Talking Tolkien: On The Tolkien Reader – by Rich Horton

It’s another of my Black Gate cohorts this week for Talking Tolkien. Rich is one of the science fiction cornerstones at the Black Gate World Headquarters, but he’s been a Tolkien fan since the seventies. He’s gonna talk about a book I never added to my shelves. Before the explosion of books like The History of Middle Earth Series, and Children of Hurin, and his Beowulf, there weren’t a lot of ‘other’ Tolkien books out there besides the main five.

It’s another of my Black Gate cohorts this week for Talking Tolkien. Rich is one of the science fiction cornerstones at the Black Gate World Headquarters, but he’s been a Tolkien fan since the seventies. He’s gonna talk about a book I never added to my shelves. Before the explosion of books like The History of Middle Earth Series, and Children of Hurin, and his Beowulf, there weren’t a lot of ‘other’ Tolkien books out there besides the main five.

But even before The Silmarillion finally saw print, there was The Tolkien Reader.

______________________

The Tolkien Reader was first published in 1966 by Ballantine Books in the US; in response to the greatly expanding popularity of The Lord of the Rings, driven by the paperback editions from Ballantine (and the pirated edition from Ace.) This was an attempt to bring a varied sampling of his work to readers hungry for more. I read it myself in the early ’70s, after I read The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. As an introduction it reprints a piece Peter Beagle did for Holiday (perhaps at the instigation of Alfred Bester?) called “Tolkien’s Magic Ring”, which primarily discusses the Middle-Earth books.

It’s a good and varied collection throughout, and really does the job of showing a different side to Tolkien (though not THAT different!) from that seen in The Lord of the Rings. I’ll be looking at each of the sections separately, and slightly out of order, in that I think the best part by far is Tree and Leaf, which comes second in the book.

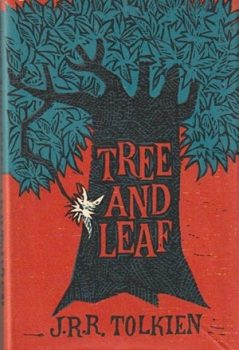

1. Tree and Leaf

On Fairy-Stories

The heart, or the engine (how Tolkien might have hated that metaphor), or the genius of The Tolkien Reader is this section. It consists of a long essay, “On Fairy Stories”, and a short story (or novelette), “Leaf by Niggle”. I think the essay is brilliant — if at times brilliant for the way it makes you dispute it; and the story is lovely, Tolkien’s best non-Middle Earth fiction — I might even argue his best fiction outside of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

In a brief introduction, presumably written for Tree and Leaf, a slim volume containing these two works, published in 1964, Tolkien says the pieces are paired because they were composed at about the same time (1938-1939) and because both used the metaphor of “Tree and Leaf”. “On Fairy-Stories” was first presented, in shorter form, as an Andrew Lang Lecture delivered at St. Andrews University in 1938. “Leaf by Niggle” first appeared in the Dublin Review for January 1945 (though Tolkien erroneously claims 1947.) In 1947 “On Fairy-Stories” appeared in a book called Essays Presented to Charles Williams, a book written as a memorial to Williams, who had died in 1945. (Williams of course was another of the Inklings, probably the third best known (as a writer, anyway) after Tolkien and C. S. Lewis.) Edward James told me at the World Fantasy Convention in New Orleans in 2022 that a further expanded version of “On Fairy-Stories” was published in 2008. Alas, I have not seen that yet!

Tolkien tells us he intends to answer three questions: “What are fairy-stories? What is their origin? What is the use of them?” As to the first question, much of his effort is spent contradicting familiar answers. He rails first against the idea that fairies are “diminutive” — he finds the fashion (then more prominent than now) for stories of tiny fairies, who could hide in a flower, for example, to be tiresome, and he quotes Andrew Lang: “They always begin with a little boy or girl who goes out and meets the fairies of polyanthuses and gardenias and apple-blossoms … These fairies try to be funny and fail; or they try to preach and succeed.”

He goes on to argue that fairy-stories are not usually about fairies, but about “men in the Perilous Realm or upon its shadowy marches.” For him, then, “A “fairy-story” is one which touches on or uses Faërie [that is, the land of Faërie], whatever its main purpose may be”. He explicitly excludes traveller’s tales (like Gulliver’s Travels), and Beast Fables, such as “The Monkey’s Heart” or “Reynard the Fox.” Most importantly, he argues that no fairy story can be explained as being just a dream. For, he writes, “It is essential to a genuine fairy-story … that it be presented as “true”.”

In considering the origin of fairy-stories, Tolkien first dismisses (to some extent) the effort many researchers (then and now) make to trace similarities and connections between different fairy-stories, or connections to old folk tales. Even when he acknowledges a real connection, he argues that “the coloring, the atmosphere, the unclassifiable individual details of a story” are what really counts. And so — while not denying the interest in unraveling “the intricately knotted and ramified history on the branches of the Tree of Tales”, comparing it to the discipline of philology, of which, he winkingly notes “I know some small pieces”. Tolkien of course agrees that fairy-tales have very ancient roots, and seem to be universal, and he notes three means by which they arise — independent invention, inheritance from an older tale, or diffusion from a different place. And, not surprising, it is invention that he considers most important.

And here it introduces one of his critical ideas — that fairy-stories make Man a “sub-creator”. That is, Faërie is not simply a symbolic representation of nature, nor are its inhabitants personifications of human traits. They are a new creation. Which is not to deny that they are still connected to ideas about nature or people. He argues that fairy stories have three faces: the Mystical (facing the supernatural), the Magical (facing nature), and the Mirror (looking with scorn and pity back at Man.) And for Tolkien, the Magical is the essential face.

Tolkien spends some time discussing potential real-world origins of fairy-stories — turning something that happened to a real person into a story. For Tolkien, it seems, such connections — real or not — are not the key elements of the story — the story is important in itself. And, indeed, Tolkien argues that the unexplainable, truly mysterious, parts of a fairy-story — and, too, the way these unfamiliar things can evoke deep time — are central to how they work.

Tolkien spends some time discussing potential real-world origins of fairy-stories — turning something that happened to a real person into a story. For Tolkien, it seems, such connections — real or not — are not the key elements of the story — the story is important in itself. And, indeed, Tolkien argues that the unexplainable, truly mysterious, parts of a fairy-story — and, too, the way these unfamiliar things can evoke deep time — are central to how they work.

Tolkien goes on to consider the notion that fairy-stories are primarily for children. He denies from his own experience that children are necessarily more attracted to fairy-stories than adults; and he avers that the association of fairy-stories with literature for children is a recent development. He is particularly critical of the habit of writing down to children (my words, not his) — “the old stories are mollified or bowdlerized” and new stories too often descend to “patronizing” or even “sniggering”. He goes on to say that the value of fairy-stories is if anything more needed by adults than children. While he acknowledges that the primary value is simply literary — the same value of any good writing — fairy-stories provide, “in a particular degree or mode” four specific things: Fantasy, Recovery, Escape, and Consolation, and he suggests that adults have a greater need for all of these than children.

The last two sections of the article (save the epilogue) consider these four things. Tolkien decides to use Fantasy to describe, in essence, the subcreative art of making objects of the imagination have the inner consistency of reality, yet retain a certain quality of strangeness. There’s a bit of vagueness here, but perhaps that is OK. I think he’s on to something, something hard to describe. At one limit, he is almost talking about world-building — but world-building at its most routine, I think, loses that quality of “strangeness”.

Tolkien suggests too that in this meaning, Fantasy is best restricted to the word — he deprecates the attempts of both visual art and drama to achieve true Fantasy. I can see what he’s getting at here — both are perhaps too concrete to truly sustain an inner consistency, and retain strangeness. (Though perhaps he understates the ability of artists and theater folks to transcend those limitations!) Tolkien also defines the elvish craft of making humans believe they are in a Secondary World — he rejects the words Magic and Art and suggests Enchantment, and then that when humans write (create) Fantasy they are aspiring to the elvish art of Enchantment. This seems true to me, even if I would suggest that some literary art not intending to be Fantasy also aspires to Enchantment.

By Recovery Tolkien means “regaining of a clear view” — that is, I think, relearning to see real things freshly, as if never seen before, and so to come closer to truly understanding them. In discussing Escape it is clear Tolkien is in part reacting to the complaints of so many critics that Fantasy is “escapist literature”, and he says “I do not accept the tone of scorn or pity” these critics use. For Tolkien, Fantasy IS a way to “escape” what “the misusers are fond of calling Real Life”. He says they are mistaking “the Escape of the Prisoner for the Flight of the Deserter” (and, indeed, he comes close to Godwinization by suggesting that this Escape is necessary for one living in “the misery of the Fuhrer’s … Reich”.)

Here we see Tolkien’s disgust, not just for Hitler but for much of the modern world, for industrialization in general — thus, for him, Escape, in Fantasy, to a world without “electric street-lamps” or “mass-production robot factories” is a good thing. (As John Kessel suggested to me, Tolkien’s attitude here is profoundly reactionary, and it is one of the instances where I must disagree with him. There is great beauty and great good that comes from the “modern” — electric street-lamps included! There is also of course ugliness and meanness and oppression — but so too did those exist in the bucolic past.) But Tolkien also acknowledges that this sort of Escape is a special case, and he adds more sensibly (to me) “There are other things more grim and terrible…. There are hunger, thirst, poverty, pain, sorrow, injustice, death.” Tolkien does not mean that Fantasy should not have those things, nor that the reader should forget that those things exist — but that to exist, in a sub-creation, without some or all such things is not an unworthy desire.

And, of course, in Escaping such sad things, there is Consolation. For Tolkien, this is not just the Consolation of escape from poverty or hunger or even death — but also, and most importantly, the Consolation of the Happy Ending. Here I will quote him at greater length: “Almost I would venture to assert that all complete fairy-stories must have it. At least I would say that Tragedy is the true form of Drama; its highest function; but the opposite is true of Fairy-Story. Since we do not appear to have a word that expresses this opposite — I will call it Eucatastrophe. The eucatastrophic tale is the true form of fairy-tale, and its highest function.”

This is in a way the very heart of this famous essay. It is not something I am convinced entirely by — I think Comedy as valuable as Tragedy in Drama, and likewise I think a true Fairy-story may instead have a Sad ending — a dyscatastrophe. But I am convinced by Tolkien’s defense of the power of the Happy Ending, another element of Story that some critics disparage. As Tolkien writes “it does not deny the existence of … sorrow and failure … it denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat … giving a glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.”

This is in a way the very heart of this famous essay. It is not something I am convinced entirely by — I think Comedy as valuable as Tragedy in Drama, and likewise I think a true Fairy-story may instead have a Sad ending — a dyscatastrophe. But I am convinced by Tolkien’s defense of the power of the Happy Ending, another element of Story that some critics disparage. As Tolkien writes “it does not deny the existence of … sorrow and failure … it denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat … giving a glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.”

This is Tolkien the Christian writing, and it is a religious statement I think. And in the Epilogue Tolkien makes this more explicit: discussing the sub-creation involved in writing Fantasy as a form of truth echoing the truth of Creation; and of redemption. “The Evangelium has not abrogated legends; it has hallowed them, especially the happy ending.”

I find this essay profound and powerful, beautifully written, quite successful on its terms. It is not the last word on Fairy-stories — it can and should be argued with, certainly, but what Tolkien says is intriguing and useful. (He also successfully invented a word in Eucatastrophe.) It is also endlessly quotable (the idea that Tolkien was not a good writer of prose is absurd!) and I will close by sprinkling in a few more quotes.

“The realm of fairy-story is wide and deep and high and filled with many things: all manner of beasts and birds are found here, shoreless seas and stars uncounted; beauty that is an enchantment, and an ever-present peril; both joy and sorrow as sharp as swords.”

“The road to fairyland is not the road to Heaven; nor even to Hell, I believe, though some have held that it may lead there indirectly by the Devil’s tithe.”

“Is there any cause for comment, if an adult reads [fairy-stories] for himself? Reads them as tales, that is, not studies them as curios. Adults are allowed to collect and study anything, even old theater programmes or paper bags.”

“Fantasy remains a human right: we make in our measure and in our derivative mode, because we are made: and not only made, but made in the image and likeness of a Maker.”

“All tales may come true; and yet, at the last, redeemed, they may be as like and unlike the forms that we give them as Man, finally redeemed, will be like and unlike the fallen that we know.”

Leaf by Niggle

In the introduction to Tree and Leaf, Tolkien writes of “On Fairy-Stories” and “Leaf by Niggle”: “Though one is an essay, and the other a story, they are related: by the symbols of Tree and Leaf, and by both touching in different ways on what is called in the essay ‘sub-creation.'”

“Leaf by Niggle” begins “There was once a little man called Niggle, who had a long journey to make. He did not want to go, indeed the whole idea was distasteful to him; but he could not get out of it.” Niggle was a mostly unsuccessful painter, and a vaguely kind man who (a bit half-heartedly) would do odd jobs for his lame neighbor Mr. Parish. He is working on an ambitious painting — as with many of his paintings, perhaps “too large and ambitious for his skill.” For “he was the sort of painter who can paint leaves better than trees.” And this painting began with a leaf, and became a tree, and the tree grew …

“Leaf by Niggle” begins “There was once a little man called Niggle, who had a long journey to make. He did not want to go, indeed the whole idea was distasteful to him; but he could not get out of it.” Niggle was a mostly unsuccessful painter, and a vaguely kind man who (a bit half-heartedly) would do odd jobs for his lame neighbor Mr. Parish. He is working on an ambitious painting — as with many of his paintings, perhaps “too large and ambitious for his skill.” For “he was the sort of painter who can paint leaves better than trees.” And this painting began with a leaf, and became a tree, and the tree grew …

As Niggle’s journey approaches, there is less and less time for him to work on his painting, and more and more interruptions — Mr. Parish’s wife falls sick and Niggle must go fetch her a doctor, then he too falls sick; and then an Inspector comes and commandeers his canvas to help make repairs to Mr. Parish’s house … and suddenly his Driver comes, and he must leave on his journey.

Niggle had not had time to pack, and on arriving at his destination (whatever that might be) is instead taken off to the Workhouse Infirmary, and set to work doing carpentry, then digging, and then resting — and then, curiously, in the dark he hears Voices discussing his case — arguing his merits — his reluctance to help people set against the fact that he did help them, his neglect of the Law set against his humility, his complaining set against his lack of expectation of reward. And before long Niggle is released to “the next stage”. The next stage proves to be a journey to the country, and in fact to his Tree — now real, and a forest with it. After a time he asks for Mr. Parish to join him; and they work together for a time, improving the land around the forest, planting a garden, drinking from the Spring in the forest.

And the time comes when Niggle must move on, while Parish must wait for his wife — and some of Tolkien’s most moving writing, leading to this great paragraph: “He was going to learn about sheep, and the high pasturages, and look at a wider sky; and walk ever farther and farther towards the Mountains, always uphill. Beyond that I cannot guess what became of him. Even little Niggle in his old home could glimpse the Mountains far away, and they got into the borders of his picture; but what they are really like, and what lies beyond them, only those can say who have climbed them.”

There follows a brief postscript, two men talking about Niggle, one disparaging his usefulness, the other praising the odd corner of a painting he found, torn from the canvas used to repair Parish’s house — preserved in a museum for a time as one little painting called “Leaf: by Niggle”.

This is a beautiful beautiful story. It seems to be — I hesitate to insist on a fixed meaning, but it seems to be — a symbolic portrayal of a man — two men — growing up, learning to be better men, moving towards what must be God, and Heaven. Or it is about — also about — sub-creation: Niggle’s painting becomes Real, Parish’s garden becomes Real, becomes a place where people live. So — Art is Real, and so is Work, if done with the right spirit, if done by humans who have been given a piece of God’s ability to Create. But read the story yourself, and decide what it means for you!

In “On Fairy-Stories” Tolkien wrote of the Tree of Tales, and the leaves on that Tree must be individual stories, and writers of stories are Creators — subcreators — of something that is, in important ways, Real. And “Leaf by Niggle” is one such Leaf on the Tree of Tales, just as “Leaf: by Niggle” was a perfect Leaf Created by the man Niggle.

2. The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth: Beorhthelm’s Son

This was first published in 1953 (the year before The Lord of the Rings began appearing) in the scholarly journal Essays and Studies by Members of the English Association. It consists of a poem or verse play inspired by a long Old English verse fragment called “The Battle of Maldon”; and two short essays by Tolkien, one preceding the poem, the second following. The first, “Beorhthnoth’s Death”, discusses the historical context of the poem — an actual battle fought in 991; the second, “Ofermod”, is a discussion of a couple of lines from “The Battle of Maldon”, in which a subordinate criticizes Beorhtnoth’s actions — as, in essence, too courageous, too chivalrous. (He had allowed the invading “Danes” free crossing of a difficult bridge, in order that there would be a fair fight, instead of defending the bridge. The result was not just Beorhtnoth’s death, but that of most of his fellows.) Tolkien argues, in essence, that Beorhtnoth was too proud, and allowed his overweening belief in his courage to prevent him from doing his true duty: saving his people from invasion.

This was first published in 1953 (the year before The Lord of the Rings began appearing) in the scholarly journal Essays and Studies by Members of the English Association. It consists of a poem or verse play inspired by a long Old English verse fragment called “The Battle of Maldon”; and two short essays by Tolkien, one preceding the poem, the second following. The first, “Beorhthnoth’s Death”, discusses the historical context of the poem — an actual battle fought in 991; the second, “Ofermod”, is a discussion of a couple of lines from “The Battle of Maldon”, in which a subordinate criticizes Beorhtnoth’s actions — as, in essence, too courageous, too chivalrous. (He had allowed the invading “Danes” free crossing of a difficult bridge, in order that there would be a fair fight, instead of defending the bridge. The result was not just Beorhtnoth’s death, but that of most of his fellows.) Tolkien argues, in essence, that Beorhtnoth was too proud, and allowed his overweening belief in his courage to prevent him from doing his true duty: saving his people from invasion.

The central poem, then, is a dialogue between two men working on retrieving the dead bodies from the battlefield, including that of Beorhtnoth. One of them kills a man sneaking onto the field (presumably trying to steal from the dead.) The two discuss Beorhtnoth’s actions — one praising him for his courage and chivalry, the other criticizing him.

It’s decent work, I think, and a reasonable capturing of Old English poetic style, but not brilliant. (I love some Old English poetry, such as “The Wanderer”.) The moral discussion at the heart of it is worthwhile.

3. Farmer Giles of Ham

This is the part of The Tolkien Reader I most enjoyed when I first found the book at age 12 or so. That was because it is comic/satirical in intent, and also perhaps because it’s illustrated (by Pauline Baynes.)

The full title of “Farmer Giles of Ham” is given as “The Rise and Wonderful Adventures of Farmer Giles, Lord of Tame, Count of Worminghall, and King of the Little Kingdom”. It purports to be set some time after King Coel, and before Arthur, somewhere in the valley of the Thames. (Later Tolkien jestingly suggests that the name “Thames” is derived from Ham.) Ægidius de Hammo — or Ægidius Ahenobarbus Julius Agricola de Hammo — is a farmer in the village of Ham, but “folk were fewer, so that most men were distinguished”, hence the long Latin name. But for the rest of the narrative he is mostly called, in the Vulgar, Farmer Giles of Ham.

Giles has a dog named Garm, who, like most dogs in those days, can speak in the vulgar tongues. Their village is being harassed by a giant — more or less by accident. And Garm and Giles, also more or less by accident, manage to chase the giant away. And as a result Giles is considered a hero, and the King commends him — and even gives him a sword. Giles is happy enough about this.

The catch comes when a dragon — lured by the giant’s careless words — begins to ravage the Little Kingdom. People demand action, and as it comes closer to Ham, the people begin to look to Giles for protection. After all, he is the knight who saved them from the giant, right? In vain does Ham protest that he has not been formally dubbed a knight …

The catch comes when a dragon — lured by the giant’s careless words — begins to ravage the Little Kingdom. People demand action, and as it comes closer to Ham, the people begin to look to Giles for protection. After all, he is the knight who saved them from the giant, right? In vain does Ham protest that he has not been formally dubbed a knight …

Eventually Giles is forced to go and face the dragon. And all seems to be lost — except that his sword, called Tailbiter, turns out to be magic — and also famous. It leaps at the dragon on its own and the dragon recognizes it — and is afraid. The upshot is that the dragon decides a wiser course than fighting is to cut a deal with Giles — and Giles too certainly thinks that’s better than fighting. From there we follow the results of the deal Giles makes, and his need to hold the dragon to its terms, and also to make the King live up to certain promises — and Giles, as the full title revealed to us already, does well enough for himself. (As does the dragon, all things considered.)

This is amusing stuff, really. Perhaps the more so the first time you encounter it. It’s a story worth reading — but it’s minor work next to “Leaf by Niggle”, and certainly next to The Lord of the Rings.

4. The Adventures of Tom Bombadil

This is a selection of 16 poems, all supposedly from The Red Book of Westmarch. They are presented as poems hobbits enjoyed. Only two feature Tom Bombadil. A couple of the poems are “attributed” to Bilbo, and a couple to Sam Gamgee — one is “associated” with Frodo. This collection was assembled by Tolkien at the suggestion of his aunt, for publication in 1962, in a slim book also illustrated by the great Pauline Baynes. The poems actually were composed mostly in the ’20s and ’30s, with one dating to 1915, and only one (“Bombadil Goes Boating”) written for the book. A few appeared in The Lord of the Rings.

The poems are all metered and rhyming, the meter often a bit bouncy. Certainly they are old-fashioned, and some are a bit twee. There is a distinct range of mood and style, with some humorous, and one at least effectively horrific (“The Mewlips”), and some atmospheric and moody. The best, to my ear, is the last, “The Last Ship”, about a human woman watching the last ship leaving for Elvenhome. It’s a lovely, sad piece.

Prior Talking Tolkien entries:

Talking Tolkien – A New series at Black Gate!

Joe Bonadonna – Religious Themes in The Lord of the Rings

Ruth de Jauregui – The Architects of Modern Fantasy, Tolkien and Norton

Fletcher Vredenburgh – Of Such a Sort Should a Man Be – Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary

Anglachel – Tolkien’s Evil Magic Sword

David Ian – A Magical Tolkien Celebration

Gabe Dybing – Tolkien and Middle Earth Role Playing (MERP)

James McGlothlin -A Tolkienian Defense of Monsters

Thomas Parker – The Rankin-Bass Hobbit

Rich Horton is a software engineer for a large aerospace company in St Louis. He wrote a column on short fiction for Locus Magazine for 20 years and has edited a series of Best of the Year anthologies since 2006. He writes about SF history, old magazines, Ace Doubles, old bestsellers, Victorian literature, and even reviews recent SF/F novels at his blog Strange at Ecbatan and at Black Gate.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE DEFINITIVE guide to Conan. He also organized 2024’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, ans XXXIII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

Leaf by Niggle first appeared in The Dublin Review? I didn’t know that. We had stacks of The Dublin Review in my parents’ attic (my grandad was an author of sorts and had stuff in it from time to time). It was the Irish literary magazine of its day.

There’s a lot to digest here, Rich. I think Tolkien is right to say that any fantasy needs an element of strangeness to really work. I think this is the essence of the genre, but that works of fantasy sometimes end up being precisely what the word means in the conventional sense, too; stories in which heroic people do heroic things and always end up defeating evil – ie, that the accusations of escapism aren’t unjustified.

In Ireland the small size of the Sidhe correlates with how they were subjugated by the Gaels and went into hiding underground. So their diminished size is a reflection of their diminished relevance and the fact that they’re a defeated race.

And yeah, Tolkien really had a thing about trees!* I watched The Father a while back. I’d heartily recommend it. I think it functions just as well as a horror movie as a study of Alzheimers. There’s a particularly poignant scene at the end in which Hopkins’ character weeps and says he’s losing all his leaves, thanks to wind, rain etc. I thought it was a great analogy. Then I came across a letter from Tolkien to his daughter shortly after C.S. Lewis’s death. ‘So far I have felt the normal feelings of a man of my age—like an old tree that is losing all its leaves one by one: this feels like an axe-blow near the roots.’

*Leaf by Niggle seems to reflect a certain trend at the time for stories that were religious allegories, some by the most unlikely people (E. M. Forester springs to mind).

Thanks!

Yes, E. M. Forster wrote some quite excellent allegoryish stories. “The Other Side of the Hedge” definitely has points of correspondence with “Leaf by Niggle”. “The Celestial Omnibus” is another example. (I reviewed his complete short fiction here: https://rrhorton.blogspot.com/2017/01/old-bestseller-collected-tales-of-e-m.html)

Great review, Rich. I’m always curious about authors who stop early on in life – e.g. Dashiell Hammett. The story about the faun stuck in my mind (I wondered at the time if it had been the inspiration for Mr Tumnus), also a story about two friends, one who goes to Heaven and the other who goes to Hell (or purgatory). I think you’re right that Forster was still finding his feet as a writer; I get the impression the novels are more fully realised, although I haven’t read any of them either!

Great and thorough review. This book is packed with valuable gems. “On Fairy-Stories” is deep and profound. Anyone interested in fantasy should read it.

My monthly sf/f reading group tackled the newer version, Tales from the Perilous Realm, which adds in his children’s romp “Roverandom” and his other noted fantasy short story, “Smith of Wooton Major”. We tended to be a bit contrary in our likes for the material (like preferring the dragon Chrysophylax Dives over Farmer Giles himself), but still impressed by the character growth and sense of artistic creation in “Leaf by Niggle” (though I would have guessed it a C. S. Lewis piece if found unattributed). And Prof. Tolkien’s critique of non-literary forms of Faerie had us wondering just what he would have said about the Peter Jackson films.

Nice to see you at Readercon, too, Mr. Horton, though I missed your bodice-ripping talk due to lingering over dinner. Sorry!

That bodice-ripping panel ended up to be just me! (A coujple of panelists had to cancel in advance, and one got sick and had to go home.) So I need to thank the audience members, who did a great job of suggesting various pet peeves, etc.

Good going with the audience participation! One of my favorite con panels was on ‘snowball Earth’ at World Fantasy Con (2007, Saratoga Springs), where neither panelist arrived, but the audience had enough informed folks that a whole new panel was drafted and a very informative talk followed.

Also, I suspect Tolkien would have rather disliked Jackson’s films, and never would have allowed the abomination that is Jackson’s Hobbit trilogy. For myself, I like Jackscon’s LOTR, despite some serious reservations; and I detested the first Hobbit film and never watched the other two.

Excellent post, Mr. Horton. Thank you.

I have all those books, but earlier editions; wish you could have posted those images here.

[…] WHEN THE WORLD DISCOVERED TOLKIEN WROTE OTHER THINGS. “Talking Tolkien: On The Tolkien Reader” by Rich Horton at Black […]