Ellsworth’s Cinema of Swords: Mondo Mifune

Vendetta of a Samurai (Japan, 1952)

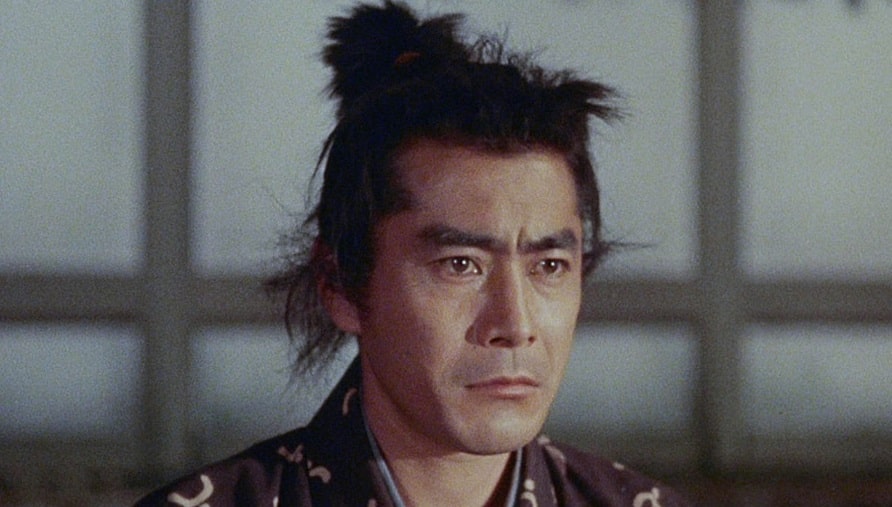

If American and European film fans recognize only one Japanese actor, it’s the great Toshiro Mifune (1920-1997), who came to prominence in the west for his collaborations with director Akira Kurosawa — not just the historical films such as Rashomon (1950), Seven Samurai (1954), and Yojimbo (1961), but also Kurosawa’s acclaimed crime movies such as The Bad Sleep Well (1960) and High and Low (1963).

Mifune had a broad range, with the ability to inhabit a wide variety of characters of all sorts, though he had the kind of classically handsome face with regular features that often limit actors to matinee idol roles. A broadly physical actor when the role required, at need he could convey deep emotion by subtle changes of facial expression. Mifune was an ambitious actor who acknowledged few limitations, and he worked with many other leading directors other than Kurosawa, often co-producing on projects he felt strongly about. This week we’re taking a look at three of his lesser known features, movies that exhibit considerable diversity just in the genre of chambara swordplay films.

Vendetta of a Samurai

Rating: ****

Origin: Japan, 1952

Director: Kazuo Mori

Source: Toho DVD

With a screenplay by Akira Kurosawa, Toshiro Mifune in the lead, and about half the cast of Seven Samurai in support roles, this very nearly qualifies as a Kurosawa samurai film, but there’s more High Noon in this than Seven Samurai. Ably directed by Kazuo Mori, who oversaw a number of Zatoichi movies and TV episodes, as well as the similarly titled Samurai Vendetta (1959), this is a remarkable film, a revisionist chambara made while the genre was still establishing its tropes.

Kurosawa sets out to tell the story of the celebrated samurai showdown at Kagiya Corner in 1634, when the sword trainer Mataemon Araki helped his brother-in-law Kazuma achieve his revenge on the murderer Matagoro despite the protection of a rival clan. At the start, we see the combat as it’s been depicted in popular fiction, an exaggerated kabuki-dance of orchestrated swordplay as Mataemon bloodlessly defeats a platoon of bodyguards. But before the fight is over, a narrator interrupts to tell us that what we’ve been seeing is just a figment, while the real story, and the real people behind it, are far more interesting.

The rest of the film is the historic backstory of the real participants in the showdown, leading to a shattering climax in a horrific street brawl (with katanas). After killing young Kazuma’s brother, Matagoro (Minoru Chiaki) takes refuge with a clan in Edo into which he’s married. The honor code demands vengeance, and because Mataemon (Mifune) is Kazuma’s brother-in-law, he must help him, even though this pits him against his best friend Jinza (Takashi Shimura), who is related by marriage to Matagoro.

The bulk of the movie takes place in the hour before the duel, as Mataemon and his three allies wait for Matagoro, Jinza, and company to arrive at Kagiya Corner and get ambushed. Facing possible death, the waiting samurai, none of whom have ever drawn a sword in real combat, contemplate their past lives in flashbacks that are elegiac and moving, between which Mataemon utters gnomic remarks like, “Waiting is hard,” and, “Don’t think about surviving.” Gosh, thanks!

When the opponents do arrive and begin their final approach to the pair of teahouses where Mataemon and his comrades await them, the suspense is so thick you could cut it with a wakizashi. Fear is present like a fifth member of the attack team. The fight itself, when it breaks out, is utterly awful and utterly convincing. And all those personal flashbacks, with their songs and stories and hopes and dreams, seem suddenly significant.

Life of a Swordsman (or Life of an Expert Swordsman or Samurai Saga)

Rating: ***

Origin: Japan, 1959

Director: Hiroshi Inagaki

Source: Samurai DVD

On a stage before an audience of commoners and nobles, a celebrated singer begins a performance. A voice rings out from the crowd, commanding the singer to leave the stage. Hasn’t she been forbidden to perform? The singer, shaken, looks to the nobles for support, and upon receiving their nods, continues her performance. The owner of the voice strides onto the stage, a swordsman whose face is distorted by a grotesque nose. He chases the singer away, and when the nobles draw their weapons to chastise him, the swordsman defeats them handily while simultaneously composing a poem about it.

Sound familiar? It’s the opening of Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac, rendered here as a samurai melodrama by top director Hiroshi Inagaki, with Toshiro Mifune in the Cyrano role! The play fits the Edo period like a gauntlet, scarcely anything needing to be changed other than proper names and background politics. It’s 1599 in Edo (i.e., Tokyo), and the samurai Komaki (Mifune), swordsman and poet, belongs to the faction supporting Lord Hideyoshi, but the Tokugawa samurai are increasingly aggressive, targeting Komaki and his friends for death in street skirmishes.

The young and handsome Jurota (Akira Takarada), another Hideyoshi supporter newly arrived from the provinces, catches the eye of Lady Ochii (Yoko Tsukasa). Beautiful, sensitive, and poetic, Lady Ochii’s sure Jurota must be the same, and asks Komaki, who’s known her since they were young, to introduce her to the newcomer. Komaki, though secretly in love with Ochii himself, does so, but Jurota is so inarticulate that Ochii dismisses him. Jurota is smitten, however, and begs the famously eloquent Komaki to write his love letters and speeches for him.

You probably know where it goes from there, as this is a closer adaptation of Cyrano than most. Mifune’s prosthetic nose, while broad and ugly, wouldn’t warrant a second look on a European street, but in Edo it’s a deformity, and Komaki is extremely sensitive about it. Mifune delivers a theatrical but nuanced performance that’s appropriate for a samurai Cyrano, but sadly no one else in the cast is in his league. This is a lesser Inagaki film, but that still puts it head and shoulders above most of its competition of the time. The soundtrack by the always excellent Akira Ifukube is particularly good.

This adaptation has considerably more action in it than Rostand’s play — the katanas come out early and often, and the swordplay is quite good. Instead of a siege between French and Spanish cavaliers, here the conflict between factions ends in the decisive Battle of Sekigahara (1600) — with Komaki and his friends on the losing side. The finale takes place twelve years later, in the same month in which Sasaki Kojiro was defeated in a famous duel by Musashi Miyamoto… as portrayed in Samurai III (1956) by Inagaki and Mifune!

Samurai Assassin

Rating: ****

Origin: Japan, 1965

Director: Kihachi Okamoto

Source: Warrior DVD

This is a film that aims high but doesn’t quite hit all its targets. Set in 1860, during the unrest of the Bakumatsu period, its subject is the Sakurodamon Incident in which an elder lord of the Shogunate is ambushed by dissidents — or so it seems at first. For there’s a lot more involved here, maybe too much for one movie.

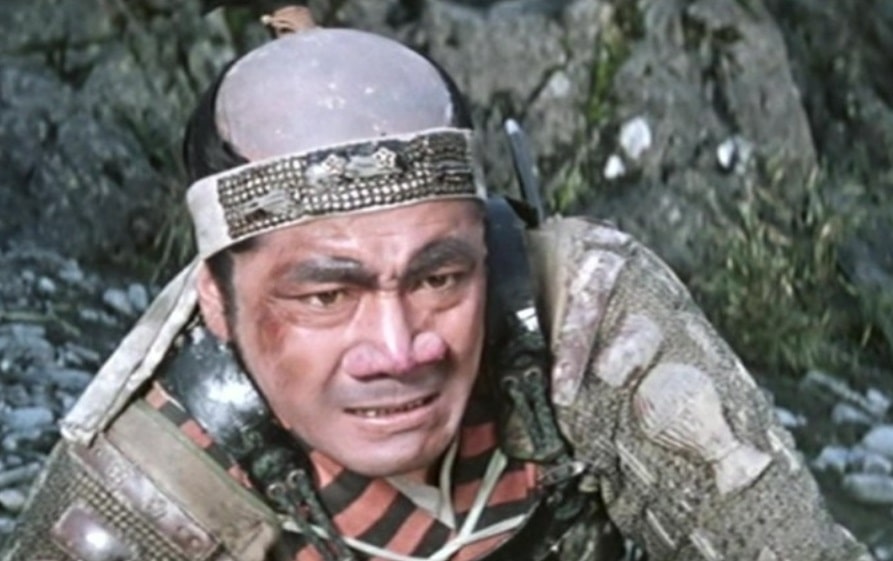

The film starts with the events of February 17, 1860, presented in documentary style, complete with narrator, in high-contrast black-and-white. Samurai of the Mito clan, who’ve decided that Lord Naosuke must be assassinated for making a humiliating treaty with the Western powers, are gathering in the snow outside Edo Castle’s Sakurodamon gate. As they wait, tense, blood pounding, other lords’ processions one by one enter the castle, but not Naosuke’s. As the time for the castle ceremony passes, the Mito must face the fact that Naosuke isn’t coming; furtively, they withdraw, regathering at a nearby tavern to discuss what went wrong.

The Mito leaders, who’ve been betrayed before, conclude that Naosuke didn’t show because he’d been tipped off about the ambush. One of their number must be a traitor! Their suspicions quickly settle on two outsiders among them: Kurihara (Keiju Kobayashi), a scholar from another clan who joined their cause for ideological reasons, and Niiro (Toshiro Mifune), an angry and drunken ronin who joined because he is desperate for action, and for the rewards of its success. More suspicious yet, these two polar opposites are good friends.

As the Mito investigate the background of the suspected traitors, the nature of the story changes into discovery of Niiro’s secret history and how he descended from promising young fencing expert to bitter loner. Piece by piece, we learn of his background as the unrecognized son of a high lord secretly born to a samurai concubine, of his frustrated romance foiled because he doesn’t know his father’s name, and his violent reactions to a succession of disappointments, until finally he joins the Mito dissidents and finds a friend in the scholarly swordsman Kurihara.

And it is that friend, Kurihara, whom the Mito leaders conclude must be the traitor who’d warned Naosuke: Kurihara, whose sword skills are so great that among the Mito, only Niiro is his match. Niiro is ordered to either execute Kurihara or be expelled from the patriotic cause. Meanwhile, the secret of Niiro’s parentage, long suppressed, is finally on the verge of being revealed. And then another great procession to the castle is announced, to include Lord Naosuke and his retainers, and the assassination is on again!

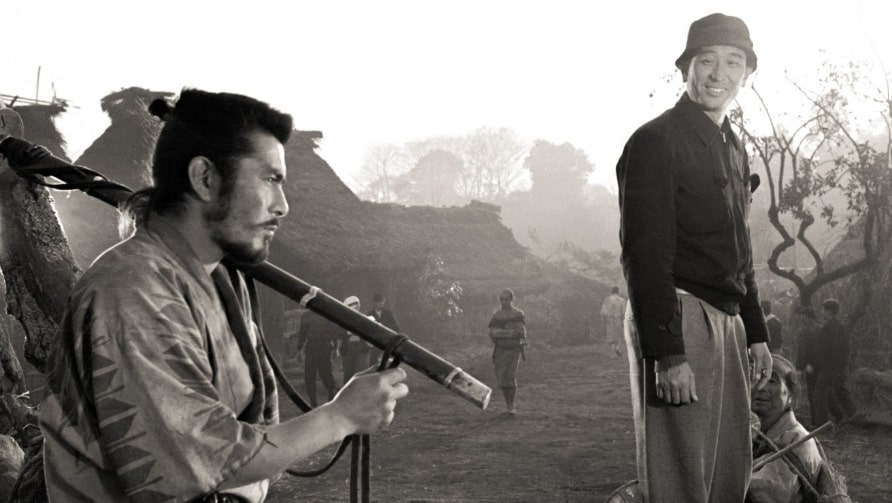

Co-produced by and starring Mifune, Samurai Assassin is directed by Kihachi Okamoto, who had made such an impression with Warring Clans, his debut, two years earlier. Okamoto’s mastery of black-and-white filmmaking is on full display here, and the resulting look is beautiful one moment and utterly grim and stark the next. For the final assassination attempt, the movie reverts to its documentary approach, and it’s a rather jarring transition, frankly. However, the climactic mass mêlée in a driving snowstorm outside the gates of Edo Castle is brilliant, one of the most harrowing samurai sword battles ever filmed. It’s too bad that it’s followed by an ending of unbelievably heavy-handed, in-your-face irony. Otherwise, Samurai Assassin would be a must-see.

Where can I watch these movies? I’m glad you asked! Many movies and TV shows are available on disk in DVD or Blu-ray formats, but nowadays we live in a new world of streaming services, more every month it seems. However, it can be hard to find what content will stream in your location, since the market is evolving and global services are a patchwork quilt of rights and availability. I recommend JustWatch.com, a search engine that scans streaming services to find the title of your choice. Give it a try. And if you have a better alternative, let us know.

Previous installments in the Cinema of Swords include:

The Barbarian Boom, Part 4

Blood-Red and Blind: The Crimson Bat

Updating the Classics

Sink Me! Scarlet Pimpernels!

The Barbarian Boom, Part 5

Alexandre/Alexander

Musashi and Kojiro

Forgotten Fantasies

More o’ Zorro

Laugh, Samurai, Laugh

Boarding Party Bingo

They Might Be Giants

LAWRENCE ELLSWORTH is deep in his current mega-project, editing and translating new, contemporary English editions of all the works in Alexandre Dumas’s Musketeers Cycle; the fifth volume, Between Two Kings, is available now from Pegasus Books in the US and UK, while the sixth, Court of Daggers, is being published in weekly instalments at musketeerscycle.substack.com. His website is Swashbucklingadventure.net. Check them out!

Ellsworth’s secret identity is game designer LAWRENCE SCHICK, who’s been designing role-playing games since the 1970s. He now lives in Dublin, Ireland, where he’s a Narrative Design Expert for Larian Studios, writing Dungeons & Dragons scenarios for Baldur’s Gate 3.

I haven’t seen any of these films, but now I want to. Mifune was a very talented actor.

Another Ellsworth’s Cinema of Swords? And with More Mifune? Zowie!

I’ve never even heard of any of these films and now I’d like to see all of them! Thank you again, Mr. Ellsworth, for pointing us towards fascinating films we might never have heard of otherwise.