Carving Out Destiny: Stormbringer by Michael Moorcock

There came a time when the destiny of Men and Gods was hammered out upon the forge of Fate, when monstrous wars were brewed and mighty deeds were designed. And there rose up in this time, which was called the Age of the Young Kingdoms, heroes. Greatest of these heroes was a doom-driven adventurer who bore a crooning runeblade that he loathed.

His name was Elric of Melniboné…from the Prologue to Stormbringer

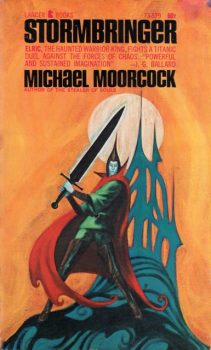

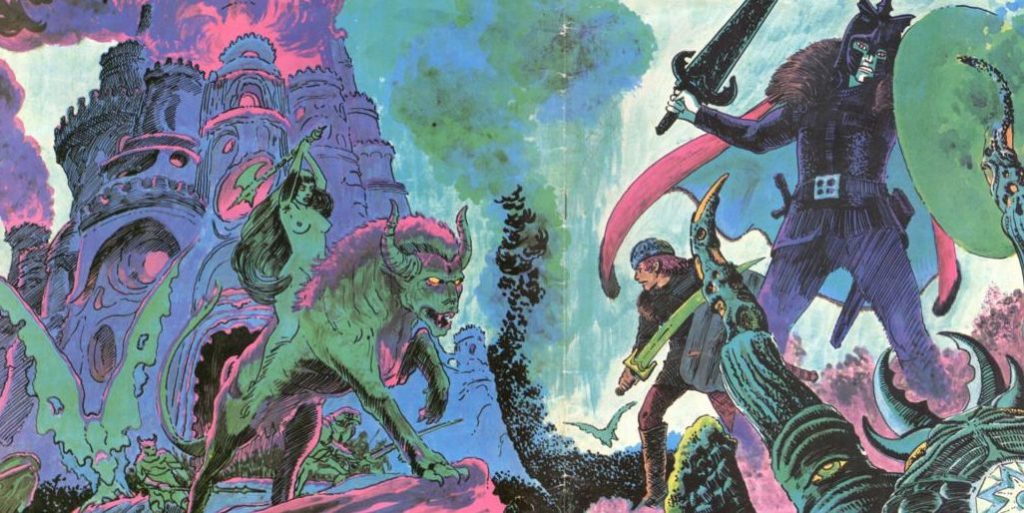

⇐ That cover, more than any other, depicts the absolute coolness of swords & sorcery and what I like about it. Michael Whelan’s painting for the 1977 DAW edition of Michael Moorcock’s Stormbringer (1965) is the first time in over two hundred essays I haven’t put the first edition cover first. You can talk about heroism, barbarism vs. civilization and whatnot until the end of the day but, ultimately, this is what I dig. That depiction of Elric, runeblade held high, Horn of Fate trailing behind him, under the storm-wracked heavens, says more about what brings me back to the genre than any book-long disquisition ever could. It’s just so stinking cool. Its appeal is purely and mind-blowingly visceral.

When I was in my mid-teens, all my friends and I devoured these books relentlessly. As soon as one of us finished one series we plunged right into the next. The gradual realization that all of Moorcock’s S&S stories were linked in some crazy pattern made our reading even more compulsive. Many, many elements in his books wound up in roleplaying sessions. I ended at least one universe in a very Moorcockian style.

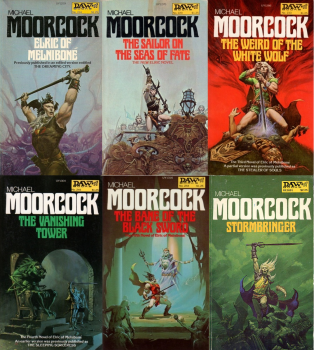

I did a quick count of how many Moorcock books I’ve read and got over thirty. Some of them, particularly the assorted Eternal Champion books (Elric, Dorian Hawkmoon, Corum, etc.), I’ve read numerous times. I’ve probably read all six Corum novels five or six times. I have definitely not reread any other S&S books, neither Robert E. Howard’s nor Karl Edward Wagner’s, anywhere near that number of times. Moorcock’s books have done more than any other’s to build the framework of what S&S writing is for me if by no other measure than number of pages read. There’s more creativity when it comes to characters and world-building in almost any of his slim DAW yellow-spine books than nearly any monstrous tome I’ve bludgeoned my way through.

And yet somehow, in the last twenty years the only Moorcock book I’ve read is The Eternal Champion (1970). I reviewed it for Black Gate (HERE) and I didn’t really like it. I think I enjoyed it when I read it the first time, back in the early eighties when I was devouring his books omnivorously, but I didn’t anymore. I found it too simplistic, the moral questions all being too black-and-white. It made me wonder if I’d lost my taste for Moorcock’s books; if I had just outgrown them. With my return to Stormbringer, I’ve been assured I haven’t.

Michael Moorcock (1939- ) is one of the most significant figures in fantasy and science fiction of all time. He began his literary career at the age of seventeen, editing Tarzan Adventures, a British magazine featuring stories and comics. In 1964 he became editor of New Worlds and helped forge the New Wave movement in speculative fiction. And at the same time, he was the single most important person reviving S&S.

He started writing stories as a teenager, releasing his own Sojan the Swordsman stories in Tarzan Adventures. He wrote a series of Edgar Rice Burroughs pastiches and other pulp-inspired stories in the early 1950s and ’60s. 1961 saw the arrival of Elric of Melniboné in the novella “The Dreaming City.” It started Elric’s story in media res, already in possession of the cursed sword, Stormbringer, and ready to rescue his beloved and destroy his homeland. As Moorcock wrote more S&S tales, he connected them, creating a vast Multiverse (a term which he created). Most of his protagonists are incarnations of the Eternal Champion, a figure destined to fight for the Cosmic Balance. The Balance is an unknowable force that works to maintain equilibrium between the forces of Law and Chaos that constantly battle for supremacy across the countless worlds of the Multiverse.

I came to Elric haphazardly. My dad had copies of the Lancer editions of The Dreaming City (1972) (which isn’t the same as the novella from 1961; the series’ publishing history gets complicated at times) and The Sleeping Sorceress (1971). These had been edited and issued without Moorcock’s permission. Later, they’d be rejiggered into Elric of Melniboné and The Vanishing Tower, the first and fourth books of the original six-volume series, and clearly, stuff was missing in between.

My friend Karl H. then started raving about Stormbringer, the concluding story in Elric’s saga. He raved about just how cool the book was and told me the last line of dialogue in the book which he recited with gleeful menace. I won’t tell you what it is, but to 12- or 13-year-old me it was awesome. Needless to say, when I did finally get Stormbringer, I devoured it at once and did, indeed, find it amazingly cool.

In the dedication, Moorcock describes Stormbringer as his first full-length novel, but it’s a fix-up of four previously printed stories: “Dead God’s Homecoming,” “Black Sword’s Brother,” “Sad Giant’s Shield,” and “Doomed Lord’s Passing.” I assume everything was rewritten somewhat in order to make it more cohesive, but in that regard the book never quite succeeds, feeling more like four separate stories than one single book.

Elric is an albino, sick and weak, maintained in life by potions and sorcery. He is the emperor of Melniboné, a nation of utterly amoral elf-like people who once upon a time ruled all the world, treating humans no better than animals. After ages of dominance, they have fallen into a decaying, indolent state and lost most of their empire to humanity. Elric, though, is drawn to the idea of morality and of achieving something more with his existence.

For ten thousand years the Sorcerer Emperors of Melniboné had ruled this world, a race without conscience or moral creed, unheedful of reasons for their acts of conquest, seeking no excuses for their natural malicious tendencies. But Elric, the last in the direct line of emperors, was not like them. He was capable of cruelty and malevolent sorcery, had little pity, yet could love and hate more violently than ever his ancestors. And these strong passions, perhaps, had been the cause of his breaking with his homeland and travelling the world to compare himself against these new men since he could find none in Melniboné who shared his feelings.

Elric has been moody, romantic, sometimes petulant, and given to raging against the Universe for its unfairness and indifference. In fact, he’s very much like a teenager, and I suspect that’s part of why my friends and I were drawn to these books. Elric is the embodiment of teenage anxiety and rage against the world that expects him to act a certain way and orders him about without any seeming concern for his own cares and wishes. That he’s bookish and weak, yet overcomes his enemies and usually gets the girl (except for his beloved Cymoril, but that’s another story), made him all the more appealing to the nerdy, D&D-playing crowd I belonged to. To be honest, it still kind of does.

Through a complicated series of events, he gains a patron in the demonic Chaos Lord, Arioch, acquires the soul-devouring Stormbringer, and destroys his kingdom, abetting the genocide of most of his race. Across the series, Elric, while ostensibly a servant of Chaos, is drafted into the ongoing efforts of the Cosmic Balance to maintain a balance between Law and Chaos. In this, his greatest tool is Stormbringer. It devours the souls of those it slays, siphoning off some of that energy for Elric, but it is also prone to sending him into a killing frenzy that leaves not only foes dead, but often friends and lovers as well.

By the beginning of Stormbringer, Elric is married, has locked away his evil sword, and hopes to spend his days at peace. Alas, in the first few pages, his wife, Zarozinia, is kidnapped by supernatural creatures. Attempting to discern the whos and whys of this deed, Elric learns that the forces of Chaos are marching. The human kingdom of Pan Tang, under the leadership of Theocrat Jagreen Lern, is attempting to bring all the world under the foul hands of Chaos. To rescue his wife and thwart the rising tide of Chaos, Elric must undertake a series of perilous quests and face an unending torrent of monstrous opponents. Everything Elric holds dear — his wife, his friends, his new home — is put at grave risk, and the world’s continued existence is in question.

Stormbringer doesn’t add depth to the characters — Elric is moody, Moonglum is buoyant, Jagreen Lern is sneering — we’ve gotten to know them well in the previous five volumes (Elric of Melniboné, The Sailor on the Seas of Fate, The Weird of the White Wolf, The Vanishing Tower, and The Bane of the Black Sword).

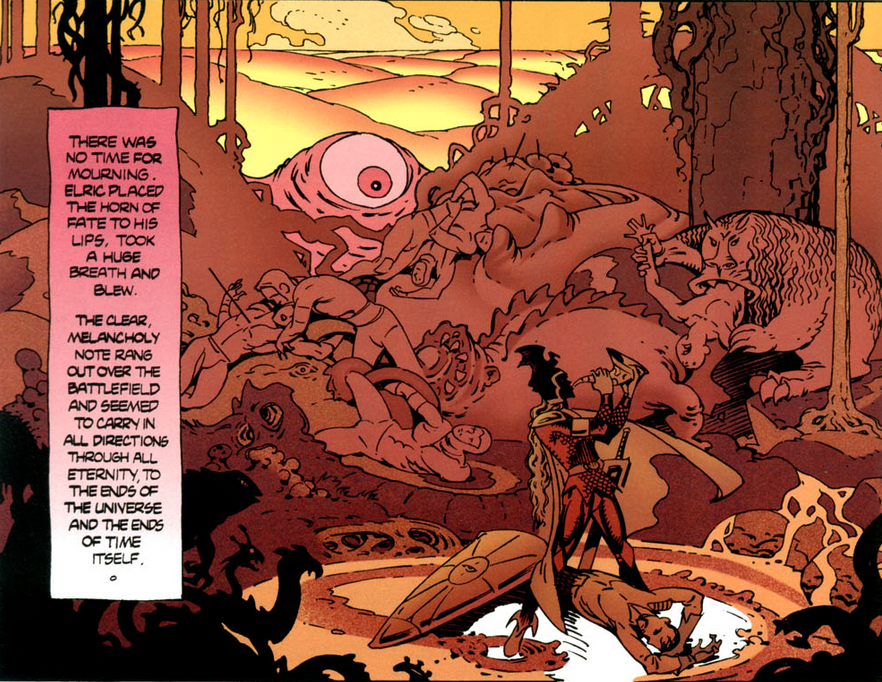

Stormbringer kicks right off and the action builds relentlessly, giving little space or time for the characters to develop. As the book is awash in Moorcock’s usual madcap inventiveness, I don’t care. Winged men fighting giant owls, ocean-towering ships crewed by the dead, demon lords with giant weapons, Chaos warping and twisting the very essence of reality, it’s all there. His descriptive passages are marvelous and it’s easy to see why several comic book artists have been drawn to this and other books of his over the decades.

Now, in the grey dawn, the two armies advance upon each other, coming from opposite ends of a wide valley, flanked by low, wooded, hills.

The army of Pan Tang and Dharijor moved, a tide of dark metal, up the shallow valley to meet them. Elric, still unarmored, watched as they approached, his horse stamping the turf. Dyvim Slorm, beside him, pointed and said: “Look — there are the plotters — Sarosto on the left and Jagreen Lern on the right!”

The leaders headed their army, banners of dark silk rustling above their helms. King Sarosto and his thin ally, aquiline Jagreen Lern in glowing scarlet armour that seem to be red-hot and may have been. On his helm was the Merman Crest of Pan Tang, for he claimed kinship with the sea-people. Sarosto’s armour was dull, murky yellow, emblazoned with the Star of Dharijor upon which was the Cleft Sword which history said was borne by Sarosto’s ancestor Atarn the City-Builder.

Behind them, instantly observable, came the Devil Riders of Pan Tang on their six-legged reptilian mounts, bred by sorcery it was said. Swarthy and with introspective expressions on their sharp faces, they carried long, curved sabres, naked at their belts. Prowling among them came over a hundred hunting tigers, trained like dogs, with tusklike teeth and claws that could rend a man to the bone with a single sweep. Beyond the rolling army as it moved towards them, Elric could see the tops of the mysterious cage-wagons. What weird beasts did they contain? he wondered.

As the story builds, the world becomes increasingly unmoored from reality as the forces of Chaos overrun each kingdom. Plants, animals, and humans, all are transformed into horrid and unstable forms. One of the great strands running through Moorcock’s Multiverse is the struggle between Law and Chaos, but it’s really about unfettered creativity vs. immovable order. Unchecked, the first leads to uncontrollable instability and the latter to absolute stagnation. Somewhere between the two great powers, a balance must be found. If there’s a philosophical core to the Elric books, that is it.

The book — and the series — comes to a world-shattering conclusion replete with flame-spitting dragons, nigh-endless killing, and the gods themselves in combat against each other. The final pages of Stormbringer are filled with moments of wild, almost psychedelic, intensity.

Both the Lords of Law and those of Chaos had become huge and misty as their earthly mass diminished and they continued to fight in human shape. They were like half-real giants, fighting everywhere now — on the land and above it. Far away on the rim of the horizon, he saw Donblas the Justice Maker engaged with Chardros the Reaper, their outlines flickering and spreading, the slim sword darting and the great scythe sweeping.

Unable to participate, unsure which side was winning, Elric and Moonglum watched as the intensity of the battle increased and, with it, the slow dissolution of the gods’ earthly manifestation. The fight was no longer merely on the Earth but seemed to be raging throughout all the planes of the cosmos and, as if in unison with this transformation, the Earth appeared to be losing its form, until Elric and Moonglum drifted in the mingled swirl of air, fire, earth and water.

The Earth dissolved — yet still the Lords of the Higher Worlds battled over it.

Reading with more of a critical eye than I thought I could bring to a book I’ve read many times over the years, I can see flaws in Stormbringer. It doesn’t feel like a unified novel, with events occurring suddenly and with little foreshadowing. Characters come and go and have thin personalities. Some of the stilted faux old-time dialogue is nails-on-chalkboard grating. Nonetheless, I can also see more clearly why I loved and still love Stormbringer.

The most important reason, which I’ve stated over and over, is it’s so effing cool. Moorcock seems to have been thoroughly unacquainted with restraint. For every monster, there are two more to come. The battles get bigger and crazier. More than all that, Elric himself has what I really want in a S&S protagonist — utter badassery in spades.

In the midst of Lord Xiombarg’s division, Elric landed again, dismounted from Flamefang and, possessed of his supernatural energy, rushed into the ranks of fiendish warriors, hewing about him, invulnerable to all but the strongest attack of Chaos. Vitality mounted and a kind of battle madness with it. Further and further into the ranks he sliced his way, until he saw Lord Ximobarg in his earthly guise of a slender, dark-haired woman. Elric knew that the woman’s shape was no indication of Xiombarg’s mighty strength, but without fear he leapt toward the Duke of Hell and stood before him, looking up at where he sat on his lion-headed, bull-bodied mount.

Xiombarg’s girl’s voice came sweetly to Elric’s ears. “Mortal, you have defied many Dukes of Hell and banished others back to the Higher Worlds. They call you godslayer now, so I’ve heard. Can you slay me?”

“You know that no mortal can slay one of the Lords of the Higher Worlds whether they be of Law or Chaos, Xiombarg — but he can, if equipped with sufficient power, destroy their earthly semblance and send them back to their own plane, never to return!”

“Can you do this to me?”

“Let us see!” Elric flung himself towards the Dark Lord.

Passages like that are why I love Stormbringer and Elric. The book is an utter blast, from start to finish.

Archaicisms aside, Moorcock’s writing is fast and sharp. His descriptive passages are indeed fantastic, but they’re also no longer than they need to be. Digressions are kept to a minimum. Everything is oriented to moving the story along at an ever-increasing pace and intensity. If you want forty-page speeches and chapter upon chapter of descriptions of food, Stormbringer and its predecessors are not for you. If you want quick, razor-sharp adventures instead, then they are definitely for you.

However, I can only recommend it under the right circumstance: you must have read the preceding novels, by which I mean the original six-book series. (Moorcock’s written several other books, but I found them less than essential). I’d say do yourself a big favor and track down the original DAW releases from the seventies. He’s had a habit of rewriting and re-editing his books over the years and I’m not sure it’s done them the great service he intended. Also, the Michael Whelan covers are WAY awesomer than any that have followed. The newer covers are washed out and artsy. It’s as if they’re trying to hide the fact that the books are about an albino sorcerer with a huge, evil sword that sucks out souls.

I’ve written before and I’ll write it again: I read S&S to escape the day-to-day world with its real responsibilities and burdens. I read it to escape into adventure and to see exotic realms through the eyes of someone more powerful and fearless than I am most days. There are those who dismiss this sort of writing as childish. I don’t have any time for those sorts of people. We need escape valves in our lives, be they sports, pasttimes, or pulp fiction. Michael Moorcock, pulp-fiction creator par excellence, has written dozens of tales that have imprinted indelible images on my brain, and I’ll be forever grateful for that. Now, I might go back to the very beginning myself with a reread of Elric of Melniboné.

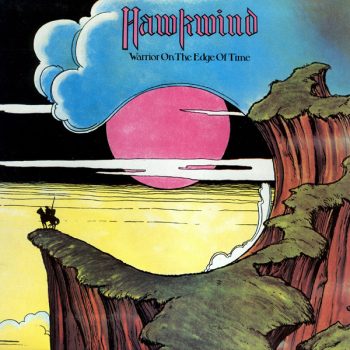

NOTE: Michael Moorcock has also been involved in rock ‘n’ roll from his youth, performing in various bands over the years. He became friends with the assorted characters of the foundational heavy psychedelic band Hawkwind back in the day and went on to collaborate with them numerous times. He wrote scads of lyrics for them and helped in the creation of the albums Warrior on the Edge of Time (1974) and The Chronicle of the Black Sword (1985), both inspired by Moorcock’s writings. He also wrote lyrics for several Blue Öyster Cult songs, including this epic slab of awesomeness:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xY8z0Avv12k

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

I have mixed emotions about Moorcock and his writing. I certainly devoured his Elric books as a teenager but they never meant as much to me as the work of Howard and Leiber. I also greatly dislike his hatred of Tolkien’s work. And yet I keep coming back to him. I guess like you say he is just cool.

I came to REH later and found some of Leiber dull. Yeah, his anti-Tolkien screed is poor

Leiber is really uneven as a writer. The early Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser stories were really good, but the later ones weren’t as good. The final story “Mouser Goes Below” was just awful.

I also came to Howard later, but I prefer him to Moorcock.

Moorcock’s criticisms of Tolkien is valid as far as I am concerned. There is little doubt that Tolkien’s world mirrors the class conscious society that existed in England at the time when the Lord of the Rings was written. (The Orcs talk and behave like chavs. I know, the word wasn’t in use at the time.)

Nor do I care much for Tolkien’s (mis)use of Norse Mythology. Its paganness is given a Christian varnish that ill suits the material. To me Gandalf will always be a pagan dwarf, and not a Christ-like wizard spouting inanities.

In other words, I rank Tolkien far below REH, CAS, KEW, Moorcock, Vance, Michael Shea, Tanith Lee, John Myers Myers, David Gemmell … I do rank him higher than Lin Carter though.

Moorcock and the adolescent me were a perfect fit. Now, maybe not so much. I did read a Moorcock novel a few weeks ago – The War Amongst the Angels – for the first time. I enjoyed it, but am not sure how many new readers it would attract.

I did garner a few insights over the last few years about his process. I’ve always enjoyed his anarchic approach to story-telling, but in fact he struggled with conventional narrative arcs and his inventiveness seems to have been an attempt to compensate for this. Increasingly I suspect he had a specific modus operandi as a pulp author. He took popular tropes and inverted them. I also reckon this is how some of his most famous creations came into being.

One reason this isn’t so obvious is because Moorcock translated and inverted contemporary literary tropes into a fantasy context. As somebody on this site pointed out a while back, Dorian Hawkmoon is a solitary German taking on the dark might of the ‘Gran Bretern’ (the wartime stories of the day would have featured a brave Englishman tackling the Nazis). Similarily, Elric is that old Wild West staple, the gunslinger who is nothing without his gun. And assuming the analogy is deliberate, Moorcock’s perspective is kind of interesting; Elric is pitiful rather than heroic.

Oh, yeah, his S&S novels, even when they aren’t, feel like fixups with the attendant choppiness and slapdashedness. He was definitely twisting the tropes; Elric’s the anti-Conan, the Oswald Bastables flip GA Henty imperialist storytelling, etc.

Absolutely.

Long gone are the glory days of the 70’s, when I read through the first three Corum books in three days, mostly in my high school classes. I’ve been returning to the Elric books myself recently – I just read The Sleeping Sorceress last month. What always strikes me most in these “classic” Moorcocks is how jerry-built the books are structurally and how slapdash the actual writing often is. I think Hawkmoon is the series least affected by these faults. I think Aonghus is right – MM’s black-light poster sturm und drang is best suited to one’s adolescent years.

For my money, Gloriana and Von Beck are Moorcock’s best fantasies.

The Hawkmoon books, written, I think, purely for the quick bucks, are pretty coherent and I think it’s due to being written in weekend-long spurts. They’re just one quick, continuous flow.

I do like the Robert Gould covers that followed the Whelan. (The first time I read Elric, I was borrowing my friend’s copies with the Whelan covers; when I bought my own shortly thereafter, the Gould were what was available.) And speaking of Whelan, if nothing else, the COVER of Elric at the End of Time deserves recognition.

Elric at the End of Time and Sailor on the Sea of Fate covers are tied for second place

Thanks for this post Fletcher. You really nailed it for us who fell in love with this book and the Elric series at the time. You perfectly captured their allure and magic, despite their faults. Moorcock was on something of a roll when he wrote these. I’m Joe H. My first reading of this series was with the Gould, not the Whelan covers (though I own those too now!). In fact, I have an original print of the Sailor on the Seas of Fate cover. Only fantasy artwork that I own. Thanks again for this post.

You’re welcome and thank you for the kind words. I am very jealous of your Whelan print.

Over the years, I have found the original Moorcock books (through Stormbringer – I’m not much of a fan after that) to be ones I go back and re-read every so often. I gobbled up Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser in my D&D youth, but haven’t been able to complete a re-read. I find them slow and eventually put them back on the shelf.

And I study and write about Tolkien more than I just sit and read him. But Elric, the first three Corums, sometimes Hawkmoon – I always enjoy them when I re-read them.

Unlike Lieber, Moorcock outlasted my adolescence. Though, as with the Sanctuary books by Aspirin and Abbey; and Glen Cook’s The Black Company, I usually have to take a break partway through. They’re too depressing.

I definitely think you have to pick and choose which Lieber stories to read. The core Eternal Champion books are just fantastic. And, what, you don’t like the second Corun set? 😁

And I don’t like the later books much, myself, though I do get a kick out of the story “Elric at the End of Time.”

Damn – Fritz is taking some licks here. I must say that I lean the other way; if I could only keep one writer, I would take Leiber over Moorcock, and much as I like Moorcock, it wouldn’t even be very close.

I do think that Leiber’s science fiction ( The Big Time, The Wanderer, A Pail of Air, Marianna) and his horror (Conjure Wife, Our Lady of Darkness, Smoke Ghost) is superior to his S&S.

I like those novels and was surprised how dull some of the Fafhrd/Grey Mouser stories are.

i gotta admit i tried Moorcock once back when i first started high school and it didnt click. now in my older years, i want to go through the catalogue but when i look at amazon i have NO CLUE where to start or what to read first, there are a ton of versions and different collections…

Original six Eric books (the Whelan covers shown above), original three Corum and original three Hawkmoon

Re Leiber. Maybe Matthew has a point? I checked out Leiber again recently (a collection of horror stories and a Fafhrd and Gray Mouser story) and found him pretty indigestible. But the S&S stories were written over a long time – as far as I can remember, anyhow – so some stories are bound to be better than others. Whatever about their quality, I do think Leiber created a pair of S&S characters that were dimensional, believable human beings – something of a first at the time.

They’re fantastic characters and the good stories are great, but even with them I’ve always detected a current of theatricality that undermines them to a degree

Thanks for that pure blast of nostalgia.

Personally, I think the fix up nature of the stories is a strength not a weakness. Fantasy novels are all too often an abomination in the sight of God and man.

In any case schoolboys just took what they could get, in any order, depending on availability in physical shops. All this which edition stuff is for old people.

You’re welcome. I’ve been riding my anti-doorstopper hobby horse for years. S&S works best in sharp, concentrated doses. There’s a good chance we did read these as much from easy availability as coolness.

Thanks for publishing this Fletcher, your words have been encouraging. The versions I have are the Grafton issues, circa 1990, also with cover art by Michael Whelan, although some pictures differ from the earlier DAW ones, with the exception of Stormbringer, which is the Mayflower Bob Haberfield version. I have had these books as well as both Corum series on my shelf for years but have always found an excuse not to read them. Possibly a fear of disappointment, which i experienced with the Oswald Bastable series. Following your recommendation, perhaps the time has indeed come that i take the leap and binge read my way through the series.