Talking Tolkien: The Singularity of Vision in Tolkien’s Middle-Earth – By Gabe Dybing

Talking Tolkien took a break last week so my annual Summer Pulp series, A (Black) Gat in the Hand, could pop in. But we’re back to the Professor this week. Gabe Dybing and I talk about RPGing on the side – we even started a short-lived Conan campaign. So I was thrilled when I conned him into…I mean, he agreed to contributed a post on MERP. If you don’t know what MERP is, read-on. Those were some terrific RPG books.

Talking Tolkien took a break last week so my annual Summer Pulp series, A (Black) Gat in the Hand, could pop in. But we’re back to the Professor this week. Gabe Dybing and I talk about RPGing on the side – we even started a short-lived Conan campaign. So I was thrilled when I conned him into…I mean, he agreed to contributed a post on MERP. If you don’t know what MERP is, read-on. Those were some terrific RPG books.

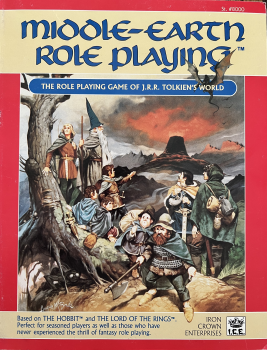

I have decided to take “Discovering Tolkien,” the title of this series, as my means of entry into the subject. By doing so, I can only hope that I happen to make (if not “new”) interesting or sideways observations about Tolkien’s awe-inspiring achievement. And this approach moreover gives me the opportunity to address a subject that this series’s editor has wanted me to handle, which is the nature of Iron Crown Enterprises’s (I.C.E.’s) Middle-Earth Role Playing (MERP), specifically the 1987 edition that I purchased at Waldenbooks in the Eden Prairie Center in Eden Prairie, Minnesota, a game that, incidentally, also introduced me to roleplaying in general.

Some may feel that I add too much detail, by citing precisely where I bought MERP, but I expect that I may find some sympathy with others who are perhaps about my own age – this year I am approaching age 48. These details, the milieu in which I discovered Tolkien, are inextricably bound together with the experiences of reading and re-reading this masterwork of English Language and Literature. They also inform the ways in which I continued and continue to explore this achievement through other media.

Let me pause for a moment on “incomparable.” I don’t want to be misunderstood: of course I can compare all manner of worlds and works to Tolkien’s Middle-earth, but, in my view, none will “measure up.” In many ways, my discovery of Tolkien in the fifth grade began a lifelong and – to this day – never ending quest to discover it again, and I don’t think I ever shall.

That’s not to say that some works haven’t come close. I don’t intend to be “critical” in this essay, so please let me deal glancingly with the productions that most obviously were meant to imitate Tolkien.

Terry Brooks’s works, though dressed appropriately, hammer tonelessly through Tolkien’s same story beats and, more oddly, characterization. As an example of the latter, I submit the unwillingness of Brooks’s characters to “trust” the Druid Allanon presumably for no better reason than that some of Tolkien’s characters didn’t trust Gandalf.

As an imitation, for me, Stephen R. Donaldson’s The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant doesn’t even rate, because, in these works, the entire soul of Tolkien’s masterpieces are subverted by a central figure who is an agnostic, misanthropic, and sociopathic anti-hero.

In my youth, these two productions were the most available to me, through the local library, and their trade dresses telegraphed to me that they were to be most like Tolkien. But the former I found to be without substance, the latter I found to be odious. Incidentally, Tom Shippy, in Tolkien: Author of the Century, spends some time on these productions as imitations of Tolkien. A last work that he does not merely list (as he does some others) is The Weirdstone of Brisingamen, which, alas, I have not read, so I end this brief and dismissive discussion here.

Instead, writers that have come closer to Tolkien’s achievement, for me, don’t necessarily have the appearance of Tolkien but his spirit. Examples include the whole of the Inklings – the Inklings, in case it is not known, is the literary club founded by Tolkien’s friend C.S. Lewis and at whose meetings many chapters of The Lord of the Rings and other works by Tolkien and manuscripts by other members were read in draft. The productions recited include works by C.S. Lewis and Charles Williams. I also have found a whisper of Tolkien in predecessors to the Inklings’ works, in writings by George MacDonald and G.K. Chesterton, and, into our contemporary era, productions by Gene Wolfe, Frederic S. Durbin, and James Stoddard. This quick survey shows that what I believe to be most lacking in Tolkien’s apparent imitators is an anima, even when that worldbuilding (or, as Tolkien would say, “subcreation”) can be exemplary.

So there it is. I have stumbled into a secondary thesis. For me, the works of Tolkien are without peer because of their spiritual – perhaps I should say “religious” – dimension. Early and iterative readings of The Lord of the Rings taught me the weight of internal and external Evil and the means by which these can be overcome. Again, I do not pretend that I’m going to say anything new. Instead, read Tom Shippey on Manichaean and Boethian conceptions of Evil, or Joseph Pearce’s Tolkien: A Literary Life, about just how thoroughly Tolkien’s Catholic faith infused his works, both of which recently I reread thinking they would prepare me for this essay. But it was Tolkien who first showed me a world with true stakes, one in which you fight against hopeless odds simply because it is the right thing to do – not because there is any hope of actually achieving a victory. Nay, the heroes of Tolkien’s masterpieces fight for doomed causes, and their struggles are the results of pure selflessness, or, as Shippey puts it, the “Theory of Courage.”

But there also is Tolkien’s corollary, what he calls “eucatastrophe,” in his essay “On Fairy Stories,” that, even when the cause seems hopeless, it may not in fact be so, for not even the very wise can see all ends. Aragorn brings hope to Men but keeps none for himself. And yet he survives to be wed to his love and to be crowned King of Men, because of a sudden and unexpected turn of good fortune in the War of the Ring.

A key aspect to this religious sense is the concept of the numinous. Tolkien’s tales in Middle-earth are set in a time not far removed from the conjectural and philosophical Judeo-Christian “Fall.” As such, in The Lord of the Rings and in other works set in that – our – cosmos, humanity hasn’t entirely forgotten the pre-Fall language of creatures who are other than themselves, and – most wondrously – they still inhabit a world with them. In fact, in the Third Age of Tolkien’s Middle-earth, much of the landscape still is populated with people who are “greater” than Men.

I think it was this feature of Tolkien’s works, above all others, that excited me as a child. In the midst of my comfortable upbringing in a Minneapolis suburb, I wanted nothing more than to somehow Escape into Middle-earth. This psychological dimension, examined with sympathy and approval in Tolkien’s “On Fairy Stories,” is what motivated me most in my childhood and in my youth and in my young adulthood and still now, in my more settled middle age, to explore fantasy worlds. Tolkien, writing of his childhood, said that he had a deep and profound desire for dragons. I had a deep and profound desire for Tolkien’s own Middle-earth, and I intended to get there – and dwell there – by any means I could.

I intended to journey into that realm by reading and rereading the books, of course. By the time I finished high school, I had lost precise count of how many times I had read The Fellowship of the Ring specifically (my most favorite of the “trilogy,” because it deals the most with “faerie” – the idle, Hobbit countryside; the first interactions with the Elves; Tom Bombadil – anecdotally the least favorite aspects of the work among other enthusiasts).

Another way to get into that world was to seek it in my own. The backyards of every residence in my cul-de-sac were bound by woodlots, and I ranged them, climbing trees, blazing trails, crossing Purgatory Creek on the back of a fallen log that spanned its length. I fashioned swords out of oak, and bows out of willow and string. This is the process that Tolkien calls Recovery, that, when a reader immerses that one’s psyche in fictive forests inhabited by Elves and other enchantments, just a bit of that glamor is carried back with that person into the “real world.” “Real” forests are just a little more magical because of one’s imaginative experiences in fantasy.

I imitated Tolkien in my own work. In fifth grade I was drafting my “own” epic. It was about seven dwarves on a quest to rescue their mountainous homeland from a usurping dragon. There was no Hobbit in the work, so it was wholly original! (I’m being facetious here, of course!) I abandoned it, but soon began another, and another, and another “great work.” Every year I started a new “Lord of the Rings,” until I became conscious of just how long Tolkien’s shadow is and how impossible it is for me to get out from under it.

And I discovered MERP.

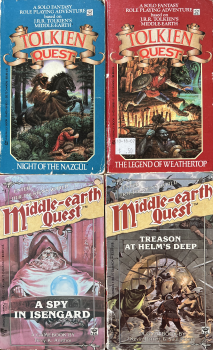

Many who give their rpg narratives cite a mentor – almost invariably an older sibling or a neighborhood friend – who discipled them in this arcane lore that quite often is specific to sharing the secrets of Dungeons & Dragons. But I had to discover roleplaying for myself, from a deep desire to somehow get even more into Middle-earth than just by rereading the “trilogy.” And I must have done so by standing in Waldenbooks at the Eden Prairie Center and studying the various products available on the shelves. I’m not sure on what I chose first to spend my hard-earned money: The Fellowship of the Ring board game or Night of the Nazgul, this latter a solo “game book” set in Tolkien’s world. I expect I wouldn’t be wrong if I merely went by the dates of publication on these two titles, because, as I am confirming through these reminiscences, I appear to have been getting into this discourse exactly as Middle-earth gaming materials were hitting the shelves. How fortuitous! What an apparent accident that I.C.E. was publishing precisely during my own awakening and lifelong interests! Or, as Gandalf might say, perhaps it was “meant” to happen this way.

Before actually publishing MERP, I.C.E. obtained permission to produce Middle-earth materials for its own rules set, Rolemaster, which was a collection of house rules for Advanced Dungeons & Dragons that bloomed functionally into its own percentile game system. Because MERP, a stripped-down version of Rolemaster, wasn’t out yet, one of those days when I was perusing Waldenbooks – or because I just hadn’t noticed MERP on the shelves yet – I bought the first Middle-earth rpg supplement, Angmar: Land of the Witch King, thinking it somehow had something to do with the Fellowship of the Ring board game I owned. And I tried to use it in the game! Remember, I already have said I was trying to figure all of this out on my own, and I was twelve years old!

Slowly, however, and with the purchase of MERP in 1987, things began to take shape for me. I learned that Angmar, for one, functioned better with MERP, though I still was puzzled by some of the names of professions in the supplement, because they were Rolemaster professions, and MERP had only six. And Angmar mentioned another system of magic, Mentalism, which wasn’t in MERP, as far as I could determine.

I think I need to take some space here to describe MERP, just in case anyone wants to hear my thoughts on Tolkien and how his achievements relate to gaming, but doesn’t know much about the game itself. It should be noted that there have been more than a few iterations of Middle-earth gaming since MERP, but MERP – or Rolemaster, rather – was the very first. And this very first system was itself heavily influenced by Dungeons & Dragons, which already has been noted, because the people who made up I.C.E. first used AD&D to adventure in Tolkien’s setting.

As I have pointed out, the first Middle-earth rpg supplements that I.C.E. published were for the much more expansive and simultaneously “fantasy generic” Rolemaster. But, when it came to be published, MERP was a more concise version of Rolemaster containing attempts at being more faithful in tone and lore to Tolkien’s setting. It’s important to point out that this era of gaming was dominated by “simulationism.” Later games would more consciously seek to emulate, through their mechanics, the feeling of an intellectual property, and it can be argued that the latest licensed rpg of Tolkien’s world, The One Ring 2e, by Free League Games, is motivated by precisely this. But when MERP was constructed, its chief aim was to simulate the physical characteristics of “reality” through mechanics and probabilities, and the ethos and mythos of Tolkien’s intellectual property were very much secondary concerns.

So, when Rolemaster was “right-sized” to MERP, rather than remaining an overly expansive collection of tools for gaming in that world, it returned, by some measures, to its roots in D&D. Characters now were defined by six (well, seven, if you count Appearance in any way relevant to gameplay – players of MERP will know what I mean) attributes that correspond precisely to the six well-known in D&D. Unlike D&D, however, MERP’s core mechanic remained Rolemaster’s percentile dice roll.

The comparisons between MERP and D&D can go on and on, mostly because D&D itself borrows from Tolkien’s works. But, if D&D contains dwarves, elves, and halflings as playable “races,” MERP delves much, much deeper into their types and canonical lore – at least this was true back in 1987. Appendix 1 of the MERP rulebook gives fascinating and lavishly detailed profiles and sketches of the various races, and these are highly informed by the rulebook’s authors’ close readings of Tolkien’s texts. It’s also possible that there is some invention in these descriptions – I have not taken the writing of this essay as cause to reread them with careful attention – a criticism that some of the I.C.E. Middle-earth supplements have received, particularly in regards to the famous The Court of Ardor in Southern Middle-Earth, which features “evil Elves.” But I don’t find them any more egregious than the generally “better sanctioned” The One Ring materials I have read. In fact, in my youth, I readily took I.C.E.’s depictions and formulations as “canonical Tolkien,” and I may have accepted all of it had I been able to afford more than just the half-dozen or so supplements I managed to collect in my early days of gaming.

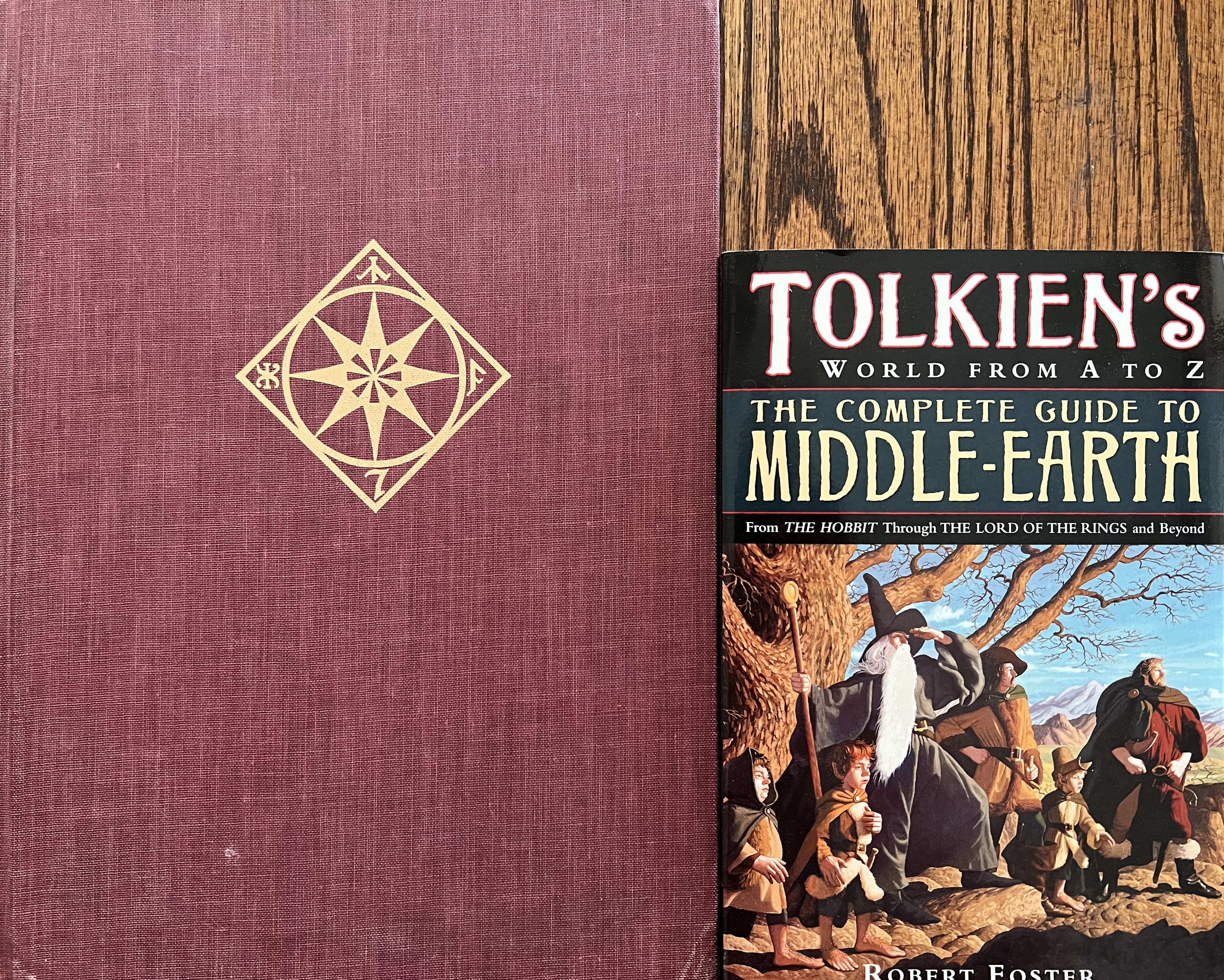

Instead of the full line of MERP materials, my chief gaming resources outside of the core book were Karen Wynn Fonstad’s The Atlas of Middle-Earth and Robert Foster’s Tolkien’s World from A-Z: The Complete Guide to Middle-Earth.

If one, judging by its place in history, is able to forgive MERP for being overly simulationist of “reality” rather than emulationist of the tone and spirit of the Tolkien property, a criticism that is more difficult to minimize is MERP’s magic system. MERP contains a number of spell-casting professions, all of which have their analogues in D&D that, again (especially in the case of the Ranger), also circuitously are drawn originally from Tolkien. Moreover, in MERP, as in D&D, are two sources for magic: nature and the gods or beneficent spirits and the elemental manipulation of cosmic forces themselves. These forms of overt and spectacular wizardry is many’s first objection to MERP as particularly reflective of Tolkien’s actual depiction of magic in his works, though many also defend this inclusion both through specific and esoteric references to Tolkien’s works themselves and through the practical considerations that some gamers just want their characters to be able to perform arcane spells.

And a last observation should be made on the simulationist nature of combat in the game, and this is combined, at times, with a sardonic sense of humor that is undoubtedly carried forward from its source in Rolemaster, which can read at odds with Tolkien’s sympathy and reverence for the plight and struggles of the Free Peoples. The MERP combat system uses critical hit tables that contain results such as “Stumble over an unseen imaginary deceased turtle. You are very confused” or “Worst move seen in ages. … Foe is stunned … laughing” or, what we young ones quoted most often, “Blast annihilates entire skeleton. Reduced to a gelatinous pulp. Try a spatula.”

The truth is that MERP is a fine rpg system that was made to work with Tolkien’s Middle-earth. I.C.E.’s supplementary lore materials are inspired and consonant, if not always “canonical,” and the artwork – many covers by Angus McBride and maps by Peter Fenlon – indelibly and wondrously informed my own conceptions of Middle-earth just as much as did Christopher Tolkien’s own maps in the books themselves and the covers by Darrell K. Sweet in my era’s editions of The Lord of the Rings.

But the greatest obstacle I have found in gaming an emulation of Middle-earth is not the system so much as what the group wants out of the Middle-earth experience.

You see, I have played and put aside the last two editions of the latest licensed Middle-earth rpg, The One Ring. Instead, I play in a campaign of Against the Darkmaster, which in part is a retroclone of MERP, also an emulation of the entire 1980s fantasy novel, film, and music milieu. What many people argue about playing in a defined intellectual property setting – from Star Wars to Middle-earth – is what to do with canon and the assumption that – unless the group is going to turn the entire established narrative into malleable toys to do with as it wills – the player characters never can alter canonical world events. There are plenty of valid approaches to this, too many to enumerate and consider here, but one obvious one is to do something like the property to be emulated while making it something else entirely.

The default play mode for Against the Darkmaster is precisely this, and, in my latest game, in which I am a player, we randomly and procedurally generated the “Darkmaster” – the Sauronic overlord who is to be opposed – his Lieutenants, his Minions, and his Spies. His Minions, it resulted, are Men, and right now I am playing Men characters who have “seen the Light” and hope to save other Men from their thralldom to the Darkmaster.

What, precisely, does it mean to faithfully emulate Tolkien’s works in an rpg? How, mechanically, should we express Tolkien’s Theory of Courage, the numinous quality of nature, eucatastrophe, Consolation and Recovery within the fantasy world, very high stakes, and – as Tolkien himself has stated – “a story without guarantees,” i.e., player characters without “plot armor?”

Well, one of my characters in the current game already has died, but nowhere near as heroically as did Boromir while attempting to protect the hobbits from capture. Nay, instead, while trying to hide from Evil Men, my character was eaten by alligators in a swamp.

HIs faith and mission to evangelize the Evil Men has been taken up by my other characters, though, and his recovered spear has become a relic – miraculously leafing and becoming the focal point of a shrine. The story never ends. It is forwarded by others, as Frodo says on the stairs of Cirith Ungol,

But the people in them come, and go when their part’s ended. Our part will end later – or sooner.

And the stakes are high. Combat is brutal and realistic. My characters have had to decide between trying to share the gospel of the Light with a Man who is likely an enemy or stabbing him in the back, knowing that the Evil Man would do the same to my characters should he know my characters’ allegiance with the Light. And this Evil Man will know that, should I share my character’s faith in an attempt to turn him. Do I risk it, or should I stab him in the back, and minimize threat to my characters? It is the Theory of Courage in a roleplaying game. How precious is my character? Try a spatula. Should I attempt the right thing, even if it almost certainly means death? But sometimes the dice reveal unexpectedly beneficial results. Not even the very wise can see all ends. Or inaccurately predict all probabilities. And, just when I am certain that my character is going to go down under the stamping feet of the Darkmaster’s hordes, the clouds may part upon white shores, and beyond, a far green country under a swift sunrise.

Prior Talking Tolkien entries:

Talking Tolkien – A New series at Black Gate!

Joe Bonadonna – Religious Themes in The Lord of the Rings

Ruth de Jauregui – The Architects of Modern Fantasy, Tolkien and Norton

Fletcher Vredenburgh – Of Such a Sort Should a Man Be – Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary

Anglachel – Tolkien’s Evil Magic Sword

David Ian – A Magical Tolkien Celebration

These days Gabe Dybing spends most of his time immersed in roleplaying games. The last time he wrote about Tolkien for Black Gate was in what he believes has been his most profound contribution to Tolkien criticism, “The Lost Literature of J.R.R. Tolkien’s ‘The New Shadow.’”

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE DEFINITIVE guide to Conan. He also organized 2024’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, ans XXXIII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

I guess there are arguments for and against the Covenant sequence? I’ve heard one argument – by somebody who was Presbyterian himself – that Donaldson’s Presbyterian background was a key factor in the creation of Covenant; that guilt is a central driving force in the character and that for Covenant to feel guilt, he has to have done something wrong. That said, my brother is re-reading the series again and says that Covenant’s sense of guilt about raping Elena is barely touched on.

This is all by way of qualification. You say that ‘…the entire soul of Tolkien’s masterpieces are subverted by a central figure who is an agnostic, misanthropic, and sociopathic anti-hero.’ But isn’t that the essence of the books’ appeal and what makes them original? The idea of a very real, flawed human being arriving in a middle-earth-type world and inhabited by very Middle Earth-type characters? Specifically how Covenant interacts with these characters? (e.g. his relationship with Foamfollower is a particularly good example).

I have long thought that Thomas Covenant was the most psychologically “true” portal fantasy protagonist, as his rejection of The Land, a place where his leprosy is miraculously healing and its signature disfigurement is taken as a sign of his heroic grandeur (“Berek Half-hand”), is a mental tactic to avoid falling into psychosis. Of course, I also thought his guilt over Elena’s rape that resulted from his “Unbelief” was his major motivation in trying to become something of a hero to absolve him of his sin. But it has been decades, so maybe a little guilt went a long way in 1970s fantasy literature.

‘But it has been decades, so maybe a little guilt went a long way in 1970s fantasy literature.’

Very true, Eugene. Coloured – in my case – by how I read the books as they came out and haven’t read them since.

Aonghus,

The one that really shook me was the 4th volume, The Wounded Land, as I have never seen a creator so thoroughly *assassinate* their creation. No wonder the Land’s suffering is termed “the Desecration”.

As I have (often) confessed, my sole reason for reading The Lord of the Rings was to better learn the background of Dungeons and Dragons (white box edition). And bless the Professor for putting “A Note Concerning Hobbits” as a prologue, thus obviating the need for my 16-year-old self to read The Hobbit first, as it would have put me off all Middle-earth as clearly 1,000 pages of “kiddie lit”, anathema to a (barely maturing) teen. Afterwards, yes, I did go back to The Hobbit and ahead to The Silmarillion, which was just being published.

And I will join you, Mr. Dybing, in enjoying The Fellowship the most, out of all 3 parts of LotR, though I do reserve a lot of affection for the scene in The Two Towers where Sam resists falling for the Ring’s temptation to become the Gardener of Mordor, an exquisite insight into how the Ring corrupts its bearers with good intentions.

I read the original Covenant trilogy several years back and found it a rough go, as I think Donaldson wanted it to be; I think putting his readers through it was part of his purpose. I don’t love the work but I do respect it, and I’ll probably revisit it some day. One thing I thought was ingenious and well-employed was the time gap between each of Covenant’s visits to the Land, so he could see the long-term consequences of his actions.

I never played any Middle-earth rpg’s but I did give the old SPI War of the Ring several go-rounds. I still have my Designer’s Edition (mounted maps – very nice).

Fascinating post, Mr. Dybing. I have the pleasure of owning MERP/RoleMaster and most of ICE’s Middle Earth supplements; the artwork and maps make reading them a real joy. Mr. Fenlon’s maps are superb and that map you have framed is literally a work of art. I’ve not read either The One Ring or Against the Darkmaster; maybe I need to change that.

Your comment regarding Shannara and the Covenant books “the former I found to be without substance, the latter I found to be odious.” Precisely.

Thank you again for your post!

I read the Covenant books (the first two trilogies) multiple times in high school & college. Last time I reread them (about 15-20 years ago, when the first book in the new sequence came out), I recognized their flaws but still was amazed at how many elements from them I had internalized into my personal fantasy lexicon.

As for MERP, I never played it (or, to be fair, pretty much of anything) but I owned the original red rulebook and a few of the supplements, and I appreciated them but honestly, Middle Earth seems like a setting that really doesn’t work unless you’re essentially recapitulating LotR (or some kind of close analogue) even if you are using a time hundreds of years before the books or whatever.

I always thought Terry Brooks was a terrible writer with all sorts of plot holes. One homage to Tolkien I liked was the Iron Tower trilogy by Dennis L. McKiernan.

‘Sword of Shannara’ is my favorite fantasy novel, so we differ on that. 🙂

But Dennis L. McKiernan’s Mithgar is as true a successor to Tolkien as we’ll get. In fact, The Silver Call Duology was actually written as a sequel to the Moria story. The Tolkien people told him NOPE. A publisher told him to write a LotR-like trilogy of his own creation. He did so – The Iron Tower Trilogy – it was published, and The Silver Call followed, retrofit to MIthgar.

He used to live here in central Ohio. Way back when, I looked up his phone number in the book and called him. He invited me out. I brought several books which he signed, and we talked fantasy authors, and his RPG of choice (he was into the ICE system, not D&D). Just a super nice guy. He moved out to Arizona some years later, where he still is.

McKiernan’s stats for his Rolemaster game are available on a Geocities site. But it is SO FULL of raunchy ads, when I went looking right now, that there is no way I’m going to link it! 😀

:-):-) 🙂

[…] (Black Gate): I have decided to take “Discovering Tolkien,” the title of this series, as my means of entry […]