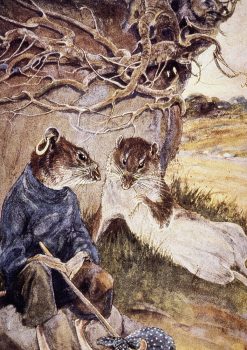

The Sound of Far-Away Music: The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame

“Hullo, Mole!” said the Water Rat.

“Hullo, Rat!” said the Mole.

So begins one of the greatest of literary friendships. That simple introduction between two soon-to-be-best friends has stuck with me ever since my dad first read me The Wind in the Willows (1908). They’re the opening chords of a song like the dream-music Mole and Rat hear on a mysterious river island, that has remained with me my entire life. Even, if like them, I can’t remember all the words, it’s a song that’s “simple–passionate–perfect.”

This book, one I find wonderful beyond measure, is a collection of several distinct tales. The most famous, probably due to Walt Disney’s The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949) and the attendant amusement park ride, involves the foolish escapades of Toad. Those chapters are riotously funny and, I’d imagine, the most easily enjoyable to any child hearing them. More of the book, however, involves Mole and Rat, and those parts are by turns wistful, melancholic, and wondrous. In his memoir, Christopher Robin Milne wrote:

A book that we all greatly loved and admired and read aloud or alone, over and over and over: The Wind in the Willows. This book is, in a way, two separate books put into one. There are, on the one hand, those chapters concerned with the adventures of Toad; and on the other hand there are those chapters that explore human emotions – the emotions of fear, nostalgia, awe, wanderlust. My mother was drawn to the second group, of which “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn” was her favourite, read to me again and again with always, towards the end, the catch in the voice and the long pause to find her handkerchief and blow her nose. My father, on his side, was so captivated by the first group that he turned these chapters into the children’s play, Toad of Toad Hall. In this play one emotion only is allowed to creep in: nostalgia.

If I thought I could get away with it, I’d just write out all of The Pipers at the Gates of Dawn for this piece and leave it at that. I believe it is one of the most affecting things I’ve ever read. Its beauty only grows with each read. Sadly, I must write more (but I’ll still quote it a lot).

Kenneth Grahame’s childhood was mired in tragedy. For much of his adult life, he was stuck in a dull job he disliked, especially when he barely escaped being killed by a disgruntled customer who fired three shots at him. His marriage was cold and loveless. His only child, Alistair, was born prematurely, blind in one eye, sickly his whole short life which he ended by suicide just before his twentieth birthday.

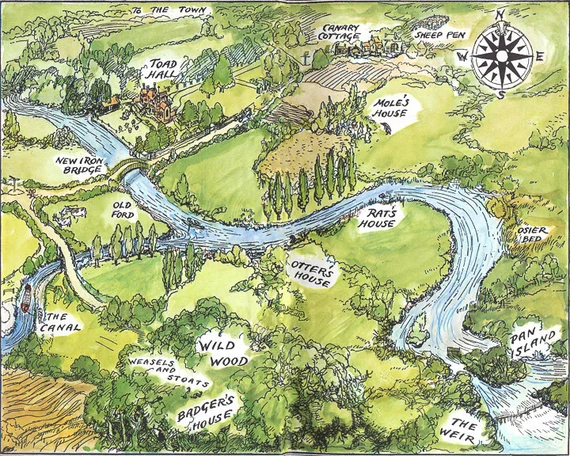

But when Alistair was a young boy of four, Grahame began telling him stories about Toad, a character whose willfulness and frequent obsession with one fad after another were inspired by Alistair, himself. When Grahame vacationed away from his family, he wrote stories in letters home to his son, introducing Mole, Rat (really a water vole), and Badger. At its heart, Wind in the Willows is about longing; for the beauty and comforts of the Edwardian countryside and for the bonds of friendship.

One day, while doing his spring cleaning, Mole is hit by a “spirit of divine discontent and longing” and sets off in search of something better than dust and whitewash. When he encounters a river for the first time:

When he encounters a river for the first time:

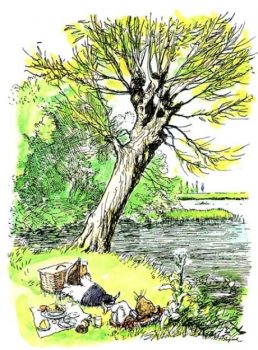

He thought his happiness was complete when, as he meandered aimlessly along, suddenly he stood by the edge of a full-fed river. Never in his life had he seen a river before — this sleek, sinuous, full-bodied animal, chasing and chuckling, gripping things with a gurgle and leaving them with a laugh, to fling itself on fresh playmates that shook themselves free, and were caught and held again. All was a-shake and a-shiver — glints and gleams and sparkles, rustle and swirl, chatter and bubble. The Mole was bewitched, entranced, fascinated. By the side of the river he trotted as one trots, when very small, by the side of a man who holds one spellbound by exciting stories; and when tired at last, he sat on the bank, while the river still chattered on to him, a babbling procession of the best stories in the world, sent from the heart of the earth to be told at last to the insatiable sea.

It’s along the banks of the river that Mole and Rat meet. They quickly strike up a friendship over a picnic lunch, which includes

“coldtonguecoldhamcoldbeefpickledgherkinssaladfrenchrolls–cresssandwichespottedmeatgingerbeerlemonadesodawater”

and Rat introduces Mole to “messing about in boats.” Soon they will undertake, together and apart, a series of adventures and encounters, including one with the supernatural.

The first adventure involves taking to the road in a “gipsy caravan” with Toad, who has only recently abandoned a love of boating.

“O, pooh! boating!” interrupted the Toad, in great disgust. “Silly boyish amusement. I’ve given that up long ago. Sheer waste of time, that’s what it is. It makes me downright sorry to see you fellows, who ought to know better, spending all your energies in that aimless manner. No, I’ve discovered the real thing, the only genuine occupation for a lifetime. I propose to devote the remainder of mine to it, and can only regret the wasted years that lie behind me, squandered in trivialities. Come with me, dear Ratty, and your amiable friend also, if he will be so very good, just as far as the stable-yard, and you shall see what you shall see!”

He led the way to the stable-yard accordingly, the Rat following with a most mistrustful expression; and there, drawn out of the coach-house into the open, they saw a gipsy caravan, shining with newness, painted a canary-yellow picked out with green, and red wheels.

“There you are!” cried the Toad, straddling and expanding himself. “There’s real life for you, embodied in that little cart. The open road, the dusty highway, the heath, the common, the hedgerows, the rolling downs! Camps, villages, towns, cities! Here to-day, up and off to somewhere else to-morrow! Travel, change, interest, excitement! The whole world before you, and a horizon that’s always changing! And mind! this is the very finest cart of its sort that was ever built, without any exception. Come inside and look at the arrangements. Planned ’em all myself, I did!”

The Mole was tremendously interested and excited, and followed him eagerly up the steps and into the interior of the caravan. The Rat only snorted and thrust his hands deep into his pockets, remaining where he was.

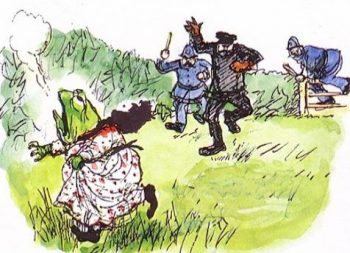

The trio embarks on a road trip that ends in disaster, the caravan overturned in a ditch with shattered wheels. Worse, Toad is introduced to automobiles, much to his great detriment. Among his escapades, there’s a jailbreak, a railroad chase, horse stealing, and, of course, several car crashes. When he steals and crashes a car he ends up brought up before the court.

The trio embarks on a road trip that ends in disaster, the caravan overturned in a ditch with shattered wheels. Worse, Toad is introduced to automobiles, much to his great detriment. Among his escapades, there’s a jailbreak, a railroad chase, horse stealing, and, of course, several car crashes. When he steals and crashes a car he ends up brought up before the court.

“To my mind,” observed the Chairman of the Bench of Magistrates cheerfully, “the only difficulty that presents itself in this otherwise very clear case is, how we can possibly make it sufficiently hot for the incorrigible rogue and hardened ruffian whom we see cowering in the dock before us. Let me see: he has been found guilty, on the clearest evidence, first, of stealing a valuable motor-car; secondly, of driving to the public danger; and, thirdly, of gross impertinence to the rural police. Mr. Clerk, will you tell us, please, what is the very stiffest penalty we can impose for each of these offences? Without, of course, giving the prisoner the benefit of any doubt, because there isn’t any.”

The Clerk scratched his nose with his pen. “Some people would consider,” he observed, “that stealing the motor-car was the worst offence; and so it is. But cheeking the police undoubtedly carries the severest penalty; and so it ought. Supposing you were to say twelve months for the theft, which is mild; and three years for the furious driving, which is lenient; and fifteen years for the cheek, which was pretty bad sort of cheek, judging by what we’ve heard from the witness-box, even if you only believe one-tenth part of what you heard, and I never believe more myself—those figures, if added together correctly, tot up to nineteen years—”

“First-rate!” said the Chairman.

“—So you had better make it a round twenty years and be on the safe side,” concluded the Clerk.

“An excellent suggestion!” said the Chairman approvingly. “Prisoner! Pull yourself together and try and stand up straight. It’s going to be twenty years for you this time. And mind, if you appear before us again, upon any charge whatever, we shall have to deal with you very seriously!”

Toad is easily the most memorable character in The Wind in the Willows. Mole, Rat, and Badger are all calmer, more introspective creatures while Toad is all wild excitement and enthusiasm. If there’s a primary theme in the book, it’s the need for Toad’s wild, antic ways to be reined in, something his kind-hearted and stolid friends willingly do. When he loses everything when the stoats and weasels of the Wild Wood seize Toad Hall, they even put their own lives at risk to stand by Toad. The story of Toad is a conservative one, pointing out the pitfalls of arrogance, inconstancy, and immaturity.

Except for the Disney movie, I don’t particularly love any of the other filmed versions of the book, but the antic Rik Mayall as Toad (also Alan Bennett as Mole, Michael Palin as Rat, and Sir Michael Gambon as Badger) in the 1995 animated version is perfection.

For me, though, like Christopher Robin’s mother, I’m drawn most deeply to the other parts of The Wind in the Willows. The most memorable are the previously referenced The Piper at the Gates of Dawn and Wayfarers All. Both chapters have been eliminated from some reprints of the book, and only included in a few of the filmed versions.

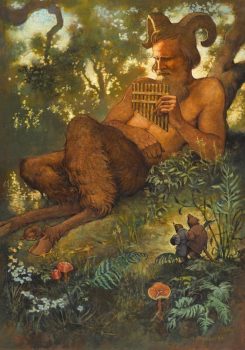

All his life, Grahame seems to have been drawn to a simple pantheism he embodied in a love of the countryside and all its simpler pleasures. When Mole and Rat set off down the river, hunting for Otter’s missing son, Portly, they find themselves, instead, on the hunt for some haunting melody, some dream of a time and place they’d never visited before, but know of deep within their souls.

All his life, Grahame seems to have been drawn to a simple pantheism he embodied in a love of the countryside and all its simpler pleasures. When Mole and Rat set off down the river, hunting for Otter’s missing son, Portly, they find themselves, instead, on the hunt for some haunting melody, some dream of a time and place they’d never visited before, but know of deep within their souls.

Slowly, but with no doubt or hesitation whatever, and in something of a solemn expectancy, the two animals passed through the broken, tumultuous water and moored their boat at the flowery margin of the island. In silence they landed, and pushed through the blossom and scented herbage and undergrowth that led up to the level ground, till they stood on a little lawn of a marvellous green, set round with Nature’s own orchard-trees—crab-apple, wild cherry, and sloe.

“This is the place of my song-dream, the place the music played to me,” whispered the Rat, as if in a trance. “Here, in this holy place, here if anywhere, surely we shall find Him!”

Then suddenly the Mole felt a great Awe fall upon him, an awe that turned his muscles to water, bowed his head, and rooted his feet to the ground. It was no panic terror—indeed he felt wonderfully at peace and happy—but it was an awe that smote and held him and, without seeing, he knew it could only mean that some august Presence was very, very near. With difficulty he turned to look for his friend, and saw him at his side, cowed, stricken, and trembling violently. And still there was utter silence in the populous bird-haunted branches around them; and still the light grew and grew.

Perhaps he would never have dared to raise his eyes, but that, though the piping was now hushed, the call and the summons seemed still dominant and imperious. He might not refuse, were Death himself waiting to strike him instantly, once he had looked with mortal eye on things rightly kept hidden. Trembling he obeyed, and raised his humble head; and then, in that utter clearness of the imminent dawn, while Nature, flushed with fulness of incredible colour, seemed to hold her breath for the event, he looked in the very eyes of the Friend and Helper; saw the backward sweep of the curved horns, gleaming in the growing daylight; saw the stern, hooked nose between the kindly eyes that were looking down on them humorously, while the bearded mouth broke into a half-smile at the corners; saw the rippling muscles on the arm that lay across the broad chest, the long supple hand still holding the pan-pipes only just fallen away from the parted lips; saw the splendid curves of the shaggy limbs disposed in majestic ease on the sward; saw, last of all, nestling between his very hooves, sleeping soundly in entire peace and contentment, the little, round, podgy, childish form of the baby otter. All this he saw, for one moment breathless and intense, vivid on the morning sky; and still, as he looked, he lived; and still, as he lived, he wondered.

“Rat!” he found breath to whisper, shaking. “Are you afraid?”

“Afraid?” murmured the Rat, his eyes shining with unutterable love. “Afraid! Of Him? O, never, never! And yet—and yet—O, Mole, I am afraid!”

The chapter Wayfarers All begins with Rat upset at all the animals readying for their fall migrations. Why would anyone turn their back on the beauty of the riverbank and head for parts unknown? Even when a trio of swallows explains their desires to him — “In due time,” said the third, “we shall be home-sick once more for quiet water-lilies swaying on the surface of an English stream. But to-day all that seems pale and thin and very far away. Just now our blood dances to other music” — he’s still angry.

It’s only when he meets a seafaring rat bound for the ocean after a season ashore, that Rat is infected with an overwhelming wanderlust.

The Sea Rat, as soon as his hunger was somewhat assuaged, continued the history of his latest voyage, conducting his simple hearer from port to port of Spain, landing him at Lisbon, Oporto, and Bordeaux, introducing him to the pleasant harbours of Cornwall and Devon, and so up the Channel to that final quayside, where, landing after winds long contrary, storm-driven and weather-beaten, he had caught the first magical hints and heraldings of another Spring, and, fired by these, had sped on a long tramp inland, hungry for the experiment of life on some quiet farmstead, very far from the weary beating of any sea.

Spellbound and quivering with excitement, the Water Rat followed the Adventurer league by league, over stormy bays, through crowded roadsteads, across harbour bars on a racing tide, up winding rivers that hid their busy little towns round a sudden turn; and left him with a regretful sigh planted at his dull inland farm, about which he desired to hear nothing.

By this time their meal was over, and the Seafarer, refreshed and strengthened, his voice more vibrant, his eye lit with a brightness that seemed caught from some far-away sea-beacon, filled his glass with the red and glowing vintage of the South, and, leaning towards the Water Rat, compelled his gaze and held him, body and soul, while he talked. Those eyes were of the changing foam-streaked grey-green of leaping Northern seas; in the glass shone a hot ruby that seemed the very heart of the South, beating for him who had courage to respond to its pulsation. The twin lights, the shifting grey and the steadfast red, mastered the Water Rat and held him bound, fascinated, powerless.

In the end, only Mole’s intervention keeps him from following the Wayfarer to the sea. As with so much of the book, this part is suffused with a deep wistfulness. Even if Rat understands he really can’t take to the waves, not doing so leaves an ocean-shaped hole in his heart. I think it might even be the real heart of the book. Dreams so often must remain dreams and have to fade in the face of obligation and responsibilities. It’s a hard lesson to find in a children’s story, but I suspect for a man who was bound by similar fetters it veers toward autobiography.

Decades before The Wind in the Willows, Grahame had found a measure of success writing two collections of reminiscences of childhood – The Golden Age and Dream Days – that earned him a place among the bohemian literary set of his day. It’s the stories he spun for his fragile son, though, that ensured his lasting renown. When the BBC did a survey of the greatest books in English a few years ago, Grahame’s book came in at number sixteen. There’s a terrific sadness that ran through Grahame’s life, some of it by chance, some of it of his own making, but I suspect he would have found some true satisfaction that, over a century after its first publication, The Wind in the Willows still brings enormous joy to readers of all ages.

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.