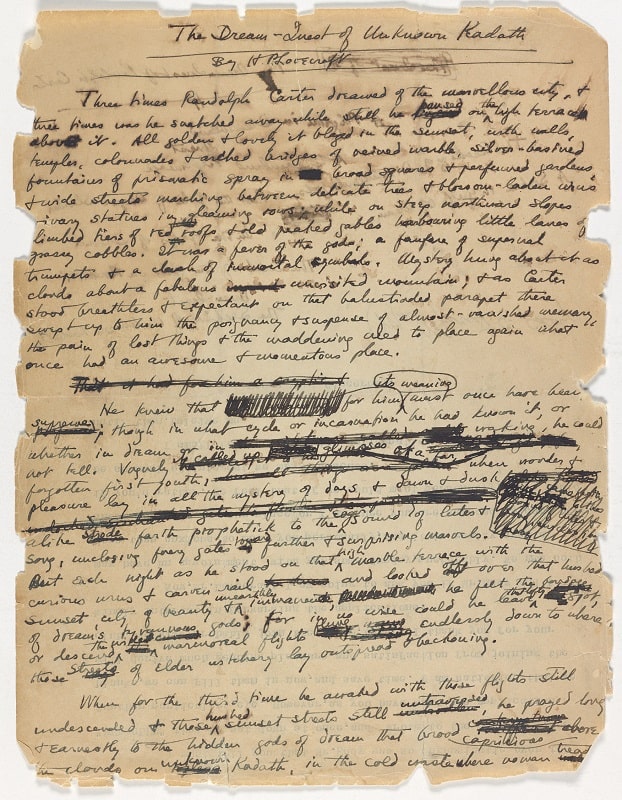

A Strange Song of Unknown Places: The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath by H.P. Lovecraft

HPL’s original manuscript

Three times Randolph Carter dreamed of the marvelous city, and three times was he snatched away while still he paused on the high terrace above it. All golden and lovely it blazed in the sunset, with walls, temples, colonnades and arched bridges of veined marble, silver-basined fountains of prismatic spray in broad squares and perfumed gardens, and wide streets marching between delicate trees and blossom-laden urns and ivory statues in gleaming rows; while on steep northward slopes climbed tiers of red roofs and old peaked gables harbouring little lanes of grassy cobbles. It was a fever of the gods, a fanfare of supernal trumpets and a clash of immortal cymbals. Mystery hung about it as clouds about a fabulous unvisited mountain; and as Carter stood breathless and expectant on that balustraded parapet there swept up to him the poignancy and suspense of almost-vanished memory, the pain of lost things and the maddening need to place again what once had been an awesome and momentous place.

HP Lovecraft (1890-1937) was a man who seems to have never been fully comfortable in the world. His racism, most unpleasantly, but also, his old-fashioned affectations and his adamant refusal to bend his artistic desires to the least sort of commercial demands, all these, I believe, indicate a severe unease with the way the world was (he even turned down the editorship of Weird Tales because he refused to move to Chicago “on aesthetic grounds.”) The old America, peopled by the heirs of the original colonial families, had been washed away on a tide of industrialization and immigration. It was decadent and in decline and he would not be a part of it.

From his earliest days, Lovecraft was plagued by strange dreams and nightmares. Many of these would serve as the basis of stories later in life. A tragic family life — his father died in an asylum of late-stage syphilis and his family slowly slipped into poverty — and an innate nervous disposition probably had much to do with his attitudes. At the heart of the horror stories for which he’s most famous is the belief that mankind is insignificant and powerless in the face of a vast and uncaring Universe. While I don’t think he was mentally ill or anything, I do believe he longed for some intangible, more fantastic and better world.

Not finding one at hand, he created one in a series of related tales that culminated with The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath in 1927 (though it wouldn’t be published until 1943). Typically referred to as his Dream Cycle, Lovecraft was greatly influenced in writing these tales by Lord Dunsany‘s lush stories. The stories are filled with dense descriptive passages, surreal imagery, and the illogical logic of dreams.

Randolph Carter, a stand-in for HPL himself, and the protagonist of several other stories, has dreamed of a fantastical city three times and each time been pulled away from it and back to the waking world. An experienced dreamer, he sets off to discover its location by petitioning the gods of the dreamworld, beings who seem intent on preventing him from reaching the city. They live on top of a mountain called Kadath, a place that’s location is unknown. With information extracted from a priest he gets drunk, Carter formulates a plan to locate Kadath. It involves climbing a mountain topped by a giant bust of one of the gods, then, based on its features, find the region of men who are the children of the gods by comparing facial features. That’s where the gods, regularly getting their children on mortals, will be. It’s, amazingly, a plan that succeeds. I was actually surprised at all this, finding there’s an actual mystery in Dream-Quest and Carter has to set out with detective-like diligence to solve it.

Following a long series of increasingly dangerous and elaborate adventures, Carter enters the palace of the gods only to find they’ve abandoned their old home for the city of his dreams. In the end, he discovers that that dream-city he desires so much is no more than a construction composed of his memories of the real world of Boston and New England that he loves deeply.

Rereading this short novel for the first time in several decades and right after reading Dunsany’s At the Edge of the World collection, I was very happy how much I enjoyed it. Lovecraft himself was not altogether happy with the finished story, writing “Randolph Carter’s adventures may have reached the point of palling on the reader; or that the very plethora of weird imagery may have destroyed the power of any one image to produce the desired impression of strangeness.” While the story’s prose wanders towards the overly-luxuriant, the effect of the story is never not one of wonderful and exuberant strangeness. From his initial travels through the enchanted woods of the Zoogs to being carried across the void towards the Azathoth, the blind, idiot god at the center of the universe, Lovecraft pulled out all the stops and let his imagination run riot.

Strange and discomfiting sights above and below are common occurrences in the Dreamlands. While making his first ocean voyage from the great trading city Dylath-Leen, Carter catches sight of a great ruined city under the ocean.

That night the moon was very bright, and one could see a great way down in the water. There was so little wind that the ship could not move much, and the ocean was very calm. Looking over the rail Carter saw many fathoms deep the dome of the great temple, and in front of it an avenue of unnatural sphinxes leading to what was once a public square. Dolphins sported merrily in and out of the ruins, and porpoises revelled clumsily here and there, sometimes coming to the surface and leaping clear out of the sea. As the ship drifted on a little the floor of the ocean rose in hills, and one could clearly mark the lines of ancient climbing streets and the washed-down walls of myriad little houses.

Then the suburbs appeared, and finally a great lone building on a hill, of simpler architecture than the other structures, and in much better repair. It was dark and low and covered four sides of a square, with a tower at each corner, a paved court in the centre, and small curious round windows all over it. Probably it was of basalt, though weeds draped the greater part; and such was its lonely and impressive place on that far hill that it may have been a temple or a monastery. Some phosphorescent fish inside it gave the small round windows an aspect of shining, and Carter did not blame the sailors much for their fears. Then by the watery moonlight he noticed an odd high monolith in the middle of that central court, and saw that something was tied to it. And when after getting a telescope from the captain’s cabin he saw that that bound thing was a sailor in the silk robes of Oriab, head downward and without any eyes, he was glad that a rising breeze soon took the ship ahead to more healthy parts of the sea.

Lovecraft was a cat person and as such, so is Randolph Carter. Despite being on friendly terms with the Zoogs, a tentacled race of possibly little, man-eating creatures, Carter has not a moment of hesitancy when he discovers they plan to go to war with the Dreamlands’ cats about who he’ll side with.

Carter now outlined the peril of the cat tribe, and was rewarded by deep-throated purrs of gratitude from all sides. Consulting with the generals, he prepared a plan of instant action which involved marching at once upon the Zoog council and other known strongholds of Zoogs; forestalling their surprise attacks and forcing them to terms before the mobilization of their army of invasion. Thereupon without a moment’s loss that great ocean of cats flooded the enchanted wood and surged around the council tree and the great stone circle. Flutterings rose to panic pitch as the enemy saw the newcomers and there was very little resistance among the furtive and curious brown Zoogs. They saw that they were beaten in advance, and turned from thoughts of vengeance to thoughts of present self-preservation.

At one point, facing a severe reversal in his fortunes, Carter determines to undertake a dangerous subterranean journey with the help of a group of ghouls. Despite their charnel nature, he has found in those creatures close and reliable allies.

Suddenly their desperation was magnified a thousand fold by a sound on the steps below them. It was only the thumping and rattling of the slain ghast’s hooved body as it rolled down to lower levels; but of all the possible causes of that body’s dislodgement and rolling, none was in the least reassuring. Therefore, knowing the ways of Gugs, the ghouls set to with something of a frenzy; and in a surprisingly short time had the door so high that they were able to hold it still whilst Carter turned the slab and left a generous opening. They now helped Carter through, letting him climb up to their rubbery shoulders and later guiding his feet as he clutched at the blessed soil of the upper dreamland outside. Another second and they were through themselves, knocking away the gravestone and closing the great trap door while a panting became audible beneath. Because of the Great One’s curse no Gug might ever emerge from that portal, so with a deep relief and sense of repose Carter lay quietly on the thick grotesque fungi of the enchanted wood while his guides squatted near in the manner that ghouls rest.

I was surprised that most of my memories of the Dream-Quest were limited to the first half of the novel. Admittedly, it is composed of a series of discrete and very visual sequences, including a full-fledged battle on the Moon’s dark side. The back half, it turns out, though, is just as wild. As Carter nears his Kadath, reaches it, and finally heads toward his ultimate goal, great forces are arrayed against him, ranging from the gelatinous moon-beasts and great elephantine horse-headed birds all the way to Nyarlathotep, Azatoth’s emissary. Never once does Lovecraft’s story fail to feel strange and unsettling and it never stops moving. As he nears Kadath, Carter seems no longer in charge of his own actions but is drawn relentlessly toward it and, maybe, his doom.

Then suddenly the clouds thinned and the stars shone spectrally above. All below was still black, but those pallid beacons in the sky seemed alive with a meaning and directiveness they had never possessed elsewhere. It was not that the figures of the constellations were different, but that the same familiar shapes now revealed a significance they had formerly failed to make plain. Everything focussed toward the north; every curve and asterism of the glittering sky became part of a vast design whose function was to hurry first the eye and then the whole observer onward to some secret and terrible goal of convergence beyond the frozen waste that stretched endlessly ahead. Carter looked toward the east where the great ridge of barrier peaks had towered along all the length of Inquanok and saw against the stars a jagged silhouette which told of its continued presence. It was more broken now, with yawning clefts and fantastically erratic pinnacles; and Carter studied closely the suggestive turnings and inclinations of that grotesque outline, which seemed to share with the stars some subtle northward urge.

I was sorely disappointed with Dream-Quest‘s conclusion when I first read it in my younger days. When Carter realizes his dream city is no more than a reflection of the city and land “the fair New England world that had wrought him,” I felt a little betrayed. Now, a much older man whose home no longer resembles or feels like that of that long ago time when I first traveled alongside Randolph Carter I found it a poignant and resonant conclusion to his odyssey.

This is the last real story Lovecraft’s Dream Cycle. He wrote a few more stories obliquely connected to it, but they are far more aligned with his horror tales. “Through the Gates of the Silver Key” (1934), co-written with E. Hoffman Price, is the final tale of Randolph Carter, but it’s more of a theosophical adventure than a tale of the Dreamlands. There’s a real sense of finality to Dream-Quest, both artistically and philosophically. It’s almost as if he had the same realization and made the same decision Carter did; accept the beauty of the real world and remain part of it.

The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath is a fantastic read. It never falters in creating an outlandish and striking atmosphere or propelling the reader and Carter forward toward distant Kadath. Sometimes the prose is too, too much, but I never found it detrimental to Lovecraft’s storytelling or scene-setting. Some of his shorter Dream stories are slight; Dream-Quest is not. It serves as a real culmination to his Dunsananian stories, expanding the scale and scope of his Dream Cycle to epic proportions. It feels as if there’s nowhere else to go after the final paragraph. I believe it compares favorably to his other long works, The Case of Charles Dexter Ward (1927) and At the Mountains of Madness (1931) as well as the greater body of his work. If you haven’t encountered this part of Lovecraft’s writing, I recommend it.

NOTE: This novel has served as inspiration for several other writers. Brian Lumley, foremost, has written a quartet of sword & sorcery novels set in the Dreamlands. Jason Bradley Thompson created a comic from the tale. I haven’t read it, but the panels I’ve seen from it are quite good. Finally, most recently, Kij Johnson wrote The Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe, the story of a woman from the Dreamlands journeying into the waking world. Also, Chaosium produced an incredibly designed Dreamland supplement for the Call of Cthulhu RPG.

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

This has always been somewhere in my top three or five favorite Lovecraft stories.

I like Dream Quest, but I definitely think it’s more of an acquired taste. As if any Lovecraft wasn’t nowadays, but DQ takes even more effort at acquiring than many of his other tales.

Unless you’re a Dunsany fan already, or have a propensity for Dunsanian-style myth and lyricism. If you’re into that classic mode, HPL’s Dreamlands stories grab you instantly. They grabbed me that way, and are still my favorite of all his work.

I was startled by how readable it is. It flowed more naturally than does some of his dialect-heavy horror writing

It has been a long time since I read Dream-Quest, I should probably delve into it again. I remember that the story seemed to bound from one situation to another–not always in a good way, but it did have its charm.

Loved this article. I’ve tried reading this twice and did not finish….even though this should be right up my alley. Perhaps a third visit will work.

One of the interesting thing about KADATH (and the rest of the DL tales) is that the protagonist is NOT a “warrior” or some kind of hero. He’s just a pretty “normal” guy in this fantastica dreamworld–and apparently a reclusive “loser” in the real world (an analog of HPL’s melancholy, loneliness, and disillusion with the modern world). If the protag had been a soldier or a swashbuckler, DREAM-QUEST could have easily been Sword-and-Sorcery (or what would have been come to be known as S&S–i.e. Howardian adventure). It would have been more like Robert E. Howard, and HPL had no interest in being REH–he was trying to be Dunsany (to a large degree) with these tales. But even Dunsany had his sword-swinging heroes. I think what makes DREAM-QUEST OF UNKNOWN KADATH more of a horror story than an adventure story is that the protagonist is so minute and ineffective, swept along by the strange currents of the Dreamlands. Ultimately, he passes through terror in search of meaning, but finds no meaning at all. After all, it’s only a dream. He wakes back in the boring ol’ waking world. Overall, it’s an extended nightmare–an adventure into weirdness and unreality that never falls back on the tropes of fantasy that might serve to reassure a reader. Tolkien wanted you to feel great and inspired; HPL wanted you to cower in the face of overwhelming nothingness. The best word to describe DREAM-QUEST is probably “phantasmagorical.” It’s an epic nightmare full of dark beauty and creeping strangeness.

Definitely give it another try. As I wrote above, I found the writing much better than I remembered and it feels more natural than some of his horror does