Haunted Trains and the Rock-and-Roll Afterlife: The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series X, edited by Karl Edward Wagner

|

|

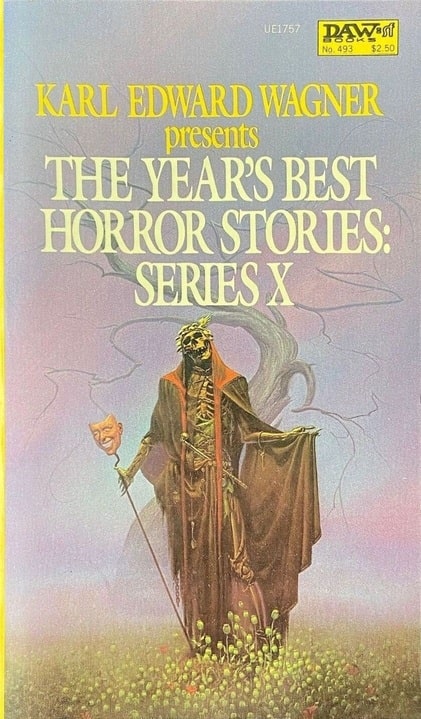

The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series X (DAW, August 1982). Cover by Michael Whelan

The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series X was the tenth volume in DAW’s Year’s Best Horror Stories, copyrighted and printed in 1982. A whole decade for this anthology thus far! This was the third volume edited by horror author and editor Karl Edward Wagner (1945–1994). Michael Whelan’s (1950–) artwork appears for an eighth time in a row on the cover. This is one of his eeriest and best yet. The same cover would later appear on the 1989 omnibus Horrorstory: Volume Five, a collection of volumes XIII-XV of this series from Underwood Miller.

Of the eighteen different authors in The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series X, all but two were male, with one story cowritten by a male/female team. (G. W. Perriwils is the pen name for Georgette Perry & William J. Wilson.) Eleven were American, the other seven were British. Of the fifteen stories included seven were from professional magazines, four from books, three from fanzines or booklets, and one was original to this anthology, though was to appear shortly afterward in another periodical.

I enjoyed the first volumes in DAW’s Year’s Best Horror Stories edited by Richard Davis (Series I–III) and Gerald Page (Series IV–VII). I would not say that these editors were “stale,” but Wagner does seem to bring a fresher vitality. I think this is due primarily to his introductions, which operate more as “state of horror field” yearly addresses, and his short bios before each story. I’m sure all good editors put forth their best efforts, but Wagner’s passion, I think, really shows itself in these volumes.

[Click the images for more horrifying versions.]

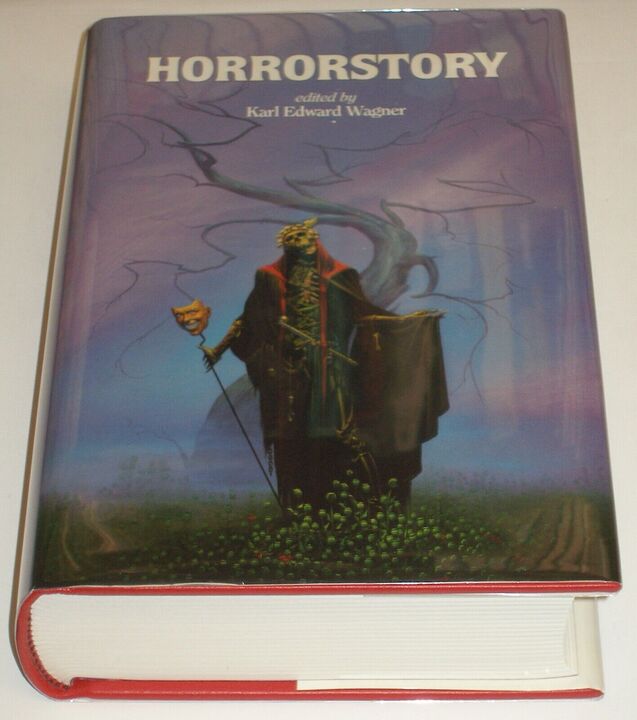

Horrorstory: Volume Five, an omnibus of

volumes XIII-XV of Year’s Best Horror Stories (Underwood-Miller, 1989)

The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series X is a continuation of the streak of excellent DAW horror collections. This volume contains some memorable horror tales that should not be forgotten. Let me highlight a few and then give my favorites at the end.

“Touring” was tri-authored by Gardner Dozois, Jack Dann and Michael Swanwick. The late Dozois (1947–2018) was a tour de force editor and writer in the field. His name graces the covers of many anthologies. And I was also familiar with Swanwick’s reputation as a writer, though I was not familiar with Dann. “Touring” is an interesting tale speculating on the afterlife of rock-n-roll legends like Buddy Holly, The Big Bopper, Janis Joplin, and, of course, “the king” Elvis Presley. Not really a horror story but more like an enjoyable Twilight Zone episode.

“Every Time You Say I Love You” is another horror homerun by Charles Grant. I always look forward to reading a Grant story. He is an excellent writer, even when his stories aren’t really all that horrific. This tale fit that bill . . . until the end, a surprising punch gut. And when I read the last page, I changed my mind completely: this was indeed a horror story!

|

|

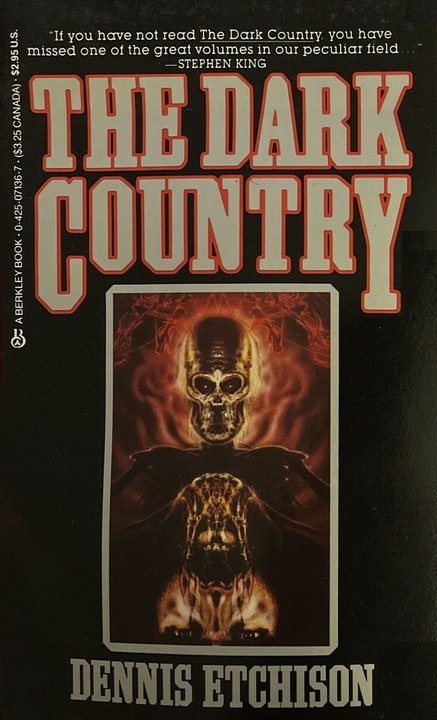

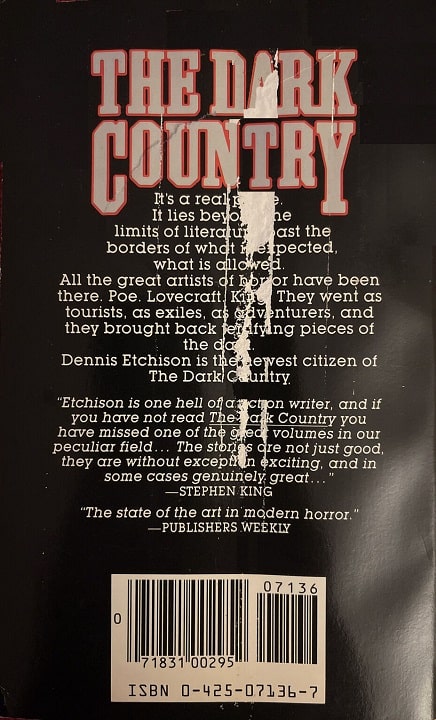

The Dark Country (Berkley Books paperback reprint, September 1984). Cover uncredited

Dennis Etchison’s “The Dark Country” (later the title of his 1982 collection) was an interesting read more in the vein of an absurdist tale. I generally don’t like this kind of “horror.” But if you’re in to Kafka, Ligotti, Borges, or Nabokov, Etchison scratches that itch.

Howard Goldsmith’s “Homecoming” was a predictable and on-the-nose pulp tale. It felt more like a television episode in R. L. Stine Goosebumps series. Sometimes I find it surprising that Wagner includes such stories. You get a sense that they reminded him of his youthful pulp reading and he included them for nostalgia’s sake. Not a bad story, though not incredibly scary.

My second favorite story in this volume was “Egnaro” by M. John Harrison. It’s very hard to describe. It focuses on a young man (teenager? twenty-something?) who works at something like a “dead head” shop. I don’t know if these exist anymore. They sort of went main stream when Spencer’s began popping up in malls back in the 1980s (though really not the same thing). There were usually in out of the way places and sold things like records (later 8-tracks and cassettes), black-light posters, band posters, smoking “paraphernalia,” incense, and non-mainstream literature. These shops tended to have a forbidden or “anti-establishment” vibe, which always made them alluring.

The main character describes it as an out of the way “shabby bookshop” owned by a hippy holdover named Lucas. Lucas pays only in cash (i.e., “off the books”) and sells books by authors like Crowley and Castaneda. The whole shop seems seedy and intriguing where the owner “made no distinction between pornography and science fiction” (p. 182). As Lucas cynically notes:

“It all seems the same to me,” he maintained. “Comfort and dreams. It all rots your brains.” Then, reflectively: “Give them what they want and take the money” (p. 182).

The story begins to get really interesting as Lucas starts to hint to our protagonist of a mythical concept called “Egnaro.”

Egnaro is a secret known to everyone but yourself.

It is a distant country, or some city to which you have never been; it is an unknown language. At the same time it is like being cuckolded, or plotted against. It is a part of the universe of events which will never wholly reveal itself to you: a conspiracy the barest outline of which, once visible, will gall you forever.

It is in conversations not your own (so I learnt from Lucas) that you first hear of Egnaro, and in situations peripheral to your real life. Egnaro reveals itself in minutiae, in that great and very real part of our lives when we are doing nothing important (p. 180).

So, what is Egnaro? The story never answers that question. It is a bizarre and perplexing tale. It hints at melancholy throughout as if life holds some big promise or secret we are never allowed to grasp, like a starving man looking for an impregnable fortress of wonderful food.

As the story progresses, Lucas’s fortunes digress more and more, slowly dragging down the protagonist’s life and outlook into the depressing depths with him. The story ends:

Wherever I am I think about it: whatever I do is tainted by it: but if you were to ask me what Egnaro is I could give you no answer. In my most despairing moments I believe that the human race exists solely to give it expression. No-one, I suspect, can have any clear understanding of it. All events are its signature: none are. It does not exist: yet it is quite real. The secret is meaningless before you know it: and, judging by what has happened to Lucas, worthless when you do. If Egnaro is the substrate of mystery which underlies all daily life, then the reciprocal is true, and it is the exact dead point of ordinariness which lies beneath every mystery (pgs. 201–202).

Is this just gobbledygook? Or is there some fearsome and terrible reality the protagonist and Lucas are on to? Impossible to say. But the tale radiates a creepy foreboding throughout. “Egnaro” greatly reminded me of Robert Chambers’s “Repairer of Reputations,” which has a Lucas-like character who is either crazy or connected to terrifying truths. “Egnaro” was not really a horror story, but it stays with you long after you read it.

But my favorite story in The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series X was “Mind” by Les Freeman. The setup is fairly simple. The main character Derek takes a train ride to the British seaside town of Whitby. After spending the day, he attempts to ride home. Unfortunately, the train seems stuck in a time loop because he continually arrives at Whitby again and again, with the same scenes unfolding at the train station every time.

I think the experience of being stuck in a time loop would be quite horrific by itself. But that is not the primary horror communicated here. Rather, his focus upon a family that he continually sees every time the train stops in Whitby becomes the real source of terror. When he first sees them:

On the platform Derek noticed a small huddle of children and a man. The man was about thirty-five to forty and the children — three girls and a boy — ranged in age from about four to twelve years. They were all well dressed and apparently well-behaved — until the train started to pull out of the station. As it did so, the youngest of the children, a little girl . . . exchanged her smile for a frown and screamed. . . . within seconds all four of them seemed to be wailing and crying and demanding the return of their mother who, Derek imagined, had boarded the train and was leaving the rest of the family behind (p. 153).

This seems like a typical parting of small children from their mother who is going away on a short trip, though the screaming seems a bit excessive. But as the time loop (for lack of a better phrase) becomes apparent to Derek, the scene becomes different and more frightening, as the children’s screaming becomes louder.

On Derek’s third return to Whitby he decides to get off the train and strikes up a conversation with a porter who relates how the previous year the local Martin family had met tragedy. The mother had left Whitby on a train for a short visit. The father drove the children home and had an accident that killed the whole family. When Mrs. Martin was told of the tragedy, she went mad. At the asylum all she kept doing was “saying goodbye to the children on the railway station, and then she hears them screaming and screaming” (p. 157).

Derek, for some reason, talks himself into getting back on the train, hoping that he simply had fallen asleep and had a nightmare that coincided with the Martin family tragedy. But such is not the case. The train’s fourth return to Whitby:

This time there was something unnatural about the four youngsters: they seemed to be grotesque plastic models, nothing real at all, with glycerin tears . . . . It was an awful tableau that was infinitely more frightening . . . . As he drew abreast of the group, all the faces turned in his direction, pressed their plastic noses against the moving window and screamed with horror directly at him, celebrating the fear they were creating in him. He drew back and covered his eyes as the train pulled out . . . . (p. 158).

His fifth return:

The screaming, which now seemed to be with him all the time, was harsher and louder and more deliberate — except for a brief spell when the train passed the group on the way out of the station, and all five of them turned to face him and, instead of crying out, they all laughed, their lips twisting into ghastly grins and grimaces as he shrank away from them (pgs. 158–159).

The title of the story “Mind” comes from Derek somehow coming to the conclusion that he is not in a time loop but locked in the insane mind of Mrs. Martin. I never got that impression from the story myself, but these scenes were unsettling and produced quite a chilling effect. I highly enjoyed Les Freeman’s “Mind.”

This was another excellent collection under Wagner’s editorship. Here’s the complete Table of Contents.

Introduction: A Decade of Fear, by Karl Edward Wagner

“Through the Walls” (British Fantasy Society Booklet #5, 1981) by Ramsey Campbell

“Touring” (Penthouse April, 1981) by Gardner Dozois, Jack Dann and Michael Swanwick

“Every Time I Say I Love You” (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction May, 1981) by Charles L. Grant

“Wyntours” (Original) by David G. Rowlands

“The Dark Country” (Fantasy Tales, 1981) by Dennis Etchison

“Homecoming” (Chillers July, 1981) by Howard Goldsmith

“Old Hobby Horse” (Ghosts & Scholars 3, 1981) by A. F. Kidd

“Firstborn” (Whispers III, 1981) by David Campton

“Luna” (Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone Magazine July, 1981) by G. W. Perriwils

“Mind” (New Tales of Terror, 1980) by Les Freeman

“Competition” (Running Times June, 1981) by David Clayton Carrad

“Egnaro” (Winter Tales 27, 1981) by M. John Harrison

“On 202” (Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone Magazine Dec., 1981) by Jeff Hecht

“The Trick” (Weird Tales #2, 1980) by Ramsey Campbell

“Broken Glass” (Gallery June, 1981) by Harlan Ellison

Previous installments in this series include:

Introduction To DAW Books’ The Year’s Best Horror Stories (1972–1994)

The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series I (1972)

The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series II (1974)

The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series III (1975)

The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series IV (1976)

The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series V (1977)

The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series VI (1978)

The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series VII (1979)

The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series VIII (1980)

The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series IX (1981)