Talking Tolkien: Of Such a Sort Should a Man Be – Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary by J.R.R. Tolkien – by Fletcher Vredenburgh

Talking Tolkien is back for another installment and Black Gate’s own Fletcher Vredenburgh looks into the Professor’s delve into one of the classics of English literature: Beowulf. Read on! For all those who wander are not lost.

Talking Tolkien is back for another installment and Black Gate’s own Fletcher Vredenburgh looks into the Professor’s delve into one of the classics of English literature: Beowulf. Read on! For all those who wander are not lost.

Of Such a Sort Should a Man Be: Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary by J.R.R. Tolkien

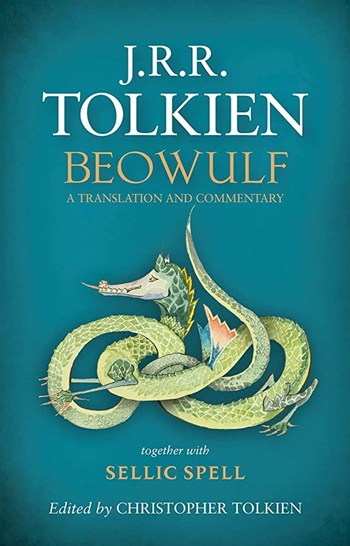

This is a book that shouldn’t exist. Prof. Tolkien began his translation of the Old English poem in 1920 and worked on it until 1926. It’s posited his move from the University of Leeds to Oxford and his commencement of The Hobbit prevented him from devoting more time to the translation. Ultimately, he undertook the effort for himself and was never satisfied enough with it to have it published. As with nearly everything else he left unfinished or unpolished, his son Christopher published it. In 2014 it appeared, collected with commentary on the poem Tolkien had prepared for and several Beowulf-inspired works.

For those unfamiliar with Beowulf, it is an epic poem in the West Saxon dialect of Old English. It is believed to have been composed between 975 AD and 1025 AD. It concerns events taking place in Scandinavia during the 6th century. The first half describes the ravaging of the King Hrothgar of Denmark’s great hall Heorot by the monster Grendel, and Beowulf’s effort to kill him (and the monster’s mother). The second half tells of Beowulf’s ill-fated battle in his old age against a dragon. Interspersed throughout the poem are tales of the fates of various kings and warrior during a period of constant raiding and war among the kingdoms around the Baltic Sea. Debate exists over whether it was originally composed during pagan time or Christian times.

Unlike literary versions such as Seamus Heaney’s popular version from 1999, Tolkien’s aimed for greater linguistic and grammatical fidelity. His translation is prose, not poetic, which another Beowulf-translator described as sticking “as closely as possible to the meaning and clause-order of the original. It has great accuracy and a sense of rhythm. Its style is, like that of the original, archaic, and often has striking inversions of word-order.”

This does make it more difficult reading than Heaney’s or many of the other translations, but I found it captivating as it dragged me backwards in time on the power of Tolkien’s chosen words.

J.R.R. Tolkien translation

He came now from the moor under misty fells, Grendel walking. The wrath of God was on him. Foul thief, he purposed of the race of men someone to snare within that lofty hall.

Original Old English (W.Saxon)

Ða com of more under misthleoþum

Grendel gongan, Godes yrre bær.

Mynte, se manscaða manna cynnes,

sumne besyrwan in sele þam hean.

Tolkien was also intent on getting at what he saw as the artistic and mythic heart of the poem. In his 1936 lecture, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics,” he said the poem is essentially about a “man at war with the hostile world, and his inevitable overthrow in Time.” He also felt that too many previous scholars had dismissed the fantastic elements of Beowulf, instead focusing on the historical elements. Their goal was to uncover what real life was like in the Saxon period of the poems composition and the earlier Germanic cultures of the Baltic region. Tolkien likened them to people who upon discovering some of the stones of a tower were older than the tower, tore it down in order to “to look for hidden carvings and inscriptions.” If the poet possessed a mind “lofty and thoughtful,” as Tolkien clearly believed, he would only have written so many lines about such things if they were important.

Tolkien was also intent on getting at what he saw as the artistic and mythic heart of the poem. In his 1936 lecture, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics,” he said the poem is essentially about a “man at war with the hostile world, and his inevitable overthrow in Time.” He also felt that too many previous scholars had dismissed the fantastic elements of Beowulf, instead focusing on the historical elements. Their goal was to uncover what real life was like in the Saxon period of the poems composition and the earlier Germanic cultures of the Baltic region. Tolkien likened them to people who upon discovering some of the stones of a tower were older than the tower, tore it down in order to “to look for hidden carvings and inscriptions.” If the poet possessed a mind “lofty and thoughtful,” as Tolkien clearly believed, he would only have written so many lines about such things if they were important.

J.R.R. Tolkien translation

Now was the day faded to the serpent’s joy. No longer would he tarry on the mountain-side, but went blazing forth, sped with fire. Terrible for people in that land was the beginning (of that war), even as swift and bitter came its end upon their lord and patron. Now the invader did being to spew forth glowing fires and set ablaze the shining halls – the light of the burning leapt forth to the woe of men. No creature there did that fell winger of the air purpose to leave alive.

Original Old English (W.Saxon)

Þa wæs dæg sceacen >

wyrme on willan. No on wealle læg

bidan wolde, ac mid bæle for,

fyre gefysed. Wæs se fruma egeslic

leodum on lande, swa hyt lungre wearð

on hyra sincgifan sare geendod.

ÐA se gæst ongan gledum spiwan,

beorht hofu bærnan. Bryneleoma stod

eldum on andan. No ðær aht cwices

lað lyftfloga læfan wolde.

I read in Beowulf, the twofold story of a hero; his earliest deeds that bring him to prominence and his final actions that bring his end. There are many bold and mighty warriors mentioned throughout the poem, but most of their acts are performed in the middle of one war or feud or another. Beowulf arrives at Hrothgar’s hall in order to “redeem it from the malice of Grendel.” He acts from nobility and goodness as much as pride in his skills and bravery. By the killing of Grendel and his mother he has become the man he presumed himself to be. We read how, by his loyalty and honor to his, he remains across his long life the sort of man a man should be. When his final days come and the dragon ravages his realm, he willingly straps on his sword one last time and strides forth. He alone possesses the courage and the strength to battle and defeat the serpent.

J.R.R. Tolkien translation

Wait now on the hill, clad in your corslets, ye knights in harness, to see which of us two may better endure his wounds when the combat is over. This is not an errand for you, nor is it within the measure of any man save me alone that he should put forth his might against the fierce destroyer, doing deeds of knighthood. I shall with my valour win the gold, or else shall war, cruel and deadly evil, take your prince.

Wait now on the hill, clad in your corslets, ye knights in harness, to see which of us two may better endure his wounds when the combat is over. This is not an errand for you, nor is it within the measure of any man save me alone that he should put forth his might against the fierce destroyer, doing deeds of knighthood. I shall with my valour win the gold, or else shall war, cruel and deadly evil, take your prince.

Original Old English (W.Saxon) >

Gebide ge on beorge byrnum werede,

secgas on searwum, hwæðer sel mæge

>æfter wælræse wunde gedygan

uncer twega. Nis þæt eower sið,

ne gemet mannes, nefne min anes.

>Wat he wið aglæcean eofoðo dæle,

eorlscype efne. “Ic mid elne sceall

gold gegangan, oððe guð nimeð,

feorhbealu frecne frean eowerne.”

The greatest portion of the book is made up of commentary by Tolkien on his translation. These are probably the most valuable thing for a reader of Beowulf. Some are straightforward explanations of the technical aspects of his methods. The most striking is his demolition of the translation of the word >hronrad as “whale road.” It’s a long, complex explanation but it seems very strong.

Of even greater value in the commentary are Tolkien’s larger opinions on the poem. The first is that he saw it as an amalgam of history and fairy tale. He also explores this in the Sellic Spell (Marvellous Tale), a fairy tale Tolkien wrote retelling the first portion of Beowulf as a folkloric story and which is included in the book.

The second is his evidence for Beowulf as the work of a Christian writer. Not only are their assorted hallmarks of the author’s Christianity in the text, Tolkien also believed part of his intent was to account for the virtuous deeds of pagan heroes. While portrayed as a pagan, Beowulf and other noble characters are aware of the power of the Christian God in ordering the universe.

The second is his evidence for Beowulf as the work of a Christian writer. Not only are their assorted hallmarks of the author’s Christianity in the text, Tolkien also believed part of his intent was to account for the virtuous deeds of pagan heroes. While portrayed as a pagan, Beowulf and other noble characters are aware of the power of the Christian God in ordering the universe.

“>But the author of Beowulf was writing for a society in which Christianity had not long been established, a few generations perhaps, but kings and nobles knew and honoured the names of their pagan ancestors, not so far back.

Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary concludes with two versions of a poem by Tolkien, “The Lay of Beowulf.” The first version, Christopher Tolkien points out, was sung to him by his father when he was a young boy.

Having read relatively recently (and written about here at Black Gate) Howell Chickering’s translation, I was able to follow Tolkien’s translation. I suspect it might be a little difficult for someone new to Beowulf. Nonetheless, it is worth any effort one might need. The real prize, though, is the extensive commentary. Most people, myself included, only know Tolkien from his fiction, not his academic work and this serves as a good and accessible introduction. This is the third translation of Beowulf I have on my shelves, now, and for that I’m very grateful to Christopher Tolkien and, of course, his father.

Prior Talking Tolkien entries:

Talking Tolkien – A New series at Black Gate!

Joe Bonadonna – Religious Themes in The Lord of the Rings

Ruth de Jauregui – The Architects of Modern Fantasy, Tolkien and Norton

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column the first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE DEFINITIVE guide to Conan. He also organized 2024’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, ans XXXIII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

Most excellent, Fletcher!

Thank you

The second half of Beowulf is more tragic (the death of the hero) than heroic, which is why it always speaks louder to me, that notion that there is no retirement for the hero other than the permanent exit of the grave. It is tied to an idea of sacrifice, too, which is a possible connection to the Christian Gospel sacrifice narrative. So that may be another reason it reads so strongly to me, having been taught the figure of the sacrificial savior.

Good insights, both

Great stuff! Thanks for the thoughtful review.

I love this book, more for the commentary than the translation. It’s almost impossible to overstate the importance Tolkien had for transforming the interpretation of Beowulf in the last century. It’s fun to see him engaging with the poem on every level: chewing on individual words with a philologist’s dusty glee; listening to therhthym of the lines with a poet’s ear; seeing the long arcs of tragedy and heroic sacrifice with storyteller’s eye.

Thank you. The commentary is what I should have written about most, but I’ve got to admit I felt a little daunted.

I remember reading Beowulf when I was supposed to be studying Spanish. I was never very good with Spanish. That the poem really spoke to me. It is certainly more than a work important for its place in history. It is a living story.

Absolutely.

Thank you. It has been a very long time since I read Beowulf (my old copy is long gone). Perhaps I need to change that, and this version sounds like an excellent choice.