A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Will Murray and The Diamond Wager Caper – Not Dashiell Hammett?

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

(Gat — Prohibition Era term for a gun. Shortened version of Gatling Gun)

A (Black) Gat in the Hand makes its first-ever Friday appearance as Will Murray takes us down some Mean Streets never explored before. And he’s gonna need a blackjack and a roscoe in hand for this one. I’m not gonna spill the beans about Dashiell Hammett’s “The Diamond Wager”, but you’re definitely going to want to read on to find out the real truth behind that story. Take it away, Will!

____________________________________________

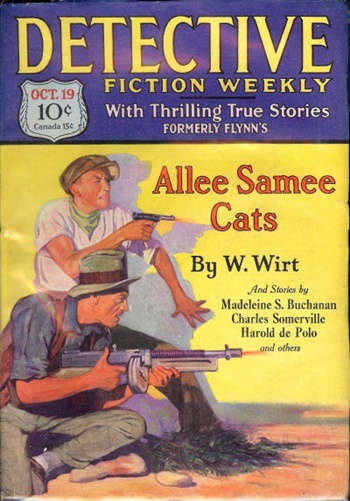

Recently, friend and fellow researcher Evan Lewis posted on Facebook the text of a story that first appeared in the October 19, 1929 issue of Detective Fiction Weekly entitled “The Diamond Wager.“ This was featured in a blogpost he originally posted in June, 2013.

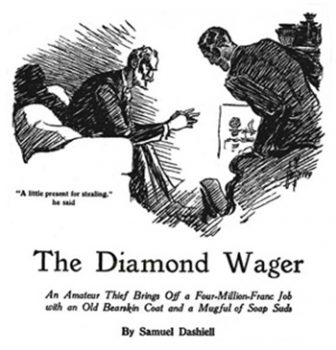

The story ran under the byline of Samuel Dashiell. According to Evan, it is widely believed to be the work of Samuel Dashiell Hammett, and constitutes Hammett’s only contribution to Detective Fiction Weekly.

“The Diamond Wager” is a 7,600 word yarn of a gentleman thief set in Paris. For a tale purportedly written by the author of The Maltese Falcon, it’s underwhelming. Opinions on the story’s worth do not vary much. When compared to Hammett’s oeuvre, it’s an oddball outlier, a tongue-in-cheek relic of the Golden Age of mystery stories.

The belief that this is a Dashiell Hammett story has over the last decade become so widespread that “The Diamond Wager” has been included in two reprint collections, including one all-Hammett volume curated by his granddaughter, The Hunter and Other Stories. There is also an ebook edition of “The Diamond Wager.” Other than the fact that it’s a crime story that involved diamonds, and Hammett had once written copy for a San Francisco jeweler, Samuel’s Jewelry, there is nothing suggestive of the former Pinkerton man in “The Diamond Wager.”

When I read Evan’s blog, I did a mental double take.

Didn’t I look into this long ago?

After I had thought about it, I realized, no, not really. I couldn’t recall ever hearing about, much less reading “The Diamond Wager.” What I was struggling to remember was that back in the latter 1970s when I was combing the bound volumes of Writer’s Digest at the Boston Public Library, I came across passing mention of a writer named Samuel Dashiell in an issue from the 1930s. At that time, I momentarily jumped to the identical conclusion that here was a variant byline for Samuel Dashiell Hammett.

But the context of the Writer’s Digest notation made it clear that Samuel Dashiell was a distinctly different personality entirely. This realization has stayed with me all these decades, hence my reaction familiarity to seeing that byline.

Fortunately, Writer’s Digest has been digitized and is available online. So I did a global search on the Internet Archive. I failed to locate any mention of Samuel Dashiell. I did find in the September, 1936 issue a reference to Sam Dashiell‘s forthcoming book on celebrity anecdotes:

Sam Dashiell relates many uncensored anecdotes and antics of such people as Walter Durante, Vincent Sheean and George Slocombe in his “Scandalous Chronicle“ which McBride will publish.

This appeared in David B. Hampton’s column, “The Writing World.”

An internet search failed to turn up any such published title. A book columnist mentioned the book’s imminent release in the Fall of 1936. The squib referred to Dashiell as “the international Winchell,” meaning broadcaster Walter Winchell. A later notice announced that the planned October release had been postponed. No book review surfaced. I suspect that it was never published.

I did however come across a 1943 non-fiction book credited to Samuel Dashiell, Victory Through Africa. This led me to various reviews of the book, which indicated that Samuel Dashiell was a United Press Association foreign correspondent who was working out of North African during the war.

I did however come across a 1943 non-fiction book credited to Samuel Dashiell, Victory Through Africa. This led me to various reviews of the book, which indicated that Samuel Dashiell was a United Press Association foreign correspondent who was working out of North African during the war.

The fact that David Hampton referred to Dashiell as “Sam” strongly implied that the man was a familiar face in the literary community of the Great Depression. My half-recollection that Samuel Dashiell was his own man was again coming into focus. I dug out my notebook from those library days and discovered that my memory had played me false. The reference I found back in 1976 was the one announcing Sam Dashiell’s Scandalous Chronicle. There was no other.

By that time, I had already popped over to newspapers.com and punched up his name. Newspaper articles by Samuel Dashiell stretched across decades and were too numerous to individually review. Many were datelined in various European capitals.

Samuel Dashiell was a ubiquitous newspaper byline during the first half of the 20th century. He became a roving staff correspondent for the United Press Association in the days before they were calling themselves United Press International.

Born in Wilmington, Delaware, in October 29, 1891, Samuel Lungren Dashiell’s newspaper career commenced in 1917. During World War I, he served stateside in the U.S. Naval Reserve Force. He also worked in Washington, serving in President Woodrow Wilson’s office.

During his long career, Dashiell traveled widely throughout Europe as a roving reporter, and served as the Italian representative for the Philadelphia Public Ledger as well as Paris correspondent for the Herald Tribune for several years during the 1920s and beyond. As a reporter, he covered virtually every international conference held between the world wars with distinction.

During World War II, he was with the Office of War Information in the U.S. and North Africa, where was in charge of broadcasts to North Africa and the Near East. From the spring of 1941 to early 1942, Dashiell was a war correspondent stationed in Algiers, until he was expelled under suspicion of being a British agent.

At the time of his death, Sam Dashiell was a civilian adviser to the Far East Command based in Tokyo. He died on June 26, 1949, at the age of 57. Like his fellow veteran, Dashiell Hammett, he was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Obituaries cite Victory Through Africa, but make no mention of Scandalous Chronicle, which might not have seen print. The celebrity trio mentioned in Writer’s Digest were all fellow newspaperman, two of whom also wrote fiction.

After his death, his friend Lamar Middleton wrote the following about Sam Dashiell’s colorful career:

“In the 1940 mass exodus from Paris, as the Nazis advanced, he dodged enemy bombs, making his way south on a bicycle. He escaped, and eventually was sent to Algiers, his third assignment to North Africa, when he was expelled by Vichy officials––an incident, incidentally, which he rightly considered the culminating point of his newspaper career.“

But does all this prove that newspaperman Samuel Dashiell and not Samuel Dashiell Hammett wrote the Detective Fiction Weekly story? As far as I’m able to determine, “The Diamond Wager” was Mr. Dashiell’s only pulp magazine sale. And it’s his only known fiction sale to the pulps.

Well, that’s not unusual by itself. Back in those ink-stained days, reporters of all stripes sold the odd fiction story now and again.

But the most telling thing was that in 1929, Samuel Dashiell was reporting from Paris, France. Paris was the setting of “The Diamond Wager.” In his own published fiction, Dashiell Hammett rarely strayed from his familiar San Francisco. Only one of his published stories was set in Europe, “This King Business.” The locale was the fictitious Balkan nation of Muravia.

Did I need more circumstantial evidence? I don’t think so. “The Diamond Wager” is currently considered to be Dashiell Hammett’s weakest published detective story. No surprise there. He didn’t write it.

Through a fluke inspired by their shared names, Dashiell Hammett’s byline became attached to the story. Obviously, this is a consequence of the same faulty leap in logic that I made nearly forty years ago.

While it’s not a stretch to imagine an unscrupulous pulp writer or his editor concocting a personal pseudonym out of Samuel Dashiell Hammett’s legal name in an attempt to gull the reading public, Munsey editors were not prone to such schemes.

While it’s not a stretch to imagine an unscrupulous pulp writer or his editor concocting a personal pseudonym out of Samuel Dashiell Hammett’s legal name in an attempt to gull the reading public, Munsey editors were not prone to such schemes.

The simple fact that “The Diamond Wager” was never reprinted under Hammett’s name is an additional piece of circumstantial evidence that he had nothing to do with it.

This is not the first time such a literary misadventure has occurred in the field of mystery fiction. Back in 1948, an unpublished Sherlock Holmes story was discovered among the papers of the late Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. “The Man Who was Wanted” was swiftly published amid great publicity in Cosmopolitan and elsewhere as a long-lost adventure of the Great Detective.

While the story was disappointing to many, it was hailed as a fabulous find.

Subsequently, the tale’s true author, one Arthur Whitaker, stepped forward to claim authorship. He had sent the manuscript to Conan Doyle when the latter was still living and was paid for the right to use the plot, which Doyle never did. (BB – You can read more about that in this Black Gate essay)

The events surrounding “The Diamond Wager” are a parallel case of a regrettably embarrassing but someone understandable literary misattribution.

Some might question whether a Paris-based newspaperman would be submitting to Detective Fiction Weekly in New York City, but a decade later in 1938, when writer Steve Fisher was living in Paris, he was happily air-mailing manuscripts to Street & Smith and other magazine markets, living comfortably off his sales.

The Munsey Publishing Company’s canceled checks survive to this day. Unfortunately, thanks to the author signatures found on their backs, many were sold off as collectibles in recent decades. The current owner of the Munsey records, Matthew Moring of Steeger Books, told me he didn’t recall coming across it among the checks still in his custody. He believes it may have been sold off years ago. Absent the signed check for “The Diamond Wager” resurfacing, I’m confident that the signature on the back will not match that of Dashiell Hammett. I’m equally confident that it was cashed through a Parisian bank.

The New York Public Library houses a portion of the Popular Publications payment records, which includes Munsey material, which they acquired in 1940. I’ve delved into them myself. Perhaps the definitive answer can be found there.

So where did this misinformation originate?

According to Evan, back in the 1968, a Kent State University book by E. H. Mundell, A List of Original Appearances of Dashiell Hammett’s Magazine Work, included the story title and bibliographic details, positing that Samuel Dashiell was a previously-unknown pseudonym for Dashiell Hammett.

The following year, William F. Nolan listed it without qualification or reservation in his Dashiell Hammett: A Casebook.

Since then, various bibliographers and biographers have taken that tentative assertion from a half-century ago and run with it. It’s in Richard Layman’s 1981 biography, Shadow Man as a fact.

Regrettably, it’s not true.

Later Hammett biographies, Nolan’s Hammett: A Life at the Edge, Diane Johnson’s Dashiell Hammett: A Life, Sally Cline’s Dashiell Hammett: Man of Mystery, and Nathan Ward’s The Lost Detective: Becoming Dashiell Hammett, are silent on the subject.

The faulty chain of authorial association truly got out of hand when in June, 2013, Evan Lewis first posted “The Diamond Wager” on his blog site, Davy Crockett’s Almanack of Mystery, Adventure and the Wild West.

Lewis told me how he came by the text:

“After years of looking, I got the magazine on microfilm from the Library of Congress, and printed pages on a machine at the public library. Those pages were very muddy, and some words nearly indecipherable. One word stumped me completely, but the context told me it had to be either ‘Mr.’ or ‘Alex.’ I chose ‘Mr.’, but it was a near thing. The pulp story also had several typos in punctuation, and one instance where I had to change the name of one character to another.”

That same year, “The Diamond Wager” was reprinted in a mass market collection, The Mammoth Book of Pulp Stories, edited by Maxim Jakubowski, who credited the rediscovery of the text to “internet detectives.”

Clearly, Jakubowski meant Evan Lewis, whose editorial alterations were carried over into his collection.

Months later, Peril Press took it upon themselves to extract the story and offer an e-book edition, presumably retaining Lewis’s edited text.

This culminated in the inclusion of “The Diamond Wager“ in The Hunter and Other Stories later in 2013, again employing Lewis’ text. This collection of miscellany was edited by Hammett’s granddaughter, Julie M. Rivett and Hammett biographer, Richard Layman.

All of this was done despite the fact that the text is still under copyright. But this is incidental. What had started as a mere academic supposition had, through repetition, hardened into a kind of false fossil.

In his introduction to The Hunter and Other Stories, Richard Layman suggested that “The Diamond Wager” was the unnamed Hammett story rejected by Blue Book in 1927, and finally placed with Detective Fiction Weekly two years later. It’s a reasonable theory, but it’s more probable that the rejected manuscript was “This King Business,” whose first appearance was in Mystery Stories, January, 1928, which would have gone on sale late in 1927.

Yet I can see where reading the opening line of the story might lead one to suspect Hammett’s hand:

“I always knew West was eccentric.”

But after that, the narrative goes downhill fast. The tone is the opposite of hardboiled. It’s more of a throwback to Maurice LeBlanc’s Arsene Lupin stories, but without that writer’s panache. It was also typical of DFW’s usual pulpy contents, stylistically and otherwise.

As Hammett scholar Don Herron once put it, “If you didn’t know Hammett wrote it, you’d never know Hammett wrote it.”

Some have suggested that “The Diamond Wager” is Hammett’s attempt to lampoon the likes of E. W. Hornung’s Raffles stories. But that’s a pretty wild reach, and ultimately unsupportable in theory as well as in fact.

Hammett was certainly familiar with the types of detective fiction that preceded his narrative revolution in storytelling. He reviewed the works of Carolyn Wells and R.T.M. Scott, but without enthusiasm. He is unlikely to have turned his emerging skills in such a retrograde direction.

It’s certainly not implausible that during the stretch of months in which The Maltese Falcon was first serialized, Dashiell Hammett might have attempted to write a different kind of detective story for a different market than Black Mask, and adopt a thinly-veiled pen name for the occasion. But in doing so he would still be Hammett. Just as he was unmistakably Dash Hammett when he wrote The Thin Man, which is a 45° angle departure from The Glass Key.

Dashiell Hammett would not have produced this species of prose:

Ever since the days of our youth, in various universities—for we seemed destined to follow each other about the globe—I had known Alexander West to be a person of the most bizarre, though not unattractive, personality. At Heidelberg, where he renounced water as a beverage; at Pisa, where he affected a one-piece garment for months; at the Sorbonne, where he consorted with the most notorious characters, boasting an acquaintance with Le Grand Raoul, an unspeakable ruffian of La Villette.

And in later life, when we met in Constantinople, where West was American minister, I found that his idiosyncrasies were common topics in the diplomatic corps. In the then Turkish capital I naturally dined with West at the Legation, and except for his pointed beard and Prussian mustache, being somewhat more gray, I found him the same tall, courtly figure, with a keen brown eye and the hands of generations, an aristocrat.

But his eccentricities were then of more refined fantasy. No more baths in snow, no more beer orgies, no more Libyan negroes opening the door, no more strange diets. At the Legation, West specialized in rugs and gems. He had a museum in carpets. He had even abandoned his old practice of having the valet call him every morning at eight o’clock with a gramophone record.

Are you kidding me? Where are the crisp, declarative sentences? The innate objectivity? The lean and laconic Hammett personality shining through it all? All such stylistic indicators are conspicuously absent, as they are in this turgid passage:

It was some years later, however, when West had retired from diplomacy, that he turned up in my Paris apartment, a little grayer, straight and keen as usual, but with his beard a trifle less pointed—and, let’s say, a trifle less distinguished-looking. He looked more the successful business man than the traditional diplomat. It was a cold, blustery night, so I bade West sit down by my fire and tell me of his adventures; for I knew he had not been idle since leaving Constantinople.

“No, I am not doing anything,” he answered, after a pause, in reply to my question as to his present activities. “Just resting and laughing to myself over a little prank I played on a friend.”

“Oho!” I declared; “so you’re going in for pranks now.”

He laughed heartily. I could hardly see West as a practical joker. That was one thing out of his line. As he held his long, thin hands together, I noticed an exceptionally fine diamond ring on his left hand. It was of an unusual luster, deep set in gold, flush with the cutting. His quick eye caught me looking at this ornament. As I recall, West had never affected jewelry of any kind.

There’s that affected word ‘affected’ again.

Dash Hammett would never have produced such floridity on his drunkest day. To believe that this is the work of the author of Red Harvest defies logic. It’s also an example of the power of suggestion resulting in severe cognitive bias. Duped by the suggestive byline and reliably informed that “The Diamond Wager” came from Hammett’s typewriter, readers and scholars alike ignored the evidence of their senses, leading to the willing suspension of their otherwise sound critical judgment. Every Hammett fan wanted more Hammett, and the scanty “evidence” that here was a long-lost story proved irresistible to everyone and everything—including common sense.

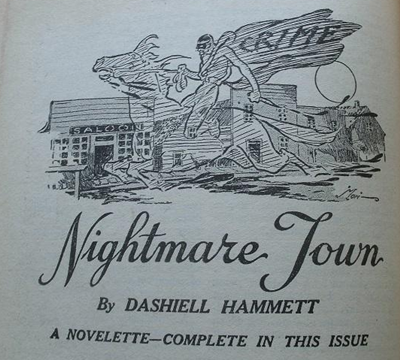

Dashiell Hammett was obviously not afraid to experiment. Nor did he have such a high opinion of his own work that he would be afraid to write for a magazine considered to be a step beneath Black Mask. Back in 1924, “Nightmare Town” first appeared in another Munsey magazine, Argosy All-Story. Still other Hammett detective tales had run in such downmarket magazines as True Detective Stories, Mystery League Magazine, and Mystery Stories.

Dashiell Hammett was obviously not afraid to experiment. Nor did he have such a high opinion of his own work that he would be afraid to write for a magazine considered to be a step beneath Black Mask. Back in 1924, “Nightmare Town” first appeared in another Munsey magazine, Argosy All-Story. Still other Hammett detective tales had run in such downmarket magazines as True Detective Stories, Mystery League Magazine, and Mystery Stories.

Nor was it unusual for a pulp writer to lop off one of his names in order to concoct a pseudonym. Did Samuel Dashiell Hammett not discard his first name for his professional byline? Deleting his last name for a pen name is imminently plausible. Here, however, that is not the case. What would be the point of Hammett obscuring his true identity by reverting to his first name? If he wished to create a separate writing identity, why simply resurrect the pen name under which first broke into print, Peter Collinson? Most tellingly, he would have avoided choosing a byline belonging to a foreign correspondent coming into international prominence just as his own literary career was taking off.

Furthermore, Readers of 1929 would not know that Dashiell’s Hammett’s first name was Samuel, so this could not be an editorial attempt at creating a fictitious doppelgänger of a famous contributor, as Fiction House sometime did when they ran pseudonymous stories under bylines calculated to evoke the names of prominent pulpsters.

No, Samuel Dashiell is a coincidentally parallel name.

Due to a combination of poor finances and his drinking habits, Hammett at times wrote simply for the money. A story I heard from one of his contemporaries was that Hammett needed an advance and Black Mask editor Joe Shaw was willing to voucher for a check in return for a serial title the magazine could advertise as forthcoming.

On the spot, Hammett offered up The Glass Key. That was good enough for Shaw. Turning in each installment before deadline, Hammett realized that he needed to justify the unique title in some way.

Struggling with the problem, he came up with the idea of a glass key appearing as a symbol in a dream. It was perhaps lame, but what else could he do?

An admirer recalled complimenting Hammett on The Maltese Falcon. To which the author growled in reply, “Yeah, it was a good job of carpentry.”

But Hammett was a craftsman, and selling a substandard story to a lesser market doesn’t seem to fit the temperament of the man, as his contemporary, James H. S. Moynahan, described him in 1936:

“Dashiell Hammett, after a long, bitter climb that too few people know about, has attained to the point where he can now write almost as he wishes. Perhaps it was his unique sense of humor that saw him through the dark days in San Francisco when, despite what the money might have meant to him then, he tore up thousands of salable words because they did not suit him.”

Just to be thorough, I reached out to Don Herron to ask if the original manuscript to “The Diamond Wager” survived among Dashiell Hammett’s papers housed in the Harry Ransom Center located at the University of Texas, Austin. Don replied, “I don’t know for sure, but would say no,” and provided the following clarification:

“It was published. Like many other pulp writers, Hammett kept various unsold typescripts around, but once they were sent off and sold to a publisher he got his contributor’s copies and pulled out tear sheets to use in the future––as in the early Op book Including Murder.”

Including Murder was an unsold collection of Hammett’s Black Mask stories the author assembled out of magazine tear sheets in the mid-1920s. Herron continued:

“All very much the norm––the materials that ended up in Texas doesn’t include any published original manuscripts. Even the long galley sheets Hammett hand-corrected for The Dain Curse seem to have been sent back after typesetting and were kept by his wife. Hammett would have tossed them.”

Evidently, no tear sheets of the printed “Diamond Wager” exist in those files, either. Otherwise, the story would have certainly been reprinted long before it was, if only as a curiosity.

For those who might yet be clinging to some shred of doubt by imagining that Dashiell is a rather rare name to encounter twice in that Prohibition era of publishing, the managing editor of Scribner’s Magazine during that time was Alfred Dashiell.

Nor was Samuel Dashiell unique. Two months after the author by that name died, another Samuel Dashiell made headlines when he and his wife—exchange teachers from Washington State—got caught up in a civil war in Burma, falling captive to the Karen rebel group, along with other Americans. By the end of August, diplomatic efforts had won their release.

I love to discover new things about classic pulp writers. Sadly, this is more in the line of an “undiscovery.” Samuel Dashiell’s “The Diamond Wager” can now confidently deleted from Dashiell Hammett’s bibliography. And in doing so remove a kind of literary stain from his reputation. I’m sure some Hammett scholars will be relieved to jettison this sorry and ill-fitting yarn forever.

For those interested in exploring further, here is a link to the story:

Read it for yourself and try to imagine Dashiell Hammett composing it. I can’t. Because he didn’t.

A thought occurs to me. It’s far-fetched, perhaps. But the writing careers of both Dashiell Hammett and Samuel Dashiell took off in the early 1920s. I wonder if seeing Samuel Dashiell’s byline so frequently in the newspaper might not have motivated Samuel Dashiell Hammett to abandon his first name in print, lest his work be confused with his newspaper counterpart and namesake? Stories filed from France bearing Dashiell’s byline appeared in American papers from 1922 onward in great numbers. Alternately, this might have inspired Hammett to emphasize the shared the name of Dashiell.

Finally, I feel sorry for all the Hammett collectors who have over the last decade or so paid a premium for the October 19, 1929 issue of Detective Fiction Weekly. Copies have sold for hundreds and, in cases of bidding wars over top-condition examples, more than a thousand dollars for a copy of that otherwise utterly random and unremarkable issue of the long-running title.

Prior Posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2023 Series (1)

Back Down those Mean Streets in 2023

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2022 Series (16)

Asimov – Sci Fi Meets the Police Procedural

Asimov – Sci Fi Meets the Police Procedural

The Adventures of Christopher London

Weird Menace from Robert E. Howard

Spicy Adventures from Robert E. Howard

Thrilling Adventures from Robert E. Howard

Norbert Davis’ “The Gin Monkey”

Tracer Bullet

Shovel’s Painful Predicament

Back Porch Pulp #1

Wally Conger on ‘The Hollywood Troubleshooter Saga’

Arsenic and Old Lace

David Dodge

Glen Cook’s Garrett, PI

John Leslie’s Key West Private Eye

Back Porch Pulp #2

Norbert Davis’ Max Latin

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2021 Series (8)

The Forgotten Black Masker – Norbert Davis

Appaloosa

A (Black) Gat in the Hand is Back!

Black Mask – March, 1932

Three Gun Terry Mack & Carroll John Daly

Bounty Hunters & Bail Bondsmen

Norbert Davis in Black Mask – Volume 1

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2020 Series (19)

Hardboiled May on TCM

Some Hardboiled streaming options

Johnny O’Clock (Dick Powell)

Hardboiled June on TCM

Bullets or Ballots (Humphrey Bogart)

Phililp Marlowe – Private Eye (Powers Boothe)

Cool and Lam

All Through the Night (Bogart)

Dick Powell as Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar

Hardboiled July on TCM

YTJD – The Emily Braddock Matter (John Lund)

Richard Diamond – The Betty Moran Case (Dick Powell)

Bold Venture (Bogart & Bacall)

Hardboiled August on TCM

Norbert Davis – ‘Have one on the House’

with Steven H Silver: C.M. Kornbluth’s Pulp

Norbert Davis – ‘Don’t You Cry for Me’

Talking About Philip Marlowe

Steven H Silver Asks you to Name This Movie

Cajun Hardboiled – Dave Robicheaux

More Cool & Lam from Hard Case Crime

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2019 Series (15)

Back Deck Pulp Returns

A (Black) Gat in the Hand Returns

Will Murray on Doc Savage

Hugh B. Cave’s Peter Kane

Paul Bishop on Lance Spearman

A Man Called Spade

Hard Boiled Holmes

Duane Spurlock on T.T. Flynn

Andrew Salmon on Montreal Noir

Frank Schildiner on The Bad Guys of Pulp

Steve Scott on John D. MacDonald’s ‘Park Falkner’

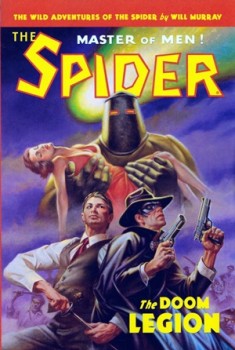

William Patrick Murray on The Spider

John D. MacDonald & Mickey Spillane

Norbert Davis goes West(ern)

Bill Crider on The Brass Cupcake

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2018 Series (32)

George Harmon Coxe

George Harmon Coxe

Raoul Whitfield

Some Hard Boiled Anthologies

Frederick Nebel’s Donahue

Thomas Walsh

Black Mask – January, 1935

Norbert Davis’ Ben Shaley

D.L. Champion’s Rex Sackler

Dime Detective – August, 1939

Back Deck Pulp #1

W.T. Ballard’s Bill Lennox

Day Keene

Black Mask – October, 1933

Back Deck Pulp #2

Black Mask – Spring, 2017

Frank Schildiner’s ‘Max Allen Collins & The Hard Boiled Hero’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Campbell Gault

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: More Cool & Lam From Hard Case Crime

MORE Cool & Lam!!!!

Thomas Parker’s ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’

Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part One)

Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part Two)

William Patrick Maynard’s ‘The Yellow Peril’

Andrew P Salmon’s ‘Frederick C. Davis’

Rory Gallagher’s ‘Continental Op’

Back Deck Pulp #3

Back Deck Pulp #4

Back Deck Pulp #5

Joe ‘Cap’ Shaw on Writing

Back Deck Pulp #6

The Black Mask Dinner

There are some outstanding names in the ‘New Pulp’ field, but William Patrick Murray’s probably stands above them all. Along with Doc Savage, Will has written Tarzan and The Spider. And he’s quite the Sherlock Holmes writer. Short stories, comic books, radio plays, nonfiction essays and books – Murray has done it all. He created The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl for Marvel Comics, and his collection of essays on Doc Savage, Writings in Bronze, is a must read. I love a good book introduction, and Murray has written some fine ones for Steeger Books. Visit his website Adventures in Bronze.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE 5-star reviewed, Definitive Guide to Conan. He also organized 2024’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, and XXXIII, and an upcoming volume.

He writes introductions to pulp collections and novels from Steeger Books, and has appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

To be fair, I bought my copy of that October 19, 1929 DFW to read the W. Wirt story…

Excellent article Will. Fortunately I spent only $1.25 for a copy of the 1929 DFW back in 1970. A lot of pulp collectors are going to be unhappy to see the worth of the DFW nosedive!

Fascinating stuff. Thanks for doing the work on this, Bob.

This was ALL Will. He was kind enough to want to run it in A (Black) Gat in the Hand. I claim (and deserve) no credit, other than helping him get it out there quickly.

He really put together a neat case. With my memory these days, I doubt I would even have remembered researching stuff at the Boston library years before!

Quite a piece of detective work, Bob! (Columbo, Holmes and Spade will all be nodding in quiet approval, no doubt).

As I mentioned in a reply above, this was 100% Will Murray. We just ran it in my Pulp column here at Black Gate. That was my contribution. He really put together a solid case. And he didn’t even get blackjacked in a dark alley.

Well, not yet. Owners of that copy of DFW may do that later.

🙂

Oh, man – helpless Doc Savage junkie that I am, I have GOT to get Writings in Bronze. The only question is – which of my children’s college funds will I steal from this time?

Great job, Will. I had my doubts when you first suggested this, but your research is mighty dang impressive, and you lead us gently into the idea before punching us in the nose with it. I doubt you’ll get many arguments. One quibble – old EH Mundell in his 1968 book actually said the story was “believed by some to be a psuedonym of” Hammett, so he may deserve a little less blame.

[…] can read all about it in this post on the Blackgate blog. Will Murray’s account there seems definitive to me. All the collectors who have paid a steep […]

Actually, all three of those journalists wrote fiction. George Slocombe, of the UK, penned a couple of speculative novels, Dictator and Escape into the Past. The novels of Walter Duranty and Vincent Sheean were better known.

The truth is, much of Walter Duranty’s journalism was fiction, as in his notorious whitewashing of conditions in the Soviet Union (his fawning cover-up of Stalin’s Ukrainian terror-famine was beyond disgraceful).

[…] can read more about the case in an excellent essay by Will Murray, guest-writing in Bob Byrne’s blog. If you’re disappointed by the dearth of detective stories in “The Hunter and Other Stories,” […]