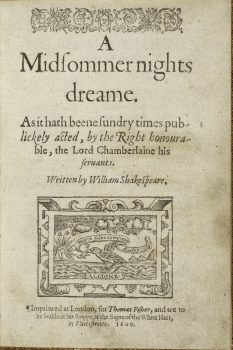

The Sillliest Stuff I’ve Ever Read: A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare

’Tis strange, my Theseus, that these lovers speak of.

THESEUS

More strange than true. I never may believe

These antique fables, nor these fairy toys.

Lovers and madmen have such seething brains,

Such shaping fantasies, that apprehend

More than cool reason ever comprehends.

The lunatic, the lover, and the poet

Are of imagination all compact:

One sees more devils than vast hell can hold;

That is the madman: the lover, all as frantic,

Sees Helen’s beauty in a brow of Egypt:

The poet’s eye, in a fine frenzy rolling,

Doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven;

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen

Turns them to shapes, and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.

Such tricks hath strong imagination,

That if it would but apprehend some joy,

It comprehends some bringer of that joy.

Or in the night, imagining some fear,

How easy is a bush supposed a bear?

If you take the time to skim over the history of criticism of William Shakespeare’s sublime A Midsummer Night’s Dream (ca. 1596), you might lose your mind. Early commentary seems to have centered on the appropriateness of depicting imaginary beings such as the fairies while more contemporary scholars (say, over the last fifty years) have seen support, as well as opposition, to such things as patriarchy and the “hegemonic order.” All sorts of dark sexual allusions are intimated by several authors.

It’s not all like that, with much focus on metatextual aspects like artistic creation, dream versus illusion, or metamorphosis. Some of this is interesting, some of it ridiculous.

Oh, there are things being said about art, love, and perception, but little of that matters much to me, and none of it matters to the pleasures of the play. For my tastes, the most accurate comment about A Midsummer Night’s Dream is from Thomas McFarland, who described it as “dominated by a mood of happiness and that it is one of the happiest literary creations ever produced.”

For those unfamiliar with A Midsummer Night’s Dream, it follows four plots: the impending marriage of Duke Theseus and Queen Hippolyta; the romantic entanglements of two pairs of young Athenians; the efforts of a group of “rude mechanicals” (laborers) to stage a nuptial play for their king; and, finally, the marital discord between Oberon and Titania, the king and queen of the fairies. At various points in the play, the four stories weave together, creating a chaotic affair replete with fairy magic and buffoonery that all coalesce into one wonderfully perfect ending.

The play begins with Theseus, duke of Athens, complaining to his betrothed, Hippolyta, queen of the Amazons, that the four days until their wedding is frustrating his desires. She tells him “(f)our nights will quickly dream away the time will pass swiftly.” One of his subjects, Egeus, then brings a complaint before him. Egeus desires his daughter, Hermia, to marry Demetrius. Hermia, though, is in love with Lysander. According to Athenian custom, if she goes against her father’s wish, she faces death or must become a chaste nun of the goddess Diana. Rejecting both options, Hermia and Lysander decide to steal away into the forest outside Athens. Along the way, Hermia, foolishly it will turn out, tells her friend, Helena, what she’s doing. Helena, who is desperately in love with Demetrius despite his brutal rejection, tells him in hopes it will somehow drive him towards her. As Lysander says earlier, “The course of true love never did run smooth.”

With this setup, one might think Shakespeare might be aiming towards some of the same separated-by-family-rivalry territory trod by Romeo and Juliet, but the introduction of the players quickly disabuses the reader of that idea. Unlike the rest of the play’s characters, the actors don’t have classical names, but, instead, good 16th century British ones. While Theseus, one of the great characters of Classical Greek mythology, rules Athens, among his subjects are Peter Quince, Francis Flute, Tom Snout, and Nick Bottom. Their intention is to stage a production of The most lamentable comedy and most cruel death of Pyramus and Thisbe, a story that does echo Romeo and Juliet.

As soon as writer and director Quince begins assigning parts, the silliness begins. Bottom, convinced of his own brilliance, despite already being given the biggest role of Pyramus, declares:

And I may hide my face, let me play Thisbe too. I’ll speak in a monstrous little voice; ‘Thisne, Thisne!’—‘Ah, Pyramus, my lover dear! thy Thisbe dear! and lady dear!’

and moments later:

Let me play the lion too. I will roar that I will do any man’s heart good to hear me. I will roar that I will make the Duke say ‘Let him roar again, let him roar again.’

As the company makes it plans to rehearse the following day, it is clear whatever happens next, their production will be a disaster.

Finally, in the following scene, the fairies appear. Oberon is incensed that Titania, who has come to Athens to attend Theseus’ and Hippolyta’s wedding, won’t turn over a changeling, a child she has stolen from an Indian king. He wants the child as a “(k)night of his train, to trace the forests wild.” Son of one her priestesses who recently died, Titania will not let the boy go. In retaliation for his queen’s disobedience, Oberon sends his servant, Puck, to secure a certain flower. Later, while she sleeps, he shall douse her eyes with its juice whereupon:

The next thing then she waking looks upon

(Be it on lion, bear, or wolf, or bull,

On meddling monkey, or on busy ape)

She shall pursue it with the soul of love.

While Puck searches out the flower, Oberon spies upon Helena following Demetrius through the woods as he searches for Hermia and Lysander. She begs for his love and promises to love him more than Hermia ever will, but he only dismisses her with cruel insults.

I’ll run from thee and hide me in the brakes,

And leave thee to the mercy of wild beasts.

Outraged by Demetrius’s actions, Oberon instructs Puck to treat not only Titania’s, but also “(a)noint his eyes; But do it when the next thing he espies May be the lady,“.

Puck puckishly sets about his tasks. Unfortunately, he doses Lysander instead, and he falls madly in love with Helena. Later, attempting to rectify the situation, Oberon manages to enchant Demetrius but without correcting Puck’s mistake. Soon, both young men are ardently pursuing Helena who now believes she’s being made sport of. When Hermia finds the trio, things only get madder. Cruelties are uttered and violence is threatened.

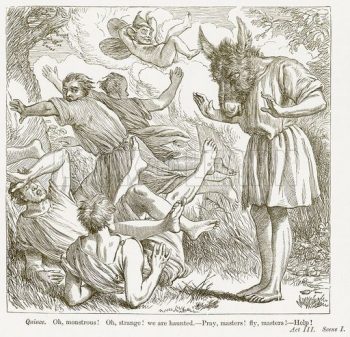

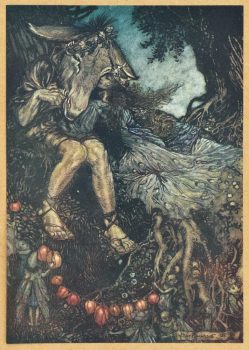

With Titania, Puck is much more successful. When he comes across the players rehearsing near the sleeping fairy queen, he changes Bottom’s head into that of an ass and drips the potion into her eyes. Bottom’s transformation terrifies his friends and drives them away. Left alone, he sings to himself, which wakens the fairy. Upon seeing him she immediately falls in love. The contrast between her high-flown words of love and his down-to-earth responses is perfection.

With Titania, Puck is much more successful. When he comes across the players rehearsing near the sleeping fairy queen, he changes Bottom’s head into that of an ass and drips the potion into her eyes. Bottom’s transformation terrifies his friends and drives them away. Left alone, he sings to himself, which wakens the fairy. Upon seeing him she immediately falls in love. The contrast between her high-flown words of love and his down-to-earth responses is perfection.

TITANIA.

What, wilt thou hear some music, my sweet love?BOTTOM.

I have a reasonable good ear in music. Let us have the tongs and the bones.TITANIA.

Or say, sweet love, what thou desirest to eat.BOTTOM.

Truly, a peck of provender; I could munch your good dry oats. Methinks I have a great desire to a bottle of hay: good hay, sweet hay, hath no fellow.TITANIA.

I have a venturous fairy that shall seek

The squirrel’s hoard, and fetch thee new nuts.BOTTOM.

I had rather have a handful or two of dried peas. But, I pray you, let none of your people stir me; I have an exposition of sleep come upon me.TITANIA.

Sleep thou, and I will wind thee in my arms.

Fairies, be gone, and be all ways away.

So doth the woodbine the sweet honeysuckle

Gently entwist, the female ivy so

Enrings the barky fingers of the elm.

O, how I love thee! How I dote on thee!

There seem to have been few props or sets for plays in his period, and it’s all down to Shakespeare’s words to create the magic-filled forest outside Athens. The four lovers are constantly under the eyes of the fairies who, nonetheless, remain hidden from their view. When Titania becomes smitten with Bottom, she commands her retinue to bring him, not mere gold and silver, but all the fairest treasures of the wood;

Be kind and courteous to this gentleman;

Hop in his walks and gambol in his eyes;

Feed him with apricocks and dewberries,

With purple grapes, green figs, and mulberries;

The honey-bags steal from the humble-bees,

And for night-tapers, crop their waxen thighs,

And light them at the fiery glow-worm’s eyes,

To have my love to bed and to arise;

And pluck the wings from painted butterflies,

To fan the moonbeams from his sleeping eyes.

Nod to him, elves, and do him courtesies.

The forest is a place of enchantment, where there can be no simple explanation for the strange things that transpire inside its boundaries. The young Athenians, unable to clearly remember the night before, wonder if all was only a dream.

In the end, things are set right by Oberon. Lysander’s and Hermia’s love is restored and Demetrius and Helena are in love. When Theseus sees how the couples are now aligned, he calls for a group wedding, dismissing Egeus’s charges against his daughter. Once that’s done, all that remains is the staging of Pyramus and Thisbe. The final act of A Midsummer Night’s Dream is one of the most ridiculous things Shakespeare ever penned. Between the terrible, and terribly delivered, lines of the play, the audience pokes fun at the actors. Only Theseus makes an effort to give any concessions to the mechanicals’ artistry, uttering one of the kindest lines of any critic ever: “If we imagine no worse of them than they of themselves, they may pass for excellent men.”

The play concludes with Puck speaking to the audience directly, telling them all they’ve seen may, indeed, be only a dream. Which, of course, as it’s the product of Shakespeare’s literary fecundity, that’s all it really is.

If we shadows have offended,

Think but this, and all is mended,

That you have but slumber’d here

While these visions did appear.

And this weak and idle theme,

No more yielding but a dream,

Gentles, do not reprehend.

If you pardon, we will mend.

And, as I am an honest Puck,

If we have unearnèd luck

Now to ’scape the serpent’s tongue,

We will make amends ere long;

Else the Puck a liar call.

So, good night unto you all.

Give me your hands, if we be friends,

And Robin shall restore amends.

My reviews don’t usually give away so much of the plot, but it seemed valuable here to convey the frothy fun and simplicity of the play. There is no great plumbing of a man’s soul or pondering on the meaning of existence in this play. The greatness of A Midsummer Night’s Dream lies in the headiness and beauty of its lines, such as these when the four young lovers have awoken:

DEMETRIUS.

These things seem small and undistinguishable,

Like far-off mountains turnèd into clouds.HERMIA.

Methinks I see these things with parted eye,

When everything seems double.HELENA.

So methinks.

And I have found Demetrius like a jewel,

Mine own, and not mine own.DEMETRIUS.

Are you sure

That we are awake? It seems to me

That yet we sleep, we dream. Do not you think

The Duke was here, and bid us follow him?

Or these, when Puck urges Oberon to quick action as morning approaches:

PUCK.

My fairy lord, this must be done with haste,

For night’s swift dragons cut the clouds full fast;

And yonder shines Aurora’s harbinger,

At whose approach, ghosts wandering here and there

Troop home to churchyards. Damnèd spirits all,

That in cross-ways and floods have burial,

Already to their wormy beds are gone;

For fear lest day should look their shames upon,

They wilfully themselves exile from light,

And must for aye consort with black-brow’d night.OBERON.

But we are spirits of another sort:

I with the morning’s love have oft made sport;

And, like a forester, the groves may tread

Even till the eastern gate, all fiery-red,

Opening on Neptune with fair blessèd beams,

Turns into yellow gold his salt-green streams.

But, notwithstanding, haste, make no delay.

We may effect this business yet ere day.

A Midsummer’s Night Dream is also funny as all get-out. Clearly, most of it comes from the silliness of the actors, but Shakespeare wasn’t one to rely solely on slapstick, as there’s as much laughter to be wrung from his words as the characters’ actions. From the moment Peter Quince enters the stage and recites the prologue to Pyramus and Thisbe, the interjections begin.

PROLOGUE

If we offend, it is with our good will.

That you should think, we come not to offend,

But with good will. To show our simple skill,

That is the true beginning of our end.

Consider then, we come but in despite.

We do not come, as minding to content you,

Our true intent is. All for your delight

We are not here. That you should here repent you,

The actors are at hand, and, by their show,

You shall know all that you are like to know.THESEUS.

This fellow doth not stand upon points.

LYSANDER.

He hath rid his prologue like a rough colt; he knows not the stop. A good moral, my lord: it is not enough to speak, but to speak true.

HIPPOLYTA.

Indeed he hath played on this prologue like a child on a recorder; a sound, but not in government.

THESEUS.

His speech was like a tangled chain; nothing impaired, but all disordered. Who is next?

Of course, it doesn’t hurt that in most productions, the actors are encouraged to be as awful and incompetent as they can be. Together, the result is one of Shakespeare’s most outright funny and silly plays. I’m not actually sure if I’ve ever read the play before this week, but I did see it performed while I was in high school. The American Shakespeare Theatre production at Stratford, Connecticut (starring Kelsey Grammer and Roy Dotrice) was terrific and the theater packed with high school students rocked with laughter. A Midsummer Night’s Dream is often considered one of the most accessible of Shakespeare’s plays, and that’s understandable.

I love this play. If I had to choose a single Shakespeare play — something I’d never do willingly — it would probably be Macbeth, a short, sharp, shock of a play. This, though, is the one I’d recommend to any newcomer to the Bard of Avon. Whether read or performed, all you need to do is relax and allow the gorgeousness and richness and absurdity of A Midsummer Night’s Dream to wash over you.

If you’ve missed out on seeing, or at least reading, A Midsummer’s Night Dream, rectify that failing at once. While there are several movies available, none does full justice to the play. The 1935 version suffers from an over-acting Mickey Rooney as Puck. The wonderfully cast 1968 version — Ian Richardson, Judi Dench, Dianna Rigg, Helen Mirren, David Warner, Ian Holm — looks like a hippy had a very cheap, very bad trip. The 1999 version with Rupert Everett, Michelle Pfeiffer, and Stanley Tucci is best left alone. Instead, find a staged production, no matter how amateurish.

Or watch Mr. Magoo’s version from 1965 ;D

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

Sorry you didn’t quote Bottom’s dream; I think it is, in its way, one of the most profound and moving things in Shakespeare:

I have had a most rare vision. I have had a dream—past the wit of man to say what dream it was. Man is but an ass if he go about to expound this dream. Methought I was—there is no man can tell what. Methought I was, and methought I had—but man is but a patched fool if he will offer to say what methought I had. The eye of man hath not heard, the ear of man hath not seen, man’s hand is not able to taste, his tongue to conceive, nor his heart to report what my dream was. I will get Peter Quince to write a ballad of this dream. It shall be called “Bottom’s Dream” because it hath no bottom. And I will sing it in the latter end of a play before the duke. Peradventure, to make it the more gracious, I shall sing it at her death.

I’ve seen a couple of very odd productions of this play (for some reason, it’s one of those that prompts directors to overflow the banks of legitimate innovation). In one, the characters were all rock and rollers – Oberon was portrayed as Elvis. The less said the better. In another production, the sets and costumes were all done as if by Doctor Seuss. It was a real treat for the eye, and the acting and direction leaned a bit in that direction but not so much as to make the play fall on its face. Overall, it was a successful idea and I still remember it fondly after thirty-five years.

And you’re right; it’s gorgeous. At some point, I had to quit. This is one of the pieces where I could’ve just reprinted the entire text.

I saw a production of this as a kid. I might not have understood it all but I found it amusing even then. I do remember being surprised that Shakespeare wrote comedies. I don’t know why but I assumed his plays were stuffy old things.

I was lucky to have terrific high school teachers who made me fall in love with his work. I’ve only read/seen about a third of his plays, so I’ve got plenty more to go.

It’ the only live production I’ve seen. I really need to see more. Shakespeare is great both for his use of language and the fact that he can tell a compelling story.

I’ve seen this play performed live twice: once as a college freshman, done by a troupe from a visiting college, and the second, more than twenty years later, at the Stratford Shakespeare Festival in Ontario. The latter featured Colm Feore (“Gotham.” “The Umbrella Academy”) and Sheila McCarthy, and the costuming looked like it was done by a punk approach to “Rocky Horror,” with appropriate accompanying music. Odd, but very professional, and fun. The college kids I saw in 1968 had the entire audience laughing out loud for the whole production. I hadn’t known Shakespeare could be so funny.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream was the first Shakespeare play that I ever read, way back before high school, even. I would like to proclaim my precocity, but the most likely motivator was previously reading the Classics Illustrated comics version and getting the notion that I should try the original, since the story was so wonderfully silly. And before you ask, yes, a great deal of my knowledge and love of classical music does, in fact, derive from Looney Tunes cartoons. Clearly, if comic books and television rotted my brain, they did so in a high-brow way at least.

I still have my Classics Illustrated version, purchased longer ago than I care to remember (50+ years…)

That’s how I first read War of the Worlds and Ivanhoe.

This play is one of the reasons I recommend that anyone who wants to write dialogue in English needs to listen to Shakespeare or better yet, declaim some of his words aloud to yourself. The words in this play seem to have a magic that awakens in the hands of amateurs (and which none of the films seem to be able to capture) and Mr. McFarland is right: it is a happy work of art.

Thank you, Mr. Vredenburgh

Thank you very much. Reading The Tempest last year, and now this, makes me think I might actually finally pick up my copy of A Winter’s Tale

I actually directed a production of this play, when I was a student in the 1970s. My first introduction to it was when I was 12 and it was hardly successful but, later, when I was 14 another English teacher took us through it. I can’t remember what part I read but I do remember that the part of Nick Bottom was played by a lad who was a dead ringer – boastful, full of himself and often got himself into awkward scrapes. After that, I have always loved this play and have seen a fair few performances. My favourite line remains “All for your delight we are not here”, from the mechanical’s prologue to their production. A complete contradiction, because, of course, without them being “here”, there would be no “delight”.

It’s a toss up between Dream and Twelfth Night as my favourite of Shakes’ comedies. I’ve been involved in three productions of Dream and had a chance to play Sir Toby in 12th Night which was a great deal of fun. I’d also recommend tracking down clips of Peter Brooks production of Dream which certainly emphasizes the dream aspect and shows a very different but engaging style to the play. Only wish I could have seen it in person. As for the 99 film version, its perfectly serviceable though nothing too remarkable. A safe choice to play while teaching your grade 9 English class.