A (Black) Gat in Hand – Hammett & Zigzags of Treachery (My Intro)

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

(Gat — Prohibition Era term for a gun. Shortened version of Gatling Gun)

I went to Pittsburgh’s Pulp Fest 2023, weekend before last. It was a fun time, with lots of cool chatting. I’ve got some pics and I’ll try to do a post next week. Steeger Books awlays rolls out their Summer releases at Pulp Fest. Volume Two of Rex Sackler (D. L. Champion) is out. I wrote about Sackler here – those stories are SO much fun! And the first Bill Lennox (W. T. Ballard) book is out. Lennox was one of my first essays for this series, and I’m a huge fan.

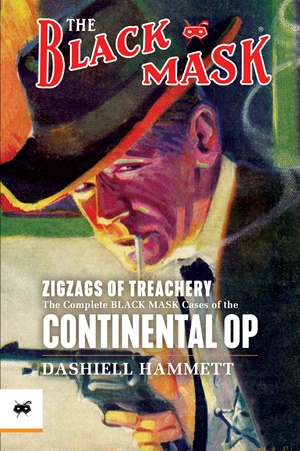

I’m biased, but I was most excited about the first volume of The Continental Op. I wrote the intro for Zigzags of Treachery, and I’m kicking off the new run with it. If you like it, maybe check out the book. The Continental Op is one of the best private eyes in the genre.

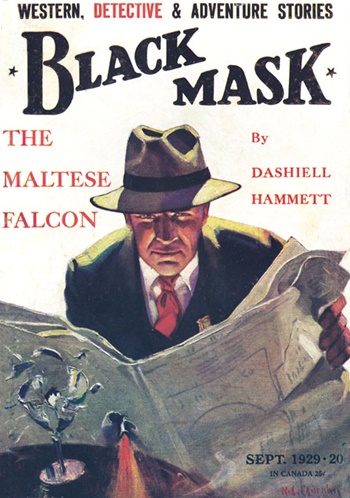

It’s got a terrific cover from Henry C. Murphy. Murphy – who died of cancer at only age 45 – drew the well-known image of Sam Spade used for the first installment of The Maltese Falcon. So, here’s my intro. I’m pretty pleased with it.

Black Mask. Dashiell Hammett. Joseph ‘Cap’ Shaw. Those three names are inextricably linked together as the bedrock of the hardboiled school of mystery fiction. The October 1, 1923, issue of Black Mask included “Arson Plus,” the first story featuring a nameless detective known as The Continental Op.

Earlier that May, Carroll John Daly’s Three Gun Terry Mack had become the first hardboiled dick, and he was followed a month later by Race Williams. The immensely popular Williams was the prototypical gun-slinging Western cowboy who solved every problem with hot lead, but now wearing a suit and transplanted to the urban setting of city streets. Written in heavy-handed, over-the-top prose, Williams relied on guns and massive amounts of testosterone, leaving the city littered with corpses.

As Williams says in the first story, “You can’t make a hamburger without grinding up a little meat.” And he certainly didn’t lose any sleep over it: “But my conscience is clear. I never bumped off a guy what didn’t need it.” Non-stop violence and a total lack of remorse sums up Race Williams. As does poor grammar.

An employee of The Continental Detective Agency (thus the name), Hammett’s The Continental Op functioned as an actual detective who used a mix of brains, determination to complete the job at hand, old fashioned hard work, and a healthy dose of courage. His was a more viable blueprint for an enduring legacy. Hammett started out using the name Peter Collinson (‘Peter Collins’ was slang for a nobody), but quickly switched to his own name with the Op stories.

So, now we’ve got Black Mask, and Dashiell Hammett writing about The Continental Op. There’s a misconception that Cap Shaw made Hammett, and that Shaw turned Black Mask into a hardboiled magazine (Shaw himself helped foster the latter misconception, though he also downplayed it as well).

But just as Daly came before Hammett, – though the second became the greater – two men edited The Op and steered Black Mask into the hardboiled genre before Shaw took the helm. Shaw undeniably turned Black Mask into THE definitive hardboiled pulp, but Hammett wrote over half his Op stories before Shaw arrived. Shaw didn’t create Hammett the writer – though he did resurrect Hammett the writer. More on that in the next volume.

Nine of the eleven stories in this collection came under the oversight of George W. Sutton, who was a writer of automobile and motorboat articles for various publications. Sutton was three months into his editorship when he published “Arson Plus.” At that time, Black Mask was a mix of Westerns, weird menace, ghost stories, and not-so-hardboiled detective stories. Hammett and Daly truly were the first to walk down those mean streets.

Nine of the eleven stories in this collection came under the oversight of George W. Sutton, who was a writer of automobile and motorboat articles for various publications. Sutton was three months into his editorship when he published “Arson Plus.” At that time, Black Mask was a mix of Westerns, weird menace, ghost stories, and not-so-hardboiled detective stories. Hammett and Daly truly were the first to walk down those mean streets.

In March of 1924, the Sherlock Holmes story “The Adventure of the Creeping Man,” and “Murder on the Links” (the second Hercule Poirot novel), were published. That was the state of the mystery story in England. “Arson Plus” had a rural feel to it, but it was no grotesque mystery, or a golf course murder committed with a paper knife. And it most certainly did not feature a brilliant, eccentric, unconventional private detective solving the case by finding bizarre clues.

This was a reasonably intelligent private eye using logic and shoe leather to figure out who used arson to kill a reclusive man. And this private eye did not blast his way through the story, leaving a trail of corpses, as Race Williams did. In fact, we don’t even hear mention of the Op carrying a gun until the fifth story.

The plot in “Arson Plus” could easily have been from a Holmes or Poirot story: ‘“But Holmes, Thornburgh’s man, Coons, saw him in the window, engulfed in flames.” My friend gave me an enigmatic smile. “Did he indeed, Watson?” Holmes could be positively infuriating at times.’

But there’s none of that here. The Op, aided by a smart but lazy policeman, doggedly works the trail, asking questions and looking for clues. It’s not about the specific type of clay on someone’s shoe, or the angle of a mirror after a bullet had shattered it – Hammett used his experience as a Pinkerton to write more realistic detective fiction. As Raymond Chandler wrote of Hammett: “He made some of it up; all writers do; but it had a basis in fact; it was made up out of real things.”

Someone traveled by train? ‘Tracing baggage is no trick at all, if you have the dates and check numbers to start with – as many a bird who is wearing somewhat similar numbers on his chest and back, because he overlooked that detail when making his getaway, can tell you…’

A few stories later, the Op relates, ‘99 percent of detective work is a patient collecting of details – and your details must be got as nearly first-hand as possible, regardless of who else has worked the territory before you.’ These stories foreshadow the police procedural.

The Oxford English Dictionary describes ‘fiction’ as “Literature in prose form. Describing imaginary events and people.” The very first words in Raymond Chandler’s The Simple Art of Murder are, “Fiction in any form has always intended to be realistic.”

In a June 15, 1923, letter to the editor in Black Mask, Hammett says that he doubts “…it would be possible to build a character without putting into it at least something of someone the writer has known.” Then he says that he had encountered the blackmailing plot (of “The Vicious Circle”) as a detective. This was months before he created the Op and wrote “Arson Plus”

So, Hammett was using his real-world Pinkerton experiences for his stories, making them much more realistic than Carroll John Daly’s stories. While he wasn’t writing dry lessons on detection dressed up as fiction, he still went to great pains to defend the realism.

So, Hammett was using his real-world Pinkerton experiences for his stories, making them much more realistic than Carroll John Daly’s stories. While he wasn’t writing dry lessons on detection dressed up as fiction, he still went to great pains to defend the realism.

Hammett included a letter in the same October 15 issue that included “Slippery Fingers.” He mentioned that the Berkeley chief of police had made an unrelated statement about fingerprints which essentially made Hammett’s story unrealistic. He defended his story, saying that experts would agree it could and had been done, and that “successful experiments were made with it by the experts at the Leavenworth federal prison.”

He wasn’t done yet. The April 1924 Black Mask issue included an article from a Mr. Reeves, which stated three infallible ‘facts’ about fingerprints and does not appear to have been supportive of Hammett’s story. In the June 1925 issue, Hammett wrote a letter, almost one-third as long as the entire “Slippery Fingers” story, in response to Reeves’ article. Hammett doesn’t rant, but he’s clearly rankled. He discusses each of the three facts in depth, and goes on to talk about scientific and circumstantial evidence. This is his second Black Mask response defending his use of fingerprints in the story.

Hammett didn’t turn his Pinkerton cases into boring detective stories. Or, as Chandler wrote, “He made the detective story fun to write, not an exhausting concatenation of insignificant clues.” (And his prose wasn’t as snobbish as Chandler’s would be, as evidenced by that quote)

Realism (both professionally and philosophically) were the bedrock of Hammett’s mystery fiction. And at least early on, he was going to great lengths to defend that realism.

“Crooked Souls” And “Slippery Fingers” (apparently two-word titles were all the rage) followed “Arson Plus” two weeks later, and Hammett’s presence in Black Mask was firmly established.

Hammett also wrote a letter to the editor which went with “Crooked Souls.” The story was about the kidnapping of a grown daughter, and that same month Hercule Poirot would solve the kidnapping of a young son. But that’s the only thing in common between “The Adventure of Johnnie Waverly“ and Hammett’s story.

They are good examples of the contrast between the ‘country manor sensibilities’ of Britain’s Golden Age of Detection Fiction, and the urban street style of the newly developing American hardboiled school.

The bad guy gets the drop on the Op in the final scene of “It,” and as the Op puts up his hands, he explains, “I didn’t have a pistol with me, not being in the habit of carrying one except when I thought I was going to need it…”

You could easily find at least one quote in every single Race Williams story that is the polar opposite of this.

In the fifth story, “Bodies Piled Up,” we finally see the Op carrying a gun. Two very bad guys are shooting it out in an Italian restaurant. The customers have all fled, and the Op has hidden behind a wall. “I had my gun out, but I was playing a waiting game…I kept away from the bullets that were flying around as best I could and waited.”

Williams would never take cover and let the bad guys shoot it out. He seemed to exist to commit violence and mayhem.

Race Williams and the Op were contemporaries. There is no denying that Black Mask readers were titillated by the violence and fast-paced action of Daly’s stories. It was said that Daly’s name on the cover was good for a fifteen (I’ve also seen twenty) percent bump in sales for that issue. And it’s the same type of two-fisted violence that would make Mickey Spillane the genre’s best-selling author ever (with a healthy serving of sex added in). There’s no denying it played a huge part in Black Mask’s increasing popularity.

In one story, the Op says that if he were a movie actor or the like, he would have jumped out of a window, caught the neighboring roof, and made an acrobatic escape. But he didn’t do any of that because dangling in space didn’t appeal to him. He immediately follows with “Then I did another not-at-all heroic thing.” Rather than stalking his dangerous captors (he is unarmed, himself) in a dark house, he turns on the lights, lights a cigarette, and waits for them on the bed.

The hardboiled school was literally being birthed, and two very different babies were being born. In 1930, Daly was handily chosen as Black Mask readers’ favorite author. Erle Stanley Gardner was second, with Hammett third. Daly’s stories were more popular in the short run, but Hammett has long been considered the far better writer.

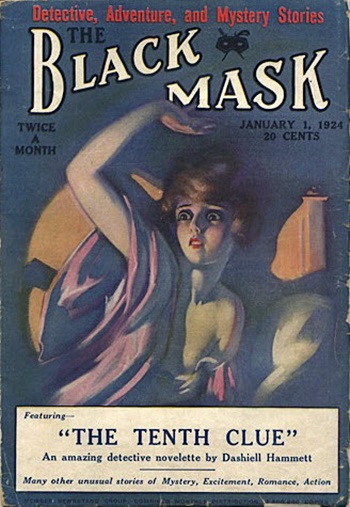

“Bodies Piled Up” has one of my favorite openings for a hardboiled PI story, and the gun play at the end was a step towards more action in Hammett’s stories. The next story (the sixth), “The Tenth Clew,” was as long as the previous two stories combined. Story eight, “Zigzags of Treachery,” would be even longer, and Hammett was moving towards novella, and then novel, -length storytelling.

“Bodies Piled Up” has one of my favorite openings for a hardboiled PI story, and the gun play at the end was a step towards more action in Hammett’s stories. The next story (the sixth), “The Tenth Clew,” was as long as the previous two stories combined. Story eight, “Zigzags of Treachery,” would be even longer, and Hammett was moving towards novella, and then novel, -length storytelling.

Unlike his more famous counterpart, Sam Spade, the Op works hand-in-hand with the police in many of his cases. He might as well be a de facto member of the force in these first few stories. He is all but partnered up with Sacramento deputy McCump in the first story. He frequently works with San Francisco detective-sergeant O’Gar, with whom he had “hit it off excellently.” In “The Tenth Clew,” O’Gar asks someone a question that puzzles the Op, and the latter asks him to loosen up and fill him in. O’Gar obediently does so. There’s none of the friction we often see in many private detective stories, as with Spade and Lieutenant Dundee.

Hammett did not recycle his short stories to turn them into novels, as Raymond Chandler would later do (to great success!). But it seems pretty obvious that he revisited “Night Shots” (Story seven) when he cranked out his third and final Sam Spade short story, “They Can Only Hang You Once.”

In “Zigzags of Treachery,” Hammett uses the Op to give the four rules of successful tailing. And we also see a more hardboiled Op. While undercover, he provokes his mark, who angrily pulls a gun on him. The Op is not passive this time: ‘Firing from my pocket, I shot it out of his hand. “Now behave!” I ordered.’

The Op then goes on to logically explain that while it looks impressive, it’s not really such a big deal to make that shot, and why. As Hammett instructs the reader on both shadowing and shooting, the realism and his experience are always in play. He included a letter in the same issue as this story, talking more about shadowing and his experiences with it as a Pinkerton.

In these early stories, Hammett’s belief in civic corruption, and the cynicism that would become hallmarks of his hardboiled stories, aren’t nearly as present as they would be later. But there was an ongoing umbrella of realism over the Op from the very start.

We also see that the Op can be cold-blooded in “Zigzags of Treachery.” He lightly explains it away, but it’s a first look at this type of hard-bitten morality – something that Race Williams would have dismissed with a comment like “They make their own beds. I just tuck them in at night. Permanently!”

“One Hour” sees a return to the shorter story. San Francisco attorney Vance Richmond, the client in “Zigzags of Treachery,” brings another case. The Op pulls a gun on a suspect but finds himself quite outnumbered in a fierce melee. Hammett puts us inside the Op’s head as he desperately struggles to survive, using both his fists and his wits. And even a cuspidor! It’s a tense action scene in a fast-paced story that entirely takes place in only one hour.

“One Hour” appeared in the April 1, 1924, issue, which was the first for new editor Philip Cody. But given the timing, it’s reasonable to assume that it was written for and accepted by Sutton.

Cody took over from Sutton, and immediately changed the tone of Black Mask. It would more resemble the magazine of the Cap Shaw Era, with a leaner, harder style. Hammett’s own writing had steered in that direction, and there was more of an edge to his work for Cody. We’ll talk about Cody’s impact on Black Mask, Hammett, and the hardboiled school, in the next volume. A mention here of Harry North, who was assistant editor to both Sutton and Cody, and stayed on with Shaw. He played an important role in the development of the hardboiled genre, and I’ll try to talk a little more about him in the future.

Hammett is widely regarded as the greatest hardboiled writer of them all (yes, I know there’s a Chandler camp – just go with me here). He didn’t start out as the best, right from story one. While these early stories weren’t always overly exciting, they were realistic.

Hammett, who had attended Munson’s Business College (that always makes me think of Tim Robbins’ ‘Muncie College of Business Administration’ in the terrific The Hudsucker Proxy), was learning the craft of writing fiction and incorporating his experience as a Pinkerton detective. It was that combination which shaped the newborn hardboiled school. Black Mask was full of melodramas, and Carroll John Daly had started writing his outlandishly violent detective stories. Hammett was grounding the genre while he learned more about plotting and characterization by rapidly pushing out stories.

And we see the growth – the low-key, laconic pace and lack of danger in “Arson Plus” is a mere memory by the action-oriented “Bodies Piled Up.” And as we arrive at “The House in Turk Street,” Hammett is about to master the intriguing hardboiled PI story.

His style had been developing with nine Op stories in only seven months. And he had been gradually ratcheting up the gunplay and the violence under Sutton. From the very first story with Cody at the helm, you could drop the ‘gradually.’

For me, it’s in “The House in Turk Street” (which was adapted for the 2002 Samuel L. Jackson movie, No Good Deed) where we really see the classic Hammett for the first time. The characters, the pace, the tension, the plot elements: he was moving from learning to improving to the verge of mastering.

The young punk, Hook, presages The Maltese Falcon’s Wilmer (though he’s no gunsel); Elivra gives us a future glimpse of Brigid O’Shaughnessy; and the short, fat, British, Tai Choon Tau brings to mind Casper Gutman: albeit, a Chinese version. It’s bonds instead of a bird, but there’s even a Mexican standoff with a line similar to Joel Cairo’s “But we certainly have you.” It’s a compact, exciting story that takes place in less than a day, in one house. I think it would make a good stage play.

Elvira is Hammett’s first femme fatale. Edna (“Zigzags of Treachery”) is a seasoned grifter, but she’s just a supporting player. Elvira carves her presence as the kind of hard, seductive, wily female that leaves a trail of despair and disaster throughout the genre, playing on men’s affections for her own gain. And as we are to learn, the Op wasn’t finished with her yet.

“The Girl with the Silver Eyes” is a sequel to “The House in Turk Street,” at twice the length. Together, they are about as long as the first four Op short stories combined. Hammett was moving towards the long form that would result in four serialized novels – at least three of which are regarded among his best work.

“The Girl with the Silver Eyes” is the final story in this book, and it appeared in the same June 1924 issue as Daly’s “The Red Peril.” Compare the two stories. Daly was still writing the same one-dimensional character, and the same ultra-violent action. Hammett had continued to use his real-world Pinkerton experiences while honing his writing skills, and his work was notably improved from the first Op tale.

It is rightly considered one of his best stories. Burke Pangburn (client), Jeanne Delano (silver-eyed girl), and Porky Grout (criminal informant) are all well-drawn characters, with depth. Delano takes the femme fatale seen in “The House in Turk Street” a level further and Hammett just doesn’t tell us that men cannot resist her – he shows it in dramatic fashion. The Op faces his greatest emotional test so far in dealing with her.

Porky is a snitch. Today’s cop shows would call him a CI (criminal informant). He’s a stool pigeon in Hammett’s slang. He’s been mentioned before, but we meet him for the first time and get the full view:

Porky is a snitch. Today’s cop shows would call him a CI (criminal informant). He’s a stool pigeon in Hammett’s slang. He’s been mentioned before, but we meet him for the first time and get the full view:

“I don’t know a single thing that could be said in his favor. He was a coward. He was a liar. He was a thief, and a hophead. He was a traitor to his kind and, if not watched, to his employer…

Detecting is a hard business, and you use whatever tools come to hand. This Porky was an effective tool if handled right, which meant keeping your hand on his throat all the time and checking up every piece of information he brought in.”

More practical advice from Hammett, via the Op. I find Porky, and how he interacts with the Op – and how it reflects another relationship – one of the most interesting aspects of this collection.

Hammett did not start out submitting perfect stories. Three of the first four begin with the kind of heavy-handed info dumps that are common to new – or not good – writers. Lots of exposition that buries the reader with all the relevant information to get the story going. The short story requires a deft hand to avoid this – check out Lawrence Block and Ed McBain to see two masters at it. And you have time to go in the kitchen and make a sandwich while the crook gives a long-winded, convoluted explanation of EVERYTHING near the end of “Zigzags of Treachery.”

But Hammett was honing his craft, and these early stories were different from anything else being written. Daly was also doing the hardboiled private eye, but Hammett was doing it cleaner, leaner, and tighter. With realism and characterization; not simple shoot-em-up action.

George Sutton preferred Hammett’s realistic, well-written private eye stories to the ultra-violent, simplistic action yarns of Carroll John Daly. Philip Cody urged Hammett to pack in more action, and the stories would improve. But Cody would publish him less frequently; deny his request for a raise (even though Erle Stanley Gardner offered to take a pay cut to help fund Hammett): and would be the reason that Hammett quit Black Mask. Fortunately, Cap Shaw would coax Hammett back and build Black Mask around the author.

We’ve seen so many hardboiled PI stories and movies over the past hundred years: We need to remember that Hammett was a literary pioneer. Nobody had done with the mystery story what he was doing in each issue of Black Mask. Carroll John Daly was also covering new ground, but not nearly as well.

Hammett’s first eleven Continental Op stories don’t constitute his greatest hits. But something special was happening, story by story. By the time he completed his first two stories for Phil Cody, Hammett had laid the groundwork for a genre that still influences the mystery field a century later.

Prior Posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2023 Series (1)

Back Down those Mean Streets in 2023

Will Murray on Hammett Didn’t Write “The Diamond Wager”

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2022 Series (16)

Asimov – Sci Fi Meets the Police Procedural

The Adventures of Christopher London

Weird Menace from Robert E. Howard

Spicy Adventures from Robert E. Howard

Thrilling Adventures from Robert E. Howard

Norbert Davis’ “The Gin Monkey”

Tracer Bullet

Shovel’s Painful Predicament

Back Porch Pulp #1

Wally Conger on ‘The Hollywood Troubleshooter Saga’

Arsenic and Old Lace

Arsenic and Old Lace

David Dodge

Glen Cook’s Garrett, PI

John Leslie’s Key West Private Eye

Back Porch Pulp #2

Norbert Davis’ Max Latin

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2021 Series (8)

The Forgotten Black Masker – Norbert Davis

Appaloosa

A (Black) Gat in the Hand is Back!

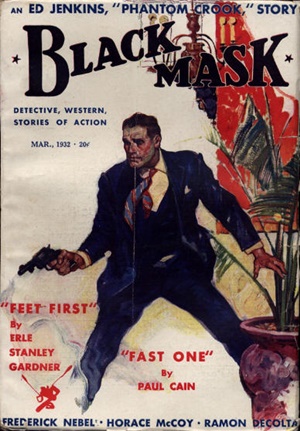

Black Mask – March, 1932

Three Gun Terry Mack & Carroll John Daly

Bounty Hunters & Bail Bondsmen

Norbert Davis in Black Mask – Volume 1

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2020 Series (19)

Hardboiled May on TCM

Some Hardboiled streaming options

Johnny O’Clock (Dick Powell)

Hardboiled June on TCM

Bullets or Ballots (Humphrey Bogart)

Phililp Marlowe – Private Eye (Powers Boothe)

Cool and Lam

All Through the Night (Bogart)

Dick Powell as Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar

Hardboiled July on TCM

YTJD – The Emily Braddock Matter (John Lund)

Richard Diamond – The Betty Moran Case (Dick Powell)

Bold Venture (Bogart & Bacall)

Hardboiled August on TCM

Norbert Davis – ‘Have one on the House’

with Steven H Silver: C.M. Kornbluth’s Pulp

Norbert Davis – ‘Don’t You Cry for Me’

Talking About Philip Marlowe

Steven H Silver Asks you to Name This Movie

Cajun Hardboiled – Dave Robicheaux

More Cool & Lam from Hard Case Crime

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2019 Series (15)

Back Deck Pulp Returns

A (Black) Gat in the Hand Returns

Will Murray on Doc Savage

Hugh B. Cave’s Peter Kane

Paul Bishop on Lance Spearman

A Man Called Spade

Hard Boiled Holmes

Duane Spurlock on T.T. Flynn

Andrew Salmon on Montreal Noir

Frank Schildiner on The Bad Guys of Pulp

Steve Scott on John D. MacDonald’s ‘Park Falkner’

William Patrick Murray on The Spider

John D. MacDonald & Mickey Spillane

Norbert Davis goes West(ern)

Bill Crider on The Brass Cupcake

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2018 Series (32)

George Harmon Coxe

Raoul Whitfield

Some Hard Boiled Anthologies

Frederick Nebel’s Donahue

Thomas Walsh

Black Mask – January, 1935

Norbert Davis’ Ben Shaley

D.L. Champion’s Rex Sackler

Dime Detective – August, 1939

Back Deck Pulp #1

W.T. Ballard’s Bill Lennox

Day Keene

Day Keene

Black Mask – October, 1933

Back Deck Pulp #2

Black Mask – Spring, 2017

Frank Schildiner’s ‘Max Allen Collins & The Hard Boiled Hero’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Campbell Gault

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: More Cool & Lam From Hard Case Crime

MORE Cool & Lam!!!!

Thomas Parker’s ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’

Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part One)

Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part Two)

William Patrick Maynard’s ‘The Yellow Peril’

Andrew P Salmon’s ‘Frederick C. Davis’

Rory Gallagher’s ‘Continental Op’

Back Deck Pulp #3

Back Deck Pulp #4

Back Deck Pulp #5

Joe ‘Cap’ Shaw on Writing

Back Deck Pulp #6

The Black Mask Dinner

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE 5-star reviewed, Definitive Guide to Conan. He also organized 2024’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, and XXXIII, and an upcoming volume.

He writes introductions to pulp collections and novels from Steeger Books, and has appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

The usual professional and excellent overview of Steeger Books new offering. I admit to being a bit surprised by their offering as a dream came true a few years back with the complete one volume collection of the Big Book of the Continental Op however I liked your overview as well. Written as a fan and a lover of the old pulps it’s always a pleasure to read your insights.

Thanks! I also have Otto Penzler’s ‘Big Book.’

Steeger owns the rights to most Black Mask stuff (I know that ESG is one exception), and I think they wanted to have their own copies of Hammett, out. That’s my guess.

[…] (Black Gate): “You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a […]