Ellsworth’s Cinema of Swords: Samurai with a Twist

Samurai Spy (Japan, 1965)

By the 1960s, the tropes of chambara films, i.e., samurai adventures, had become through endless repetition standardized and over-familiar. As with the Western film in America and Europe, it was time for variations on the theme less they lose their audience, and so antiheroes raised their unfeeling heads and genre crossovers appeared, such as the samurai-meet-kaiju Daimajin movies. This week we take a look at a couple of interesting antihero adventures plus a crossover with the then-popular secret agent genre, Samurai Spy. Let’s dive in!

Destiny’s Son (or Kiru)

Rating: ***

Origin: Japan, 1962

Director: Kenji Misumi

Source: YouTube streaming video

This is a curiosity, an artsy, almost experimental chambara film from Kenji Misumi, a director best known for his contributions to the Zatoichi and Lone Wolf and Cub series. The story firmly identifies itself as a tragedy from the beginning, when a young samurai woman of the Iida murders her lord’s wicked concubine “for the good of the clan.” She’s arrested and condemned, but her infant son is sent away to be raised in the Komoro clan. Twenty years later, handsome Shingo (Raizô Ichikawa), unaware that he’s adopted, asks permission to leave Komoro and travel about “a little bit everywhere” for three years.

He returns with an air of romantic melancholy and a new fencing style he’s invented, a “shamisen stance” so threatening that even experienced swordsmen, when faced with it, begin to tremble and then admit defeat. In a tournament, this stance enables Shingo to defeat a powerful challenger and protect the Komoro clan’s honor, but it also earns him the enmity of jealous rivals, who kill his foster family. In a dying revelation, Shingo’s adoptive father tells him of his real origins in the Iida clan. The young man sets out to find the truth of his background, learning in the process that life is both wonderful and cruel.

Only slightly longer than 70 minutes, with a story told almost in shorthand and with abrupt changes of scene, Destiny’s Son often sacrifices coherence for poetic impressionism, every sequence ending in some dark outbreak of violence. (Using his samishen stance, Shingo kills one ambusher with a flowering branch.) Many of these scenes are striking and memorable, but the characters are mostly archetypes with little space for development. Even Shingo only gets more romantically melancholy with time, drifting into reveries of three women whose lives he couldn’t save, his mother, his sister, and an unnamed, fierce fugitive who died fighting (in the nude, for extra art points) so her brother could escape their pursuers.

The story slides into the Bakumatsu, the period of civil strife at the end of the Shogunate, and Shingo is inevitably caught up in politics, but dreaming of his three lost ladies he pays little attention until the lord he is sworn to protect is assassinated on his watch. “There is no excuse,” he tells himself, as he prepares for his inevitable end.

Right, fair enough: we’ve known all along that Shingo’s tale is about finding beauty in the face of implacable fate and suchlike, so you have no one to blame but yourself if you’re looking for an incongruously happy ending. Enjoy it for what it is anyway.

The Secret Sword (or Hiken)

Rating: *****

Origin: Japan, 1963

Director: Hiroshi Inagaki

Source: Samurai DVD

The secret thrust is a common trope in swashbuckling literature, an attack that, under certain conditions, is unbeatable and cannot be parried, and is usually passed down as the final lesson between master and student, father and son. The idea of the secret sword thrust occurs in all fencing traditions, including, of course, Japan’s.

Director Hiroshi Inagaki is best known to Americans and Europeans for lush historical epics such as the Samurai trilogy and Chushingura (1962). After completing the latter, Inagaki cleansed his palate with this intimate and intense chambara character study, shot in moody black and white like a film noir. Like Okamoto’s Sword of Doom (1966), it follows the descent of a dedicated swordsman into cruelty and obsession as he loses his humanity to his devotion to the sword.

Based on a novel by Kosuke Gomi, the story is set in 1633, early in the Tokugawa shogunate, when peace has idled thousands of samurai warriors and at the same time made it illegal to fight matches with real blades. Young Tenzen (Koshiro Matsumoto), though a samurai of the lowest rank, is his clan’s most talented swordsman and is determined to become a famous practitioner of the martial arts, though he’s allowed to practice only with wooden or bamboo weapons. An orphan, Tenzen was raised in the house of Chojuro (Hiroyuki Nagato), who considers him a brother, and his talent has already won for Tenzen an engagement with a higher-ranking daughter of the clan. But someone among the young samurai has been murdering untouchables, lowly street workers, with a sword, and when the clan inspector decides Tenzen should take the blame and accept a nominal punishment to cover it up on the clan’s behalf, Tenzen angrily refuses because the untouchables were clumsily slaughtered rather than cleanly slain.

About this time famous duelist Musashi Miyamoto (Ryunosuke Tskukigata), now a retired sage, comes to the clan to visit an old friend, and is confronted by the clan’s young firebrands, who demand that Musashi support their sword-wielding ambitions. Musashi chides them for the murders of the untouchables, saying the Way of the Sword is not about killing, it’s the way of all arts, and then whips up a heavy floor mat and bisects it vertically with a single blow of his sword. Tenzen, unimpressed, calls it a stunt and does the same trick — horizontally, which seems even more impressive.

But Tenzen has now shamed his clan: his engagement is broken off and he’s confined to his quarters in house arrest for 100 days. He escapes to visit and upbraid his former fiancée, and when he’s caught by clan enforcers, he cuts them down and flees. His stepbrother, Chojuro, is charged with bringing him back to commit suicide, or Chojuro must commit seppuku in his place.

The character of Chojuro, fearful but determined, now comes to the fore as he searches for Tenzen, who has found refuge in the mountains. Obsessed, Tenzen practices alone in the woods every day until he invents a secret sword thrust that defeats an opponent by severing their thumb behind the sword guard. Chojuro finds him, but instead of killing or capturing Tenzen, he joins him, and his stepbrother teaches him his secret thrust. But the clan has not relied solely on Chojuro to bring Tenzen in, and when a squad of samurai track him down, Tenzen kills or cripples them all and then flees again.

Chojuro visits Musashi to ask for advice on how Tenzen can be redeemed and his talent saved for the clan, but Musashi tells him he cannot, as the secret thrust is an abomination: “The sword is not used merely for winning — it is a mirror that reflects the soul.” And so, the stage is set for a tense confrontation between the stepbrothers amid the bizarre lava-forms on the slopes of an active volcano.

This superb film is hard to find in a version with English subtitles, but you won’t regret the trouble it takes to track it down.

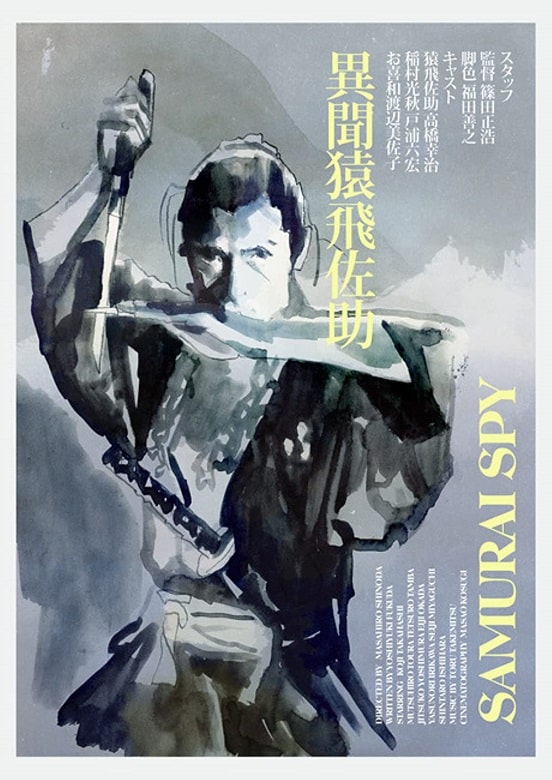

Samurai Spy (or Spy Hunter)

Rating: ****

Origin: Japan, 1965

Director: Masahiro Shinoda

Source: Criterion DVD

1965 was a big year for spies and secret agents, so why not make a samurai spy movie? This has all the hallmarks of the spy genre: mirror-image espionage agencies locked in a cynical dance of deceit, double agents selling out to both sides, mysterious women who fall into the hero’s arms, a secret mastermind pulling the strings behind the murders and betrayals, and a spy hero who’s had enough of the soul-crushing game and just wants out. Samurai Spy is a darling of the serious critics because it’s artsy and dark and poses a critique of society’s culture of hypocrisy, but what the serious critics don’t mention is that it’s also some goofy fun, I’m here to tell you.

In 1600 the Battle of Sekigahara ended the era of warring states with a victory for the Tokugawa clan, but the defeated Toyotomi continued a shadow war to try to recover their power and influence. Under a façade of peace, the covert espionage clans of the Tokugawa and the Toyotomi conduct a war of spies, while neutral clans such as the Sanada and Suwa try to increase their leverage by dealing with both sides. The samurai Sasuke (Koji Takahashi) is a top spy for the Sanada who’s growing sick of the eternal conflict, the cruelty, betrayal, and death, but when Tokugawa spy chief Tatewaki (Eiji Okada) disappears in an apparent defection, Sasuke gets caught up in the pursuit because everyone thinks he knows where Tatewaki has gone.

Events go over the top immediately, and about all you can do is enjoy the ride. There are throwing stars and hooked chains, assassins in animal masks, a hallucinogenic episode, a clan of crypto-Christians, and an unexplained recurring beggar boy who walks through scenes dragging a dead raven. Best of all is the depiction of the other Tokugawa spy chief, Sakon (Tetsuro Tamba), a sort of ninja-in-white who appears and disappears and fights in a theatrical two-sword style. Sakon’s spy clan is the Yagyu, who were the original ninja, so there are lots of early ninja tropes and even proto-kung fu high leaps in slo-mo. It’s a hoot.

All of the above is not to diminish the artistry of director Masahiro Shinoda, who has an eye for composition that compares with Kurosawa’s, and who stages combats with a bracing mix of long shots and close-ups in gorgeous natural environments that almost upstage the swordplay. The story is complicated, a five-sided treachery-fest, but if you lose track of who’s who, it’s still a rich visual feast. However, if you pay attention, it hangs together and you can follow it, reversal after reversal, all the way to the end when it finally makes sense. (Except for the beggar boy with the raven: what’s up with that?)

Where can I watch these movies? I’m glad you asked! Many movies and TV shows are available on disk in DVD or Blu-ray formats, but nowadays we live in a new world of streaming services, more every month it seems. However, it can be hard to find what content will stream in your location, since the market is evolving and global services are a patchwork quilt of rights and availability. I recommend JustWatch.com, a search engine that scans streaming services to find the title of your choice. Give it a try. And if you have a better alternative, let us know.

Previous installments in the Cinema of Swords include:

Swashbucklin’ Talkies

Barbarian Boom Part 6

Valiant Avenging Chivalry

Buccaneers Three

For the Horde!

The Princess Bride Redeems the 80s

Samurai Stocking Stuffers

Moonraker! (No, Not That One)

Cinema of Swords Book Announcement!

Fury of the Norsemen

LAWRENCE ELLSWORTH is deep in his current mega-project, editing and translating new, contemporary English editions of all the works in Alexandre Dumas’s Musketeers Cycle; the sixth volume, Court of Daggers, is available now as an ebook or trade paperback from Amazon, while the seventh, Devil’s Dance, is being published in weekly installments at musketeerscycle.substack.com. His website is Swashbucklingadventure.net. Check them out!

Ellsworth’s secret identity is game designer LAWRENCE SCHICK, who’s been designing role-playing games since the 1970s. He now lives in Dublin, Ireland, where he’s a Narrative Design Expert for Larian Studios, writing Dungeons & Dragons scenarios for Baldur’s Gate 3.

Another Ellsworth’s Cinema of Swords? More Samurai!

Once again, you have found three fascinating films that I’ve never even heard of! All of them look interesting to me and I’ll have to try to find them.

Thanks again!