Might For Right: The Once and Future King, Part 1 by T.H. White

“I have been thinking,” said Arthur, “about Might and Right. I don’t think things ought to be done because you are able to do them. I think they should be done because you ought to do them.”

King Arthur, p. 239 The Once and Future King

I first read English author T.H. White’s The Once and Future King when I was seventeen, fresh from seeing the movie Camelot (1967) for the first time (the musical Camelot, by Lerner and Lowe was based on parts of White’s novel). The tale of Arthur Pendragon, by turns both comic and tragic, told in a thoroughly anachronistic and post-modern way, reached me as few other books had. The story of Arthur’s education and effort to create a better world and his ultimate failure and downfall broke my heart. I absolutely loved the book and used it as the basis for my AP English exam essay instead of any of the books I’d read in class (I aced the test). More than any other Arthurian book or movie, White’s book forms my image of Arthur’s doomed noble reign.

I know I reread the book once during college or grad school, but that was over thirty years ago and my memories are dim. To say I approached The Once and Future King last month with some trepidation is an understatement. There’s been more than one greatly admired book I’ve revisited only to find out that whatever affection I held for it had flown. I did not want that to happen here. Nonetheless, spurred again by watching Camelot recently, I was determined to read the book. Having finished the first two parts of the novel, I am happy to find that not only do I still love the book, I’m impressed more than ever by its power and White’s artistry. Note: To convey the latter point, I’ll be quoting the book generously.

The Once and Future King is really four books; The Sword in the Stone (1938), The Witch in the Wood, later retitled The Queen of Air and Darkness (1939), The Ill-Made Knight (1940), and The Candle in the Wind (1958). The first three were all published as standalone novels, the fourth only as part of the unified four-book collection. A fifth part, The Book of Merlyn (1977), was written in 1941 but wasn’t published until long after White’s death in 1964. For today, I’m going to write on the first two parts.

The Sword in the Stone draws largely on Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur (ca. 1470), detailed with White’s own extensive knowledge of jousting, falconry, and hunting. Presented as a children’s book, it tells the story of Wart, the adopted son of Sir Ector of the Castle Sauvage. White’s Arthur is a post-Conquest Norman in a story-book version of 14th-century Britain filled with bits and pieces of British legend and littered signs and portents. It’s also the basis for Disney’s 1963 movie of the same name.

The Wart watched his arrow go up…Up and Up it went, not weaving as it would have done with a snatching loose, but soaring, swimming, aspiring to heaven, steady, golden and superb. Just as it had spent its force, just as its ambition had been dimmed by destiny and it was preparing to faint, to turn over, to pour back into the bosom of its mother earth, a portent happened. A gore-crow came flapping wearily before the approaching night. It came, it did not waver, it took the arrow. It flew away, heavy and hoisting, with the arrow in its beak.

Kay was frightened by this, but the Wart was furious. He had loved his arrow’s movement, its burning ambition in the sunlight, and, besides, it was his best one. It was the only one perfectly balanced, sharp, tight-feathered, clean-nocked, and neither warped nor scraped.

“It was a witch,” said Kay.

At one point, Arthur and his foster brother, Kay, undertake a rescue mission into Morgan le Fay’s castle, accompanied by Robin Hood, Maid Marian, and the rest of the Merry Men. Hood and his band are portrayed as Saxon rebels against the Norman king, Uther Pendragon. Given his own chance for adventure, Kay slays a griffin and brings its head home for Sir Ector to mount. It’s a wonderful concoction that makes no apologies whatsoever for chucking any sort of historicity right out the window.

While hunting one day, Wart becomes separated from Kay and proceeds to get lost in the Forest Sauvage. There, he unexpectedly comes across a cottage and a strange old man “dressed in a flowing gown…embroidered with the signs of the zodiac” and all other sorts of magical symbols.

The aged gentleman put down his bucket and looked at him.

“Your name would be Wart.”

“Yes, sir, please, sir.”

“My name,” said the old man, “is Merlyn.”

Merlyn and his talking owl Archimedes accompany Wart back to the castle where the magician quickly convinces Sir Ector to hire him to tutor Wart and Kay. While he gives both boys a general education, he gives Wart a special one that involves turning him into different types of animals to experience different facets of the world through different eyes. He is unknowingly being prepared and given the insights and mental tools he will need for the future.

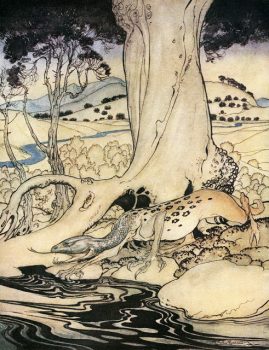

First, Wart becomes a fish swimming in the castle’s moat. There he meets the King of the Moat, Mr. P., a great pike with a face “ravaged by all the passions of an absolute monarch — by cruelty, sorrow, age, pride, selfishness, loneliness and thoughts too strong for individual brains.”

When Wart tells Mr. P he doesn’t know what to ask him, the predator replies:

“There is nothing,” said the monarch, “except power which you pretend to seek: power to grind and power to digest, power to seek and power to find, power to await and power to claim, all power and pitilessness springing from the nape of the neck.”

“Thank you.”

“Love is a trick played on us by the forces of evolution. Pleasure is the bait laid down by the same. There is only power. Power is of the individual mind, but the mind’s power is not enough. Power of body decides everything in the end, and only Might is Right.”

Later he is transformed into an ant to experience the terrors of absolute authoritarianism and endless war, and a goose to experience freedom from borders. Without ever being told why, Wart is taught how a world where Might is Right works and how to begin imagining a way out of it.

The actual sword in the stone doesn’t make an appearance until the last few chapters of the book after Uther has died. We first read about it in a conversation worthy of Abbot and Costello.

“Do you mean to tell me,” exclaimed Sir Grummore indignantly, “that there ain’t no King of Gramarye?”

“Not a scrap of one,” cried King Pellinore, feeling important. “And there have been signs and wonders of no mean might.”

“I think it’s a scandal,” said Sir Grummore. “God knows what the dear old country is comin’ to. Due to these lollards and communists, no doubt.”

“What sort of signs and wonder?” asked Sir Ector.

“Well, there has appeared a sort of sword in a stone, what, in a sort of church. Not in the church, if you see what I mean, and not in the stone, but that sort of thing, what, like you might say.”

“I don’t know what the Church is coming to,” said Sir Grummore.

“It’s an anvil,” explained the King.

“The Church?”

“No, the sword.”

“But I thought you said the sword was in the stone?”

“No,” said King Pellinore. “The stone is outside the church.”

“Look here, Pellinore,” said Sir Ector. “You have a bit of a rest, old boy, and start again. Here, drink up this horn of mead and take it easy.”

“The sword,” said King Pellinore, “is stuck through an anvil which stands on a stone. The stone stands outside a church. Give me some more mead.”

Written on the sword in letters of gold are the words:

Whoso Pulleth Out This Sword of this Stone and Anvil, is Rightwise King Born of All England

On an errand to retrieve Kay’s forgotten sword, Wart, of course, pulls the sword from the stone. Starved for order and “sick of the anarchy which had been their portion under Uther Pendragon,” most of the people of Britain willingly accept Wart, now King Arthur. It is only after that, that Merlyn tells Wart that he is Uther’s son and how disguised as a beggar, Merlyn brought the infant Wart to Sir Ector.

The Queen of Air and Darkness, a line from an A.E Housman poem, refers to Morgause of Cornwall, wife of King Lot of Orkney and half-sister of Arthur. She is a mother with little interest in her sons, a wife with little affection for her husband, and a witch of little constancy. The only things that drive her are boredom and a desire for vengeance against the Pendragon family. The latter proves so strong that in the end, she employs black magic to ensnare her half-brother Arthur, rape him, and give birth to Mordred. It is by their son that she will destroy her half-brother and all that he loves.

The book opens with her four sons, Gawaine, Agravaine, Gaheris, and Gareth, recounting the story of Uther’s killing of their grandfather and how he forced himself on their grandmother, Igraine. The crimes behind Arthur’s engendering will lead, more than anything else, to the destruction of the king and his realm.

“And this, my heroes,” concluded Gawaine, “is the reason why we of Cornwall and Orkney must be against the Kings of England ever more, and most of all against the clan Mac Pendragon.”

“It is why our Da has gone away to fight against King Arthur whatever, for Arthur is a Pendragon. Our Mammy said so.”

“And we must keep the feud living forever,” said Agravaine, “because Mammy is a Cornwall. Dame Igraine is our Granny.”

“We must avenge our family.”

“Because our Mammy is the most beautiful woman in the high-ridged, extensive, ponderous, pleasantly-turning world.”

“And because we love her.”

Indeed, they did love her. Perhaps we all give the best of our hearts uncritically — to those who hardly think about us in return.

Their unbearable desire for any show of affection from Morgause and lack of any education beyond that provided by the violence-inclined St. Toirdealbhach leaves the boys prone to fits of jealousy and rage. It leads the boys to undertake an ultimately terrible and bloody quest for a unicorn. It’s a dark parallel to Kay’s and Wart’s battle with the griffin. This hunt brings nothing but tragedy and a whipping for the boys from their mother. The whipping is not for the crime of killing such a noble beast, but because she hadn’t been able to catch one herself.

The Orkneys are presented in as brazenly an ahistorical manner as England is, albeit with a marvelously overdone Celticness. Saints aplenty live in beehive cells, everyone speaks with a thick burr (except when they don’t), and the smell of burning peat permeates the air. When Morgause and her sons decamp for England the whole mythic countryside rises up to bid them farewell.

All the saints came out of their beehives to see them off. All the Fomorians, Fir Bolg, Tuatha de Danaan, Old People and others waved to them without the least suspicion from cliffs, currachs, mountains, bogs and shell-mounds. All the red deer and unicorns lined the high tops to bid good-bye. The terns came with their forked tails from the estuary, squeaking as if intent upon imitating an embarkation scene on the wireless — the white-bottomed wheaters and pipits flitted along beside them from whin to whin — the eagles, peregrines, ravens and chuffs made circles over them in the air — the peat smoke followed them as if anxious to make one last curl in the tips of their nostrils — the ogham stones and souterrains and promontory forts exhibited their prehistoric masonry in a blaze of sunlight — the sea-trout and salmon put their gleaming heads out of the water — the glens, mountains and heather-shoulders of the most beautiful country in the world joined the general chorus — and the soul of the Gaelic world said to the boys in the loudest of fairy voices: Remember Us!

At the same time as the events in the Orkneys, newly-crowned King Arthur is under assault by a great army of rebel barons under the command of King Lot. While awaiting the great confrontation the war has been building towards, Arthur begins to imagine a way out of the current violent and anarchic age. It begins when he expresses to Merlyn that a battle he’d just fought was fun and the wizard asks him how many foot soldiers were killed versus how many knights.

Merlyn refuses to give any advice to Arthur when asked what to do. Instead, he forces Arthur to think for himself, drawing on what he’s learned and his own innate goodness. This leads to the declaration in the lines quoted above: Might for Right. The next question, then, is how to implement such a novel idea. And so he comes up with a novel solution: an order of chivalry dedicated to only striking on “behalf of what is good, to defend virgins…and to restore what has been done wrong in the past and help the oppressed and so forth.” So that no knight will be able to claim pre-eminence by sitting at the head of it, he’ll get a round one.

The Once and Future King has a reputation as a pacifist work, which I think is an incorrect interpretation. White was by nature a pacifist, but, to many of his friends’ shock, he attempted to enlist during the Second World War. For him, it was easy to see Hitler as someone to be opposed at all costs. In several conversations between Arthur, Merlyn, and Kay, White makes the case for pacifism as well as multiple reasons for waging war, each character voicing opinions White held on the matter. Merlyn is the pacifist (though he will lead a portion of Arthur’s army). He insists man must simply break out of the cycle of violence and revenge, even when such actions seem justified. Arthur is the idealist, believing that sometimes there are enemies too awful to be allowed free reign. Finally, Kay is the realist. He is the one who points out that no matter what vision of a better world Arthur is seeking, it will require force and violence to impose that vision. It’s a deeply felt and thought-through debate that ultimately reaches no definitive conclusion.

Once Arthur has made his determination to pursue a new, more just order, he also determines how to bring the war with King Lot and his allies to an end. Instead of allowing the usual course of battle wherein heavily armored nobles slaughter the ranks of peasant spear carriers, he directs his own chivalry to attack by night and bear down heavily and exclusively on the enemy knights. While still a near-run thing, the great Battle of Bedegraine breaks the enemy coalition and cements Arthur’s rule over England. It’s also, despite White’s own conflicted thinking on violence, portrayed with unmistakable degrees of power, majesty, and appeal.

The charges began with the growing day.

At a military tattoo perhaps, or at some old piece of show-ground pageantry, you may have seen a cavalry charge. If so, you know that “seen” is not the word. It is heard — the thunder, earth-shake, drum-fire, of the bright and battering sandals! Yes, and even then it is only a cavalry charge you are thinking of, not a chivalry one. Imagine it now, with the horse twice as heavy as the soft-mouthed hunters of our midnight pageants, with the men themselves twice heavier on account of arms and shield. Add the cymbal-music of the clashing armour to the jingle of the harness. Turn the uniforms into mirrors, blazing with the sun, the lances into spears of steel. Now the spears dip, and now they’re coming. The earth quakes under feet. Behind, among the flying clods, there are hoof-prints stricken in the ground. It is not the men that are to be feared, not their swords nor even their spears, but the hoofs of the horses. It is the impetus of that shattering phalanx of iron — spread across the battlefront, inescapable, pulverizing, louder than drums, beating the earth.

In addition to these two more serious strands, there’s a third, comical one to The Queen of Air and Darkness. Brought to the Orkneys by a magical boat, King Pellinore, Sir Grummore, and Sir Palomides sojourn with Queen Morgause and her subjects. Pining for his lover, the daughter of the Queen of Flanders, Pellinore becomes a sad, abject man. Having also abandoned the Questing Beast, the object of his pursuit for years, Palomides and Grummore come up with a plan to distract the King from his romantic woes. It involves dressing up as the Questing Beast herself and it doesn’t end well for the knights and beast alike.

The three narratives are brought together in the last chapters when reunited, King Pellinore and the Queen of Flanders’ daughter, Piggy, travel to Carlion to meet King Arthur and be married. Simultaneously, Morgause, with her four boys in tow, journeys south from the Orkneys ostensibly to seek a pardon from Arthur for her husband. Her real motive as described above is to magically seduce her brother with a talisman made from a dead man’s skin.

The way to use a Spancel was this. You had to find the man you loved while he was asleep. Then you had to throw it over his head without waking him, and tie it in a bow. If he woke while you were doing this, he would be dead within the year. If he did not wake until the operation was over, he would be bound to fall in love with you.

And with this act, the entirety of The Once and Future King begins to move toward tragedy, even as King Arthur, his head filled with powerful new ideas, seems on the verge of complete triumph. In a somber concluding paragraph of The Queen of Air and Darkness, White reminds the reader that “Sir Thomas Malory called his very long book the Death of Arthur.” For White, Arthur’s story is one of “sin coming home to roost,” and even innocence is not enough to prevent his ruination.

And still, even though its arc is tragic, it’s a hopeful book. Despite White’s despair over humanity’s inability to relinquish its savage tendencies, he also clearly believed that it had the capacity to understand that and find ways to channel and repurpose them. Even in the face of rebellion and possible defeat, Arthur can envisage a land blessed with order and justice. That vision will prove in the next book to be a gloriously infectious one.

TOaFK is animated by a certain humanism and sympathy for our flaws. Throughout the book, there’s an appreciation of the fallibility of humans (a theme that takes over much of The Ill-Made Knight and the story of Lancelot). This is made clear in a scene where Merlyn is exceedingly harsh toward Kay.

“Kay,” said Merlyn, suddenly terrible, “thou wast ever a proud and ill-tongued speaker, and a misfortunate one. Thy sorrow will come from thine own mouth.”

At this everybody felt uncomfortable, and Kay, instead of flying into his usual passion hung his head. He was not at all an unpleasant person really, but clever, quick, proud, passionate and ambitious. He was one of those people who would be neither a follower nor a leader, but only an aspiring heart, impatient in the failing body which imprisoned it. Merlyn repented of his rudeness at once.

I believe The Once and Future King is one of the great literary works of the last century. With The Sword in the Stone, it begins as the humorous story of a young boy’s education at the hands of a somewhat silly magician. Ladled over the book are great big dollops of detail about falconry, jousting and all sorts of medieval history as well as deep insights into the nature of the world. Through those insights, a story of greater scope and complexity is implied. In The Queen of Air and Darkness, the book takes on both a more hopeful and yet darker tone. Arthur conceives of a better England, but at the same time, the four Orkney brothers stand in direct contrast to him. They, as will be explored in the next two books, are unable to break free of the forces that warped and damaged them and will prove powerless to escape their upbringing and hunger for revenge.

Of all the books I’ve read for Black Gate, this is the best and my favorite. It speaks to the reader in several voices at once, all written beautifully and with great humanity. I cannot recommend The Once and Future King too highly. Neither can I say how much I look forward to finishing it and coming back here next month, despite the heartbreaking nature of The Ill-Made Knight and The Candle in the Wind.

Read Part 2 of the review here.

Note: There is a wonderful article by Karen Joy Fowler about how her activism was in part spurred by her encounter with The Once and Future King.

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column the first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

Thanks for this thoughtful review. This book has been turning up in conversation for me lately and i have just dug it out for a reread – i left it unfinished a couple of years ago.

I am wondering, though, do you think there is any nascent bigotry in white’s choice to make Morgaine’s family Scottish? I am always wary of the old habit of othering people north of london, a habit so old as to be virtually invisible to those not attuned to it. I’ll make my own judgement as I work my way through, but I was struck by this detail.

I’ll be curious as to your conclusion. I don’t think that would have been White’s approach. It would seem to fly too much in the face of his humanism. I think it’s simply that the Morgause and her sons are from the Orkneys (which White points out through Merlyn that Lot and his family aren’t even Celts but descended from Norse conquerors)

I first read The Once and Future King in college, in consequence of buying a library castoff. I read it again a few years later when I was running a campaign in the Chaosium game Pendragon. And once more, back in 2012, when my monthly sf/f reading group wanted to read The Sword in the Stone, but why stop there? The scenes that stick with me the longest are the animal sequences: the falcons in the mews, the geese flying high, the ridiculously regimented industrial society of the ants. And the sacrifice of the cat by Morgause. I could not do justice to its amazing mixture of solemn and silly, comic and tragic, in my King Arthur game (I was more under Ms. Bradley’s spell with her more seamless Mists of Avalon and its tragic heroine Morgan). But I did have a Questing Beast that was suspiciously amorous.

The animal sequences are brilliant, enough so I might actually read The Book of Merlyn. I was never able to get into Mists myself.

The Book of Merlyn reads like a draft of the similar animal sequences in Sword in the Stone, as they are the originals that were added to Sword when the first book was revised to be part of the tetralogy. Still worth reading.

Although I read all four books back in the day, the only two that really stick in my mind are the first (I have a soft spot for the Disney version) and the last. My memory is that the sequence was mostly written in Ireland and that White was recovering from a breakdown at the time. I really enjoyed them, albeit maybe not enough to re-read them.

They are the most memorable, but the other two are nearly as good.

For some reason, I’ve never quite gotten this one to the table. Probably time to do something about that.

absolutely

Is The Once and Future King in print?

Seeing this review reminded me of times 50 years or more ago, when there was a lot less fantasy in print — especially if you don’t count pulp fantasy (sword and sorcery). People would read Tolkien and wonder what else there was. And TOaFK might be mentioned, and The Last Unicorn, and the fantasies of Eddison and Peake… But there wasn’t a lot. Of what’s been published since, I don’t know if much is of comparable quality.

Well, a Tolkien reader can’t go wrong with Beagle, White and Peake. I’ve been daunted by Eddison too much to date

This has been on my shelf, unread, for decades (though I did hack my way through Mallory a few years ago). No time like the present, is there? I vow to read it before summer; thanks for the push, Fletcher!

I can’t wait to hear what you think.

I read The Once and Future King with two of my students, middle school brothers whose parents spoke only Mandarin. We met at their family’s restaurant after school. The boys were mad for Arthuriana, which they discovered by way of Garth Nix. We’d read all of the Old Kingdom books that had come out up to then, and worked our way through most of Nix’s short story collection. I told the boys the two Arthurian stories wouldn’t make sense if they didn’t know the tradition they were based on. Next thing I knew, we were sprinting through a modern-English rendering of Malory, and then slowing down to luxuriate in White. Took us a good six months. By the time I got to the end of Malory, Sir Gareth was the only character I would have wanted to meet socially. I ended up naming my first kid after him. People asked me at the time why I named my child after a character who died, but by the end of Le Morte D’Arthur, I think there are only two characters out of a cast of thousands who are still alive. At least Gareth lived and died honorably.

My favorite sentence in all of The Once and Future King, weirdly enough, is, “Here is the other one,” purely for reasons of craftsmanship. Two characters are stripping the armor off a fallen knight while discussing how they plan to get out of a trap. The narrator gives a meticulous description of a bit of armor from the shoulder or elbow, and has the characters struggle to remove it as they deliberate. They reach some tragic conclusion about their predicament, and, heartbroken, without any stage business from the narrator, one of the characters simply says, “Here is the other one.” We can picture them reassembling the armor, and all the body language that goes with that process, from the stark matter-of-factness and total lack of ornament of that sentence.

Great review of a great book (great books?); I look forward to Part 2. The Once and Future King is high on my always-reread list, especially because of the first two parts.

Merlyn and Arthur are so damn likable in their different ways. The magic is really magical (those wild geese! the hawks! the fish!), and even secondary and somewhat antagonistic characters like Kay are sketched in with sympathy.

I read it in an Arthurian Lit class in college. We started with Le Morte d’Arthur and then Idylls of the King. Most of the class found The Once and Future King to be wondrous palate cleanser.