Thomas M. Disch: Love and Nonexistence

|

|

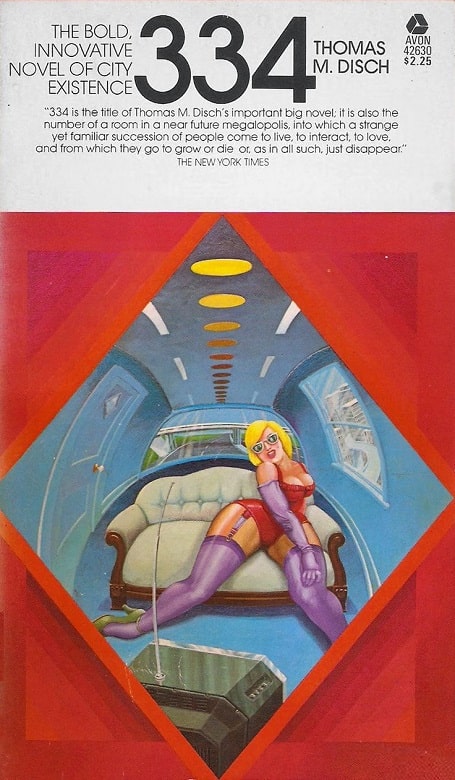

334 by Thomas M. Disch (Avon, October 1974). Cover artist unknown

In the last page of Thomas M. Disch’s novel 334, the family matriarch, Mrs. Hansen, has finished explaining why she should have the right to die. “I’ve made sense, haven’t I? I’ve been rational?” she asks her unseen auditor, a civil servant taking an application. “They’re all good reasons, every one of them. I checked them in your little book.” She has indeed given reasons why her life is no longer worth living, with disconcerting thoroughness, and makes clear that if her application is turned down, she will appeal. “I dream about it. And I think about it. And it’s what I want.”

What is remarkable about this scene is not the defense of suicide (which does not take place in the text — the book ends with Mrs. Hansen’s summation), but an articulated yearning for nonexistence. The three elements of this nexus — the voiced eloquence, the fiercely focused desire, and the prospect of nothingness — constitute three compass points of Disch’s art. There is a fourth, always present but harder to see, which we will come to in a moment. For now, let us consider these elements, vividly present throughout Disch’s fiction and widely remarked upon, but also widely misunderstood, especially in the SF genre, where he began his career and which he never fully left.

[Click on the images for larger versions.]

|

|

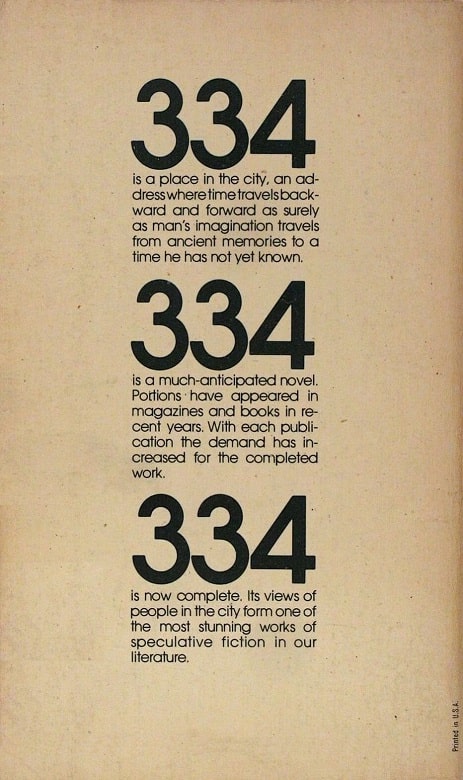

Camp Concentration by Thomas M. Disch (Avon, June 1971). Cover artist unknown

Disch’s immediately preceding novel, Camp Concentration, also dealt with the prospect of looming death, although this time his protagonist not only resists it but prevails. Its closing lines — “Much that is terrible we do not know. Much that is beautiful we shall still discover. Let’s sail till we come to the edge” — sound like a heroic antithesis to those of 334, but the contrast is only apparent. Mrs. Hansen has come to the edge, and since there is no longer anything terrible she does not know, nor much that is beautiful still open to her, she declares that the sail is over.

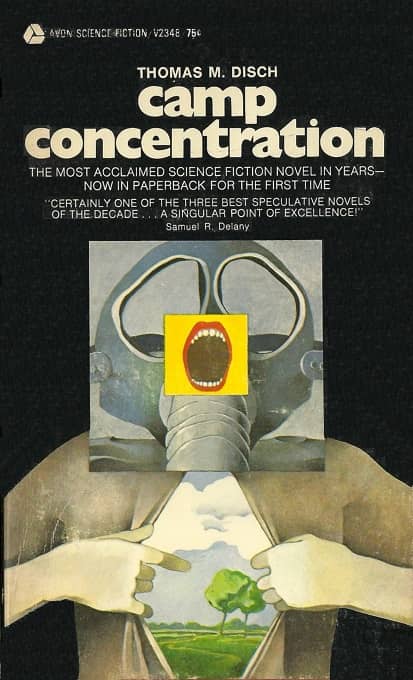

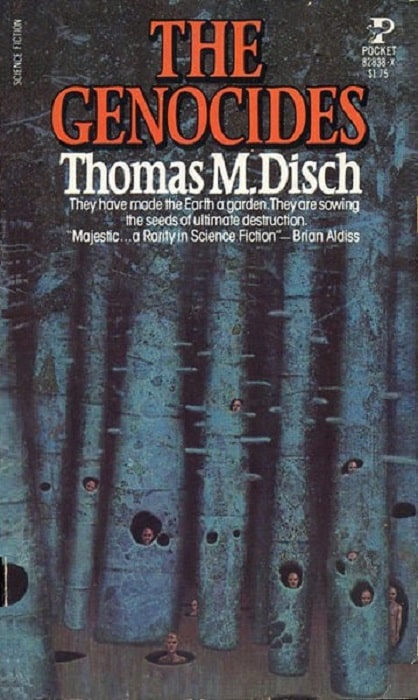

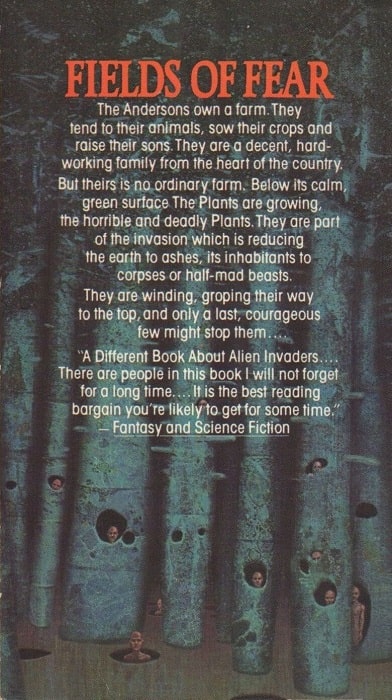

That Thomas M. Disch — who published a major collection under the title Getting into Death (which contained, in addition to the title story, a piece called “Death and the Single Girl”) was much preoccupied by death seemed obvious even to his most obtuse critics. His first novel, The Genocides, deals with that (surprisingly) rarest of themes, an alien invasion which actually succeeds. Given the overwhelming technical superiority, not to mention the element of surprise, which an invasion from the stars can be assumed to have, it is telling that no writer of U.S. genre science fiction — which prided itself on its unflinching acknowledgement of truths — had dramatized a successful one. Disch’s aliens convert the earth’s surface into a vast agribusiness, and when the last remnant of humanity rebels, they exterminate it like a pest. This coolly impersonal operation is dramatically posed against the passion of Disch’s doomed protagonists, and when Algis Budrys, in a prominent Galaxy review, declared Disch a “nihilist” and the book derivative of J.G. Ballard, Disch was deeply annoyed.

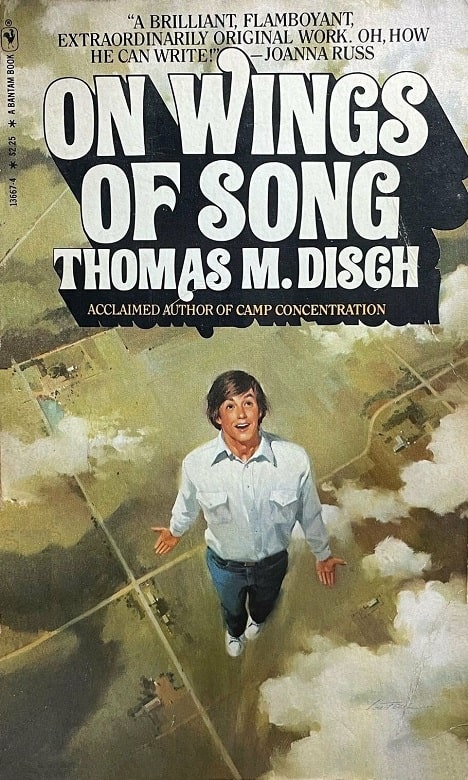

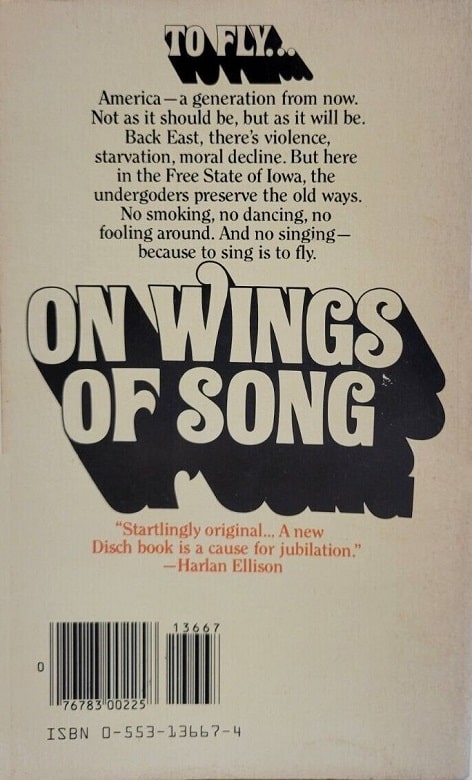

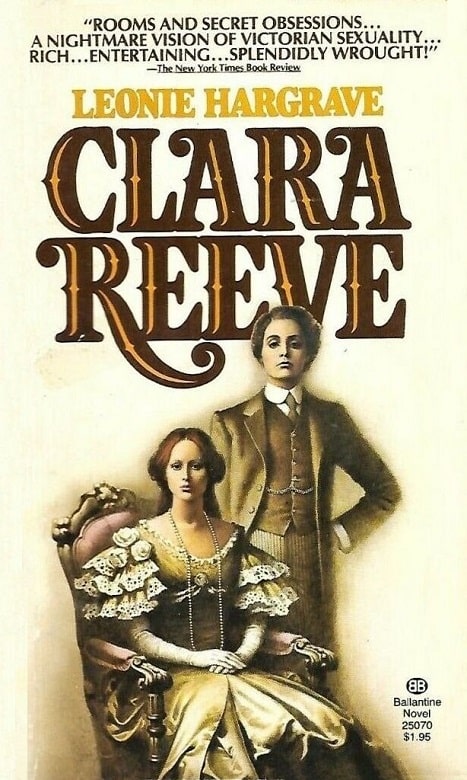

If The Genocides and 334 both struck the genre’s conventional critics as “pessimistic” — a term often hurled at writers identified with SF’s New Wave — they also shared a more interesting feature (one rarely seen in the fiction of Michael Moorcock, M. John Harrison, James Sallis, Joanna Russ or any of the other writers of the time with which Disch was variously associated): a deep and abiding concern with domesticity. Disch’s next novels — Clara Reeve, On Wings of Song, The Businessman: A Tale of Terror — all dealt with families, and if the families seemed at times fairly dysfunctional, they nevertheless did function, whether his astringently unsentimental portrayal of how families actually behave pleased genre sensibilities or not. On Wings of Song mediates between the family-oriented world of Amesville, Iowa and the adults-only milieu of a decaying Manhattan, but young Daniel Weinreb does his best to sustain a family in both phases of his life.

|

|

The Genocides by Thomas M. Disch (Pocket Books, September 1979). Cover artist unknown

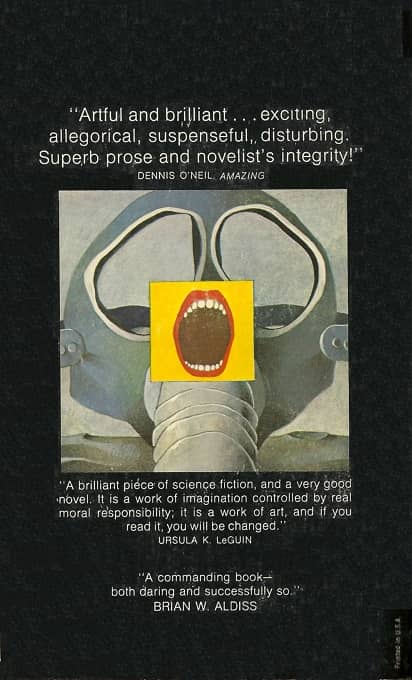

Like many Disch protagonists, he is also an aspiring artist, whose ferocious ambition (not all yearning is for death) goes some distance toward overcoming a lack of significant talent. Singing with genuine artistry allows one, in this world, to achieve a (tech-assisted) out-of-body experience, a rapture that partakes both of immortality and of physical demise. On the novel’s last page, the protagonist has once more sailed to “the edge,” although this time the text is ambiguous as to whether he crossed it or not.

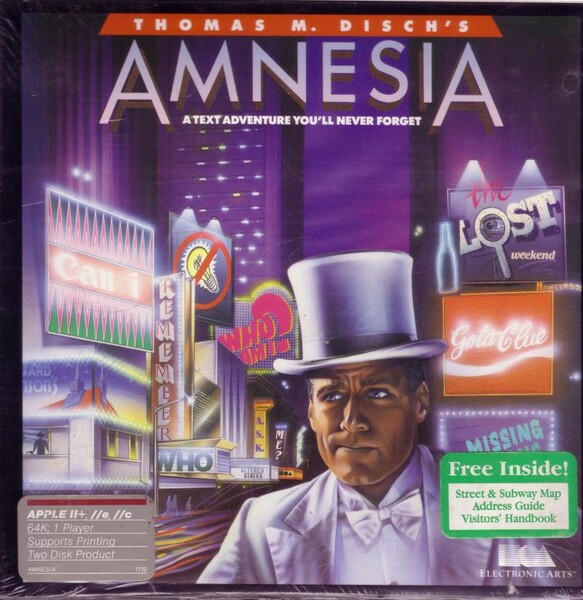

In a moving tribute, John Clute speaks of Disch’s “death-haunted” fiction and of his conviction that the only way to make sense of the human condition “was to treat death as a game, deadly of course, but beauteous.” The playfulness and formal deliberation that this implies was evident in Disch’s verse and in his dramatic writings (which included plays, opera libretti, and the interactive computer game Amnesia), but his fiction tended to dramatize a fascination with the prospect of nonexistence, a state of being (or nonbeing) that could be approached and contemplated, its borders negotiated, like an edge. It was a point of pride for Disch that his sequence of fantasy novels set in contemporary Minnesota were each based on a formal premise unique in literature to that work — the demonic child conceived by a murderer upon his victim in The Businessman; the magical caduceus that cured and blighted in equal measure in The M.D.: A Horror Story — but looking at the quartet today, I am most struck by the books’ recurrent evocations of a realm beyond ours, which grew more metaphysically extravagant with each volume.

Heaven in The Businessman can be accessed by the newly deceased through the escalator in the Sears Building in Minneapolis; while a genuine theophany puts the young protagonist of The M.D. in contact with a god, and the essence of evil in The Sub: A Study in Witchcraft “resembled layer upon layer of delicate dark lace billowing about the smoke house, swelling and shrinking like the translucent membranes of a sea anemone, rising sometimes above the small building like a plume of smoke from the chimney, and other times spreading through the underbrush like cilia . . .” A late novel, Tom’s Divine Comedy, is entirely devoted to the passage between one realm and the other.

|

|

On Wings of Song by Thomas M. Disch (Bantam Books, August 1980). Cover by Lou Feck

On Wings of Song is considered by many SF readers to be Disch’s finest novel, and — despite its notoriously unsuccessful first paperback printing, with its ill-advised cover and a 90% return rate — it was well-received in the genre, winning an award and eventually going through numerous editions. Its composition was, however, something of a career disaster for Disch. In the mid-seventies, when he wrote it, he was being published by Alfred A. Knopf, which had had a success with his witty Victorian melodrama Clara Reeve and gone on to publish Getting into Death, with other novels under contract. When he turned in On Wings of Song, however, Knopf rejected it. Disch bitterly broke with them, cancelling his outstanding book contracts (The Pressure of Time, which Knopf had advertised, would never be completed), and sending On Wings of Song on a long and galling tour of America’s most prestigious literary publishers, which all turned down the completed manuscript before Bantam and St. Martin’s Press put together a hard-soft deal. Although Scribner’s published Disch’s other serious historical novel, Neighboring Lives (written in collaboration with Charles Naylor) two years later, he felt that writing his best work, and doing it as science fiction, had thrown him back into the genre ghetto. (The Brave Little Toaster, also written during this period, endured its own years-long period of rejection by book publishers.)

The Businessman: A Tale of Terror was published by Harper & Row in the summer of 1984, and received glowing early reviews from Time and Newsweek. The New York Times Book Review wielded more influence than either, however, and its editors, astonishingly, assigned Disch’s book to Marion Zimmer Bradley, who declared her conviction that “self-consciously literary science fiction is a singularly distasteful version of what was called, a few years ago, ‘high camp’.” Because, she said, “Horror fiction is, let’s face it, an entertainment genre. It should be taken on its own terms,” any aspirations to artistic excellence should be reprehended. “It’s difficult to acquit Mr. Disch of the sin of writing with one eye on the literary critic and the other on the syllabus of the ‘modern fiction’ courses in college classrooms.” The hardcover did poorly, and when it sold in paperback for what Disch considered a humiliating sum, he bought back the rights and let it go out of print in this country.

|

|

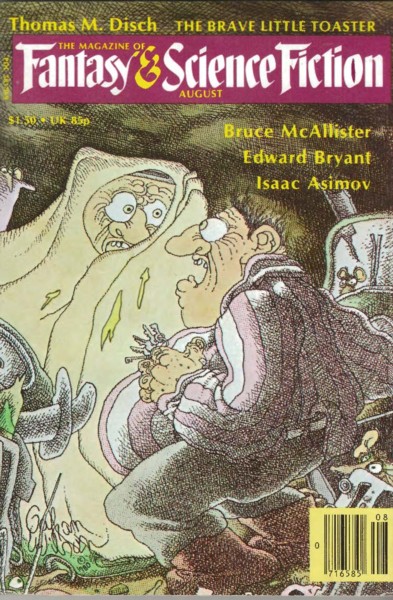

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, August 1980, containing

“The Brave Little Toaster,” and the 1987 film Disney version. F&SF cover by Gahan Wilson

Despite this, the 1980s — Disch’s own forties — was a fruitful decade for him: The Brave Little Toaster, after appearing in F&SF, was published in hard covers to acclaim and was made (along with its sequel) into a Disney animated feature; he published five volumes of poetry, wrote an interactive computer game, Amnesia, and saw small-scale productions of several plays and opera libretti. While he continued to publish short fiction in SF magazines and anthologies, Thomas M. Disch seemed to have completed the shift from genre to literary mainstream.

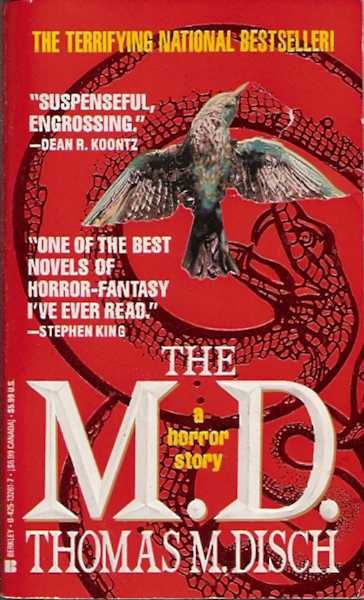

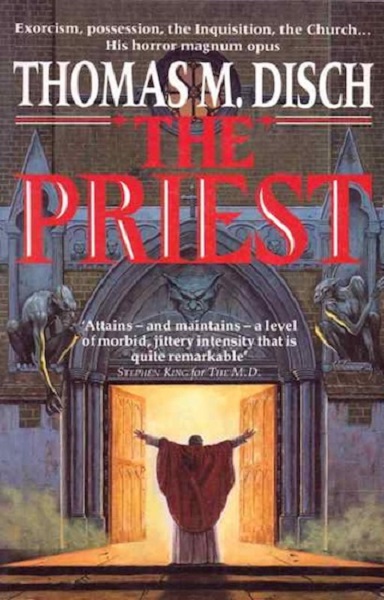

The limited accuracy of this perception became clear with the publication of The M.D., which (after editorial differences following its delivery to Dial and another multi-book contract cancelled) Disch’s agent was able to sell to Knopf. Published in 1991, the book was one of Disch’s longest: a mordant and sharply observed tale of the present and near future, handsomely produced and bearing laudatory blurbs by Stephen King and Dean Koontz. Despite these harbingers of good fortune, it received mixed reviews, and initial sales were again disappointing. A brilliant sales campaign by Berkley, however, made the book a bestseller in paperback, and Disch enjoyed popular success at last. The Businessman made a belated but triumphant appearance in paperback, rights to The M.D. and its successor, The Priest: A Gothic Romance were sold around the world, and Disch sold a fourth novel in the sequence for a huge sum.

Amnesia computer game by Thomas M. Disch. Published by Electronic Arts, 1986

The early nineties may have been the happiest years of Disch’s life. He bought a house in rural New York State, where he and Naylor spent several months of the year. He published a study of contemporary poetry, The Castle of Indolence: on Poetry, Poets and Poetasters, which was nominated for the National Book Award. His own poetry won an award from The American Academy of Arts and Letters, and his verse drama “The Cardinal Detoxes” was presented by the RAPP Arts Center in New York, where it caused a controversy after the theatre’s landlord, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York, sought to close the production. This proved the sort of publicity you couldn’t hope to purchase, and the ensuing legal wrangle — pitting freedom of expression against a clause in the Arts Center’s lease forbidding it to put on works that offended the “religious, moral and ethical principles” of the Archdiocese — was played out in the New York press for months. When the published work was reprinted in Best American Poetry 1994, Disch gleefully recounted its entire history.

If Disch seemed to be enjoying the best of both worlds — a contemporary horror novel becoming a mass market bestseller even as literary journals published his poems and essays and Neighboring Lives got its own belated paperback edition from the Johns Hopkins University Press — it was not to last. Despite the paperback sales of the first volumes of what Disch called “a sort of Balzacian comédie humaine, with overlapping characters,” The Priest — a dark fantasy that constitutes a scathing attack on the Catholic Church for its toleration of pedophiles in the priesthood — sold poorly in its U.S. hardcover and did not appear in paperback at all. It is the only case I know of a bestselling novel generating a successor that failed to sell to paperback. When The Sub suffered the same reception a few years later, Disch and Knopf parted company once more, this time at the publisher’s behest.

|

|

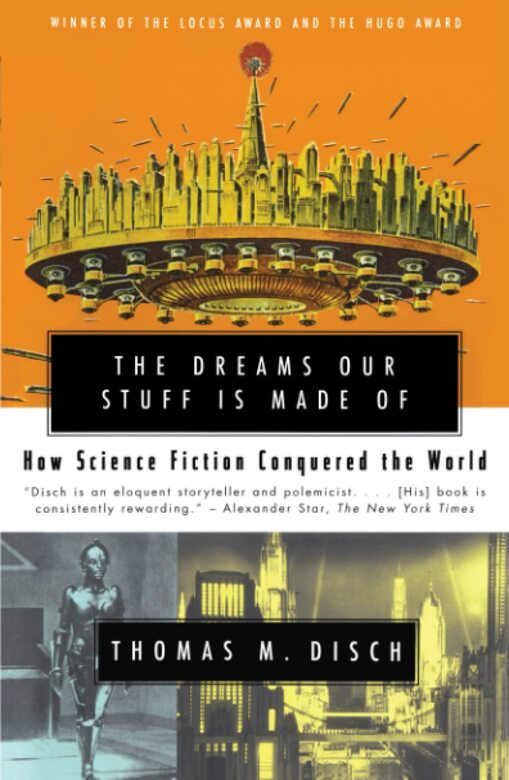

The Dreams Our Stuff is Made of by Thomas M. Disch (Simon & Schuster, July 2000)

It was the end of Disch’s career in trade publishing. He had won widespread praise in 1998 for The Dreams Our Stuff is Made of: How Science Fiction Conquered the World, a witty history of SF’s influence on popular culture, but the book had not sold well enough to earn out its substantial advance, and it became clear that whatever his critical reputation and however enthusiastic his core audience, Disch never sold in hardcover beyond the high four figures. As one publisher told Disch’s agent, “If Knopf can’t sell him, who can?”

Disch continued to write throughout his life, and in the first years of the new century he worked on several novels, including an SF novel, another Minnesota fantasy (which his agent wished Disch would permit him to market as a standalone), a contemporary work, and a few which resist categorization. Reluctant to complete any without a publisher’s commitment, he finished only one, Tom’s Divine Comedy, very different in tone and setting from the plot-driven, realistically textured novels of contemporary Minnesota. It did not find a publisher in his lifetime.

While he landed a large contract for another nonfiction volume, The Folly of Now: from Shock to Schlock, Disch found that his heart truly lay in imaginative writing. His insistence in proceeding in the face of repeated discouragement was no surprise to friends, who had known these twin aspects of his character — stubbornness to the point of seeming perversity, and an unflagging fertility of invention — throughout his career.

The true calamity came with the death of his longtime partner, Charles Naylor. After an illness of several years, Naylor died in 2005, and Disch — himself no longer in good health — was devastated. After that, disasters seemed to follow in rapid succession: Disch and Naylor had spent a final summer in the country, and soon after Naylor’s death Disch’s landlord began eviction proceedings, charging that the apartment where he and Naylor had lived from the mid-seventies was no longer Disch’s primary residence. The country house, closed up for the winter, suffered a frozen and burst water pipe, causing mold to spread behind its closed doors, destroying half the interior. Alone, bereaved, and feeling that he was being driven from his home, Disch grew profoundly depressed, and spoke often to friends of suicide.

Despite this, incredibly, he continued to write, and the sequence of poems that emerged from his grief, Winter Journey, is certainly his best. Disch rarely left his apartment save to visit the open-air market across the street in Union Square — sciatica and knee problems made it impossible for him to descend steps except backward, taking half-steps with his cane — but he discovered the Internet, and began a LiveJournal blog entitled Endzone. He communicated freely with readers he had never known, posted a large amount of poetry (some quite good), and commented on social issues of the day.

|

|

Clara Reeve by Thomas M. Disch (as Leonie Hargrave). Ballantine Books, July 1976. Cover artist unknown

It was this that drew much attention in the last years of Disch’s life, although friends (and attentive readers) had noticed it for some time. Beneath the urbane, smoothly ironic surface of his prose, Disch was a very personal writer, and the emergence of a strident new tone: an unlikely combination of suave cosmopolitan and cranky reactionary, whose aversion to — and sense of beleagurement by — illegal immigrants, Muslims, urban minorities, and most social activists was impossible to miss. The former columnist for The Nation began to write regularly for The Weekly Standard (where his editor ultimately rewarded him with a viciously demeaning obituary notice) and to regale friends with droll but uncharitable aperçus.

Part of this was not entirely new; Disch had always been more traditional in his aesthetics and his personal life than his life than his detractors noticed. The former Midwesterner who considered Thomas Mann his favorite writer and spent more than 35 years with the same lover — and who spent his life in quiet industry, working hard and living modestly even after he had earned (and saved) a small fortune — was sympathetic with the artistic avant garde and tolerant of life styles different from his own, but was never a social or political activist. That these sympathies hardened over time, then splintered under stress, is regrettable but not wholly surprising: except for a saintly few (Dorothy Day, or perhaps Grace Paley) radical sympathy for the disenfranchised — unfamiliar and perhaps unfriendly — grows harder to sustain as one ages, and pretexts for a withdrawal into self-interested insularity are always available. If Disch made this move more decisively, and with greater expressions of vehemence, than most, this can be ascribed both to aspects his personality — Disch had always possessed, beneath his urbanity and gravitas, a profound agitation of spirit, which manifested itself in hysterical and often self-destructive outbursts throughout his life — and to the extent of loss that he suffered. Only the saintly can open their hearts when their lives are collapsing upon them.

Nevertheless, Tom Disch was a man who felt the bonds of friendship and family deeply, and who elicited profound loyalty from those close to him. As far as I can tell, none of his closest friends shared, or had any patience for, his newfound political views; but nobody broke with him, even when he seemed to be baiting us. The cynicism and seeming impersonality that shines like a reflection in the high gloss of his work is in fact just that — a surface phenomenon, the first and most easily noticed, but one that is complexly and profoundly undermined by a closer engagement with the text.

Stories such as “Understanding Human Behavior,” “Slaves,” or “Concepts” — which moved Orson Scott Card to declare that if life were really as Disch portrayed it, he would kill himself — disclose, to keener readers than Card, the fourth compass point of Disch’s art, one that I hesitate to identify lest those who would appear wise gape and then snicker. It is, quite simply, the power of Love. The opposite of love is not hatred but fear, and when Disch was fearful his imaginative powers could only be turned to scorn. Never a writer to laud sincerity over artistry, Disch declined to declare his sentiments openly, insisting instead that readers make their own sense of his work. That such responsibility can be daunting — is The Brave Little Toaster satirical or heartwarming? If the author is an obvious atheist, then everything about God and Catholicism in The Businessman must simply be camp, right? — is clear enough, and the temptation of the easier reading is always strong.

|

|

Getting Into Death and Other Stories by Thomas M. Disch (Pocket Books, March 1977). Cover by Harry Bennett

But to know Disch’s work — or Disch himself — well was to see how deeply the themes of domesticity, connubial love that need not rely on constant stimulation of Eros, and the complex bonds of friendship informed his thought. It was the honesty of complexity that Disch insisted upon — of admitting the compelling case for an alien invasion succeeding; that people are generally self-serving, obtuse regarding their own motives, and think themselves smarter or more talented than they probably are. To acknowledge these truths is to run counter to the fatuous assurance of genre fiction, and to do so wittily rather than angrily or sorrowfully is to be regarded as all brilliance and no heart. In fact, Disch believed (but would disdain to say so in as many words, for that would be proffering a sop), you must concede as much about humanity in order to love it at all.

Vaughne Hansen of the Virginia Kidd Agency recently recalled that “the first time I met him, Tom struck me as a cross between a Hell’s Angel and a teddy bear. He was sitting at the foot of Virginia’s bed telling stories to her two small dogs. I think it was the story that became ‘The Happy Turnip.’ The dogs were spellbound and so were we.”

Adamant in all things, Disch was finally able to resume publishing books, this time in the flourishing world of the small press. (This was a source of profound satisfaction: “There are books in paradise,” says the poetess Adah Menken in The Businessman, “but no magazines.”) The Word of God, a surprisingly high-spirited novel written in the happy Christmas season of Charles Naylor’s last year, was published by Tachyon Press, which also brought out a late collection of his short fiction. The Anvil Press published a long poetry collection, About the Size of It, in 2007, with Winter Journey forthcoming from another house. [2022 Update: That publisher never issued the book, which remains unpublished.] Disch’s last novel was to comprise three novellas involving his own participation in the mythical voyage of the Proteus (more sailing to an edge), of which he only lived to complete two, available from the Subterranean Press. He still spoke of completing some of the novels he had begun half a dozen years earlier.

No one can say why it was that, with a book just published, another in galleys, and still more scheduled, Tom Disch took his life on 4 July 2008. His battle with his landlord had dragged on for years, but he stood in no danger of imminent eviction, and his country house was, after years of wrangling with insurers, finally under renovation.

John Clute has suggested that the act was a lifetime in the coming, the culmination of a deep conviction that affirming the right to end one’s life was only meaningful recourse into intolerable circumstances. Another friend, recalling that Disch had spoken of killing himself on the previous Halloween, suspects that the lure of an ironically fitting occasion helped tip the balance. His close friend Elsa Rush saw a sudden serenity in Tom’s behavior in the last week of his life, which the homicide detectives who handled his case had heard of before: the relief of one who has finally made up his mind. Others (like me) had noticed no such shift, and suspect a malign conjunction of circumstances, aggravated by diabetic mood swings. The lure of easy means (he had brought back a gun from the country) was always before him; if too many things hit a trough at the same time, he could act before reconsidering.

|

|

|

Disch’s horror novels: The Businessman (Berkley 1993), The M.D

(Berkley 1993), and The Priest (Millennium UK, 1994, cover by Les Edwards)

It is not going too far to say that Disch’s fiction holds two fields of focus: people, whom he observed closely, and the hereafter, which he obsessively imagined. When he wrote of people interacting, he produced brilliant social comedy; when he wrote of solitary individuals, as in “Descending,” “The Asian Shore,” or “Voices of the Kill,” he surrendered to his fascination with the transition between worldly existence and something else. But even the Minnesota novels — which are human-comedic enough to justify the comparison to Balzac — reflect this fascination, just like Mrs. Hansen’s resolution to commit suicide or Daniel Weinreb’s yearning to escape his body through flight. The beautiful vision at the end of The Businessman — of “a soul released from its cave of flesh” pausing briefly to tantalize some sleeping mind before departing this universe forever — suggests how powerful its allure was for Disch, and how strong, in his last days on Earth, its call must have been.

This essay first appeared in the SFWA Bulletin, Feb-March 2009 under the title “The Last Page of Thomas M. Disch.”

Interesting piece! Disch belonged to that shadowy pantheon of SF writers who produced work in the Sixties and early Seventies and who I knew by name but never read. I guess he’s an acquired taste? Reading ‘Camp Concentration’ on Amazon a few minutes ago, I kept thinking Kelsey Grammar would be a perfect fit for the audiobook. Make of that what you will.

I would definitely listen to a CAMP CONCENTRATION audiobook read by Kelsey Grammar. 🙂

I would not call Disch’s work an acquired taste any more than I would call the work of, say, Donald Barthelme or Franz Kafka and acquired taste. It’s more that it has powerful appeal to certain sorts of readers.

He was a fine novelist and a substantial poet, but one of the finest short story writers in English in the period 1965 – 2000 or so. And in the strange world called science fiction, Disch was in a fairly exclusive club of highly literate, fairly dark and ironical work. Delany once wrote that Disch’s approach could be called ‘skewed lyric,’ and there is something to what he said.

If you can find Disch’s stories “Angoulême,” “Bodies,” “Getting into Death,” and “The Asian Shore,” you will have some idea of what he could do. The first stories I read by him were “Descending,” “The Roaches,” “Casablanca,” and “The Number You Have Reached.” Those aren’t bad places to start, either.

A favorite of mine. I need to reread his novels and his short fiction. I just recently picked up a copy of Fundamental Disch and reread The Asian Shore, a favorite of mine.

[…] the Blackgate magazine website, they have posted Thomas M. Disch: Love and Non-Existence, a sensitive, insightful paean to Tom, penned by his friend Gregory Feeley. Originally written in […]

What a deeply insightful and encompassing retrospective on a complicated and compelling member of the sf/f community. Mr. Disch was a large talent in our field, and Mr. Feeley’s tribute to his friend is a welcome remembering for those of us who read him, and hopefully an enticement for those who have yet to have the pleasure.

Eugene — many thanks for linking to us from the BEAMER BOOKS website. I hadn’t realized you were a blogger! You should be writing articles for us. 🙂

I picked up The Castle of Indolence on impulse for a dollar from a used bookstore years ago. Through five moves, I considered putting it in the donation box, but held onto it. You just bumped it into my TBR list.

My understanding is that Mr. Feeley is the executor of Disch’s literary estate?

He mentions one finished, though, unpublished novel. There’s also THE TROLL OF SUREWOULD FOREST which was serialized in, I believe, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, but never published as a volume by itself. The stories that were written for THE PRESSURE OF TIME have never been collected. There are many works, such as “The Happy Turnip” and most of the stories published in Omni, that have never been collected. I suspect there’s one or two collections worth of hitherto unpublished/uncollected fictions.

Even a volume of his horror fiction; or his best stories (including works hitherto uncollected or those that make up some of the longer works) is long overdo.

But maybe, as when he was alive, the market just isn’t there for him?

Unfortunate. I hope something else eventually appears.

A Troll of Surewould Forest was serialized in Amazing Stories in 1992. It had been written in the mid-seventies, right after On Wings of Song. Nobody would publish it.

I am planning to scan in the published pages this fall and turn it over to the estate’s agent. Same with the existing sections of The Pressure of Time, which certainly deserve book publication.

A Selected Stories is also overdue, as is publication of his last and best volume of poems, Winter Journey.

Mr. Feeley,

I’ve followed all the Disch interviews and the like that I’ve been able to; and yet, some of what you’ve written here and above is either entirely new information to me or somewhat contradicts/correction information that is out there — so I have to ask, are you working on a Disch biography?

No, I am not. I would be glad if somebody were. But I have been working for years–interspersed with many other projects–on a biography of James Blish, and I won’t have time for both.

I hope that your efforts on behalf of The Pressure of Time and A Troll of Surewould Forest manage to get these works into print. I’ve got a few of the stories that make up The Pressure of Time, but Disch teased us with this book since back in the 1970s. As for A Troll of Surewould Forest, when it was serialised, I thought it would make it into print soon thereafter. But here we are 31 years later and still no book.

Good luck. And that last volume of poems is definitely something devoted long-time readers would like to have.

I’ve been reading Disch’s work since 1966. I miss his unique voice in fiction and essays.

A Collected Short Stories would be a nice, also, but at this point we’ll take what we can get.

I have one issue of the serialized version (in Amazing Stories, as Gregory notes) but haven’t yet found the other.

I add my praise for this lovely piece (which I read on its original appearance) — I’m very happy to see it reprinted here.

A lovely post, compelling me to seek out more of Disch’s work. Thank you for taking the time to write it.

Thank you for an interesting post. Recently I have translated a short story “Fun with your new head” into Japanese. Disch is still loved by SF funs in Japan.