Talking Tolkien: Philosophical Themes in the Silmarillion – by Joe Bonadonna

We kicked off Talking Tolkien with Joe Bonadonna, and he’s back! After looking at religious themes in The Lord of the Rings the first time around, it’s philosophical ones in The Silmarillion. Joe does the heavy lifting – I’m just a pretty face. As with his first essay, he wades into pretty deep waters. Joe has guested for my ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ Pulp series, and I’m thrilled he wanted to Talk Tolkien. He even recruited two of our contributors. Read on, and thanks, Joe!

We kicked off Talking Tolkien with Joe Bonadonna, and he’s back! After looking at religious themes in The Lord of the Rings the first time around, it’s philosophical ones in The Silmarillion. Joe does the heavy lifting – I’m just a pretty face. As with his first essay, he wades into pretty deep waters. Joe has guested for my ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ Pulp series, and I’m thrilled he wanted to Talk Tolkien. He even recruited two of our contributors. Read on, and thanks, Joe!

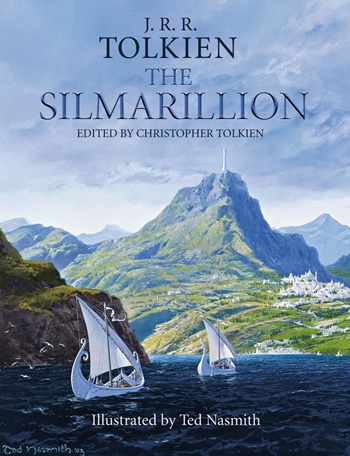

First, I want to reiterate that I am most definitely not an expert on Tolkien’s writings and his history of Middle-earth. Naturally, I’ve read The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion, as well as Smith of Wooton Major, Farmer Giles of Ham, and The Children of Hurin. But I haven’t read anything else Tolkien wrote. Thus, I’ll only be scratching the surface here.

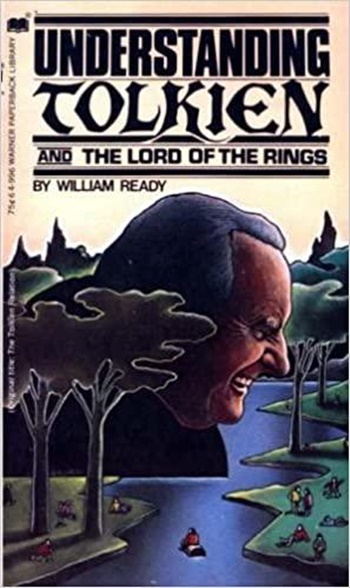

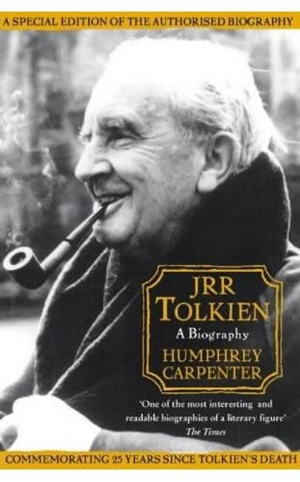

My sources used in research, from which I quoted passages, are: Ruth S. Noel’s The Mythology of Middle-Earth, Robert Foster’s The Complete Guide to Middle-Earth, Paul H. Kocher’s Master of Middle-Earth, William Ready’s Understanding Tolkien, Humphrey Carpenter’s Tolkien: The Complete Biography, and the Tolkien Gateway website, as well as The Hobbit, the appendices in The Return of the King, and The Silmarillion itself. Please note: although the titles of Kocher’s, Noel’s and Foster’s books use a capital E for “earth,” I will use Middle-earth as Tolkien himself did. All that being said, I just wanted to clear the air so you good folks who are reading this will know that I am by far no scholar or expert on all things Tolkien. I’m just here to share an old college essay with you.

As so many of us know, besides his own fertile imagination, Tolkien drew upon a wide array of inspirations and influences, including language, Christianity, mythology, archaeology, ancient and modern literature, and personal experience. He was inspired primarily by his profession, philology, and the study of Old English literature. There is something in Tolkien’s The Silmarillion that goes beyond fantasy. What he has given us is, as I see it, a prehistory mythos of our world, a lost and forgotten history; in many ways it reads like the Bible, filled with the lore and legends of early Middle-earth. Yet the depth of Tolkien’s work lies not in his understanding of mythological and theological themes, but in the subtle way he draws upon philosophical concepts of the Idealist school of thought. Considering that Tolkien was a devout Catholic, I still wonder why there is no mention of organized religion in his work. No one prays or goes to visit a church, temple or mosque. Perhaps I have overlooked or forgotten something. Or perhaps in those elder days, there was no need for such things.

Tolkien and Plato

Plato’s world of Ideas comes into play during the creation myth in The Silmarillion. This was called the Ainulindalë, wherein Eru Ilúvatar sang to the Ainur — who were the first and mightiest of beings created by him — the Three Themes concerning his Vision of Eä, which was Creation. “And it came to pass that Ilúvatar called together all the Ainur and declared to them a mighty theme, unfolding to them things greater and more wonderful than he had yet revealed.” The first of these Theme was Eru’s idea of Heaven and Earth, which the Elves called Menel and Arda.

Plato’s world of Ideas comes into play during the creation myth in The Silmarillion. This was called the Ainulindalë, wherein Eru Ilúvatar sang to the Ainur — who were the first and mightiest of beings created by him — the Three Themes concerning his Vision of Eä, which was Creation. “And it came to pass that Ilúvatar called together all the Ainur and declared to them a mighty theme, unfolding to them things greater and more wonderful than he had yet revealed.” The first of these Theme was Eru’s idea of Heaven and Earth, which the Elves called Menel and Arda.

The second Theme was the shaping of Arda, which Eru gave to the Ainur, the Holy Ones, to develop according to his Vision. “The third Theme, in which the Ainur did not participate, dealt with the creation of the Children of Ilúvatar,” who were the Elves, followed by Man himself. Eru alone shaped this Theme, for only he could attain the perfection of his idea; in essence he was perfection. In the Universe of Tolkien, Eru was the One, the Prime Mover: God.

These Three Themes, the Vision of Ilúvatar, were to act as an inspiration for the Ainur, to guide them in their later works. Historically and religiously, the Ainulindalë was also a guide and inspiration for the Elves and Men of Middle-earth, to show them to what lofty heights their works might reach through the shaping and fashioning of their own ideas. Yet another example shows the development of the Three Themes and how they relate to Plato’s three Social Classes.

WISDOM: The Spiritual Wardens of Creation were the Ainur. Eru entrusted them with the first theme because “. . . he made first the Ainur, the Holy Ones, who were the offsprings of his thought, and they were with him before all else was made.” In a way, the Ainur can be interpreted as being Archangels, for they remained in Menel with Eru Ilúvatar, while others of their kind, namely the Valar, chose to leave Menel for a time and enter into the world of Arda.

COURAGE: The Warriors who protected Arda were the Valar. Their task was to make Middle-earth free of evil and imperfections, so it might bring more joy to Ilúvatar. “Within Eä, the Valar were concerned with the completion of Arda, according to their individual knowledge of portions of the Vision,” wrote Robert Foster. If one is to equate the Ainur with the Archangels, then it is only logical to assume that the Valar were Tolkien’s version of Guardian Angels.

MODERATION: The Artisans of Arda were the Elves and Men of Middle-earth. The firstborn were the Elves, and Eru made them “the fairest of all earthly creatures, and they shall have and shall conceive and bring forth more beauty than all my children.” Eru granted the Elves immortality because they were incapable of perpetrating evil. But for Man, Eru decreed that they should have a virtue to shape their lives, and though they must die, Heaven lay open to them, through his grace. “These, too, in their time shall find that all they do rebounds at the end and only to the glory of my work.” In the end, only Man can approach Ilúvatar and come to dwell with him for all eternity. So here Tolkien weaves together a few of Plato’s philosophical ideas with some very basic theology. Above all the events in The Silmarillion stood Eru Ilúvatar, the Creator, the very epitome of Plato’s Philosopher King.

Tolkien and Saint Augustine

If we view Middle-earth as a version of Saint Augustine’s City of Man, then the next step in this extrapolation would be the City of God, as illustrated by Tolkien’s Blessed Realm, a portion of Menel or Heaven. “. . . and it was blessed, for the Deathless dwelt there, and there naught faded nor withered, neither was there any stain upon flower or leaf in that land, nor any corruption or sickness in anything that lived. . .” Also called Aman the Blessed, this realm is isolated from the mortal world by a barrier of darkness, and only the Elves, who are immortal, can voyage there to dwell in the city of Valinor. The Undying Lands, as they were called by Men, was the realm where rested the Spirits of the Dead. Ideally, the Blessed Realm is Paradise, which Man can only attain through dying. But Men at first were envious of the Elves, who did not need to die in order to gain Aman the Blessed.

If we view Middle-earth as a version of Saint Augustine’s City of Man, then the next step in this extrapolation would be the City of God, as illustrated by Tolkien’s Blessed Realm, a portion of Menel or Heaven. “. . . and it was blessed, for the Deathless dwelt there, and there naught faded nor withered, neither was there any stain upon flower or leaf in that land, nor any corruption or sickness in anything that lived. . .” Also called Aman the Blessed, this realm is isolated from the mortal world by a barrier of darkness, and only the Elves, who are immortal, can voyage there to dwell in the city of Valinor. The Undying Lands, as they were called by Men, was the realm where rested the Spirits of the Dead. Ideally, the Blessed Realm is Paradise, which Man can only attain through dying. But Men at first were envious of the Elves, who did not need to die in order to gain Aman the Blessed.

There was one King of Men who thought death an unjust punishment brought about when other Men fell prey to the temptations of the evil Valar, Morgoth, who was also called Melkor, the Great Enemy. Yet it was a Messenger of the Valar who set the King straight. “And you are punished for the rebellion of Men, you say, in which you had no small part, and so it is that you must die. . . And the Doom of Men, that they should depart, was at first a gift of Ilúvatar.” Death only became a grief to Men when they fell under the Shadow of the Great Enemy. Then they believed that, because of their sins, they were surrounded by darkness, which made them afraid to die, thinking they had forfeited Ilúvatar’s gift and would die without attaining the Blessed Realm. This was best summed up by the scholar, William Ready: “But man falters often, so that there is apprehension ever in his tale.”

While Tolkien’s description of the Blessed Realm is often a little nebulous, it is clearly evident that he intended it to be a portion of heavenly Menel. Whether the Blessed Realm is some sort of afterlife, purgatory or indeed Heaven itself is purely a game of personal interpretation. Still, it is quite apparent that these Undying Lands are a paradise of sorts, which Men can attain by dying, and only through the grace of Ilúvatar. There, it is quite reasonable to view the Blessed Realm as the City of God, which the good Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis first laid down for us.

Tolkien and Thomas Aquinas

Without using blatantly theological terminology, Tolkien’s ideas are deeply rooted in theology, nonetheless. His beliefs are, to quote Paul H Kocher, “best understood when viewed in the context of the natural theology of Thomas Aquinas, whom it is reasonable to suppose that Tolkien, as a medievalist and a Catholic, knows well.” Some of Aquinas’ less specifically Christian propositions about the nature of evil correspond well with what Tolkien expresses or implies in layman’s terms. And while Tolkien did not quite adhere to the Manichaean philosophy of Dualism, The Silmarillion does indeed deal with the opposing forces of Good and Evil.

The great symbol and force of evil in The Silmarillion is Morgoth, who was one of the Valar who chose to enter into the world. Like Lucifer, upon whom he is modeled, Morgoth was filled with pride and was of a jealous nature. Once favored by Ilúvatar, Morgoth chose to corrupt Arda, to claim it for his own. “In the powers and knowledge of all the other Valar he had a part, but he turned them to evil purposes and squandered his strength in violence and tyranny, for he coveted Arda and all that was in it.” But Morgoth’s betrayal of Menel and his corruption of Middle-earth was long foreseen by Ilúvatar, for that was a part of his Vision and the reason he set the Valar to be the guardians and the warriors of Arda; there was purpose even in the sins of Morgoth.

Tolkien and the Concept of Free Will

Not unlike Saint Augustine, Tolkien believed in free will. Thus, even the Valar were given the freedom to choose between good and evil, as can be witnessed by Morgoth’s actions. Throughout The Silmarillion Tolkien shows us that consciousness goes hand in hand with the power to work towards good or evil. “Every intelligent being is born with a will capable of free choice, and the exercise of it is the distinguishing mark of his individuality.” Tolkien also held that the natural processes are good, that anything created by Eru Ilúvatar, or God, is good, and anything that interferes with this is evil. Free will coexists with a providential order and promotes this order, not frustrates it. Man, indeed, has a choice: “If he wills it, he can relate to all that is good in nature and beyond.”

The irony of Tolkien’s evil is that it often does the good that good itself sometimes cannot do. Providence, therefore, not only permits evil to exist, but weaves it inextricably into its own purposes. In the short term it may even allow evil to triumph. “Philosophically, if the guiding hand is really to guide effectively, it must have power to control events, yet not so much as to take away from the people acting them out or their capacity for moral choice.” Eru could easily destroy Morgoth, just as God can destroy Satan, for these personifications of evil are not equal to the ideal of absolute good. Why, then, is evil allowed to exist?

This is the eternal question many of us ask. There are two simple answers to that question: 1) without evil there would be no choice between good and evil, and thus there would be no such thing as free will; 2) because Man allows evil to exist, whether within himself or in the world, and only Man can destroy evil and cast it out of his world. Both answers are, in essence, the purpose of Eru’s plan.

Tolkien and Contemporary Society

The effect Tolkien had on society first occurred in the 1960s, mainly on college campuses across the country. He touched upon a need in socially-enlightened students (and those who were not students, as well) to escape for a time from the many troubles of the post-World War II world, such as the Bay of Pigs, the Cuban Missile Crisis, JFK’s assassination, and the Vietnam War. Along with two other major literary works of the 1960s, namely Robert A Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land and Frank Herbert’s Dune, The Lord of the Rings soon became the banner around which the counter culture rallied.

The effect Tolkien had on society first occurred in the 1960s, mainly on college campuses across the country. He touched upon a need in socially-enlightened students (and those who were not students, as well) to escape for a time from the many troubles of the post-World War II world, such as the Bay of Pigs, the Cuban Missile Crisis, JFK’s assassination, and the Vietnam War. Along with two other major literary works of the 1960s, namely Robert A Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land and Frank Herbert’s Dune, The Lord of the Rings soon became the banner around which the counter culture rallied.

Clearly there was much in Tolkien’s writing that appealed to the growing awareness of America’s youth of that time: the Baby Boomers. “It’s implied emphasis on the protection of natural scenery against the ravages of an industrial society harmonized with the growing ecological movement,” wrote Humphrey Carpenter. Frodo Lives! Gandalf for president! and Come to Middle-earth! became popular slogans on psychedelic buttons, posters and T-shirts. Carpenter also noted that: “At festivities in Saigon, a Vietnamese dancer was seen bearing the lidless eyes of Sauron on his shield, and in North Borneo a Frodo Society was formed.”

All across America local clubs of Tolkien-infatuated readers, loosely confederated as The Tolkien Society, spread like wildfire, while a deluge of amateur magazines swamped the United States Post Offices. Musicians wrote songs based on Tolkien’s works, and since the 1960s numerous books on Tolkien’s life and works have been written, and now internet websites by the score are dedicated to all things Tolkien. Fan-fiction and role-playing games based on Tolkien’s work became wildly popular. There have been major motion pictures made of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, and a television series based on The Silmarillion and the early history of Middle-earth is soon, as of this writing, to premier. In 2019, there was even a film based on Tolkien’s life, simply titled, Tolkien.

Tolkien first became a counter-culture hero, and then his popularity soon made him a huge, international celebrity. He was and still is a major influence and the inspiration in the ever-growing genre of epic fantasy. His legacy is solidly established and will no doubt still be around for many generations to come. As often as he is imitated, Tolkien can never be equaled nor duplicated, for he was “the fairest of all the Children of Ilúvatar that was or ever shall be.”

Prior Talking Tolkien entries:

Talking Tolkien – A New series at Black Gate!

Joe Bonadonna – Religious Themes in The Lord of the Rings

Ruth de Jauregui – The Architects of Modern Fantasy, Tolkien and Norton

Fletcher Vredenburgh – Of Such a Sort Should a Man Be – Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary

Anglachel – Tolkien’s Evil Magic Sword

David Ian – A Magical Tolkien Celebration

Gabe Dybing – Tolkien and Middle Earth Role Playing (MERP)

James McGlothlin -A Tolkienian Defense of Monsters

Thomas Parker – The Rankin-Bass Hobbit

Rich Horton – The Tolkien Reader

Joe Bonadonna is the author of the heroic fantasies Mad Shadows—Book One: The Weird Tales of Dorgo the Dowser (winner of the 2017 Golden Book Readers’ Choice Award for Fantasy); Mad Shadows—Book Two: The Order of the Serpent; Mad Shadows—Book Three: The Heroes of Echo Gate; the space opera Three Against The Stars and its sequel, the sword and planet space adventure, The MechMen of Canis-9; and the sword & sorcery pirate novel, Waters of Darkness, in collaboration with David C. Smith. With co-writer Erika M Szabo, he penned Three Ghosts in a Black Pumpkin (winner of the 2017 Golden Books Judge’s Choice Award for Children’s Fantasy), and its sequel, The Power of the Sapphire Wand.

He also has stories appearing in: Azieran: Artifacts and Relics; Savage Realms Monthly (March 2022); Griots 2: Sisters of the Spear; Heroika I: Dragon Eaters; Poets in Hell; Doctors in Hell; Pirates in Hell; Lovers in Hell; Mystics in Hell; Liars in Hell; Sinbad: The New Voyages, Volume 4; Unbreakable Ink; Poetry for Peace; the shared-world anthology Sha’Daa: Toys, in collaboration with author Shebat Legion; and with David C. Smith for the shared-universe anthology, The Lost Empire of Sol.

In addition to his fiction, Joe has written numerous articles, book reviews and author interviews for Black Gate online magazine.

Visit Joe’s Amazon Author’s page. His Facebook author’s page is called Bonadonna’s Bookshelf

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE DEFINITIVE guide to Conan. He also organized 2024’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, ans XXXIII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

Great essay.

It is odd that there is no reference to religion on Middle-Earth given Tolkien’s Catholic beliefs.