Talking Tolkien: Does Size Matter? The Rankin-Bass Hobbit by Thomas Parker

Fellow Black Gater Thomas Parker and I share quite a few interests – but within those interests we tend to vary wildly. I enjoy chatting with him. I conned him into writing a…I mean, he graciously agreed to do a Horace McCoy piece for A (Black) Gat in the Hand, and I’ve been after him to shore up my Black Gate views by doing a guest piece for me. And man, do I LOVE this one on the Rankin-Bass classic, The Hobbit. It was worth the past four years of badgering him. Read on!

Fellow Black Gater Thomas Parker and I share quite a few interests – but within those interests we tend to vary wildly. I enjoy chatting with him. I conned him into writing a…I mean, he graciously agreed to do a Horace McCoy piece for A (Black) Gat in the Hand, and I’ve been after him to shore up my Black Gate views by doing a guest piece for me. And man, do I LOVE this one on the Rankin-Bass classic, The Hobbit. It was worth the past four years of badgering him. Read on!

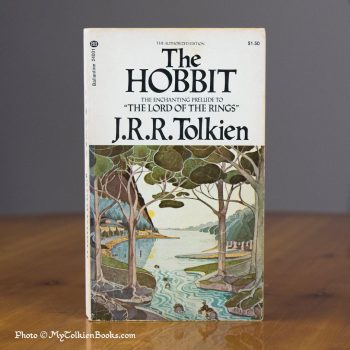

Let me begin with a statement that is impossible to prove but that almost no one would dispute: J.R.R Tolkien’s 1937 children’s fantasy The Hobbit is one of the most beloved books in the world, and because it serves (according to the cover of my old Ballantine paperback) as the “enchanting prelude to the Lord of the Rings” it is also one of the most influential books of the last century, all of which means that those who would presume to adapt the story for other media would be wise to tread warily.

Over the decades, there have been stage adaptations (including an operatic one), graphic novels, and many audio renderings. But when it comes to film adaptations, there are really only two versions to choose from, and they couldn’t be more different in scale, emphasis, and execution.

Most recently we have the triple-decker expansion offered by Peter Jackson — The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (2012), The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug (2013), and The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies (2014), three movies that together have a running time of almost eight hours and that were made with all the technical sophistication and immense resources that Mordor… er, a major Hollywood studio can offer. The trilogy had combined budgets of six hundred and sixty-five million dollars, and during their initial theatrical releases the films netted approximately three billion dollars (to say nothing of profits from home video and merchandising). As the Dark Lords of the boardroom can tell you, each zero in those immense grosses is a veritable Ring of Power in itself.

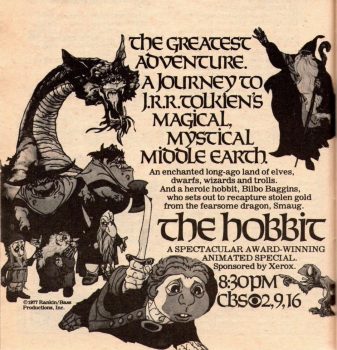

On the other side of the scale, you have The Hobbit, an animated film done for television by the Rankin-Bass studio, with a running time just short of eighty minutes and a budget of around three million dollars. How much the movie made for the manufacturers of Leggs pantyhose and Maytag dishwashers when it aired on the NBC network on November 27th, 1977 is impossible to determine at this late date, but I can say with some confidence that it sure wasn’t three billion dollars.

On the other side of the scale, you have The Hobbit, an animated film done for television by the Rankin-Bass studio, with a running time just short of eighty minutes and a budget of around three million dollars. How much the movie made for the manufacturers of Leggs pantyhose and Maytag dishwashers when it aired on the NBC network on November 27th, 1977 is impossible to determine at this late date, but I can say with some confidence that it sure wasn’t three billion dollars.

So, which version should the lover of Tolkien choose — the juggernaut or the flea? The triple-headed economic and technological behemoth that was a follow-up to the Oscar winning, much-beloved original Jackson trilogy, or the modest cartoon that has been described (by Tolkien scholar Douglas Anderson) as “execrable”? Glad you asked!

Rankin-Bass holds a special place in the hearts of baby boomers of a certain age, due to their stop-motion and traditionally animated Christmas specials Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, Santa Claus is Coming to Town, and Frosty the Snowman, and theatrical movies like Mad Monster Party and The Daydreamer. These and other Rankin-Bass productions set the pattern for the kind of dewy-eyed, musical whimsy that dominated the children’s programming of the 60’s and 70’s. The studio’s methods worked fine with Rudolph, Hermie, and Yukon Cornelius — how did it work with Bilbo and Gandalf?

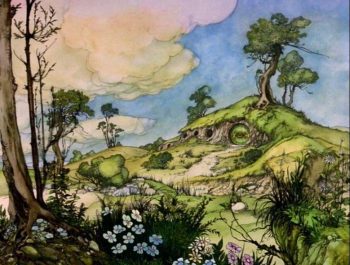

Visually, the Rankin-Bass film is decent enough for a half-century old television show. Like many R-B productions, the animation was done by the Japanese firm Topcraft (which eventually morphed into Studio Ghibli). The backgrounds are pleasing, having more of a Tim Kirk or Arthur Rackham flavor than more recent renderings of Middle-earth, while the characters, especially Bilbo look… well, Rankin-Bassish.

Visually, the Rankin-Bass film is decent enough for a half-century old television show. Like many R-B productions, the animation was done by the Japanese firm Topcraft (which eventually morphed into Studio Ghibli). The backgrounds are pleasing, having more of a Tim Kirk or Arthur Rackham flavor than more recent renderings of Middle-earth, while the characters, especially Bilbo look… well, Rankin-Bassish.

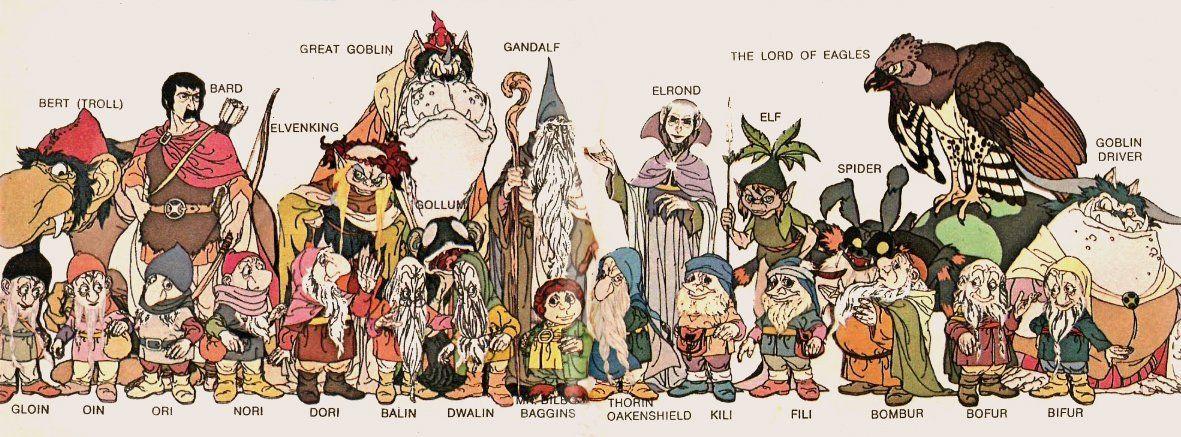

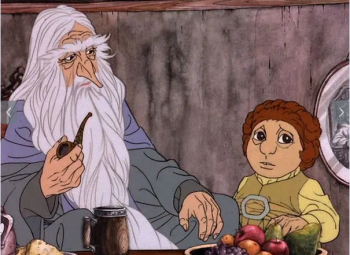

Bilbo is short and very round, with big eyes and slightly buck teeth; the effect is a bit like a stout, bipedal chipmunk, but as Mr. Baggins is the only hobbit we see, it doesn’t hurt much. Gandalf looks properly wizardly with a long, pointed nose, flowing white beard and blue robe, and the dwarves are dwarvish; they lean a little in the direction of the Disney characters of Snow White, but not far enough to fall over.

In some of the other characters, there are occasional odd choices. Tolkien describes the trolls simply: they are “very large persons” with “great heavy faces.” The Topcraft animators followed that and added their own embellishment — one of the trolls has a large set of tusks. Tolkien’s goblins are “big goblins” and “great, ugly-looking goblins” and Rankin-Bass gives us bulky creatures with greyish skin, horn-topped heads, wide mouths with sharp, upward-pointing teeth and slitted eyes like cats. The spiders of Mirkwood are properly arachnoid, hairy and dripping with venom.

The elves in the book are “tall”, “noble”, and “fair of face.” The animated Elrond matches this reasonably well, but again there is an eccentric addition — a sort of floating halo or crown of stars around his head, while the Elven-King and his wood-elves are visualized as almost a different species of creature than Elrond, perhaps because Elrond was only half-elven; the Elven-King and his minions have greyish-blue skin and emaciated-looking bodies that are almost gnarled and twisted like the trees of the forest in which they live.

Smaug, described by Tolkien as a “vast, red-golden dragon” is made by the animators vast and red-golden. He was probably the easiest character to do — everyone knows what a dragon looks like. Likewise, there are no surprises in the depiction of Smaug’s foes, Bard and the men of Lake-Town, who have the look of off-the-rack medieval townspeople. In reviewing the novel, I was reminded of how minimal Tolkien’s character descriptions usually are, which gave the Rankin-Bass team a lot of leeway. Aside from the wood-elves, the character where they depart the farthest from Tolkien’s description (or at least from the way most of us probably picture him) is Gollum.

Smaug, described by Tolkien as a “vast, red-golden dragon” is made by the animators vast and red-golden. He was probably the easiest character to do — everyone knows what a dragon looks like. Likewise, there are no surprises in the depiction of Smaug’s foes, Bard and the men of Lake-Town, who have the look of off-the-rack medieval townspeople. In reviewing the novel, I was reminded of how minimal Tolkien’s character descriptions usually are, which gave the Rankin-Bass team a lot of leeway. Aside from the wood-elves, the character where they depart the farthest from Tolkien’s description (or at least from the way most of us probably picture him) is Gollum.

Tolkien says that Gollum is “a small, slimy creature” with “two big round pale eyes in his thin face.” The Rankin-Bass Gollum is small of stature but not particularly thin; compared to the Peter Jackson version he’s quite plump, and taking their cue from his living on an island in an underground lake and paddling his boat with his feet, the animators give the creature an amphibious, almost frog-like look, replete with a wide, thick-lipped mouth and greenish skin.

The Hobbit’s voice cast is generally strong. The ubiquitous (he had an almost fifty-year career in movies and television) Orson Bean is Bilbo, and he does nicely by the character, sounding especially convincing when the hobbit has had it with the dwarves and longs for nothing more than to be back in his nice, cozy hobbit-hole. Thorin is lent the lemony tones of the veteran character actor Hans Conreid. He spends just as much time being put-out with Bilbo as Bilbo does being put-out with him, and in these moments Conreid sounds like someone who is being forced to smell something disgusting that’s being held directly under his nose and wants it taken away immediately. Western star Richard Boone does well with Smaug, though he is perhaps a little rougher-edged than is ideal for the devious worm, while the distinguished English actor Cyril Ritchard gives the pronouncements of Elrond a proper weight and dignity.

Then there is the film’s German contingent. The director (Laura, Anatomy of a Murder) and actor (he specialized in Nazis like his concentration camp commandant in Stalag 17) Otto Preminger plays the Elven-King as… well, rather like a highly ticked-off concentration camp commandant, which isn’t that far off from the novel’s Elven-King and his hard-nosed attitude toward these obstreperous dwarves. It must be said, though, that Preminger’s thick Prussian accent is somewhat disconcerting coming from an elf. To add to The Hobbit’s Teutonic flavor, Theodore Gottlieb (of Düsseldorf, no less) gives Gollum a voice that is like nothing so much as an amyl-nitrate sniffing Peter Lorre. (I know Lorre was Hungarian, but you get what I mean.) Coupled with the animators’ unique visualization, Gottlieb’s eccentric interpretation makes Gollum the film’s most striking and memorable character, and though this Gollum is not to everyone’s taste, I’ve always rather liked him.

The Hobbit’s outstanding voice performance, though, is John Huston’s Gandalf. The director of some of the greatest American movies (The Maltese Falcon, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, The African Queen) and occasional actor (his Noah Cross in Chinatown is among the most chilling of all screen villains), Huston was ideal for the wizard; his rich, distinctively weathered voice conveys all the wisdom, authority, and humor of the character. Indeed, if a live film instead of an animated one had been made at this time, there could have been no better choice for the role than John Huston; all who knew him regarded him as a bit of a sorcerer himself.

The Hobbit’s outstanding voice performance, though, is John Huston’s Gandalf. The director of some of the greatest American movies (The Maltese Falcon, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, The African Queen) and occasional actor (his Noah Cross in Chinatown is among the most chilling of all screen villains), Huston was ideal for the wizard; his rich, distinctively weathered voice conveys all the wisdom, authority, and humor of the character. Indeed, if a live film instead of an animated one had been made at this time, there could have been no better choice for the role than John Huston; all who knew him regarded him as a bit of a sorcerer himself.

Bill the Troll and Bombur are played by Paul Frees, a man who spent much of his life talking back and forth to himself in different voices which could all ultimately be identified, by trained and untrained ears alike, as belonging to Paul Frees. The ever-stalwart Jack DeLeon, Don Messick, and John Stephenson voice everyone else in the film (DeLeon did nine of the dwarves) which sometimes results in the aural equivalent of watching Fred Flintstone spend five minutes running past the same couch.

There are some hits and some misses in The Hobbit’s visuals and in its portrayal of the characters, but there are few utterly indefensible choices. More controversial is what it does with the story itself; it was Romeo Muller’s script that Douglas Anderson labeled execrable (though Muller won a Peabody Award for it, so someone must have liked it).

Where Jackson worked the bicycle pump until he had blown Tolkien’s tale up so big that it required three almost three-hour films to get there and back again, Muller had a mere seventy-eight minutes to work with. Where Jackson threw in kitchen sink after kitchen sink (do hobbit-holes even have kitchen sinks?), Muller had to cut and condense unsparingly to fit in the bare rudiments of the tale. Whole subplots disappear, some more significant than others.

The interlude with Beorn is dropped, many incidents in the long, wearisome journey through Mirkwood (the enchanted stream that puts Bombur to sleep, for instance) are cut, and most importantly, the Arkenstone and the fracas that ensues when Bilbo appropriates it are nowhere to be seen; the breach between Bilbo and Thorin results entirely from Bilbo’s council of compromise before the Battle of the Five Armies and not from his giving the stone to Thorin’s enemies to barter with, with the unfortunate effect of lessening Bilbo’s courage and moral stature.

The condensations and omissions made necessary by the short running time give the Rankin-Bass film a much quicker pace than that of Tolkien’s relaxed, leisurely narrative; even so, The Hobbit finds time for several songs, which is the area where many viewers are most critical of the movie. The lyrics are mostly close adaptations of the songs in the novel, which Tolkien apparently did not intend to be taken seriously. (“Then off they went into another song as ridiculous as the one I have written down in full.”)

The condensations and omissions made necessary by the short running time give the Rankin-Bass film a much quicker pace than that of Tolkien’s relaxed, leisurely narrative; even so, The Hobbit finds time for several songs, which is the area where many viewers are most critical of the movie. The lyrics are mostly close adaptations of the songs in the novel, which Tolkien apparently did not intend to be taken seriously. (“Then off they went into another song as ridiculous as the one I have written down in full.”)

These musical interludes may seem an abomination to those raised on Beyoncé and to those who find the light-hearted tunes injurious to the dignity of Tolkien, but in the novel, Bilbo and the elves (here more silly than staid) and the thick-headed dwarves are not dignified characters. If you demand full Lord of the Rings seriousness and decorum, you must retrofit them onto The Hobbit. (Tolkien of course did a bit of that himself when he revised his novel — especially the “Riddles in the Dark” chapter — in order to bring it more in line with his later work, but he didn’t revise enough to change the overall humorous tone of the book.)

Despite its lapses, however, the animated film gets many things right — Bilbo’s initial meeting with the dwarves, the comically grim encounter with the trolls, the tense riddle-game with Gollum, the battle with the spiders, and especially Bilbo’s moving reconciliation with the Dying Thorin, are all quite well done, and convey the book’s essential shape and flavor more than just adequately. I especially like the ending; instead of all the intrusive, forced linkages with the succeeding story that are shoehorned into the Jackson films, we see the ring gleaming in a glass display dome on Bilbo’s mantle, and hear the voice of Gandalf: “Oh, Bilbo Baggins, if only you understood that ring, as someday members of your family not yet born will, then you’d realize that this story is not yet ended, but only beginning!” It’s just enough and not too much (which might be a hobbit proverb), and it gives me a delightful shiver every time.

So, which of the available versions is “better?” The small or the large? The old or the new? The modest or the ambitious? The execrable or the acclaimed? (The Jackson movies have an average 7.7 IMDB rating. The R-B currently sits at 6.7.)

I loved Peter Jackson’s original Lord of the Rings films; I think Fellowship, Towers, and Return constitute a magnificent achievement and I will forever be grateful to have them, and I return to them frequently. While I didn’t agree with every directorial and screenwriting decision (and who would?), Jackson showed the greatest wisdom in knowing that special effects and cinematic tricks should serve the story rather than dominate it. What ultimately makes those first three films true to Tolkien is that in them, human (or hobbit) values predominate.

I loved Peter Jackson’s original Lord of the Rings films; I think Fellowship, Towers, and Return constitute a magnificent achievement and I will forever be grateful to have them, and I return to them frequently. While I didn’t agree with every directorial and screenwriting decision (and who would?), Jackson showed the greatest wisdom in knowing that special effects and cinematic tricks should serve the story rather than dominate it. What ultimately makes those first three films true to Tolkien is that in them, human (or hobbit) values predominate.

But as one of the Wise — Elrond, Celeborn, Gil-Galad… oh yeah, it was Kenny Rogers — once said, you’ve got to know when to hold ‘em, know when to fold ‘em, know when to walk away and know when to run, and much of the honor that Jackson and his team won for themselves with the first three movies was squandered with the second trilogy, which was transparently made (and made a trilogy) not for love, but for money.

Now I know that movies are made to generate profits, but in the first three LOTR films what you feel is the filmmakers’ passion for the material and sympathy for Tolkien’s vision. In the three Hobbit movies, however, the thing that shines through most clearly is the desire to cash in. To take a lovely, humble tale like The Hobbit and distort its shape, undermine its sensibility, and blow it up beyond all reason, solely in order to triple the ticket sales — well, it’s akin to what the Dark Lord did when he changed elves into orcs.

This may be why, taken together, An Unexpected Journey, The Desolation of Smaug, and The Battle of the Five Armies feel less like Tolkien than like a cross between a poorly refereed D&D game and a below-average episode of the A-Team; after almost nine hours of being battered by a thuddingly obvious soundtrack and bludgeoned by soulless CGI, at least one viewer staggered out of the theater feeling as if he had been sealed inside a galvanized garbage can and kicked down a rocky slope. In their eagerness to cram in every possible link with the succeeding trilogy, Jackson and his collaborators produced bloated, overstuffed, shapeless films that convey very little of The Hobbit’s gentle spirit. Poor Bilbo (the title character, after all) tends to get lost in the welter of characters who never appeared in his book and among frantic, video-game like action sequences that are as alien to Tolkien’s sensibility as a weekend in Las Vegas (though they do say that what happens in Bree stays in Bree.)

The contrast with the Rankin-Bass movie couldn’t be greater, and the animated film’s successes are all the more admirable because it must be admitted that the studio’s style was not ideally suited to Tolkien. Their Hobbit has many flaws, but if I must choose between Rankin-Bass’s modest, silly cartoon and Peter Jackson’s multi-billion dollar epic, I am forced to choose the modest, silly cartoon, flaws and all, perhaps because “modest, silly cartoon” comes closer to the humane spirit of Tolkien’s story than “multi-billion dollar epic”, which, to me at least, smacks more of the cold and merciless machinery of Barad-Dûr (or at least Isengard) than it does of the sweet breezes and carefree songs of the Shire.

Prior Talking Tolkien entries:

Talking Tolkien – A New series at Black Gate!

Joe Bonadonna – Religious Themes in The Lord of the Rings

Ruth de Jauregui – The Architects of Modern Fantasy, Tolkien and Norton

Fletcher Vredenburgh – Of Such a Sort Should a Man Be – Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary

Anglachel – Tolkien’s Evil Magic Sword

David Ian – A Magical Tolkien Celebration

Gabe Dybing – Tolkien and Middle Earth Role Playing (MERP)

James McGlothlin -A Tolkienian Defense of Monsters

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was Living Large: Bert I. Gordon 1922-2023

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE DEFINITIVE guide to Conan. He also organized 2024’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, ans XXXIII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

I will always have a soft spot for the cartoon because it was my first introduction to Tolkien. I just wish they’d release a cleaned-up and properly remastered HD version.

Even if the title song (The Greatest Adventure) does sound like Glenn Yarborough is singing through a box fan.

I’ve never seen anything but snippets of the cartoon, but I agree that John Huston was a great choice for Gandalf and would have been a great live-action Gandalf. And I’m sure you are right about the cartoon being better than the Jackson trilogy, because those were, oh, what’s the word, what is it? Oh yeah: “Execrable”.

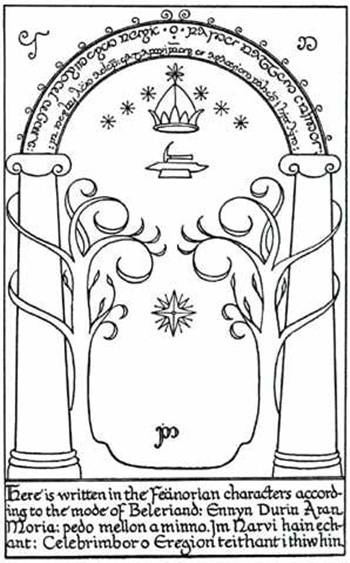

I thought the Rankin-Bass film was just OK, but I will go to the mat to defend Elrond’s star-halo. “Elrond” means “vault of stars”, but a hemisphere would have been visually ridiculous. The French word “rond” is right there with a powerful attractive force, in the back of every English-speaker’s mind, so a circle of stars was a perfect choice.

Nice to know what the animators’ rationale was – thanks! But I still think it looks funny.

Agree. Thank you, Mr. Parker.

There’s a huge divide between fans of the books that read them first and fans who enjoyed Jackson’s original LotR movies and then went back to the books.

Being one of the former, I disliked all (six) of his movies, but while I was at least appreciative that with the first three were not universal laughingstocks (easily done with hobbits!), the last three were so commercially crass that the producers of such trash should have suffered financial hardship and public humiliation. There is no justice. Consumers can be such indiscriminate pigs.

Returning to the original point of this post, the animated film did not rankled me or the many fans of the book I knew in the way that Jackson’s films did. I think part of the reason for that was the landscape for fantasy films of any sort in that era — it was an absolute desert. But even more so was that the Rankin-Bass animated shorts (I’m including the Return of the King now) did a wonderful job of capturing the tone of Tolkien’s novels far better than Jackson. The seemed to “get it” when it came to folklore and fairy tales with a heroic core. There is whimsy too in the Hobbit novel, and that translated in animation quite well.

In short, the visual excursions (gaffs?) and story condensation are forgivable because the tone of what (little) is there is so much more on key. All of the Jackson films felt to me like something foreign, Middle-Earth in name only. I am not convinced he ever really loved or “got” Tolkien. The essence is missing.

Now do Bakshi.

While writing this article, I didn’t even think about the Bakshi film; it didn’t occur to me until a day or two ago. I think it would be a hard rewatch. I saw it when it was released and remember leaving the theater baffled and disappointed. I know there were financial problems that kept Bakshi from doing what he originally envisioned, but I think a bigger problem was a misalignment of sensibilities, if you get what I mean. I might think differently if I saw the movie again – that original viewing was my only one and forty-five years is a loooong time!

I remember the R/B Hobbit fondly in part because it introduced me to the genre of fantasy. Up to that point, I had been reading youth mysteries (Hardy Boys and the like) but when I had to grab a book from the school library, I grabbed the Hobbit because I remembered the cartoon. And since then I haven’t looked back. While I have continued to read some mysteries (Agatha Christies mainly), my reading diet is now almost exclusively sci fi and fantasy. As for the cartoon and its fondness of song, I do recall a rousing version of “Where there’s a whip, there’s a way” being sung as part of a high school D&D session. Good times.

The mistake that the Peter Jackson Hobbit movies make is taking the cover blurb “prelude to the Lord of the Rings” too literally, using the same heroic tone and danger-laden atmosphere for Prof. Tolkien’s “enchanting” children’s tale. Which really does not work. So I plump for the Rankin-Bass version, too.

I go even a bit further and willingly say nice things about their next Tolkien adaptation, The Return of the King, where they do try to catch more of the deadly stakes (cf. Grond, the battering ram), even if the songs are still a bit silly (“Where There’s a Whip, There’s a Way”).

You’re right. The song was from the later R/B movie not the Hobbit – while Sam and Frodo were marching amongst the orcs. My mistake. I guess I’ll have to find the Hobbit to rewatch.

I think when asked to choose between the two adaptations, the proper response is: neither.

The Jackson trilogy is bloated and overstuffed, losing some of the heart out of the book and occasionally making it quite the dull slog. (I’m also not a fan when Jackson designates a character as the “comic relief” regardless of whether they were in the books or not, because they frequently end up getting nothing else)

The R/B has some lovely backgrounds, but I just can’t handle their character designs overall. I disagree that they don’t tilt too far into Disney; it’s as if they’d never conceived of anything but Disney Dwarves and the elves don’t work for me either. Too dopey, too silly.

The material is ripe for someone else to take a crack at it again, unburdened by previous efforts.

Anyone remember “Phil and Dixie” from Dragon Magazine? They once (or more) had a comic set in a fantasy convention with all sorts of geeky mayhem going on. One corner a man was getting an award for best miniature painting for “Gigantic Rampaging Ogre” – a big green scary thing two apples high. The award giver asked him if he had any secrets to share. “Multiple layers of paint.” “How many?” “1937..” (or something) “1937!?” “Yes, it started out as a halfling(hobbit minus copyright issues)….”

Just “One Man’s Opinion” but I consider the animated Hobbit a nearly perfect work. There’s always issues of if that, what if this…etc. But as near as perfection is allowed this is in the near target. The modern “Trilogy” is a grossly expensive bloated work like “Giant Rampaging Ogre”. I don’t say ill of it, I have them on Blu-Ray, watch through them once in a while, I love the art and filmmaking. This is versus a lot of modern re-makes and sequels I simply do NOT watch, buy, click…too burned out on that issue. Note I’m more a Dunsany fan than a Tolkien one, but do not disresepect JRR. Likewise I see the animated film as diminished while the Jackson trilogy is near PERFECT again to the “As close as possible IRL” to both honor the book and get new people or people who aren’t already fanatic Tolkien fans to appreciate him and perhaps become them.

I’ve heard of a “Phantom Edit” for the Hobbit – cramming it into one movie. Haven’t seen it yet, and I think it would have needed the original 60s era (yes 70s film but…) “Folk Songs” soundtrack or new ones. That it inspired South Park to evoke it and cause an interesting sway in names of class pets for a few years decades after it was made kind of argues how good an idea it was for the folk music.

I agree with you that, for all its flaws, the R&B version hews closer to the ‘feel and spirit’ of the book, although PJ’s may hew closer to the actual book (for including the Arkenstone sub-plot, if nothing else).

I can also say that, as a young man of 8 years old in 1977, the R&B version hit a bull’s eye with me. There were some odd choices re: the look of the goblins and the elves—although it wasn’t a deal-breaker.

Both the R&B T.V. show and the PJ theatrical releases suffered from the same problem: to tell the whole story on T.V. would be an awkward amount of time (although if you cut the ‘Greatest Adventure” song you probably could have worked in either the Beorn or the Arkenstone)—it needed to be more like 90 or 100 minutes—which is a weird amount of time for T.V. But for a theatrical release, 90 to 100 minutes seems a bit on the short side.

That said, I thought PJ had a good idea of padding out the story with material from the LOTR with Thorin’s history with the orcs of Moria, and the white council’s exploration of the lair of the necromancer. It was a good idea, but PJ didn’t quite do it justice in my opinion. And it seems he just went from having enough material for two movies to not-quite-enough for three.

I have a soft sport for the R&B ‘Return of the King’, although it wasn’t nearly as good as “The Hobbit”, in that it shows Sam picking up the ring and almost immediately falling under its sway—something that was conspicuously absent in the PJ movies. In the first two movies the ring is almost a character in and of itself and yet the most obvious scene to show just how seductive it is, just how it works (and thus a hint of what Frodo is constantly resisting), he didn’t show it- even though it came straight from the source material.

Great post, Bob! I absolutely agree.

Also, I’ve always said that the R-B rendition of THE RETURN OF THE KING would make a great foundation for a high school/college stage production of LotR.

[…] (Black Gate): J.R.R Tolkien’s 1937 children’s fantasy The Hobbit is one of the most beloved books in the […]

[…] of The Hobbit didn’t make a great case for it (Tolkien scholar Douglas A. Anderson called it “execrable”). But this didn’t stop Ralph Bakshi from trying to catch the whale with his ambitious 1978 […]