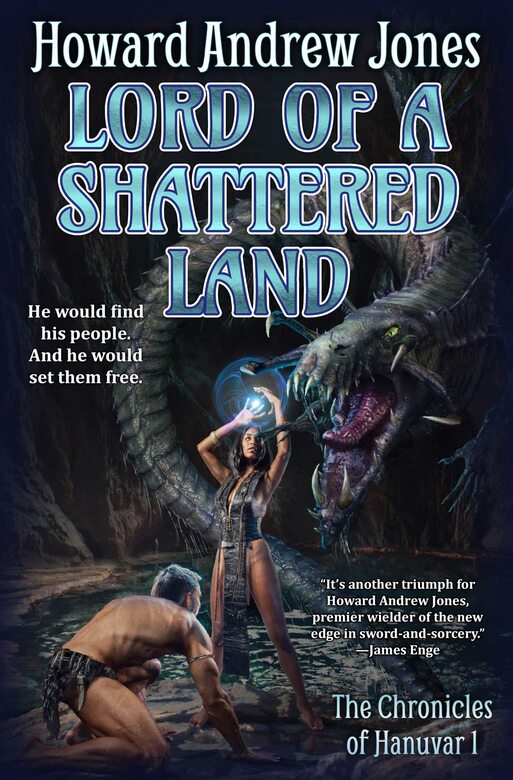

This is Hanuvar’s Moment: Howard Andrew Jones’ Lord of a Shattered Land

Lord of a Shattered Land (Baen Books, August 1, 2023). Cover Art by Dave Seeley

From the beginning, Sword and Sorcery has been an existentialist literature of the outsider. The rogue, the mercenary, the outcast, the criminal: from Conan to Elric, Fafhrd to Corwin of Amber, Jirel of Joiry to Grimnir the Corpse-maker, the S&S protagonist finds themselves at odds with their society, confronted with aggressive meaninglessness and called upon to carve out their own meaning in a chaotic, ever-changing, and often hostile world. This allows them to critique their society, test its values, and even challenge its assumptions. It is an intriguing literary tradition that has been a creative sandbox for several ambitious literary artists.

But this is not how most readers vaguely familiar with the term understand the genre. Sword and Sorcery has a reputation for being puerile and violent male wish-fulfillment fantasy. This stereotype derives from several obscure causes. One major cause might be the 1960s and 70s “Clonan” (Conan + clone) type of Sword and Sorcery, an assembly of several barbarian warriors and their formulaic adventures inspired by the commercial success of the Lancer reprints of Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Cimmerian stories (beginning in 1966 and featuring the famous covers by Frank Frazetta). Though not entirely without entertainment value, this group of works features the adventures of Lin Carter’s “Thongor,” John Jakes’ “Brak the Barbarian,” Gardner F. Fox’s “Kyrik,” and many more.

[Click the images for sword-and-sorcery versions.]

|

|

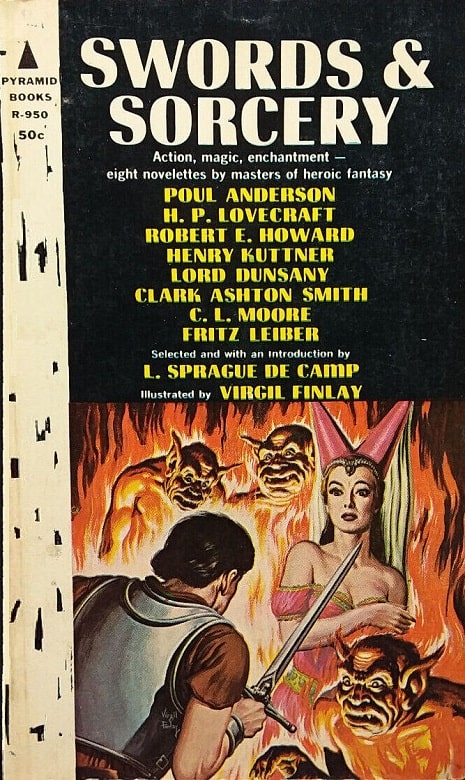

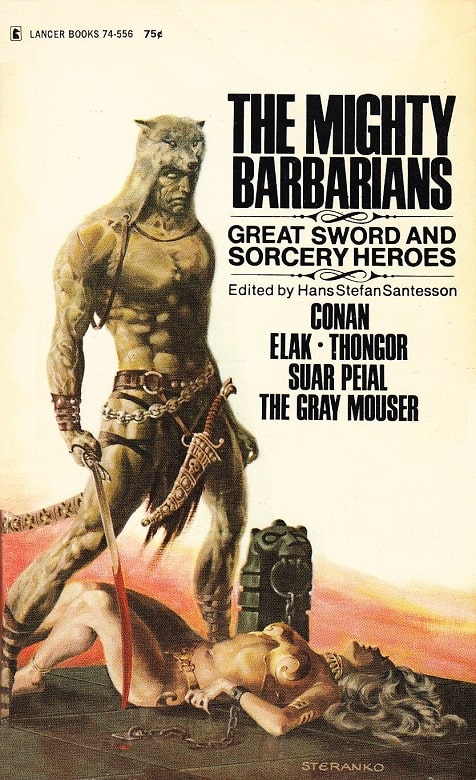

Swords and Sorcery edited by L. Sprague de Camp (Pyramid Books, December 1963), and The Mighty Barbarians

edited by Hans Stefan Santesson (Lancer Books, 1969). Covers by Virgil Finlay and Jim Steranko.

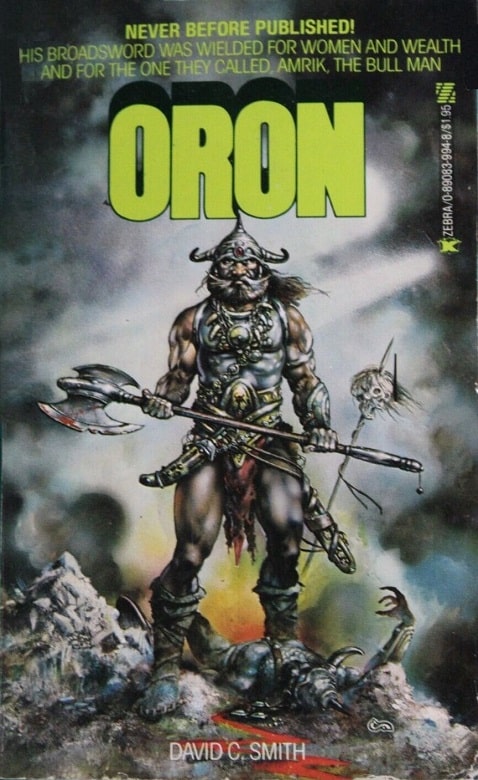

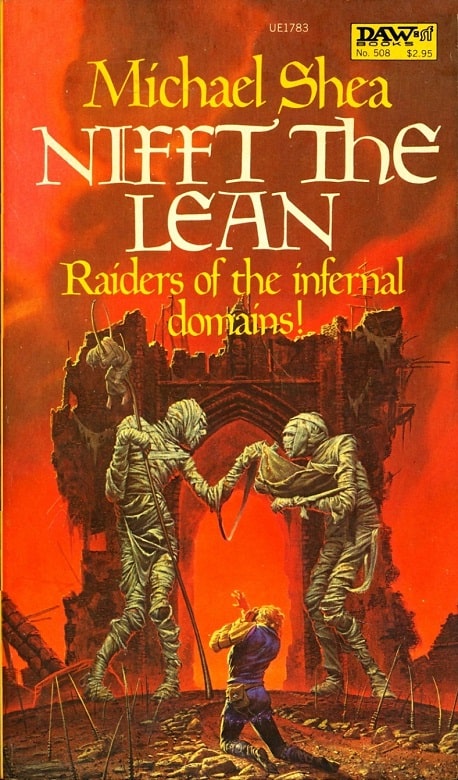

It also saw the creation of Sword and Sorcery’s fundamental literary form, the short story anthology, with the publication of some of the first of its kind, e.g., Swords and Sorcery (1963) edited by L. Sprague de Camp and The Mighty Barbarians (1969) edited by Hans Stefan Santesson. This period of literary activity, despite beginning as a commercial gambit, nevertheless produced several enduring, artistically ambitious works: David C. Smith’s darkly atmospheric Oron (1978), Michael Shea’s lyrical Nifft the Lean (1982), and Karl Edward Wagner’s tales of Kane come to mind. From a certain perspective, the genre was declining by the early 80s, but it still managed to provide an opportunity for literary innovation.

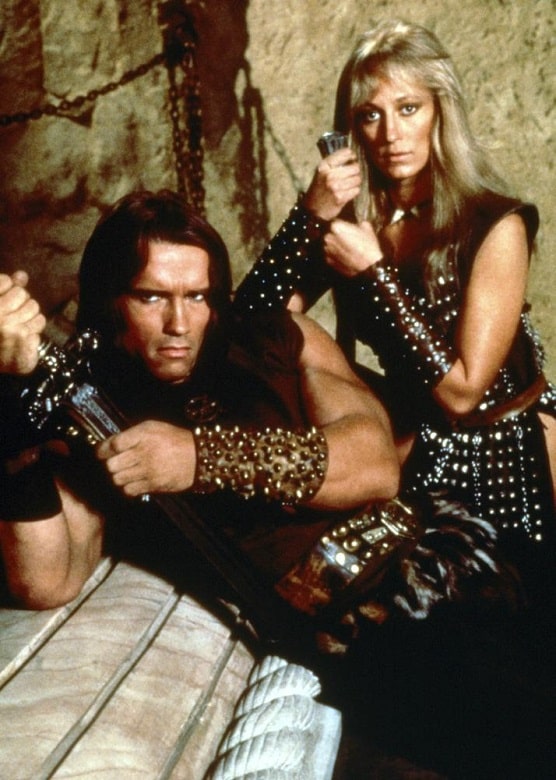

But this wasn’t to be the case for long as another cause of S&S’s reputation for puerility debuted: the box office success of John Milius’ Conan the Barbarian (1982). Opinions vary regarding Arnold Schwarzenegger’s rendering of the eponymous character as well as John Milius’ translation of Robert E. Howard’s pulp tales into a screenplay, but the irrefutable fact is that the film is one of the most influential fantasy films of all time, studied in film schools, imitated by film auteurs such as Robert Eggers, and indelibly embedded in the constellation of S&S pop culture consciousness.

|

|

Oron by David C. Smith (Zebra Books, June 1978), and Nifft the Lean

by Michael Shea (DAW, December 1982). Covers by Clyde Caldwell and Michael Whelan

Alas, just as with the Lancer Conan series, the Milius’ masterpiece spawned several sub-par imitators. Who can forget The Sword and the Sorcerer (1982), Deathstalker (1983), Conan the Destroyer (1984), The Warrior and the Sorceress (1984), and the pièce de résistance, Deathstalker II (1987)?

And it gets worse: as the 1980s proceeded, Tor fantasy published a series of middling Conan pastiche novels. From 1982 to 2003, over 40 of these books were published (of varying quality). Despite excellent covers by several celebrated fantasy artists, most aspired to be nothing less than fan ephemera, despite a few standouts (John C. Hocking’s Conan and the Emerald Lotus (1995) winning the laurel for the best of that series). So, we have a clear and dark pattern, like an ash mandala or blood writ pattern of demonolatry: literary innovation followed by commercial success followed by pale imitation followed by accelerated stereotyping. Sword and Sorcery can’t catch a break. Or can it?

Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sandahl Bergman in Conan the Barbarian (1982)

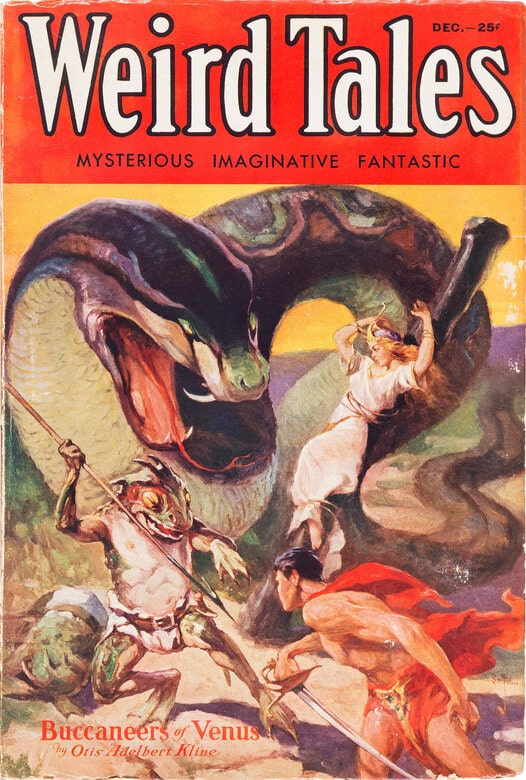

Fans of Sword and Sorcery know that the tragically obscured and nuanced heart of the genre is not locatable in the Clonan period or in the (often hilarious) B-movie tropes of the 1980s. Sword and Sorcery’s thematic core is not located in bulging thews and biceps, phallic swords or blood sprays, or swaying hips. It’s in the existential fantasy literary tradition of the autonomous outsider protagonist inaugurated by Robert E. Howard in 1932 with the publication of the first Conan the Cimmerian story, “The Phoenix on the Sword,” in Weird Tales. This combined the grittiness of historical verisimilitude with the artful unreality of cosmic horror pioneered by H.P. Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith while bringing in an interwar ethos of social anomie and the retreat of traditional sureties.

Moreover, Sword and Sorcery isn’t, as many believe, the literary fungal outgrowth of fantasy role-playing games, the mere exuda of Gary E. Gygax’s wonderful Appendix N. It’s more than that. It is central to genre fiction and literary history. It is an interwar pulp tradition that links the works of C.L. Moore, Fritz Leiber, Jack Vance, Michael Moorcock, Charles Saunders, Michael Shea, Roger Zelazny, David C. Smith, Scott Oden to perhaps the oldest form of storytelling ever: the epic, i.e. cultural touchstones such as Gilgamesh, the Odyssey, the Viking sagas, Beowulf, and many more.

And S&S is still alive and evolving today, which is the topic of the rest of this article: Sword and Sorcery’s emerging present, poignantly captured by the example of the tenacious Howard Andrew Jones, a modern S&S writer whose newest work, Lord of a Shattered Land, does nothing less than set the record straight and map a territory for future S&S writers to explore.

The December 1932 issue of Weird Tales, featuring the

first appearance of Conan in “The Phoenix on the Sword”

If the tale of Sword and Sorcery as a genre seems to be a tragedy of literary innovation followed by uninspired imitation and critical confusion, then I’m here to tell you that the story is not over yet. It’s not a tragedy, it’s not a comedy, it’s a tragicomedy with ups and downs, and our current hero is Howard Andrew Jones (or, to be more precise, his newest Sword and Sorcery hero, Hanuvar). In order to explain why, let me first briefly clarify what I understand to be the key aspects of Sword and Sorcery and why Hanuvar is so exciting in this context.

First, Sword and Sorcery is about outsider protagonists: rogues, criminals, outcasts, barbarians, heretics, i.e. people who exist on the margins of a dangerous society that is often hostile toward them. Second, Sword and Sorcery is a presentist genre. Unlike high fantasy in the mode of J.R.R. Tolkien, it is not concerned with nostalgia, restoring the broken world, nor is it concerned with the future, establishing utopia or the return of a king. Sword and Sorcery is, in contrast, concerned with the ever present now. Its protagonists always find themselves on the razor’s edge of becoming, bridging the past and the future.

This is why violent battles are so predominant in the genre. Battle is intrinsically exciting and intriguing; anyone who has read a superhero comic understands that violence can be aestheticized. But the true reason that battle is central to Sword and Sorcery is that it puts the protagonist on the boundary between life and death. No one is more alive, more present, than when their very life is at stake. Finally, Sword and Sorcery tales are about escapism, strategically inoculating the self from the stimuli of the so-called “real world,” and in this way, it is supremely artful and literary, pure story, a genre of deliberate distraction and interiority, entertainment; in a word, is it ludic.

David Carradine in The Warrior and the Sorceress (1984)

Defining Sword and Sorcery is often a fool’s errand, a kind of fan ritual, akin to a skipping record, but definition is sometimes required to bring into focus difference and innovation. How can we know something is new until we have defined what has come before? I believe Howard Andrew Jones’ Lord of a Shattered Land represents an important moment for the genre, a signal of where it is and where it can go next, and I’ve defined Sword and Sorcery as a literature of the outsider, the present moment, and escapism above to bring into focus how Lord of the Shattered Land is doing intriguing work.

First, let’s consider the element of the “outsider protagonist.” Hanuvar, the protagonist of Lord of a Shattered Land, is not a barbarian, mercenary, rogue, or outcast. In fact, the city-state from which he hails, Volanus, was highly civilized, perhaps an apex of civilization, akin to an Atlantis or Gondor, an aspirational polity. But Volanus was destroyed in a great war, conquered by a militaristic and ethno-nationalist regime, the Dervan Empire. Hanuvar, then, is not an outsider because he is a barbarian, a foreigner coming into a civilized land. He is an outsider because his society has been destroyed. He is profoundly defeated and finds himself in enemy territory, surrounded.

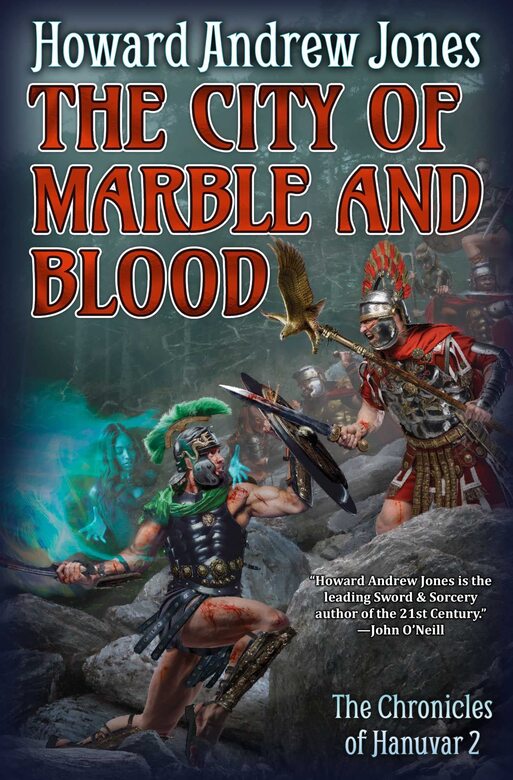

The City of Marble and Blood, Book Two of The Chronicles of Hanuvar

(Baen Books, October 3, 2023). Cover by Dave Seeley

Next, let’s consider the element of Sword and Sorcery’s presentism. This is where Jones’s subtle didacticism comes in, his moral vision: Hanuvar has every reason to give up. His beloved city has been destroyed, its ground has been sowed with salt, its beautiful towers tumbled, its temples desecrated; several of his family members are dead or missing; his people have been butchered or sold into slavery. Hanuvar could sit around in a tavern telling tales of the beauty of the Volanus that was; or, he could make grand plans for the re-forging of a new and better Volani Empire. But Hanuvar doesn’t try to do either of these things. He refuses soporific nostalgia and the mirage of utopia. Instead of dreaming into the past or flaming a warpath into a better, idealized future, Hanuvar soberly acknowledges his situation and sets about concretely and deliberately picking up the pieces. Without giving away any of the plot, the first steps Hanuvar takes are not to re-establish an army or seek vengeance; it is to find his kith and kin, to figure out if they’re OK, and to liberate them.

Finally, let’s consider the third aspect: escapism. Many are suspicious of the idea of literary escapism today. Escapism seems to suggest social irresponsibility or self-indulgence. Harkening back to the golden age of science fiction, some people want their fiction to be intentionally activist, engineered to “move the needle,” as it were; and so writers often set out to write clearly political fiction that comments on and critiques contemporary concerns. I think this idea sets up a reductive false binary. Works that are deliberately escapist, that seek to inoculate the reader or auditor from the toxic stimuli of the real world, aren’t necessarily irrelevant to contemporary concerns. Instead, their relationship with the real world is just more complex, oblique, obscured by way of allegory and something like a political unconscious.

The idea that escapist works are, paradoxically, relevant to contemporary society applies importantly to Lord of a Shattered Land. For example, Hanuvar seems changed by his traumatized past filled with brutal war, ubiquitous conflict, and ethnic and cultural rivalry. Hanuvar is a man who has fought several wars, killed countless enemies, and sent several compeers to their deaths by his official orders. Hanuvar has experienced the quintessential war story and knows how it always begins and always ends: it begins with cheering and it ends with holocaust. And so, often, his approach to conflict, time and again, is to de-accelerate tension, to try to understand the perspective not just of his allies but also his enemies. Some of the most enthralling moments in the novel are where Hanuvar holds back his wrath and dares to see his enemy as human.

Hanuvar is one of our first deeply compassionate Sword and Sorcery heroes, showing the wisdom of someone who has realized, via the crucible of war, what is most important in our brief lives: family, friends, safety, and shared humanity. Hanuvar has every reason to be seething with desire for revenge against the injustices wrought by the cruel and brutal Dervans; but there is a deep wisdom to the character, palpable in almost every scene that includes him, that allows us to see through the senselessness of violence, the insanity and misery of sustained and brutal conflict predicated on the poisonous idea of a dehumanized Other. Hanuvar, a true lord of a shattered land, paradoxically fights for dialogue, conversation, the end of conflict (or at least its attenuation). One only has to read the second chapter in the novel, “The Warrior’s Way,” to learn this is a worldview that is seasoned by deep sorrow — and yet! — still affirming of life. This is very different from the “Clonans” and the B Sword and Sorcery movies of the 1980s, the unfair stereotypes that have sometimes plagued Sword and Sorcery.

Hanuvar’s superpower, if you will, is that he understands the dangerous consequences of extreme tribalism, of pure hatred, of culture war, of the dark process of dehumanization that predicates all wars. But the question becomes: is this ethic a deliberate commentary by Jones on the political tensions that are endemic to American culture and politics today? Is Jones, in the manner of a pamphleteer, decrying dividedness, tribalism, racism, the various wars being fought around the globe, the diverse phobias the plague us all in their every Protean forms? Very personally speaking, I believe Jones is too much of a committed literary artist for that. His prose is a master class in narrative craft demonstrating economic description, keen pacing, precise dialog, and vivid imagery. But is this sword and sorcery novel just an aesthetic exercise? I truly don’t know. But it is this strategic ambiguity that is a source of the strength of literary escapism. Such works, by keeping the real world at bay, give us breathing space to contemplate the current moment in a different way. They allow you to come to your own conclusions.

My hope is that Lord of a Shattered Land will demonstrate to new readers that Sword and Sorcery fiction is more than just puerile male wish-fulfillment fantasy. Since 1932, the genre has endured; a core group of dedicated fans and writers have understood what adventure fantasy stories featuring an outsider protagonist acknowledging the present moment in an unreal world can do. In this way, Howard Andrew Jones’ new novel, Lord of a Shattered Land, is a timely corrective. To the extent that we all live in a shattered land, this is Hanuvar’s moment.

Jason Ray Carney is a Lecturer in Popular Literature at Christopher Newport University. He is the author of the academic book, Weird Tales of Modernity (McFarland), and the fantasy anthology, Rakefire and Other Stories (Pulp Hero Press). He edited Savage Scrolls: Thrilling Tales of Sword and Sorcery for Pulp Hero Press and is an editor at The Dark Man: Journal of Robert E. Howard and Pulp Studies and Whetstone: Amateur Magazine of Sword and Sorcery. His last article for Black Gate was a review of John Shirley’s A Sorcerer of Atlantis.

I really enjoy the concept of Escapism as a key ingredient in Sword&Sorcery literature. Your discussion reminds me of Prof. Tolkien’s famous dismissal of those who scoff at Escapism: “Who are the people most opposed to Escapism? Jailors!”, along with his longer quote about the duty of a literary prisoner of war to escape: “If we value the freedom of mind and soul, if we’re partisans of liberty, then it’s our plain duty to escape, and to take as many people with us as we can.” You keep excellent company, Mr. Carney.

Thanks! I’ve read Tolkien’s comments on escapism. He’s so insightful on that topic. Thanks for reading my review.

That was an eloquent and impassioned defense and celebration of sword and sorcery as a noble and misunderstood genre and a hailing of HAJ as a modern champion of its best virtues.

It’s good (and rare) to see a review as well informed, incisive and positive as this one on any piece of current fiction, much less one focused on the oft-scorned niche sub-genre of sword & sorcery.

As a guy with S&S somehow inscribed into my genes, thanks.

Great article. Perhaps sword and sorcery can only really abide in a society with existentialist/nihilist ethos. As such, it will always be consumed with the moment and therefore violent. Hanuvar, on the other hand, is not nihilistic nor existentialist. He is modern and not postmodern. Hence violence but for a deeper purpose. So Howard Andrew Jones book is more a rejection of nihilism and thereby a significant deviation within the genre.