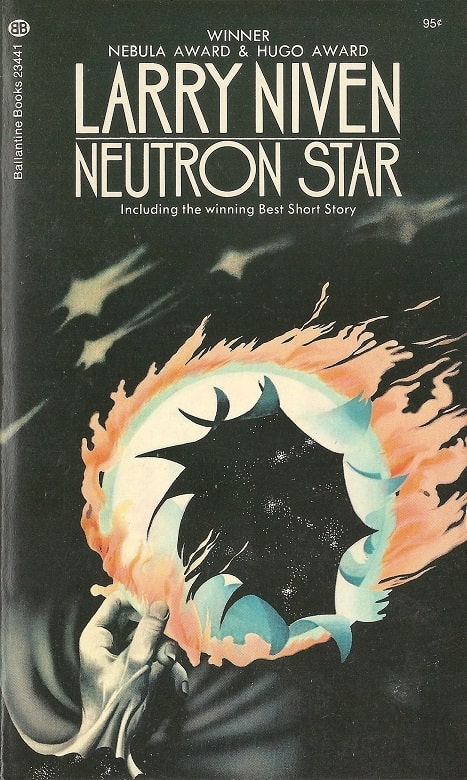

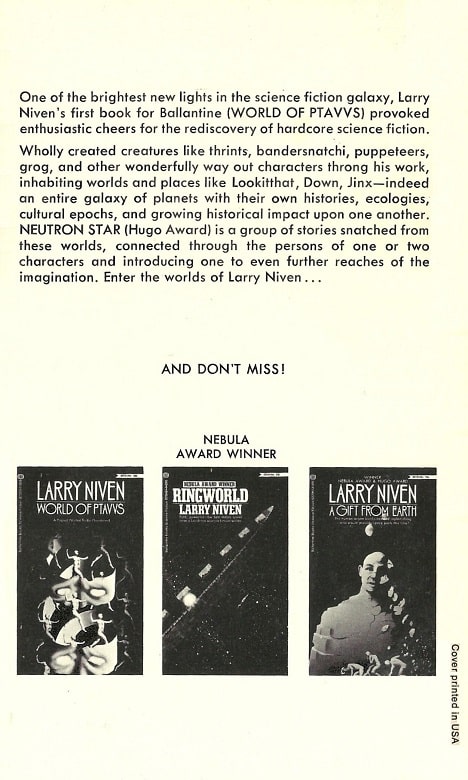

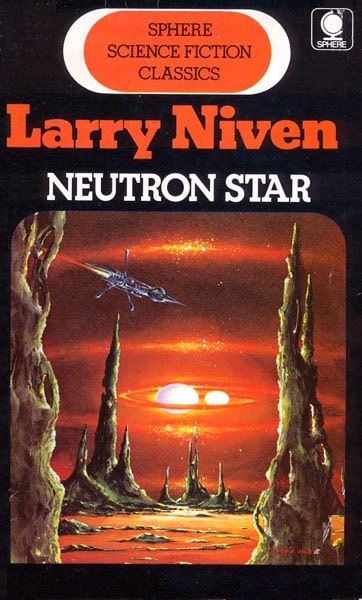

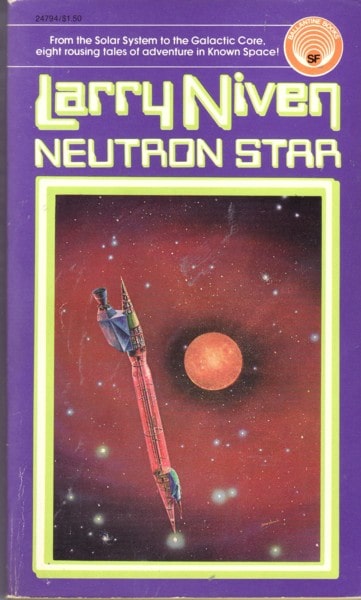

Neutron Star remained in print for decades, with multiple reissues over the years. Here’s a few of the more recognizable.

|

|

|

Neutron Star later editions: Sphere (1972), Ballantine (August, 1975),

Orbit (April, 1978). Covers by Eddie Jones, Rick Sternbach, and Peter Jones

The stories in Neutron Star were all published 1966 and 67, mostly in IF magazine, and all were edited by Fred Pohl. All the stories are all set in Known Space. The collection includes the novella “The Soft Weapon,” the Nebula nominee “Flatlander,” the Hugo Award winning title story, and one original tale, “Grendel.”

Here’s the complete Table of Contents.

“Neutron Star” (If, October 1966) — Hugo Award winner

“A Relic of the Empire” (If, December 1966)

“At the Core” (If, November 1966)

“The Soft Weapon” (If, February 1967)

“Flatlander” (If, March 1967) — Nebula nominee

“The Ethics of Madness” (If, April 1967)

“The Handicapped” (Galaxy, December 1967)

“Grendel” (original to this collection)

The Internet Science Fiction Database doesn’t usually include story-by-story summations, but for Neutron Star the editors made an exception. Here are the handy story summaries from ISFDB.

“Neutron Star”

— A human pilot is hired by an alien species to fly past a neutron star and investigate what mysterious force killed those who last attempted it.

“A Relic of the Empire”

— A xenobiologist captured on an isolated planet by a crew of space pirates uses his knowledge of the unique species he is studying to escape.

“At the Core”

— A human is hired by aliens to test pilot their new space vessel to the core of the galaxy and back.

“The Soft Weapon”

— Humans and aliens fight for control of an ancient alien weapon.

“Flatlander”

— A pair of humans travel to a planet described to them as the most unusual in the galaxy.

“The Ethics of Madness”

— In the future, the autodoc treatments which keep a man’s paranoia under control fail, and he commits a terrible crime, which result in his being hunted by the survivor who wants revenge.

“The Handicapped”

— None

“Grendel”

— A pair of human adventurers investigate the kidnapping of a distinguished alien from a space liner.

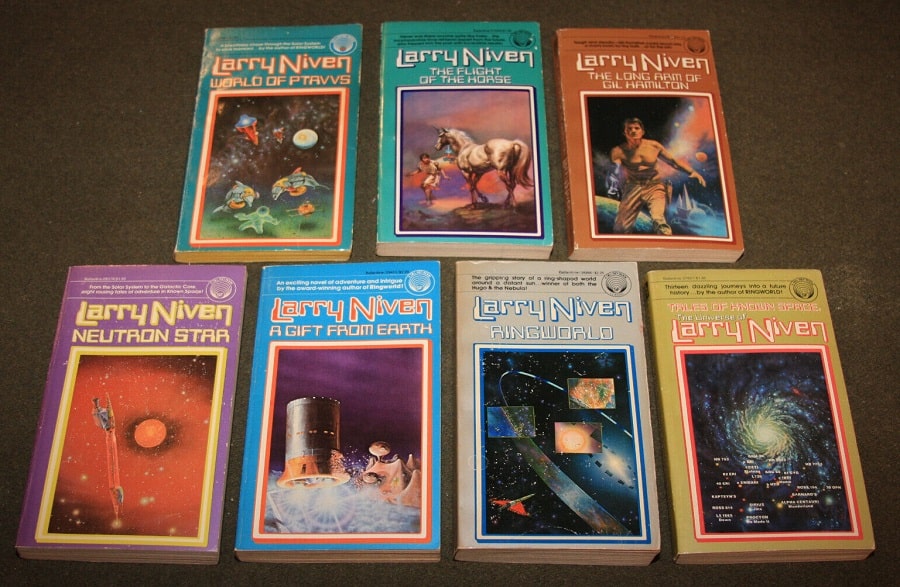

Ballantine/Del Rey was Larry Niven’s publisher for most of his career, keeping the bulk of his work in print in paperback for decades. His work was a fixture on store shelves in the same way as Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, Poul Anderson, J.R.R. Tolkien, and other mainstays of well-stocked science fiction bookstores. Here’s a look at some of his most popular titles in their 80s-era Ballantine editions.

The Ballantine/Del Rey Larry Niven

Neutron Star is still read, enjoyed, and widely discussed today. Here’s an excerpt from the enthusiastic review by Alan Brown, published last year at Tor.com. (I was pleased to see he shares my opinion on Fred Pohl’s impact on modern SF.)

I recently ran across Neutron Star… and as I read it, I realized how much I enjoyed those shorter works—especially those where the protagonist faces a scientific puzzle, and must solve it to survive…

Neutron Star was first published in 1968, and consists entirely of stories selected by editor Fredrick Pohl for Galaxy and If in the preceding two years, demonstrating that Niven is one of the many authors whose career benefitted from Pohl’s editorial judgement. And as I look back on science fiction in the mid-to-late 20th century, I am increasingly convinced that, while John Campbell tends to get more attention, Fredrick Pohl deserves significant credit for his lasting impact on SF publishing…

The tales in this collection are excellent examples of what makes a good short story. They are very well constructed, the narration is clear and simple, and each very cleverly unravels the scientific mystery at its center. The story “Neutron Star” starts the collection off with a bang. It is easily the best story in the book, and some rank it among the greatest science fiction short stories ever written — it’s no surprise it won the Hugo for Best Short Story in 1967. The tale follows the adventures of pilot Beowulf Shaeffer as he travels to explore the mysterious star BSV-1 on behalf of the mysterious and cowardly alien race called the Puppeteers. BSV-1 is, as you might guess from the title, a neutron star, a supergiant star that has collapsed down into an incredibly dense sphere, comprised almost entirely of neutrons.

Shaeffer is a former space liner pilot, having worked for the now-bankrupt Nakamura Line, whose profligate lifestyle has put him deeply in debt. The Puppeteers hire him to investigate the star, showing him a ship used by a previous expedition. It has a Puppeteer-manufactured General Products hull, made of a crystalline substance that supposedly will pass nothing but visible light. The insides of the ship are twisted and distorted, and nothing of the original crew is left but blood and guts…

The next story, “A Relic of the Empire,” features a mystery rooted as much in biology as physics. Doctor Richard Schultz-Mann is exploring when he is captured by a group that fancies themselves pirates, led by a man who calls himself “Captain Kidd.” They have been preying on Puppeteer trade, but are now in hiding, having discovered the secret location of the Puppeteer homeworld…

“At the Core” brings Beowulf Shaeffer back for yet another mission serving the puppeteers. They have developed a new hyperdrive, which barely fits in the largest of their General Products hulls, but is orders of magnitude faster than existing hyperdrives. As a publicity stunt, they want Shaeffer to travel to the core of the galaxy, a round trip that with this ship should take about 50 days… Shaeffer moves the ship to the gap between spiral arms, where stars are less dense, to make better progress. And what he finds at the center of the galaxy will transform civilization throughout Known Space.

In “The Soft Weapon,” Jason Papandreou and his wife Anne-Marie detour from their trip to Jinx to visit the unusual star Beta Lyrae. They are accompanied by a puppeteer named Nessus (who we will meet once more in Ringworld). They detect a stasis field, a relic of the extinct slavers, and go to retrieve it. Unfortunately for them, it is a trap, set by a crew of piratical kzin, the fierce cat-like beings that have repeatedly been at war with humanity. They find a strange, multipurpose weapon, and to win their freedom, must unravel its many properties. And along the way, they find puppeteers are not as helpless as most believe…

I would highly recommend this collection to anyone who enjoys a satisfying, science-based short story. Reading this collection reminded me of just much I enjoy Larry Niven’s early work, particularly when his focus was on shorter works and scientific puzzles.

Our previous coverage of Larry Niven includes:

The Golden Age of Science Fiction: The 1973 Skylark Award: Larry Niven by Rich Horton (2019)

The Golden Age of Science Fiction: Convergent Series by Steven H Silver (2019)

Birthday Reviews: Larry Niven’s Convergent Series by Steven H Silver (2018)

It’s Large: Ringworld by Fletcher Vredenburgh (2017)

The Magic Goes Away by Fletcher Vredenburgh (2013)

Neutron Star was published as a paperback original by Ballantine Books in April 1968. It is 285 pages, priced at $0.75. The cover artist is unknown. It has been reprinted in many editions over the past 55 years, including a digital edition from Spectrum Literary Agency in 2013.

See all our recent Vintage Treasures here.

I have the copy with the Rick Sternbach cover- a classic! I had no idea the stories in it were as old as they were– one of the strengths of Nivan’s writing, in my opinion.

It is a great collection. I think “Relic of Empire” really stands out for me.

Adrian,

I’m with you — I had no idea Neutron Star was originally published in the 60s until I began collecting old paperbacks, and realized the Sternbach version wasn’t the original one.

Niven’s stories held up well for decades, I thought.

I wouldn’t count James H. Schmitz as a Pohl discovery, at least not exclusively. His best known story, “The Witches of Karres,” appeared first in Astounding as a novelette; his very popular later Telzey Amberdon stories were published in Analog in the 1960s. At least that part of his oeuvre was published by Campbell, and I think the development of his career can be credited in substantial part to Campbell.

Bill,

You’re absolutely right. Even through the 60s, Campbell was still developing new writers (like Schmitz, Anne McCaffrey, Mack Reynolds, and many others). James H. Schmitz sold his first story to Campbell in 1943 (for Unknown).

I just couldn’t resist including some of the Campbell writers Pohl published over the years (even Heinlein, long after Heinlein had quit Astounding for good). There were a lot of writers who seemed to outgrow Campbell, and Pohl was able to give them new markets to grow into.

I read a lot of Niven, back in the day. I’ve said before that there were certain authors I never read (e.g. Heinlein) because I thought of them as old-fashioned. Then there were authors who were at the cutting edge, like Gibson. I re-read some Niven last year and thought he stood up pretty well, even if characterisation was never his strong suit. A gap of thirty or so years did give me an interesting perspective on him in that he seems to have straddled two different worlds. A lot of his stories have pulp ’50’s DNA but they are also recognisably ‘modern’ in the context of the times – ie, late 60’s/early 70’s. To cite one example, the Draco Bar stories are a very Fifties conceit, but you would never mistake them for being written in the Fifties. Or at least, I don’t think so!

That’s a fine summation of Niven, and it jives with my assessment of his career. He had the love of adventure and exotic locales that were a staple of ’50s-era sci-fi, but his style was more contemporary. He also explored the cutting edge of science (well, ’60s-era science), and his famous ringworld is one of the classic Big Dumb Objects that came to exemplify a particular brand of SF that put exploration front and center. Numerous authors appropriated the ringworld over the next five decades.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Big_Dumb_Object

A. B. Chandler is another one.

Though you wrote “nurturing and publishing an extraordinary array”, you seem to imply that Pohl “discovered” Chandler.

Chandler, was in fact nurtured and published by Campbell, starting in 1944 with “This Means War”. Chandler would stop in at Astounding’s offices whenever he made port in NYC and Campbell encouraged him to submit.

Not to take anything away from Fred Pohl (who I knew somewhat and worked with on a World Future Society meeting and lecture): he was a member of First Fandom and a Futurian, an early and very influential club that included Wollheim, Asimov, Blish, Knight, Kyle, Bok, and others and of whom I think a very strong case can be made collectively contributed more to the development of both the genre and Fandom than any other single individual you care to name, including Gernsback and Campbell.

Steve,

Yup, you are correct. William Stoddard made the same point about James H. Schmitz (another Campbell discovery) above. I didn’t mean to imply that Pohl discovered all these authors (and that list I gave is by NO means a comprehensive count of the many authors he DID discover.)

What I was trying (clumsily) to say was that there were plenty of authors who abandoned Campbell when his idiosyncrasies became too much to bear (Heinlein is probably the most famous example, but there were many), and for them Pohl was an editor who could nurture their talent with a less restrictive market.

My Niven story: I discovered him in high school and had pretty much a complete collection of the then-extant Known Space books (everything through Ringworld Engineers). One summer, we went on a family vacation camping in state parks on Minnesota’s North Shore, and all I brought to read was the Known Space books, which I plowed through in the first half of the trip, so I had NO CHOICE but to immediately go back and start rereading them (for lack of anything else to read).

And after that trip I became an INVETERATE overpacker of books every time I traveled, although these days the Kindle makes that a lot easier to accommodate.

(And that seems to me like a pretty decent stopping place, at least for the Known Space books — I wasn’t thrilled with the subsequent Ringworld novels, in part because Niven kept trying to retrofit contemporary understandings of science and advanced tech — nanobots, e.g. — into a setting that was so firmly grounded in that late 60s/70s era.)

Joe — funny you should say that. In just that last few days I’ve heard from a couple of dedicated SF readers who said they picked up the habit of reading science fiction by bringing a suitcase of books on vacation in their teens. It’s definitely something I did as I was discovering paperback sci-fi in the 70s. I’m sensing a shared communal experience here. 🙂

Larry Niven!

My God that’s a blast from the past. (As a youngster, I used to empty the library of 6 sci-fi – and later – fantasy books at a time. By the time I was in my 20’s, I was accumulating my own library. While I never got into short story compilations (apologies, they never appealed), I was an avid novel reader, and absolutely loved Ringworld. (early 80’s, I think). I remember the cover caught my eye, as it had warped/curved writing, positioned up in the clouds

Haven’t read/re-read him for years. (BUT – that’s gonna change. I made a promise 🙂 )