IMHO: A PERSONAL HISTORY OF SWORD & SORCERY AND HEROIC FANTASY

The Evolving and Cloned Barbarian

Conan, King Kull, Cormac, Bran Mak Morn — names that conjure magic, characters often imitated, but never duplicated. These creations of Robert E. Howard (circa 1930) started the Sword and Sorcery boom of the 1960s and early 1970s. Then there are the barbarian warriors inspired by Howard — “Clonans,” as one writer recently referred to these sword-slinging, muscle-bound characters. A fair observation, but in some cases, not so true.

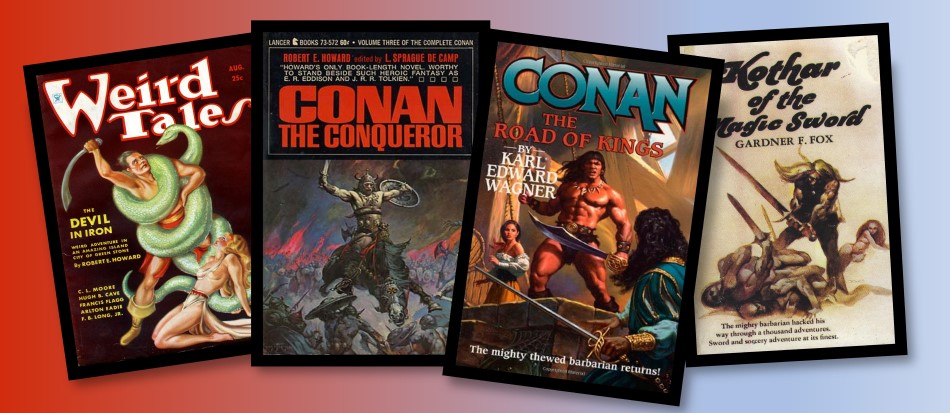

I prefer to think of these “Clonan” tales of wandering barbarian heroes as “Barbarian Solo” adventures because the majority of these characters are lone wolves, without sidekicks or even recurring companions. This is a big part of their appeal, in fact, and in their own way, they are reminiscent of many cinematic westerns. I’ve read many, if not most, of the early Conan pastiches, including the novels based on Howard’s other creations. Karl Edward Wagner’s, Poul Anderson’s, and Andy Offutt’s portrayals of the Cimmerian come within a sword’s stroke of Howard’s original vision. L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter, in commodifying the character, arranged the long, informal saga of Conan in chronological order and, by extenuating these adventures with dozens more, made of Howard’s creation a long-form series similar to the episodic success of a television show on a prolonged run of diminishing returns. For some readers, however, the advantage of this development is that it provided a sort of character arc as Conan grows from a youth to an older man.

That said, however, it is better to read the Conan tales in the order in which Howard wrote them. By doing this, we gain at least two things: the sense of an adventurer’s life being recounted in the same haphazard way that it was lived, and — perhaps more importantly — we witness Howard’s own developing arc as a writer — his growth, his maturity, his mastery of the art of storytelling. We also get to watch as Howard becomes more sharply attuned to his markets, as Conan the commercial property evolves from the regal lion of “The Phoenix on the Sword” and the dangerous young buck of “The Tower of the Elephant” to his later portrayals as a lusty roustabout and badass, soldiering and womanizing, carousing and drinking, fighting and fighting some more — and, more often than not, attaining that month’s Weird Tales cover with a Margaret Brundage beauty in bondage. But the endless parade of pastiches shares much of the blame for the death of the Barbarian Solo craze of the late 1960s, 1970s, and early 1980s.

In addition, in a period of historic social change, many of these tales betrayed an attitude that was falling out of favor. The limitations apparent in this go-round of Sword and Sorcery fiction were not challenged, and most of the pastiches predictably moved along a preordained path with a one-dimensional, exaggeratedly masculine character going through rote episodes no more compelling than the umpteenth rerun of a grade-C, TV show. Furthermore, the audience for these stories grew older and turned to other distractions. The demise of the one-dimensional, muscle-bound hero at that historical moment was deserved. True story: in 1970, I wrote a letter to Lin Carter, who was then the editor of Ballantine Books’ Adult Fantasy Series. I asked how to go about submitting a Conan novel I had written. Lin Carter was nice enough to reply quickly, telling me that only he and L. Sprague de Camp were licensed to write Conan stories. He suggested, however, that I change the name of Conan to one of my own choosing and change any other names borrowed from Howard, then submit the novel to a publisher as my own original creation. (A high school friend believes he still has that letter, packed somewhere in his garage: I had sent it to him, but he failed to return it to me. Hopefully, he will find it one day.)

In Other Words, I Was Advised to Write a “Clonan” Novel

In my humble opinion, this was a disgraceful attitude, basically telling me that Conan was interchangeable with other barbarian heroes. This, I did not care for. I had no interest in creating my own barbarian warrior: we already had Jakes’ Brak, Gardner Fox’s Kothar, and Lin Carter’s Thongor, to name three. I wanted to write a Conan novel, by Crom! Oddly enough, it was shortly after this response from Lin Carter that Bjorn Nyberg’s Conan pastiche appeared on the scene. Then, as we know, other writers were brought in as “hired guns” to continue the Conan saga — and, as so often happens in the wake of hired guns, there was trouble…

We Saw the Slow Death of the Barbarian Solo Brand of Sword and Sorcery

The first huge wave of the Sword and Sorcery boom was actually rather short-lived. It lasted from roughly the mid-1960s to around the early 1980s. It gave us a roster of new and wonderful talents such as David C. Smith, Janet Morris and Chris Morris, Ted (T. C.) Rypel, Richard L. Tierney, and David Drake. And let us not forget the late David Madison, Dave Mason, Charles Saunders, Karl Edward Wagner, and Tanith Lee. These diverse writers all worked hard to rethink and reshape the Heroic Fantasy and Sword & Sorcery genres into something grand, thoughtful and introspective, returning us to the roots of literary, as well as historical fantasy. After that, as the popularity and success of epic fantasy spawned numerous series of multi-volume sagas, the old-school brand of sword and sorcery all but disappeared. Many publishers began to shy away from the “barbarian thing,” the kind of Sword and Sorcery on which many of us cut our teeth.

As most of us who were alive in the 1950s and 1960s know, it was JRR Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings that became the game-changer. LOTR became an astounding cult classic, and its success encouraged Ian Ballantine to launch the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series in the late 1960s, bringing back into print such authors as Lord Dunsany, George MacDonald, William Morris, Evangeline Walton, E.R. Eddison, James Branch Cabell, and Mervyn Peake, among others. Of all the other sword and sorcery novels of barbarian warriors who followed on the heels of Conan’s success, only the Conan the Barbarian series caught and hung on, however. Associated works, such as Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser series, and Michael Moorcock’s Elric series, to name two, also rode the crest. Barbarian fantasy still sold, and it was the conventional wisdom that it sold only to teenage readers, not to the wider Tolkien audience. But Fritz Leiber and Michael Moorcock were not writing about muscle-bound characters, and for me they were the first of the “stand-outs” I read in, as Lin Carter dubbed it, “The Sacred Genre.” (On a more personal note, it was Leiber and, oddly enough, Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett who finally inspired me to write the type of fantasy I now write.)

Tolkien Influences All Sorts of Fantasy

Sometime around 1977 Ballantine found a way to reach the Tolkien readers when Lester del Rey, then a consulting editor for the publisher, read the manuscript of The Sword of Shannara, by Terry Brooks. Following the success of Brooks’ fantasy novel, del Rey founded his own fantasy imprint and moved forward with his line of written-to-order, mass-marketed series. These books would be original novels set in invented worlds in which magic works. Each would have a male central character that would triumph over evil by his wits, innate virtue, prowess as a warrior, and with the help of a tutor or tutelary spirits. Fantasy novels and multi-volume series with deeper themes and much more complex characters, dealing with human drama on a personal level began to appear, novels that stood at the opposite end of the spectrum from the vast majority of Sword and Sorcery novels of the times, as I knew and remember it.

Among my personal favorites of this era are Stephen R. Donaldson’s Tolkien-inspired, but highly original Lord Foul’s Bane, The Illearth War, and The Power That Preserves, followed by his The Wounded Land, The One Tree, and White Gold Wielder. These featured Thomas Covenant, a modern-day leper suddenly drawn into another world: he is anything but a hero — he’s an anti-hero, and this series was far and away from what we’d call today “Young Adult Fantasy.” But it’s what I consider Donaldson’s masterpiece, his 2-volume Mordant’s Need — The Mirror of Her Dreams and A Man Rides Through — that were the game-changers for me. Donaldson brilliantly combined the conventions of the romance and Gothic novels with those of Heroic Fantasy. He presented to us an emotionally scarred, timid, and insecure woman whose growth into a mature, strong and defiant young heroine is at the heart of this fantastic “duology.” Add to the mix a rather hapless character that also grows during the story to become a true hero, some devilishly-wicked villains, the politics of empire, and a brilliant use of mirrors as tools of magic, and we have something different now, something I consider ground-breaking for its time. Up until then, there were few women who were lead characters in fantasy: the works of CL Moore, Leigh Brackett, Marion Zimmer-Bradley, Andre Norton, Janet Morris, CJ Cherryh, Barbara Hambly, Katherine Kurtz, Diana L. Paxson, and Diane Duane are some of the names that immediately spring to mind.

Heroic Fantasy Was Beginning to Grow, to Expand, Even Mature

By the late seventies and early eighties, the success of the del Rey formula was so confirmed that many other publishers began to publish in imitation. Dragons and unicorns began to appear all over the mass-market racks, and packaging codes with proper subliminal and overt signals developed. A whole new mass-market genre had been established. And IMHO, this was all for the good of the Heroic Fantasy genre: it needed to grow, to evolve, or it would stagnate and turn stale. In this way, “barbarian” Sword and Sorcery fiction, which has its roots in the masculine adventure of the early twentieth-century pulps, combined with the Gothic and horror elements that had become so popular in fiction magazines of the late 1920s into the Depression, was succeeded commercially — and very profitably — by novels that gave us more than just big, barbarian loners with swords, hacking and slashing their way to win or steal a treasure, to slay a wizard and rescue the helpless maiden. Heroic Fantasy was growing up, and for many, I suppose, this was not a good thing. People often want to keep their artists — filmmakers, musicians, authors — pigeon-holed and locked away in a box, writing, recording, and filming the same thing over and over again.

So, Why Wasn’t Sword & Sorcery Allowed to Grow Up?

One of the elements that often bothered me about Sword and Sorcery was its lack of complex and thoughtfully-developed characters, engaging dialogue that propelled the story and brought the characters to life, and the lack of real human drama and tragedy — the kind of plotting and drama we find in all good storytellers, from Shakespeare to Dickens, and other great novelists.

Dramatis gravitas, and often a sense of humor and irony — these are what so many of Barbarian Solo brand of Sword and Sorcery tales lacked. They were simple and straightforward, action-oriented adventure tales. And this was still a good thing. Most of these stories, in fact, were not meant to be anything more than that, of course, and that is in the grand tradition of some of the best pulp fiction. And yet… the possibilities were and are still there — and there’s plenty of room for both. Still, I asked myself why so many writers of the kind of Sword and Sorcery upon which I honed my blade were, to me, reluctant to let the genre grow up, to escape the box in which they were stuck? Was it money? To me, a number of writers did, later on, take the genre and give it room to grow. For example, Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time series and George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones certainly contain much of what sets Sword and Sorcery apart from a lot of the Heroic Fantasy that preceded them. Whatever you might think of those two series, there is that certain element of darkness and violence inherent in the best of Sword and Sorcery.

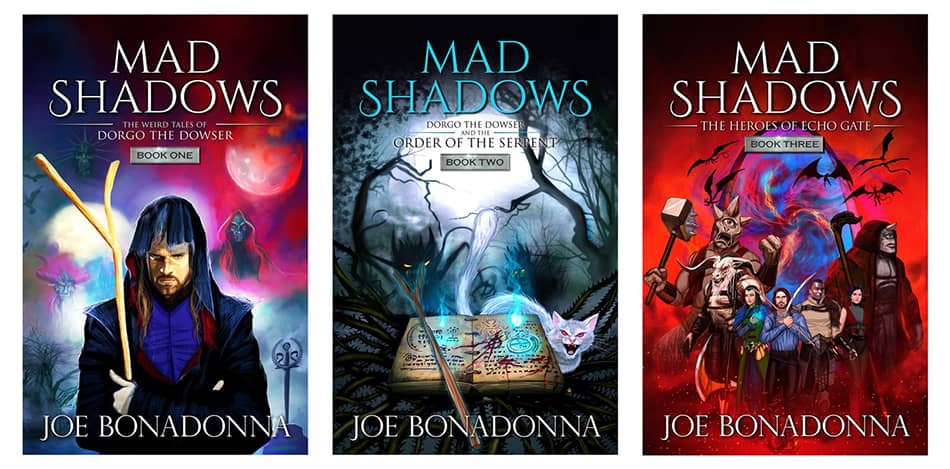

I must confess to being bored with endless volumes of a series that seems to wander all over the place, book after book after book, with no apparent end in sight. (I’d rather read ten stand-alone adventures, like for instance the James Bond novels, than struggle through ten books that are basically of one plot. But that’s just me.) People like their “door-stop” books, too. I received a fairly good Amazon review for my Mad Shadows — Book One: The Weird Tales of Dorgo the Dowser. The reviewer liked the book, like Dorgo’s six adventures, but gave the review only a three-star rating — because it was too short. Over 300 pages and 125-K words, it was not long enough for that person. Well, to each his or her own.

Thankfully, a New Sword and Sorcery and Heroic Fantasy Boom Has Been Underway For Quite Some Years Now

With a growing female audience, dedicated publishers, and an influx of daring young writers — including many gifted women who are bringing something new and fresh, bringing a new perspective, to the genre: Grace Draven, Robin McKinley, Sarah J. Maas, Sue Lynn Tan, Natasha Ngan, Alex Butcher, and Ellie Raine, for example. The genres are growing all the time, maturing . . . growing and flourishing. We should not shy away from change. There is nothing to fear. There is plenty of room for everything. I also hear a lot of poo-pooing, as I call it: dumping on some writer’s work, male or female, for one reason or another — and so many of those who do this “dissing” have not read the author’s work! It’s the same as trashing a film or TV show that you have never seen. I guess the old adage, “Never judge a book by its cover,” no longer applies. Maybe it’s all based on some kind of prejudice, especially from a certain segment of the male readership who want to keep their warriors free from being feminized, who even resent women from invading their little world of what they like by writing Sword & Sorcery, Heroic Fantasy, Science Fiction, and Horror. I truly have no idea what or why that is, and I certainly don’t understand that sort of mindset.

I also dislike it when people say that this or that of anything is the best. That’s just an opinion really, whether informed or not. I usually say, when pressed for an answer, that it’s one of my favorites. I don’t like what most people I know like. And most people I know… don’t like what I like. There really is no bad or good of anything if a book, a painting, a film or a piece of music has touched someone’s heart, touched their life. If it touched even one person, then that artist has succeeded and accomplished something. We may think there is, but really . . . there is no way to measure one person’s opinion against another person’s opinion. To do so would be like using “a yardstick for lunatics — one point of view,” to quote The Strawberry Alarm Clock. And that’s all it is, one point of view. (Maybe we should use something concrete, something tangible, to measure the worth of something: the more money it earns, the greater it is. But that’s just silly and totally wrong-headed, isn’t it?) I just ignore such people and refuse to argue with them. I mean, you may like possum pie, while I like grilled octopus. No big deal.) It’s all a matter of personal taste. That should be obvious to everyone. Anyway, I can’t figure it all out. I just chalk it up to what I said earlier: it’s your opinion against everyone else’s.

And You Know What They Say About Opinions

Joe Bonadonna

Joe Bonadonna is the author of the Gothic Noir fantasies Mad Shadows—Book One: The Weird Tales of Dorgo the Dowser (winner of the 2017 Golden Book Readers’ Choice Award for Fantasy); Mad Shadows—Book Two: The Order of the Serpent; Mad Shadows—Book Three: The Heroes of Echo Gate; the space opera Three Against The Stars and its sequel, the sword and planet space adventure, The MechMen of Canis-9; and the sword & sorcery pirate novel, Waters of Darkness, in collaboration with David C. Smith. With co-writer Erika M Szabo, he penned Three Ghosts in a Black Pumpkin (winner of the 2017 Golden Books Judge’s Choice Award for Children’s Fantasy), and its sequel, The Power of the Sapphire Wand.

He also has stories appearing in: Azieran: Artifacts and Relics; Savage Realms Monthly (March 2022); Griots 2: Sisters of the Spear; Heroika I: Dragon Eaters; Poets in Hell; Doctors in Hell; Pirates in Hell; Lovers in Hell; Mystics in Hell; Liars in Hell; Sinbad: The New Voyages, Volume 4; Unbreakable Ink; Stand Together — A Collection of Poems and Short Stories for Ukraine; the shared-world anthology Sha’Daa: Toys, in collaboration with author Shebat Legion; and with David C. Smith for the shared-universe anthology, The Lost Empire of Sol.

In addition to his fiction, Joe has written numerous articles, book reviews and author interviews for Black Gate online magazine.

Visit Joe’s Amazon Author’s page!

Think commercial factors were a big influence as well? The short story was the dominant form of the pulp era, and the stories in question tended to be colourful and action-orientated. The fact that they were often highly repetitious didn’t really matter: there was a month between one story and the next. Then the pulps were replaced by paperbacks. I guess Harlan Ellison – based on a recent article on Black Gate – was one casualty of the transition to a longer format. Fantasy in particular got much longer, thanks to LOTR.

And Conan was a serial character. The whole charm of a serial character is their consistency. Each week brings a different predicament, but we can always rely on Conan to reach for his trusty broadsword just like we can rely on Holmes to reach for his pipe. For a character to hold a reader’s interest over a longer format, they need to have some kind of arc – but a Conan who spends most of a book nursing a knee injury and having second thoughts about his life choices isn’t really Conan, anymore than a novel about Sherlock Holmes battling drug-addiction is really Sherlock Holmes.

I mostly agree with you. But times change and short stories can be a bit more “thoughtful,” unless one is rightly a certain type of pulp story. I think you’re spot on about Ellison. He was a short-story writer, but novel-length. I don’t think so. I heard once he was writing a sequel to A Boy and His Dog – a novel called Blood’s A Rover. I was looking forward to that, but as far as I know, and I gave up “the search” many a year ago, he never finished the novel.

Thank you, Seth Lindberg for setting this one up. Great Job! Thank you, John O’Neil, for publishing this!

Always a pleasure, Joe! 🙂

” (I’d rather read ten stand-alone adventures, like for instance the James Bond novels, than struggle through ten books that are basically of one plot. But that’s just me.)”

No, it’s not just you. 🙂

As I get older and have less time left, I tend to prefer stand-alones and shorter works. I’ve always read heavily in short fiction, but as I have less time left on this orb, my reading of short fiction has increased.

Thanks, Keith! I’ve been hearing from a lot of our generation who feel the same way. I’m at the point of concentrating on writing short fiction. I’d like to do another novel or two, but the short story format is more challenging, and I just don’t have the energy and time to devote to writing a novel. Oh, I long for those days of reading Ace Doubles and 70-K to 80-K novels.

I’m with you on writing the short fiction. That’s what I tend to focus on, short stories and novelettes, although I am working on a dark fantasy novel that should be the first volume of a trilogy.

Good luck with the writing.

Nice! Trilogies I have always liked – or quartets. But guys like George RR Martin and Robert Jordan . . . I got tired and bored of waiting for the next volume.

[…] (6) TOO MUCH THE SAME THING? At Black Gate, Joe Bonadonna talks about his personal experiences with the sword and sorcery genre and why it withered in the 1980s in “IMHO: A Personal History Of Sword & Sorcery And Heroic Fantasy”. […]

i’ll be honest, i am not sure other then almost every comic book, i have ever read any conan by someone other than Howard. i am sure i might have in some anthology or something, but nothing i remember.

it’s to bad a lot of them are out of print, i am sure at least a couple of them are decent enough.

i was made aware by Mr. Byrne there is a new one coming from the Dies the Fire author and if it’s not overly expensive i might try that.

There were a few good Conan pastiches: andy offutt, Karl Edward Wagner, Poul Anderson. But I didn’t read many of them. Oh, the de Camp-Carter stuff, sure, because they were part of the Lancer editions when I discovered Conan in the late 1960s. I’m not sure, but I think RA Salvatore is doing the new Conan novel.

There’s one from S. M. Stirling coming out later this fall, November, I think.

Thanks, Keith! I got the names wrong. Stirling, Salvatore . . . I knew it began with an S.

Thanks for this personal history. All our stories and histories are personal, and I think something is lost when we pretend otherwise–as if there’s some objective standard of subjective experience. I’m right there with you and the Strawberry Alarm Clock.

Re Björn Nyberg: I’m pretty sure his involvement in Conan pastiche dates back to the 50s, well before Lin Carter was involved. In fact, BN wrote a little about this is the fan magazine ERBania back in 1959. I idly googled it and was surprised to find a scan of the issue online.

https://fanac.org/fanzines/Erbania/Erbania06.pdf

So maybe Carter is kind of like the guy who climbed the ladder and then drew it up after him. Conans for him and his seniors in the pastiche biz, Clonans for everyone else. Or, more charitably, maybe he figured pastichers (?) should earn their spurs by doing other heroic fantasy before ascending to Conanity.

I haven’t read a lot of Conan pastiche, apart from the ones in the old Lancer/Ace series by de Camp etc (which were meh-to-okay), and John C. Hocking’s Emerald Lotus (which I liked).

But, in general, I think Hemingway was right: “What a writer in our time has to do is write what hasn’t been written before or beat dead men at what they have done.”

Thanks very much, James! Thanks for that link, too. I never knew Nyberg was associated with Conan back in the 50s. You make 2 excellent points about Carter, who had also created a Clonan named Thongor.

It was exciting, when I was a high school student, to get a couple of letters from Lin Carter (whose stationery included a quick sketch of Conan by Frazetta). I’d written about his anthology New Worlds for Old. Later, I wrote to de Camp to praise his Lovecraft biography, and he was even more ready a correspondent than Carter. I appreciated that, and still do, though now their fantasy doesn’t interest me very much.

I apologize for the long-overdue response, Dale. I remember his stationery and the Frazetta sketch. Someone told me Carter had other stationery featuring a sketch of his Thongor. People can say whatever they want about Carter, but if not for him, where would S&S and HF be today? And if not for him, I probably would never have known of the novels and writers who published long before even I was born!

Thanks, Dale. I feel the same as you.

Great piece, Joe! The best thing that happened to S&S might have been Moorcock taking it away from its solo-barbarian roots. Rereading Stormbringer reminded me how different he is from Howard and how equally grand is his storytelling. I don’t keep up on the ‘zines anymore, but the wealth and quality of solid S&S sorts out there over the past decade has been tremendous.

I find the genre works best in concentrated doses, but clearly what’s selling are the big books and long series. I’m curious how/why the split, which seems almost generational, over short stories/short novels and endless series came about. It’s an easy line, but it’s a rare book I find that needs to be as long as Bleak House.

Thank you very much, Fletcher. Sorry for the long delay in my replying, but I had totally forgot that I wrote this, due to real life getting in the way and TAKING me away from it all.

Anyone’s curious about the generational shift In fantasy from suddenly everything all of a sudden being trilogy’s… Here is an interesting take

The Artificial Fantasy Trilogy Since 1977 ( why most recent Sword & Sorcery is bloated and artless)

https://youtu.be/zk9TnCizZdM?si=s5qEb_NmNfDn5ai1

Good essay. Enjoyed reading it. I agree with you on the Donaldson books, some of the best of that bigger fantasy explosion. I tend to think Fafhrd was a bit muscle bound though. Leiber is often described as being more realistic than Howard but I think it’s exactly the opposite. His Fafhrd and Gray Mouser stories are certainly entertaining but I get less of a sense of realism when I read them than I do from REH’s work, especially his Bran Mak Morn stories.

Thanks, Charles. I’m somewhat split on agreeing and disagreeing with you on Lieber, lol! I did always view Fafhrd and Mouser as more pure fantasy than REH, and always thought that Fafhrd was sort of a comical version of Conan. For me it was the tongue-in-cheek, nudge-nudge-wink-wink sense of humor, the character interaction, and the crazy plots that sold me on Leiber. His early stories are wonderful, but the last 2 books in the series I always found to be rather weak, on the whole, than the others.