A Jumble Sale of Fascinating Ideas: The Science Fiction of Arthur C. Clarke

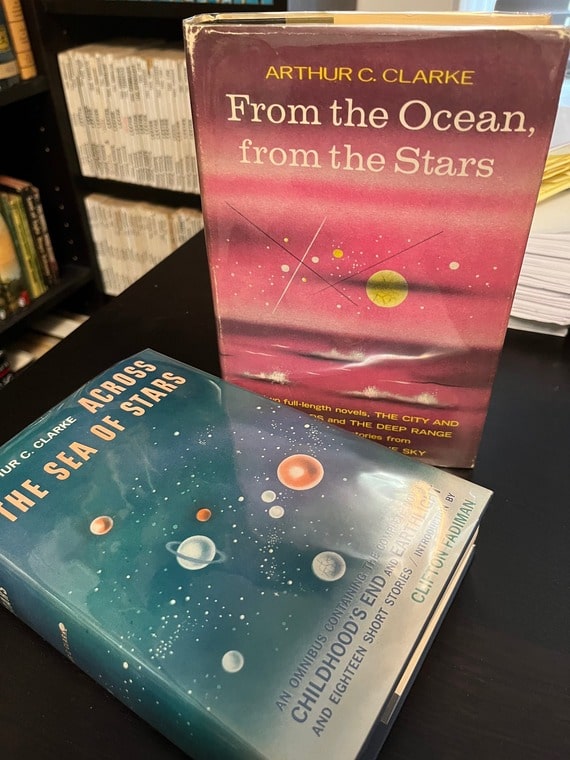

Across the Sea of Stars and From the Ocean, from the Stars,

two omnibus collections by Arthur C. Clarke (Harcourt, Brace & Co, 1959 and 1961)

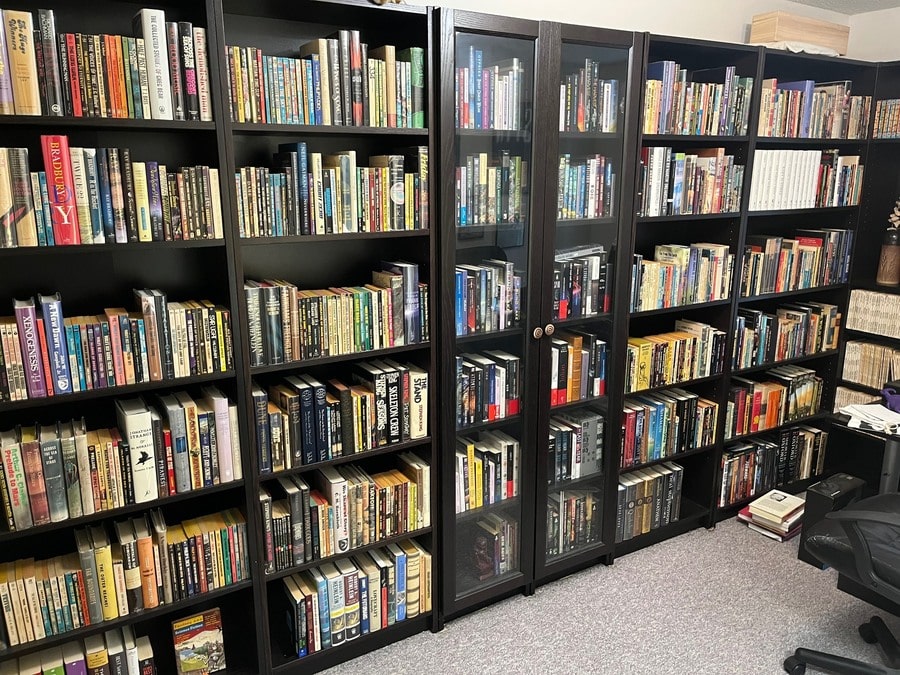

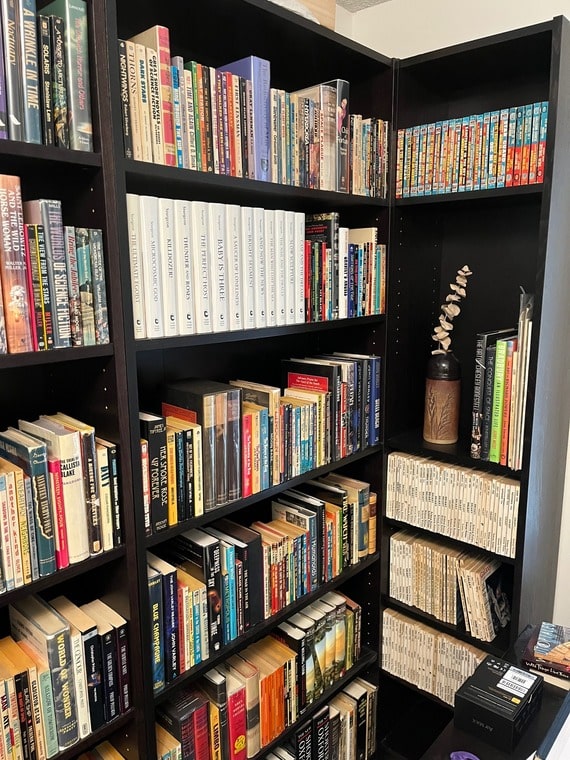

I’ve just about finished trimming and sorting my SF collection. It’s a pretty eclectic assortment: some of these books have personal meaning for me, some strike me as interesting for their cover art or their connection to the history of the genre, some are just old friends I’ve carried around for decades. Most fall into the category of post-war English-language SF up to about 1980, though there are more recent titles among them. I have other and more current titles elsewhere in the house, but this is where my heart is. (Maybe you can’t love a genre quite so wholeheartedly once you start publishing in it.)

All of which prompted me to re-read some classic SF, since I probably can’t trust the opinions I formed when I encountered these books at the age of 14 or 15. Case in point: Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End, as I originally discovered it: in the omnibus collection Across the Sea of Stars.

It’s still a deeply entertaining book, some 70 years since its first publication. Clarke’s writing, especially by comparison with his American contemporaries, seems reserved, precise, balanced, and strikingly lucid — perfect counterpoint to the subject matter, since what he’s giving you is a jumble sale of fascinating ideas: a first contact story, an alien occupation, a utopia-in-passing, an interstellar journey, the end of the world, human transcendence… The characters may not be particularly nuanced by modern standards, but neither are they superficial or implausible. And Clarke has a knack for describing things his characters don’t and can’t understand — a useful skill for an SF writer.

This week it was The City and the Stars, a novel I read as a teenager and about which I remembered essentially nothing. It’s a very old-fashioned tale-of-wonder — the kind of SF I once described as “miracle stories of the Enlightenment” — but I enjoyed it. The plot is one big, expanding arc of cosmological revelation, featuring robots and sentient cities and ancient spaceships and including a prescient description of what we now call virtual reality.

It also reminded me how seriously SF writers of that generation took the idea of telepathy and other “hidden powers of the mind.” I guess they had J.B. Rhine’s now-debunked research to justify them, but it feels more like something borrowed from theosophy or 19th-century spiritualism — and it sits a little uncomfortably next to Clarke’s otherwise impeccable rationalism. But science fiction has always been a philosophical jumble sale, so that’s fine.

It was especially enjoyable to read these stories in the same gorgeous omnibus editions I used to borrow from the local library. Armchair time travel! But I have a stack of more recent books calling my name.

Robert Charles Wilson is the author of the Hugo Award-winning Spin and many other books. His last piece for Black Gate was Robert Bloch’s Pocket History of Science Fiction Fandom. This article originally appeared in a pair of posts on Facebook. Reproduced with permission.

When first I read sf, the Big Three (Asimov, Clarke, Heinlein) were just starting to lose their grip on the field. I was an Asimov fan, because his humor and his ‘jumpy’ prose that liked to spring surprises on the reader appealed to me. But even then, I thought Clarke was the smoothest, most polished writer of the 3, and I enjoyed his exposition and the even flow of his writing. I might almost call him “textbook” in his gradual build, but according to the terms of the Asimov-Clarke Treaty, he was the second-best science writer of the pair.