A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Patrick Murray on Cross-Genre Confusion, and Supernatural Westerns

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

(Gat — Prohibition Era term for a gun. Shortened version of Gatling Gun)

Last week was part two of fellow Robert E Howard Foundation Award-winner John Bullard’s look at Robert E. Howard’s humorous Westerns. Earlier this summer, Pulp maven (and fellow Sherlock Holmes afficionado) William Murray revealed right here in this column, that Dashiell Hammett did not actually write “The Diamond Wager/” Will, who has written about Doc Savage, and The Spider, for A (Black) Gat in the Hand, is back at it again.

Will – who has written THE look at Western pulps – Wordslingers: An Epitaph for the Western – takes us into the world of Weird Westerns. It’s no surprise that Pulp editors were leery of ‘crossing the streams’ for these types of stories. Read on!

Cross Genre Confusion

In the beginning, the pulp magazine was an undifferentiated product.

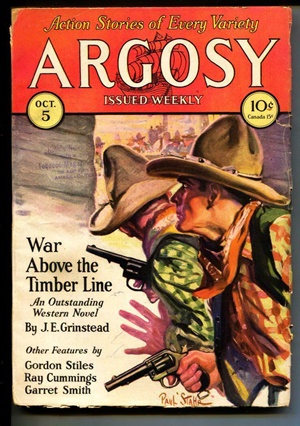

Starting with the first of its type, The Argosy, it was essentially a colorful cornucopia of fiction, much of it belonging to no particular category. Stories of city, farm, and tenement life were common. Yarns set in the half-tamed West were not always gunsmoke sagas, but simply narratives set in the contemporary West. Historical tales were also common. As were simple homespun comedies. Many were quasi-adventure stories of men at their work. Thus we often discover coal mining episodes, off-field yarns, and Mountie exploits.

Over time, the recognizable genres overtook the slice-of-life stories of early America. Before long, the average issue of Argosy or All-Story, or any of the other early all-fiction magazines would typically feature a Western story, a detective story a love or romance story, as well as tales tying to the different sports categories, and of course what they called “different“ or “off-trail“ stories. These could be yarns that fit into no recognizable category, or ones that bent the conventions of popular fiction, as it was at that time. As often as not, the more fantastic stories were usually science fictional, but occasionally ghost stories.

Street & Smith was the first publisher to break away from the old fiction straitjacket. In 1915, they turned their Nick Carter dime novel series into Detective Story Magazine. Buffalo Bill Stories became Western Story Magazine in 1919. After Frank Merriwell dime novels went out of fashion, he resurfaced in Street & Smith’s Sport Story Magazine. Love Story Magazine also followed. These titles prospered. Not all such specialized periodicals were successful. Street and Smith‘s The Ocean, dedicated exclusively to sea stories, flopped a year after its 1907 debut. Perhaps it might have done better if it had been called something more exciting, like Sea Stories, which S&S put out with greater success in 1922.

Street & Smith was the first publisher to break away from the old fiction straitjacket. In 1915, they turned their Nick Carter dime novel series into Detective Story Magazine. Buffalo Bill Stories became Western Story Magazine in 1919. After Frank Merriwell dime novels went out of fashion, he resurfaced in Street & Smith’s Sport Story Magazine. Love Story Magazine also followed. These titles prospered. Not all such specialized periodicals were successful. Street and Smith‘s The Ocean, dedicated exclusively to sea stories, flopped a year after its 1907 debut. Perhaps it might have done better if it had been called something more exciting, like Sea Stories, which S&S put out with greater success in 1922.

In 1919, they also launched a printed concoction called The Thrill Book, which was neither fish nor fowl. The twice-monthly magazine was an eclectic mixture adventure, fantasy and what passed for science fiction during the post-World War I period. For a long time, this rare title was considered to be the first venture in the direction of a science-fiction magazine. In truth, even though science fiction was a significant presence in its pages, as were ghost and pure fantasy yarns, for the most part The Thrill Book was just another odd fiction magazine, a little more quirky and offering the off-trail yarn in every issue.

In the early 1920s, other publishers jumped in. Almost overnight, there were a number of Western and detective and romance titles. One publisher launched Ranch Romances, which was a hybrid of the Western and the romance fields. It was one of the few combination titles to flourish.

Pulp readers preferred their fiction to be pure and genre-specific.

As Margaret MacMullen observed in her 1937 Harper’s Bazaar essay, “Pulps and Confessions,”

“There are ‘pulps’ that contain nothing but railway stories. The ‘Westerns’ never move the scene away from a ranch. In the sports magazines are all kinds of sport, from boxing to polo; but the issue is seldom confused by the introduction of even minor crime and detection, and only rarely by a subordinate love interest.”

Weird Tales made its debut in 1923, but sold so poorly that it struggled for years and imitators were few and equally problematic.

The first pure Science Fiction magazine, Amazing Stories, was brought out in 1926. Like Weird Tales, it inspired few imitators at first.

In 1928, Street & Smith hired a young editor named Paul Chadwick to helm a new title, one that would be a little more focused than The Thrill Book, but not quite a science fiction magazine. Its title is not known, but a market description of what it was looking for was printed:

Street and Smith are buying stories for a new magazine, which will use “fast-moving war, aviation, Western, and outdoor adventure stories.“… Paul Chadwick, the editor, makes this statement:

“I am going to run a lot of rather far-fetched stories of the Jules Verne type, and I’d like every story in the magazine to have a sensational and slightly fantastic touch. The regulation Western story wouldn’t do. The Western stories I buy must have some particularly novel plot, or a fantastic tone, and they must be above the average in suspense, excitement, and speed. A lost tribe of Indians, a mysterious treasure out in the desert on the desert, the discovery of a remnant of an ancient tribe of cliff dwellers––that is a sort of thing I mean. Or perhaps a bandit, who disguises himself with phosphorus—‘the ghost bandit.‘

There will also be pseudo-scientific stories, and perhaps some dashing young hero could use scientific methods in a western story. The main thing is to have thrills and excitement from start to finish, though sometimes suspense will make a story just as thrilling as swift action. They should be little, if any woman or sex interest. The story should all be focused around one hero––preferably, a young man. But this is not a juvenile magazine, and the stories must be strong and convincing, so no, no matter how far-fetched.“

This announcement was printed in The Author and Journalist, June 1928.

There is no doubt that this was going to be a fantastic magazine, even if it wasn’t going to be devoted strictly to science fiction and fantasy. It may have been Street & Smith’s response to both Weird Tales and Amazing Stories, but on its own conservative terms. But it sounds like a confusion of genres bound by desire to be out of the box.

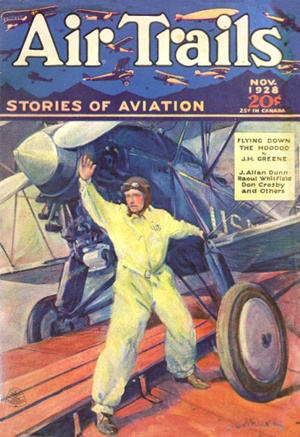

Instead of launching this experimental title, Street & Smith killed it. Maybe finding appropriate stories to fulfill its editorial vision proved too daunting. Instead, they made Chadwick the editor of their latest entry in the hot new aviation field, Air Trails. It was a safer bet.

In addition to stories of the pioneer sky lanes, Air Trails carried a series by J. Allan Dunn that was much more fantastic than the rest of the lineup. Set in the near future, it revolved around a pilot named “Ace” Ainsworth, who had exotic adventures and flew aircraft a generation ahead of the 1920s. Don Crosby was the byline Dunn used. These stories were futuristic without being unabashedly science fictional. Probably the first of these were purchased for the nameless fantastic magazine.

In addition to stories of the pioneer sky lanes, Air Trails carried a series by J. Allan Dunn that was much more fantastic than the rest of the lineup. Set in the near future, it revolved around a pilot named “Ace” Ainsworth, who had exotic adventures and flew aircraft a generation ahead of the 1920s. Don Crosby was the byline Dunn used. These stories were futuristic without being unabashedly science fictional. Probably the first of these were purchased for the nameless fantastic magazine.

But the standout character in Air Trails was one created by Robert J. Hogan. Hogan who had once spent time on an Arizona ranch and stumbled upon a wild new idea. His name was Smoke Wade. He was a commissioned cowboy who flew during World War I in a dappled spad painted to resemble a pinto pony. In addition, Wade wore his Stetson in the cockpit, with his six–gun on his hip.

There had been a brief vogue of cowboy aviators in the years after Charles Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic in 1927. Modern stories of cowboys and their aircraft. Often set in the American West. These modern cowpokes patrolled their vast spreads and herded their cattle from on high. “Cowboy-air” was the name editors gave to this new sub-genre. But no series characters built around the idea, and the novelty quickly wore off. Consequently, this hybrid air-hero type began fading away in 1929.

Smoke Wade, who debuted in 1931’s “Wager Flight,” was the last gasp of the breed. Apparently, Air Trails readers never read Western pulps, and so had never come across an hombre of his caliber. They loved Smoke Wade. Enough to keep Air Trails going hot for about a year or two.

After Air Trails was canceled, Smoke Wade reappeared in Popular Publications, Daredevil Aces, where he continued for many years. He was the last survivor of the brief innovation that mated the cowpoke with the air ace, and the only one remembered today.

The Western field was one that was most resistant to innovation. Editors were willing to publish stories set in the then-modern West, where brave buckaroos switched from mustang to Model-T effortlessly, but they preferred the historic West. Yet they would just as soon writers left out any mention of Indians. For some reason, readers of that time had low tolerance for Indian characters, no matter which side of the good-guy/bad-guy fence they rode.

Another taboo was the supernatural story. In fact, many genre magazines looked askance at ghost or horror stories. But Western editors especially abhorred them.

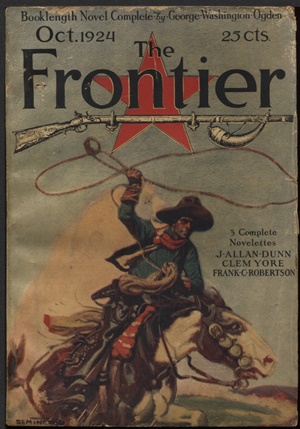

In one 1925 writer‘s magazine, editor Ralph R. Perry recounted a revealing anecdote about going through the slush pile. It ran as follows:

One of your fellow editors drops a story on your desk.

“I wish you’d read this,” he requests cautiously.

“We can’t use that on a bet,” you report later. “Why, it’s a ghost story. We found out what our readers think of ghost stories when we––”

“I know,“ he explains patiently. “But don’t you think it would be a pretty good yarn if he told it right? It’s laid in the West, you see, and he seems to know the country. I’m going to write him a letter. I think he can do stuff for us.”

“Go ahead!” you grin, with a unconcern born of many disillusionments.

Perry was assistant editor on The Frontier. The anecdote comes from his article, “Crashing the Editorial Gate” which was printed in The Author and Journalist, March, 1925.

Perry was assistant editor on The Frontier. The anecdote comes from his article, “Crashing the Editorial Gate” which was printed in The Author and Journalist, March, 1925.

I would like to know what story precipitated such a ruckus. I probably never will.

This was no fluke of one editor, or his pulp house’s policies. The anti-ghost phobia was industry-wide.

“There are certain taboos which affect virtually the whole field, and these should be avoided in the plot,” cautioned writer Arch Joscelyn. “Indian stories, ghost or horror stories, tales depending mostly on atmosphere and psychological action—these are a few.”

Writer-editor Richard A. Martinsen echoed this in 1931:

“A yarn with the least trace of the supernatural, bogus or real, used as a frame-up by the villain or as fact, is out for West.”

Genre confusion was a strict pulp no-no. Any editor who attempted to tamper with or dilute the conventional genre formula was soon set straight by his audience.

According to Margaret MacMullen:

“When one of the periodicals devoted to young love inquired in its pages whether an occasional deviation from the happy-ending rule would be acceptable, the answer came in a torrent of pathetic, self-revealing letters, all on the theme that ‘life is sad enough as it is.’ These people were not arguing an abstract, literary principal. They really cared.”

Early in his long career, prolific Westerneer S. Omar Barker wrote a supernatural Western. He had very little luck with it. This is what he recalled years later:

“One short story of mine, ‘Back Before the Moon,’ was in the mail off and on for seven years, was turned down seventy-five times, and finally was bought for $74 by Strange Tales—which promptly kapooted with the issue in which it appeared! This off-trail opus raises its ghostly head again in the WWA anthology, Great Ghost Stories of the West.”

From 1925 to 1932 is seven years. Maybe “Back Before the Moon” was the rejected story mentioned by Perry. Chronologically, it fits perfectly.

It would be 22 years before Barker sold another manuscript with a supernatural element to a Western magazine. “The White Mustang” appeared in Triple X Western in 1954. However, it was not a story, but only a poem.

Spooky Westerns were so rare that most of the contents of the 1969 anthology Great Ghost Stories of the West had been written in that same decade. The only exceptions were Barker’s.

Another such effort, 1990’s Western Ghosts: Spine-Chilling Stories from the American West, plucked tales from magazines ranging from 1909 to 1983, and out of periodicals as disparate as Cosmopolitan, The Saturday Evening Post, and Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. But none from Western fiction magazines. In fact, few of its stories were set in the 1800s.

Probably the most prolific pulpster who wasn’t tied to a single magazine was Arthur J Burks. He grew up in the Washington State area which, while technically the West, apparently was not Western enough for pulp editors.

Burks lamented, “I was born in the West, was eighteen years old when I left it. I have managed, by dint of much effort, to sell only four westerns.’”

He did sell one spooky specimen, but to his main market, Weird Tales. “Ghosts of Steamboat Coulee” was the title. It appeared in the May, 1926 issue.

Robert E Howard was comfortable writing straight Westerns and horror stories alike. So it’s probably no surprise what he sometimes combined those genres. “The Horror from the Mound” was one such. Once again, WeirdTales printed it in May, 1932. In July 1933, the Unique Magazine ran Howard’s “The Man of the Ground.” “Old Garfield’s Heart” appeared in the December, 1933 issue. These Western horror narratives were unlikely to appear anywhere else. Yet near the end of his life, Howard successfully placed “The Dead Remember” with Argosy, which printed it in its August 15, 1936 issue.

Another prolific wordsmith is known to have landed a supernatural story in a regulation Western pulp magazine. L. Ron Hubbard sold “Shadows From Boothill” in Wild West Weekly in 1940.

Another prolific wordsmith is known to have landed a supernatural story in a regulation Western pulp magazine. L. Ron Hubbard sold “Shadows From Boothill” in Wild West Weekly in 1940.

In a note to the editor, the author wrote: “Hope your readers like Shadows from Boot Hill. The Old West was superstitious in the extreme and … reeks with more fantasy than The Arabian Nights.”

For a long time, I suspected that the story was written at the request of the editor in an effort to shake up the magazine‘s contents during a period when Western magazine sales were struggling to find fresh cowboy cliches. But according to the surviving correspondence, Hubbard simply wrote it, submitted it, and the story was accepted. Westerns pulp were suffering s severe circulation slump in 1938-40, so this was probably the result of desperate editor. Although WWW’s ramrod, John Burr, asked readers if they wanted more, I doubt he ever ran another spook story.

And Hubbard never wrote another. Not even for Unknown, where something like “Shadows from Boothill” might have been a better fit.

It seems that everyone who toiled for the pulp Western magazines and wrote a supernatural Western story was lucky to sell it, if he did. And if he did, apparently, he never bothered to write another. There was no market for such a concoction. It was editorial poison.

That, however, changed during the latter part of the pulp era.

In the pages of—of all titles—Real Western, a long-running series of supernatural Westerns were regularly printed. Most of these were supernatural in the sense that the protagonist encountered characters out of Greek Mythology, yes, in the Wild West. Lon Williams was the byline. For a time it was suggested this might have been editor Robert W. “Doc” Lowndes himself, since he was a writer as well as an editor.

But no, Lon Williams was a real person, a Tennessee lawyer who moonlighted writing fiction. And his supernatural series went on for some 36 installments until they petered out, along with the rest of the pulp field. The story titles tell the tale: “Ghost, Ride with me!”, “The Haunted Town,” “Wizard of Forlorn Gap” and “The Three Fates” were among them.

By that time, I imagine, pulp editors had dealt with every conceivable cliché and retread idea in the Western field, and were desperate to do something different. In this case, Williams’ Deputy Marshall Lee Winters series obviously met with the approval of 1950s readers. The stories ran regularly from 1952 to 1958, with the final pair popping up in Double Action Western in 1959.

This makes me wonder had some enterprising editor early on stuck out his neck and run a similar series, if that might not have eventually resulted in a specialized crossbreed pulp magazine title, something like Two-gun Ghost Western.

Probably not. But it would be amusing had it been the case.…

“There are “pulps” that contain nothing but railway stories. The “Westerns” never move the scene away from a ranch. In the sports magazines are all kinds of sport, from boxing to polo; but the issue is seldom confused by the introduction of even minor crime and detection, and only rarely by a subordinate love interest.

—Margaret MacMullen

“Pulps and Confessions”

Prior Posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2023 Series (8)

Back Down those Mean Streets in 2023

Back Down those Mean Streets in 2023

Will Murray on Hammett Didn’t Write “The Diamond Wager”

Dashiell Hammett – ZigZags of Treachery

Ten Pulp Things I Think I Think

Evan Lewis on Cleve Adams

T,T, Flynn’s Mike & Trixie (The ‘Lost Intro’)

John Bullard on REH’s Rough and Ready Clowns of the West – Part I (Breckenridge Elkins)

John Bullard on REH’s Rough and Ready Clowns of the West – Part II

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2022 Series (16)

Asimov – Sci Fi Meets the Police Procedural

The Adventures of Christopher London

Weird Menace from Robert E. Howard

Spicy Adventures from Robert E. Howard

Thrilling Adventures from Robert E. Howard

Norbert Davis’ “The Gin Monkey”

Tracer Bullet

Shovel’s Painful Predicament

Back Porch Pulp #1

Wally Conger on ‘The Hollywood Troubleshooter Saga’

Arsenic and Old Lace

David Dodge

Glen Cook’s Garrett, PI

John Leslie’s Key West Private Eye

Back Porch Pulp #2

Norbert Davis’ Max Latin

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2021 Series (8)

The Forgotten Black Masker – Norbert Davis

Appaloosa

A (Black) Gat in the Hand is Back!

Black Mask – March, 1932

Three Gun Terry Mack & Carroll John Daly

Bounty Hunters & Bail Bondsmen

Norbert Davis in Black Mask – Volume 1

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2020 Series (19)

Hardboiled May on TCM

Some Hardboiled streaming options

Johnny O’Clock (Dick Powell)

Hardboiled June on TCM

Bullets or Ballots (Humphrey Bogart)

Phililp Marlowe – Private Eye (Powers Boothe)

Cool and Lam

All Through the Night (Bogart)

Dick Powell as Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar

Hardboiled July on TCM

YTJD – The Emily Braddock Matter (John Lund)

Richard Diamond – The Betty Moran Case (Dick Powell)

Bold Venture (Bogart & Bacall)

Hardboiled August on TCM

Hardboiled August on TCM

Norbert Davis – ‘Have one on the House’

with Steven H Silver: C.M. Kornbluth’s Pulp

Norbert Davis – ‘Don’t You Cry for Me’

Talking About Philip Marlowe

Steven H Silver Asks you to Name This Movie

Cajun Hardboiled – Dave Robicheaux

More Cool & Lam from Hard Case Crime

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2019 Series (15)

Back Deck Pulp Returns

A (Black) Gat in the Hand Returns

Will Murray on Doc Savage

Hugh B. Cave’s Peter Kane

Paul Bishop on Lance Spearman

A Man Called Spade

Hard Boiled Holmes

Duane Spurlock on T.T. Flynn

Andrew Salmon on Montreal Noir

Frank Schildiner on The Bad Guys of Pulp

Steve Scott on John D. MacDonald’s ‘Park Falkner’

William Patrick Murray on The Spider

John D. MacDonald & Mickey Spillane

Norbert Davis goes West(ern)

Bill Crider on The Brass Cupcake

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2018 Series (32)

George Harmon Coxe

Raoul Whitfield

Some Hard Boiled Anthologies

Frederick Nebel’s Donahue

Thomas Walsh

Black Mask – January, 1935

Norbert Davis’ Ben Shaley

Norbert Davis’ Ben Shaley

D.L. Champion’s Rex Sackler

Dime Detective – August, 1939

Back Deck Pulp #1

W.T. Ballard’s Bill Lennox

Day Keene

Black Mask – October, 1933

Back Deck Pulp #2

Black Mask – Spring, 2017

Frank Schildiner’s ‘Max Allen Collins & The Hard Boiled Hero’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Campbell Gault

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: More Cool & Lam From Hard Case Crime

MORE Cool & Lam!!!!

Thomas Parker’s ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’

Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part One)

Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part Two)

William Patrick Maynard’s ‘The Yellow Peril’

Andrew P Salmon’s ‘Frederick C. Davis’

Rory Gallagher’s ‘Continental Op’

Back Deck Pulp #3

Back Deck Pulp #4

Back Deck Pulp #5

Joe ‘Cap’ Shaw on Writing

Back Deck Pulp #6

The Black Mask Dinner

There are some outstanding names in the ‘New Pulp’ field, but William Patrick Murray’s probably stands above them all. Along with Doc Savage, Will has written Tarzan and The Spider. And he’s quite the Sherlock Holmes writer. Short stories, comic books, radio plays, nonfiction essays and books – Murray has done it all. He created The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl for Marvel Comics, and his collection of essays on Doc Savage, Writings in Bronze, is a must read. As I mentioned in the introduction, Wordslingers – An Epitaph for the Western, is THE guide to Western Pulps. I love a good book introduction, and Murray has written some fine ones for Steeger Books. Visit his website Adventures in Bronze.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE DEFINITIVE guide to Conan. He also organized 2023’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, and XXXIII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

Interesting. Probably because I like so many genres I never had a problem with cross genre stories.

Howard was one of the innovators of the Weird Western. Another was Rod Serling. The Twilight Zone had a few supernatural stories set in the old West due to having many props and costumes available since Westerns were real popular at the time.

[…] first resource I found for Weird Western online was on Black Gate by Patrick Murray, “On Cross-Genre Confusion and Supernatural Westerns“. While educational entertaining, it really did not help me find much Weird Western fiction I […]